Shinran (親鸞) | |

|---|---|

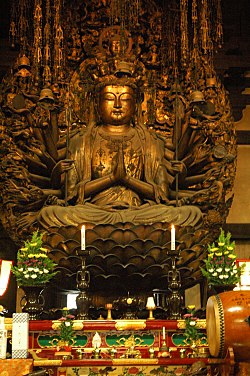

Shinran (ICP) (Nara National Museum) | |

| Title | Founder of Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism |

| Personal life | |

| Born | Matsuwakamaro May 21, 1173 |

| Died | January 16, 1263 (aged 89) Heian-kyō, Yamashiro Province |

| Spouse | Eshinni |

| Children | Kakushinnhi, Zenran, others |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Hōnen |

Shinran (親鸞; Japanese pronunciation: [ɕiꜜn.ɾaɴ],[1] May 21, 1173 – January 16, 1263)[2][3] was a key Japanese Buddhist figure of the Kamakura Period who is regarded as the founder of the Jōdo Shinshū school of Japanese Buddhism. A pupil of Hōnen, the founder of the Japanese Pure Land movement, Shinran articulated a distinctive Pure Land vision that emphasized faith and absolute reliance on Amida Buddha’s other-power.

While Shinran trained as a Tendai monk on Mount Hiei, he lived much of his life as a married Buddhist teacher unlike other Kamakura Buddhist reformers, and he described himself as "neither monk nor layman". Shinran's major work, the Kyōgyōshinshō (Teaching, Practice, Faith, and Realization), is a systematic exposition and defense of Pure Land doctrine. Shinran taught that liberation arises from the entrusting mind (shinjin) awakened through Amida's compassionate power, not from any merit or power of one's own. His interpretation profoundly reshaped the course of Japanese Buddhism and continues to influence East Asian religious thought.

Names

[edit]Shinran's birthname was Matsuwakamaro. In accordance with Japanese customs, he has also gone by other names, including Han'en, Shakkū and Zenshin, and then finally Shinran, which was derived by combining the names of Seshin (Vasubandhu in Japanese) and Donran (Tanluan's name in Japanese). His posthumous title was Kenshin Daishi.[4]

For a while, Shinran also went by the name Fujii Yoshizane.[5] After he was disrobed, he called himself Gutoku Shinran, in a self-deprecating manner. Gutoku means "Bald Fool", to denote his status as "neither a monk, nor a layperson".[6][7]

Biography

[edit]

Youth and monastic life

[edit]Shinran was born in Hino (now a part of Fushimi, Kyoto) on May 21, 1173, to Lord Hino Arinori (c. 1144-1181?) and Lady Arinori. Shinran was born to the Hino family, a lesser branch of the Fujiwara clan which had lost its rank after a scandal. The family was known for its scholars and had produced many generations of civil servants.[8]

Shinran's birth name was Matsuwakamaro. Early in Shinran's life his father died and so Shinran was educated by his uncle Hino Munenari. He was also cared for by his other uncle Hino Noritsuna. Some sources also indicate that Shinran's mother died when he was young, but these sources have not been verified.[9][10] Modern historians contest the identity and date of the death of Shinran's parents, with some suggesting he ordained alongside his father due to instability from the Genpei War.[11]

Influenced by the tumultuous events of the time such as epidemics and famines, many noble families turned to religious vocations during this era. Thus, Hino Arinori's children (Shinran's brothers) all eventually entered monasticism. Shinran himself was ordained as a monk in 1181 under the Tendai prelate Jien (1155–1225) when he was nine years old.[9] He received the Buddhist name Han'en.[9] Traditional sources state that Shinran had a wish to enter the monkhood himself, influenced by the death of his parents or by his mother's dying wish.[10]

Shinran lived as a monk on Enryakuji, Mount Hiei, for the next 20 years of his life (1181–1201). Letters between his wife and daughter indicate that Shinran's status was that of a modest dōsō (堂僧; "hall monk").[12][13] As a monk assigned to the jōgyōdō (walking samadhi hall), Shinran would have specialized in Buddhist liturgy and plainsong centered on Amida Buddha, which included a practice then known as “uninterrupted nembutsu” (fudan-nembutsu) and daily ritual recitation of the Amitābha Sūtra.[14] This experience likely influenced his love for Buddhist hymns.[14] Aside from this, historians also note that Shinran was part of the Tendai lineage of Genshin (the Ryōgon-Yokawa).[10] Thus, according to Jérôme Ducor, it is likely that Shinran practiced Genshin's Pure Land methods as taught in his Ōjōyōshū.[14] Apart from this, little is known of Shinran's life on Mt. Hiei. There are many hagiographical accounts of this period which exalt Shinran's status but little of this has been historically verified.[10]

Disciple of Hōnen

[edit]

At a certain point in his career, Shinran became dissatisfied with his spiritual life. According to various accounts, Shinran was frustrated with his own spiritual failures and feared being unable to attain enlightenment.[10] As such, he decided to go on retreat at Rokkaku-dō temple in 1201.[15] There, while engaged in intense practice, he experienced a vision of Avalokiteśvara appearing as Prince Shōtoku, directing Shinran to the Pure Land teacher Hōnen (who was now 69, and at the height of his popularity).[16][15]

In 1201, Shinran met Hōnen at his hermitage of Yoshimizu, near the capital Kyōto and quickly became his disciple, receiving a new name, "Shakkū" (綽空).[17][10] During his first year under Hōnen's guidance, Shinran abandoned the traditional Tendai Pure Land practices (though he remained a Tendai monk for now) and adopted Hōnen's teaching which focused solely on reciting the nembutsu, joining his new growing movement (Jōdoshū).[17] He remarks on this event in his Kyōgyōshinshō, where he simply writes: "But I, Gutoku Shinran, in the year 1201, abandoned the difficult practices and took refuge in the Original Vow."[10]

Shinran's precise status amongst Hōnen's followers is unclear as in the Seven Article Pledge, signed by Hōnen's followers in 1204, Shinran's signature appears near the middle, among less-intimate disciples.[18] According to Ducor, it is possible that during the half-dozen years he studied with Hōnen, Shinran lodged with some of his fellow disciples in the capital.[17] Also during this time, Shinran worked to copy and collate the works of the Pure Land tradition of Shandao.[19] Furthermore, though the two only knew each other for a few years, Hōnen entrusted Shinran with a copy of his Senchakushū in 1205 and allowed him to copy it, along with a portrait of Hōnen.[19] This privilege was only granted to a few of Hōnen's disciples and had great significance, amounting to a master's recognition of a disciple as a spiritual heir. Hōnen also gave Shinran a new name at this time, Zenshin.[19]

During his time in Kyōto, Shinran may have also gotten married (possibly between 1203 and 1207), giving back his monastic vows of celibacy.[20] The details of this marriage is the subject of much debate and discussion, with some scholars questioning whether the marriage occurred at this time or after Shinran's exile.[10] According to traditional sources, both Shinran and his wife are said to have had spiritual dreams foretelling of their future marriage.[21] Shinran's wife became known as Eshinni (惠信尼, 1182-1268?). She was a daughter of a civil servant appointed by the key Hōnen supporter Fujiwara no Kanezane, and likely a follower of Hōnen herself. Since her name contains the same character that Shinran's does, it is likely that she received this name on being married to Shinran. According to Ducor, this suggests that the marriage was endorsed by Hōnen.[21] Whenever the marriage occurred, it significantly changed Shinran's status to that of a shami, an ordained cleric who retained the external appearance of a monastic while not following all traditional monastic rules.[21]

Shinran may also have had another wife named Tamahi, a daughter of Kujo Kanezane, who stayed in Kyōto after his exile. Tamahi may have been Shinran's first marriage according to scholars like Michael Conway.[22]

Life in the provinces

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Japanese Buddhism |

|---|

|

In 1207, retired emperor Go-Toba issued a ban of Hōnen's nembutsu community. This ban followed an incident where two of Hōnen's followers aided the conversion of two noble court ladies, and were then accused of instigating sexual liaisons with them.[23][24] These two monks were subsequently executed. Hōnen and seven of his disciples, including Shinran, were all defrocked and exiled to different provinces. Shinran was sent to Echigo for five years.[24][25] Master and disciple would never meet again. Hōnen would die later in Kyōto in 1212.[2] In spite of this, Shinran saw the exile as an opportunity to spread the teachings, writing "If I did not go into exile, how would the beings in the remote places be saved?".[10]

While in exile, Shinran and his wife Eshinni received a ration of rice and salt that lasted one year. Furthermore, his uncle had previously been appointed as vice-prefect of Echigo. Eshinni's father had also been prefect in that province, and her family owned land there. Thus, the couple had connections in Echigo that provided some reprieve during the exile.[26] While in Echigo, the couple also had at least six children, three boys and three girls.[26]

Five years after being exiled in Echigo, in 1211, Shinran and all the exiles were granted amnesty and Hōnen returned to Kyōto. However, Shinran chose not to return to Kyoto at that time, staying two more years in Echigo.[27] Afterwards, Shinran left for the province of Hitachi, a small area in Kantō just north of modern Tōkyō. Shinran was likely following Hōnen's wishes, who had asked his disciples not to all meet up after his death, fearing succession disputes. He also may have wished to be closer to the new booming capital at Kamakura.[28]

During his move, Shinran began an extensive recitation of the three Pure Land sutras, seeking to recite them over a thousand times.[28] However, after a few days of this practice, he began to question the value of this effort. He would later write that during this time he thought the following:

If I am convinced that the true tribute to the benevolence of the Buddha is to have faith myself and to teach others to have faith, what do I lack beside his name so that I must absolutely read the sūtras? Having thought in this way, I stopped reading them.[28]

This was a significant turn in Shinran's religious life, and from now on he would focus exclusively on faith in the nembutsu as well as on spreading the Pure Land teachings, abandoning other more complex and difficult Buddhist practices.[29] It was also after this event that he adopted the name Shinran as well as Gutoku (愚禿; "Bald Fool"), coming to understand himself as "neither monk nor layman", but as a figure that transcends such distinctions while maintaining elements of both (e.g. marriage and the monk's robes).[29]

For twenty years, Shinran remained in the Kantō region preaching the Pure Land teachings. He mostly lived in the village of Inada (now Hitachi, Ibaraki prefecture) during this time, attracting many followers from all social ranks, especially lower classes like farmers, fishermen and warriors.[10] He did not establish a temple or an official sect of Buddhism. Instead, Shinran's followers met, studied with him, and then returned to their communities, creating informal groups called montos. These groups met in dōjōs, usually small buildings, often in private residences turned into chapels. They met on the 25th of each month, recited the nembutsu and listened to sermons or sutras. They used vertical scrolls with the nembutsu as their main object of worship. Often the calligraphy on these scrolls would be from Shinran himself.[29] Shinran kept in touch with his followers through letters, many of which survive.[29] Around eighty major disciples are known from the sources. Some of the most important communities include those of Shimbutsu (1209–1258), of his son-in-law Kenchi (1226–1310) in Takada, the congregation founded by Shōshin (1187- 1275) in Yokosone, and Shinkai's in Kashima.[29]

Retirement in Kyōto

[edit]In the 1230s (possibly 1234), Shinran left the Kantō area and returned to Kyōto, with his wife and children. There, he met with his fellow disciples, like Seikaku, author of Notes on Faith Alone, and celebrated the 23rd anniversary of Hōnen's death by holding a memorial where Shandao's Hymns in Praise of Birth in the Pure Land were recited.[30] Now in his sixties, Shinran considered that his preaching in Kantō had been successful, and felt he could retire to his hometown and see his other family members again.[30] Shinran's wife later retired to her family lands in Echigo with four of the children, while Shinran remained in Kyōto with his eldest son Zenran (善鸞 1217?–1286?) and his daughter Kakushinni.[30] He lived a frugal life in Kyōto, and had no fixed abode, staying at different places, including Zempōin, a Tendai temple headed by his brother Jin'u. He lived off donations from his Kanto congregations which at least allowed him to continue studying, writing and copying documents.[10][31] During this time, Shinran also raised and educated his grandson Nyoshin (1235–1300), son of Zenran.[31]

Shinran was a prolific writer, working well into his eighties. In 1234 Shinran published his magnum opus, the Kyōgyōshinshō, which is an anthology of Buddhist texts punctuated with Shinran's own commentary explaining and defending his understanding of the Pure Land teaching.[31] The work defends Hōnen's teaching from key critics, such as Myōe, and critiques the idealistic interpretations of Pure Land Buddhism influenced by figures like Shunjō. The work also contains the Poem of True Faith’s Nembutsu (Shōshin-nembutsu-ge), which is an original composition by Shinran that summarizes the Pure Land teaching.[32] Scholars debate the exact date for the composition of the Kyōgyōshinshō, the first draft of which may have been finished as early as 1224.[10]

While the Kyōgyōshinshō was written in literary Chinese, Shinran also worked to provide literature to his followers in vernacular Japanese. To this end, he copied works from fellow disciples of Hōnen, such as Seikaku's Notes on Faith Alone as well as Ryūkan's Jiriki-tariki-no-koto and Ichinen-tannen-fumbetsu-no-koto. Shinran also wrote commentaries to these texts, the Yuishinshō-mon’i and the Ichinen-tannen-mon’i.[10]

Shinran also composed five hundred and fifty Japanese didactic poems (wasan).[33] He further composed other short treatises in Chinese, other Japanese explanations of key passages, and numerous letters to his disciples addressing their questions, of which forty three survive.[10][33] Finally, Shinran also produced a compilation of the works of Hōnen along with other documents related to him. This compilation is the Compass for the Pure Land in the West (Saihō shinanshō).[33] Apart from this literary output, Shinran also spent much time giving oral teachings. Some of this is preserved in the Tannishō.[33]

After some time in Kyōto, Shinran had sent his son Zenran to supervise the communities in the Kantō region. However, he soon discovered that his son was abusing his status, accusing other disciples of heresy, distorting the teachings by telling people that he had received secret teachings from Shinran, conspiring to assume control of the Kanto congregations, and otherwise sowing discord among the community.[16][10] Shinran wrote stern letters to Zenran instructing him to change his ways (which included even insulting his own mother), but after Zenran's refusal, Shinran sorrowfully and publicly disowned him, writing to him that "from now on there shall no longer exist parental relations with you; I cease to consider you my son".[34]

Death and posthumous events

[edit]

Shinran died in Zempōin temple on 1263 at the age of 90 surrounded by some family and followers.[2][35] He died facing West, but no special preparation was taken before and during Shinran's death. This was against Japanese custom at the time, which took great care to prepare the dying person to attain birth in the Pure Land through numerous ritual means. Shinran rejected such rites as useless, believing that birth in the Pure Land was ensured by faith alone.[36] As such, Shinran made no requests for funerary rites, and merely asked that his body be tossed into the river to feed the fish. Nevertheless, he was cremated by his followers and his ashes were placed in Ōtani, not far from Hōnen's own tomb.[37]

Apart from recommendations to individual groups in his various letters, Shinran left no instructions on a direct successor for leadership of his community or for the founding of a new school or temple.[38] He also made it clear that he was not establishing a new master-disciple lineage (in the style of other schools like Tendai and Shingon). Indeed, Shinran explicitly writes about this issue:

As for me Shinran, I don't even have a single disciple. Here is why. If I made people say the nembutsu through my personal calculation, it would make them my disciples. But it would be completely foolish to call ‘my disciples’ those who say the nembutsu from Amida’s Solicitations.[39]

This is why Shinran's followers called themselves "followers" (monto 門徒) as well as "School of the Followers" (Montoshū 門徒宗) collectively.[39]

In 1272, Shinran's remains were moved further west into lands inherited by Kakushinni. This is now the site of Sōtaiin temple. A chapel with a statue of Shinran was constructed on the site of the new tomb. Shinran's followers gathered at the site every year to commemorate his death, a week long ritual known as Hōonkō.[37]

Kakushinni bequeathed the land to a community of local followers. She and her son Kakue were instrumental in maintaining the family's mausoleum, and passing on Shinran's teachings in the Kyōto region. Their descendants became the hereditary caretakers of the mausoleum. In the 14th century, the mausoleum developed into a temple known as the Hongan-ji (Temple of the Original Vow), with Kakushinni's descendants becoming the hereditary Monshu, or abbots of this temple.[37] Kakunyo (1270–1351), Kakue's grandson, wrote the first biography of Shinran, and also copied several texts which contain Shinran's oral teachings which he received from Shinran's grandson Nyoshin.[37] Zonkaku, Kakunyo's son, later wrote the first commentary to the Kyōgyōshinshō.

While Shinran was one of Hōnen's disciples, he was mostly ignored by authors of other schools of Japanese Buddhism after his death. Shinran is not mentioned by numerous sources which discuss Hōnen's successors. For example, Shinran is not mentioned in Notes of my Foolish Considerations, where Shinran's own Tendai teacher Jien discusses Hōnen. He is also not mentioned in Shunshō's Illustrated Life of His Eminence Hōnen, nor in Origins of the Traditions of the Pure Land, by Gyōnen.[40] Thus, Shinran's status as a Buddhist master and founder was mostly ignored by other traditions for centuries after his death, even while Honganji temple was growing in power and influence. It was not until the 17th century that the sources of other traditions begin mentioning Shinran.[37]

Knowledge of Shinran in the Western world only really began after World War II. The first English translation of the Kyōgyōshinshō was completed by Yamamoto Kōshō (1898–1976) in 1958. This was followed by the translations of Inagaki Hisao (1929–2021). A full translation of all the major works of Shinran was completed by Ryūkoku University's Buddhist Text Translation Centre and published as The Collected Works of Shinran in 1997. This project also included translations of other classic Pure Land works by the Pure Land patriarchs. Ueda Yoshifumi (1904–1993), Nagao Gajin (1907–2005), Inagaki Hisao and Tokunaga Michio were the major figures and editors of this project.[41]

Timeline

[edit]- 1173: Shinran is born

- 1175: Hōnen founds the Jōdo-shū sect

- 1181: Shinran becomes a monk

- 1201: Shinran becomes a disciple of Hōnen and leaves Mt. Hiei

- 1207: The nembutsu ban and Shinran's exile

- 1211: Shinran is pardoned

- 1212: Hōnen passes away in Kyoto and Shinran goes to Kantō

- 1224(?): Shinran authors Kyogyoshinsho

- 1234(?): Shinran goes back to Kyoto

- 1256: Shinran disowns his son Zenran

- 1263: Shinran dies in Kyoto

Teaching

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Pure Land Buddhism |

|---|

|

Shinran considered himself a lifelong disciple of Hōnen and a defender of his Shandao influenced Pure Land teaching. This tradition promoted the faithful recitation of the nembutsu as the main practice leading to birth in Amitābha's Pure Land, and thusBuddhahood itself. As seen in the writings of Shinran's wife Eshinni, in spite of their separation in exile, Shinran saw himself as someone who would follow Hōnen everywhere in spirit.[42]

While Shinran's teachings and beliefs were generally consistent with those found in Hōnen's movement, he also had several unique explanations of Pure Land Buddhism which emphasized several original views. According to Ducor, Shinran's originality "lies in his own rediscovery of the teachings of Tanluan, a forerunner of Shandao, as well as his re-reading of the earlier tradition in the light of his personal experience".[43] While Shinran never presented himself as a founder of a new sect or a reformer, Shinran's original teachings led to his system being seen as a new school in its own right, which is called by a name Shinran coined, the "True Pure Land School" (Jōdo-Shinshū).[43]

Amitabha and the Pure Land

[edit]One of Shinran's original contributions is his explanation of the nature of Amida Buddha. Pure Land masters like Daochuo, Shandao and their successors had understood Amida and his pure land as a sambhoghakaya Buddha and land (also called a retribution body in East Asian Buddhism). This retribution body and land is a direct result of the Original Vow to establish a perfect buddhafield where all beings could be easily liberated made by Amida when he was bodhisattva Dharmākara eons ago.[44]

Shinran accepts this diachronic way of seeing Amitabha as the result of a long bodhisattva career, but he also adds another way to understand the nature of Amitabha. According to Shinran, Amida is also the direct compassionate manifestation of the ultimate reality, the formless and indescribable Dharmakāya. Shinran writes that from the inconceivable Dharmakāya "a form manifested itself, which revealed itself in that noble appearance called ‘Dharmakāya in skillful means’ (Jp: hōben hosshin), took the name of ‘Bhikṣu Dharmākara’ and produced his inconceivable great Vow with its promise."[45]

He likewise explains this nature of Amida as the direct manifestation of the ultimate as follows:

From the precious ocean of unique suchness a form manifested itself that took the name of Bodhisattva Dharmākara. With the production of his Unobstructed Vow as the seed, he became the Buddha Amida, and that is why he is named ‘Comer-from-suchness as body of retribution (hōjin nyorai)...This Comer-from-suchness [Tathāgata] is also described as ‘Dharmakāya in adapted means’ (hōben hosshin). The ‘adapted means’ (upāya) consist in manifesting a form and revealing his Name in order to make himself known to beings. It is the Buddha Amida. This Comer-from-suchness is light. This light is wisdom. Wisdom is the form of light. As wisdom has no form, he is called ‘Buddha Inconceivable-Light’.[45]

This dual view (diachronic and synchronic) of Amida is influenced by Tanluan, who quotes the Avatamsaka Sutra to defend a similar view.[14] Shinran held that the formless and the form aspects of the Dharmakaya, which correspond to wisdom and skillful means, are non-dual. Since the formless is incomprehensible, it manifests forms out of compassion in order to guide deluded beings, an activity which is free, spontaneous and natural, like play.[42][46] On birth in the Pure Land, beings can realize the ultimate Dharmakaya once they've attained true faith.[42]

Shinran's discussion of Amida and his Pure Land also tends to emphasize their non-duality, inconceivability and transcendence of time and space rather than the concrete physical features of the body and land. Yet it is precisely by appearing as the light of the Dharma-body of compassionate means that the Buddha can benefit others as the "Tathagata of unhindered light filling the ten quarters". This infinite light and life is a form that is paradoxically without form and thus identical with Suchness. Thus, Shinran writes "know, therefore, that Amida Buddha is light, and that light is the form taken by wisdom".[47]

This infinite light is truly beyond form and formlessness, existence and non-existence, and all other conceptions with which we could describe it.[48] In a similar vein, the true nature of the Pure Land is not a place that can be described in spatial or temporal terms, rather it is "the place where one overturns the delusion of ignorance and realizes the supreme enlightenment" (Notes on 'Essentials of Faith Alone').[49] Thus, while the provisional and conventional pure lands are described in terms of palaces, jewels, flowers and so forth, the ultimate Pure Land is inconceivable and "infinite, like space, vast and boundless" (quoting Vasubandhu).[50]

Nevertheless, since Infinite Light is active Buddha wisdom, the specific forms of Amida Buddha's body and his Pure Land compassionately appear to teach and nurture all deluded sentient beings who are unable to perceive ultimate reality directly. According to Shinran this is Amida's Dharmakaya as compassionate means, which "refers to manifesting a form, revealing a name (Namo-amida-butsu) and making itself known to sentient beings."[51] This is how Shinran's buddhology affirms classic Mahayana non-dualism at the level of ultimate truth while also promoting a path that relies on dualities at the level of relative truth (such as those between Buddha and sentient beings, and the Pure Land and this defiled world).[52] As such, Shinran presents a path that affirms the ultimate unity of non-dualism and dualism, which is based on the inconceivable wisdom and compassion of Buddhahood itself.[52]

Nembutsu and shinjin

[edit]

Like Shandao, Tanluan and Hōnen, Shinran emphasized the nembutsu (a classic praise of the Buddha Amida's name) as the central practice of Pure Land Buddhism. Shinran developed a unique understanding of the nembutsu through his study of masters like Tanluan.[53] For Shinran, the nembutsu is inseparable from true faith (Jp: shinjin 信心), also known as the settled mind (anjin 安心). Indeed, Shinran sees the core of the "true practice" of nembutsu as none other than faith or true entrusting. As Shandao had taught, true faith is twofold: (1) a recognition of our own deep faults and afflictions as ordinary beings who cannot attain awakening by ourselves; (2) a deep trust that the other-power (tariki) of the vows of Amida can lead us to the Pure Land.[53]

According to Shinran, this conviction is opposed to the belief in self-power or personal power (jiriki 自力) which must be abandoned. Shinran defined this attitude that we must let go of as "believing in myself, believing in my own will, striving through my own strength, and believing in my own various roots of goodness," as well as "believing in myself and thinking of being born beautifully in the Pure Land by amending the disorder of my physical, verbal, and mental acts by the will of my own calculations."[54]

Self-power here signifies all manifestations of a person's desires and will to bring themselves to enlightenment, including practicing the nembutsu wishing to gain personal merit from it. Any meritorious deed or act of purification that relies on one's own designs and capacities is an act of self-power to be abandoned.[55] Thus, if one feels the need to "make oneself worthy" of the Buddha's infinite compassion through ethical deeds, sincerity, acts of charity, and meditative attainment, then one is still in the hold of egoistic self-power and is not truly entrusting.[55] All such efforts must be abandoned according to Shinran. Likewise, any sense of "calculation" (Jp: hakarai) is to be let go of, since it is also identical to self-power. Calculation refers to any kind of deliberation, planning or design regarding our spiritual path, and any mental activity that seeks to determine the "right" way to make oneself deserving of the Original Vow.[55] It is only when a person comes to realize that all their self-powered efforts and virtues in the quest for enlightenment are futile and defiled that they become open to Amida's gift of shinjin.[56] True shinjin is thus the mind that absolutely entrusts itself to Amida Buddha while also being deeply aware of its own inadequate and defiled condition.[57]

For Shinran, this true faith is the only cause for birth in the Pure Land (and thus, for Buddhahood). Shinran also writes that the true faith also corresponds to the Mahayana bodhicitta, the wish to attain awakening for the sake of all beings.[58] Furthermore, Shinran also equates shinjin with buddha-nature, writing that "shinjin is none other than buddha-nature," since the very heart-mind that entrusts to itself to the vow of the Dharmakaya of compassionate means is pervaded by the Dharmakaya as suchness.[59][60] Indeed, Shinran sees shinjin as ultimate reality itself, writing of "the ocean of entrusting that is itself suchness or true reality" which completely transcends all dualities.[61]

Shinran sees this ultimate faith of shinjin as something that is not produced through our own efforts and deliberations. Instead of an act of will, true faith is something given to us by Amida Buddha through his vows, and ultimately, it is the very wisdom activity of Buddhahood. True faith is thus a gift of Amida's true heart, the core of his vows, the unhindered wisdom light freely granted to all beings.[62][63][64] Those who sincerely trust in this and say Amida's name find themselves connected or matched with the Buddha's wisdom, something which Tanluan compares to how a box and its lid fit together. This "matching" or "yoking" (sōō 相應, i.e. yoga) is the Buddha's ultimate intention which is mirrored in the hearts of the practitioner, and this is true shinjin.[62] Thus, it is through faith that the Buddha's wisdom is transferred directly to sentient beings. As Shinran writes in one of his hymns (wasans):[62]

Obtaining the nembutsu of wisdom,

Is the fulfillment of the power of Dharmākara’s Vow.

Without the wisdom of the heart of faith,

How would we realize nirvāṇa?

Shinran writes in the Kyōgyōshinshō that true faith is something bestowed by Amida, not something that arises from the believer's efforts and practices.[42][64] Thus, Shinran writes that "our attainment of shinjin arises from the heart and mind with which Amida Tathāgata selected the Vow," and that all true practice and shinjin are "fulfilled through Amida Tathāgata’s directing of virtue to beings from his pure Vow-mind."[65] Through this endowment by the Buddha, the true faith awakens in the “one thought-moment of shinjin” (shin no ichinen), and the recitation of the Buddha's name or nembutsu becomes an expression of gratitude for the Buddha, and an expression of the Buddha's mind itself, which has filled the devotee. Thus, shinjin is the essential element of Pure Land practice, without which one's practice is not the "true and real" nembutsu practice.[63] Indeed, the true practice (which relies on shinjin), as well as the attainment of Buddhahood itself, also both arise only from Amida's power expressed as shinjin, not from any personal achievement or effort. Shinran's view of universal salvation based completely and exclusively on Amida's power has been called the teaching of "absolute other-power".[64]

Yoshifumi Ueda notes that a key distinction in Shinran's writings is between those who have attained true shinjin and those who have not.[66] If one's faith is not settled and one still has doubts, Shinran states that one should "to begin with, say the nembutsu in aspiration for birth", exhorting us to "give yourselves up to Amida's entrusting with sincere mind," and to give up all "self-power calculation".[66] Furthermore, even if one does not yet accepted true shinjin from the Buddha, Shinran thinks that one should still try to practice nembutsu as a way of saying thanks to the Buddha for our future liberation. Thus, one should always sincerely say the nembutsu out of gratitude, thinking of the Buddha's compassion and how only through the Buddha's power can one be saved. When eventually shinjin arises through the inconceivable working of the Buddha's Name, true practice will effortlessly arise, and one will be assured of birth in the Pure Land where Buddhahood is certain.[67][42] Indeed, according to Shinran, the Buddha's Name is the "efficient cause" of birth in the Pure Land and liberation. This Name (myogo), though being ultimately transcendent, also manifests itself in the world in many different ways, such as recitation of the nembutsu, the Pure Land teachings, and our subjective experience of faith.[64]

This unique interpretation is key to how Shinran understands and interprets the Chinese of the 18th vow, which he reads as follows:

All sentient beings, as they hear the Name, realize even one thought-moment of shinjin and joy, which is directed to them from Amida's sincere mind; and aspiring to be born in that land, they then attain birth and dwell in the stage of non-retrogression.[65]

Here, this key sutra passage from the Larger Sutra is interpreted by Shinran to mean that nembutsu and shinjin is something given by the Buddha. Furthermore, the "one thought-moment" is understood not as a single instant of thought (as in the traditional interpretation) but as referring to the "mind that is single" (isshin, a term from Vasubanhu's Pure Land Treatise), which is the mind "completely untainted by the hindrance of doubt", i.e. the very Buddha mind of the Original Vow.[68]

Ducor writes that Shinran's teaching is "characterized by a complete surrender of the personal power of the practitioner to the Other Power of Buddha Amida's vows. All in all, this method results in the complete removal of the illusionary ego, which is indeed the heart of the Buddhist path."[69] Similarly, Ueda and Hirota write that, "For Shinran, genuine utterance of the Name and shinjin are not generated out of human will, but emerge together as manifestations of the Buddha's working."[70] This means that someone with shinjin will "hear" the nembutsu as the call of Amida. Instead of experiencing it as something they "do" or "say", someone with shinjin experiences the nembutsu as coming from Amida's active wisdom and compassion.[70]

Once this true faith-nembutsu is felt and received, the recitation of the name becomes nothing more than "a spontaneous, natural expression of gratitude" to the Buddha's benevolence. Instead of seeing the recitation of the Buddha's Name as a means to an end, or a kind of mantric accumulation, it is experienced as an expression of true faith and of Buddhahood itself. As such, according to Shinran, "true faith is necessarily accompanied by the name. The name is not necessarily accompanied by faith [transferred by] the power of the Vow."[69] This means the true nembutsu definitely arises from shinjin, but there are those who say the nembutsu without shinjin.[71] Furthermore, since true faith is not separate from the Buddha's mind and wisdom, Shinran writes that the afflictions of those with shinjin "become one in taste with the sea of wisdom".[72] While we still remain sentient beings with all our afflictions, these afflictions also become pervaded with the Buddha's wisdom and the working of the Original Vow, making our future Buddhahood certain.[72]

The natural non-practice practice

[edit]

Since true faith and nembutsu are gifts from Amida, the true practice (when it arises from shinjin) is not a traditional Buddhist practice in the sense of an instrumental act meant to generate merit and wisdom. Instead, it is a grateful and natural (jinen) response by the devotee to Amida's grace which "embodying all good acts and possessing all roots of virtue, is perfect and most rapid in bringing about birth."[71] As Shinran writes:

In everything we do, let us not have intelligent thoughts about birth in the Pure Land; but, with delight, let us always remember that Amida’s Benevolence is profound! Then, the nembutsu will also be said. This is natural (jinen). Our lack of calculations is what is meant by ‘natural’. It is a matter for the Other Power.[69]

This nembutsu is also called a “non-practice” (higyō) by Shinran:

The nembutsu is non-practice and non-good for the practitioner. As it is not practiced through personal calculation, it is qualified as ‘non-practice’. Since it is not a good deed done by personal calculation either, it is qualified as ‘non-good’. Because it is entirely a matter of Other Power and is cut off from self-power, it is non-practice and non-good for the practitioner.[69]

Shinran also calls it the practice of "not-directing virtue" since it does not require us to transfer our meager merits towards Buddhahood, rather, it only relies on us receiving the Buddha's power and merits.[73] The true Pure Land practice for Shinran is this natural nembutsu that relies on other-power only. The influence of this other-power nembutsu is not affected by the number of recitations or by any other factor like depth of mindulness or meditative absorption. As long as it relies on the other-power, a single wholehearted nembutsu recitation has the same effect as reciting it thousands of times. What matters is whether the devotee has true faith in Amida's vow, not the mechanics of practice.[58][73]

The term "natural" (jp: jinen, ch: ziran, 自然), lit. "to be like this (nen), of oneself (ji)", is defined by Shinran as "uncalculated", an act that is done without any conceptualization or planning since it comes purely from the Buddha's power. This natural working is thus not something we "practice" or "do", but rather is received from the Buddha.[74][75] Furthermore, this natural entrusting-nembutsu also ultimately refers to "the way things are" or "suchness" (Tathātā), a classic Buddhist term referring to the ultimate reality, the Dharmakaya which is personified in Amida Buddha. Thus, the other-power nembutsu is a natural spontaneous activity that awakens us to the inconceivable ultimate reality, a reality which is always automatically working to save all beings.[76][75] Since "naturalness" is the active dimension of Buddhahood, it is also equated with the Fulfilled Pure Land and the Name of Amida itself.[77]

As Shinran writes:

Unsurpassable Buddhahood does not even have any form. Since it does not even have a form, we speak of ‘naturalness’ (jinen). When it manifests itself in a form, we no longer speak of ‘unsurpassable nirvāṇa’. It is to make us aware of this mode of absence even of form that we specifically speak of the ‘Buddha Amida’. That's what I learned. The Buddha Amida is to make us know the mode of naturalness. Once you become aware of this principle, there is no longer any need to constantly discuss this naturalness.(...) All this is the inconceivability of the wisdom of the Buddha (Shinran’s letter, Mattōshō 5).[76]

Shinran's doctrinal system

[edit]Shinran's doctrinal system is also unique in its layout of texts and hermeneutical structure. Unlike the other traditional Pure Land sects which rely equally on the “Three Sūtras and One Treatise”, which are the three Pure Land sutras plus Vasubandhu's Discourse on the Pure Land, Shinran singles out the Sutra of Immeasurable Life as the main Pure Land sutra and as the "consummation of the Mahayana" and as "the conclusive and ultimate exposition of the One Vehicle".[50] While he does not reject the other Pure Land sources, he sees them as provisional and secondary to the Immeasurable Life since it contains Amida's Original Vow (listed as the 18th vow), and promises to save all beings through Amida's power.[78][75] According to Dennis Hirota, Shinran sees the Sutra of Immeasurable Life as "the vehicle or means by which human beings are called to enter into engagement with the Buddhist path in a way that does not involve the self-assertion and self-affirmation that tend to taint endeavor in other paths of practice."[50] Furthermore, since the compassionate function of this vehicle is such that it embraces all sentient beings, good or evil, wise or deluded, it is the fulfillment of the Mahayana ideal to lead all beings to Buddhahood.[50]

Regarding the other Pure Land sutras, Shinran interprets these from two perspectives. From an explicit perspective, the Amitābha Sutra and the Contemplation Sutra are still linked to self-power practice (and correspond, respectively, to the 20th and 19th vows as well as to mediative nembutsu and vocal nembutsu).[78] However, implicitly, these sutras also communicate the true doctrine of faith in absolute other-power according to the 18th vow as found in the Sutra of Immeasurable Life.[78][75]

Regarding the Pure Land lineage that Shinran relies on, it differs from that outlined by Hōnen (Tanluan, Daochuo, Shandao, Huaigan, and Shaokang). Shinran instead outlines the following lineage: Nāgārjuna, Vasubandhu, Tanluan, Daochuo, Shandao, Genshin, and Hōnen.[79]

Shinran also outlined a unique doctrinal classification system which is now called "the four kinds in two pairs" (nisō shijū):[79]

- vertical exit (shushutsu 竪出): this refers to the gradual teachings of the path of sages, including Mahayana paths like Yogacara as well as Hinayana paths.

- vertical jump (shuchō 竪超): this refers to the sudden teachings of the path of sages, which includes Zen, and Esoteric Buddhist paths like Shingon and Tendai

- horizontal exit (ōshutsu 横出): these are gradual Pure Land teachings of the Pure Land, which rely on self-power and personal merit to gain birth

- horizontal jump (ōchō 横超): the sudden Pure Land teaching based on faith in Other Power, which refers to Shinran's teaching, the “True Pure Land School” (Jōdo-Shinshū)

The use of "vertical" and "horizontal" here refers to how the path of sages rely on the self-powered method of the bodhisattva path (even when it allows for skipping bodhisattva stages through sudden practice), while the Pure Land way focuses on liberating deluded sentient beings as they are through faith and the nembutsu.[80] The sudden Pure Land way, the Jōdo-Shinshū, is understood by Shinran in two main ways. Firstly, it is the true teaching of the Buddhas and is the ultimate reason for the Buddha's coming into our world. Since it is the most universal and accessible method for all beings at all times and places, it is also the final intent of the One Vehicle.[80][58] Furthermore, the True Pure Land way is also the true teaching of Pure Land Buddhism based on the 18th vow and on other-power, as opposed to the provisional Pure Land teachings based on the 19th and 20th vows. Shinran also considered this to be the true teaching of Hōnen, which was passed on by himself and other disciples like Seikaku and Ryūkan, as opposed to other divergent interpretations taught by other disciples of Hōnen.[80]

The Path to the Pure Land

[edit]In several passages, Shinran also presents a unique view of the path he took in accepting the True Pure Land way and this became a schema for understanding the Pure Land path in his tradition. The three main stages of this Pure Land path, which can also be three different paths individuals can take, are as follows:[81][82]

- The provisional path of "birth through various practices". This refers to various Pure Land methods and practices that are either part of the path of sages (but whose merit has been dedicated to birth in the Pure Land) or that rely on self-power, such as those taught in the Tendai school and in the Contemplation Sutra. Shinran associates this path with Amida's 19th vow which speaks of "performing meritorious acts." Those who practice these believe that they must cultivate merit and wisdom to achieve Buddhahood. They also still doubt that the universality of the vow embraces everyone (and so believe they must practice hard to achieve birth). These people will likely be born in the "borderland".

- The provisional "true gate" practice of exclusive nembutsu which nevertheless still relies on self-power and sees the nembutsu as a way to accumulate personal merit. Shinran associates this self-power nembutsu with the 20th vow and the Amitabha Sutra, and states that those who practice like this, attempting to accumulate merit through extensive nembutsu recitation, will be born in the transformed land (nirmāṇa-kṣetra).

- The ultimate path is the true path of the universal vow, the no-practice practice of the nembutsu of true faith in Amida's other-power that has completely abandoned self-power. This is an expression of the 18th vow, and is associated with the Sutra of Immeasurable Life. Those who follow it will attain birth in the supreme Pure Land, the Truly Fulfilled Land.

According to Shinran, those who follow various Pure Land paths do not attain the same exact result. To explain this, Shinran also outlines different layers of the Pure Land:[58][83][84]

- The Borderland (辺地, henji, also called the realm of sloth and pride, the castle of doubt, or the womb palace) is on the border of the Pure Land. Those born there still have doubts about Amida, and so they do not see the Buddha for some time until they are purified of this. It is still a pure land from which one will not fall back into samsara, but it is not the true Transformed Land.

- The Transformed Land of Compassionate Means (方便化土, hōben kedo) are the nirmāṇakāya pure lands described in the sutras with features like the jeweled trees, ponds, etc. created by the power of Amida's vows. They are the lands which are perceivable by sentient beings and attained by the Pure Land paths that rely on self-power. Those who meditate on the Buddha Amitabha with faith, but have not fully abandoned self-power and have not attained shinjin will be born here, instantly attain the bodhisattva stage of non-retrogression, gain a divine body and other qualities.

- The Truly Fulfilled Land (真実報土, shinjitsu hōdo) is the eternal and uncreated Dharmakaya, i.e. Nirvana, the ultimate reality. According to Shinran, those with shinjin attain this land, which is Buddhahood itself, instantly after death, thus bypassing all the bodhisattva stages.

While Shinran outlines these two provisional lands and paths respectively, he also writes that all of them are skillful manifestations of the Original Vow meant to lead beings to true entrusting. As such, he does not reject the efficacy and importance of these provisional means, even while exalting the path of the 18th vow and the Fulfilled land as true and superior.[82] Indeed, Shinran understands the provisional paths as part of a process he himself undertook he calls "turning through the three vows" in which he first practiced in accord with the 19th vow, then the 20th and finally the 18th.[82]

Fruits of the Pure Land path

[edit]Pure Land masters had taught that the nembutsu held all the merits of Buddha Amida, which would be transferred to those who recited it. Like wearing someone's perfumed cloak and becoming perfumed, the recitation of the name of Amida infuses one with the merits of the Buddha. This is possible through the power of the Buddha's vow which "transfers" the infinite merits of the Buddha to the reciter. This doctrine of merit transference (ekō 廻向, pariṇāmanā) is key to Shinran's understanding of the nembutsu's working, which sees the nembutsu as containing within it the Buddha's power. As such, for Shinran, the results and effectiveness of the Pure Land way is not based on our own efforts and merits (self-power), but only on the Original Vow of the Buddha Amida (other-power).[63][53]

Shinran had a unique interpretation of shinjin's effect in this life. According to the Pure Land tradition of Shandao, birth in the Pure Land leads to the state of irreversibility or non-retrogression (Jp.: futaiten 不退轉, Skt.: avaivartika), a stage at which cannot fall back on the path to Buddhahood but only moves forward.[85] Shinran held that the stage of non-retrogression could be achieved in this life by any Pure Land devotee who has attained the true "revolution of the heart" (eshin, i.e. shinjin) that entrusts itself to the original vow of Amida and completely abandons self-power:

When foolish beings possessed of the afflictions, the multitudes caught in birth-and-death and defiled by evil karma, realize the mind and practice that Amida directs to them for their going forth [i.e. shinjin and nembutsu], they immediately join the truly settled of the Mahayana (Kyōgyōshinshō, ch. 4).[86]

This is attained in a single moment of faith, the “one thought-moment of shinjin”, which is really the reception of Amida's vow in a timeless event that is "time at its ultimate limit" according to Shinran. In this timeless instant of shinjin, our limited and conditioned life fuses with the limitless and eternal, the ocean of the Buddha's Vow, and enters the "stage of the definitely settled" [on the path to Buddhahood]. This attainment is unchanging, and is expressed through the nembutsu.[87] The attainment of shinjin also contains a recognition of the realm of nirvana, which "fills the hearts and minds of all beings". This nirvanic reality is "where one overturns the delusion of ignorance", and is none other than the buddha-nature which pervades samsara itself. Thus, according to Shinran, "the heart of the person of shinjin already and always resides in the Pure Land", even while still living in samsara.[88] Shinran also held that birth in the Pure Land leads immediately to Buddhahood for those with true faith.[85] Thus, to enter the true Pure Land is to realize enlightenment.[89] This is in contrast to other Pure Land views which held the Pure Land is a kind of bodhisattva training ground in which one must then practice the path for eons to attain Buddhahood.[85] According to Shinran,

Even if they have neither the practice of discipline nor the knowledge of wisdom, those who embark on the ship of Amida's vow do cross the sea of suffering of the cycle of births and deaths. As they reach the shore of the Pure Land of retribution, the black clouds of passions quickly dissipate, and the moon of the Awakening of the Dharmakaya appears immediately; and, sharing the same flavor as the unobstructed light filling the Ten Directions, they benefit all beings: then, at that moment, is the Awakening. (Tannishō, ch. 15) [90]

Apart from these major benefits of practicing the Pure Land way, Shinran also discusses the condition of the nembutsu devotee in this life. Since they have attained irreversibility, this means that they have also realized the attainment of "one more birth" (until the attainment of Buddhahood), which means they are equal in status to Maitreya and even "on an equal footing with a Tathāgata".[91] However, Shinran does not affirm the view that it is possible to "become a Buddha in this very life" (sokushin jōbutsu), an attainment which was widely promoted and taught in other Japanese schools of Buddhism like Shingon and Tendai at the time.[91] Shinran is explicit in the view that Buddhahood is only attained after we are born in the Pure Land, writing: "I have learned that, according to the true doctrine of the Pure Land, we have faith in the Primal Vow during this present life and we will open to awakening (satori) in that [Pure] Land."[91] Thus, our equality with a Buddha is only truly actualized in the Pure Land according to Shinran:

Sullied beings cannot see their own nature here, because it is covered by passions....But when they reach the Buddha Realm ‘Peaceful-Happiness’, their buddha-nature will necessarily immediately be revealed, as it will be based on the transfer of the Primal Vow’s power (Kyōgyōshinshō, ch. 5, § 37).[91]

This does not mean however that there are not other major benefits achieved in this life by nembutsu devotees. These are called the "Ten Benefits in the Present Life" and are outlined by Shinran as follows:[92]

- one is protected by many invisible beings like devas and bodhisattvas;

- one is endowed by the supreme merits of the Amida;

- our evil is transformed into good;

- one is protected by all the Buddhas in this life;

- one is praised by all the Buddhas;

- one is constantly protected by the spiritual light of Amida Buddha;

- one's heart is filled with much joy

- one recognizes the Buddha's benevolence and seeks to repay it

- one always practices great compassion;

- one enters into the group of those fixed in the true (i.e. the stage of non-retrogression from Buddhahood)

Furthermore, in some intimate letters, Shinran also discusses the heart of the nembutsu devotee as dwelling in the Pure Land:

The venerable of Guangmingsi [Shandao] explains in his Hymns on the Pratyutpanna that for one with the heart of faith, his heart already resides constantly in the Pure Land. ‘Resides’ means that in the Pure Land, the heart of one who has the heart of faith resides constantly. This is to say that such a person is the same as Maitreya.[93]

This idea would be expanded upon by Shinran's successors, who called it "birth in the Pure Land without abandoning the body".[93]

Regarding the moment of death, Shinran rejected traditional deathbed rituals and the common idea that one's manner of death was tied to one's birth in the Pure Land, writing in one of his letters: "Personally, I attach no significance to the manner of one's death, good or bad."[94] Shinran held that only one's faith mattered at the time of death, not "right mindfulness" (shōnen). Neither ritual preparations and performances nor whether one died peacefully or violently affected one's birth in the Pure Land. As long as they had faith, the dying thoughts and state of mind of the dying person did not matter according to Shinran. As such, birth in the Pure Land would be achieved regardless of how a faithful person died and whether or not there were auspicious or inauspicious omens during the process.[94] Indeed, the effort to control and predict a person's rebirth at the moment of death was merely another expression of grasping at self-power.[94] Shinran's position was criticized by other Pure Land teachers of the day, such as Benchō, who argued that those who died a bad death without proper guidance, chanting, or the right signs would not attain birth.[94]

Transference and evil transformed into good

[edit]Another original teaching of Shinran is his view of how the Pure Land path works. The classic Pure Land view held that the path works through the transference of merit from Amida to the practitioner, which also eliminates his afflictions. Shinran's analysis of Pure Land soteriology closely relies on the classic Mahayana doctrine of merit transference. According to Shinran, the transference of merit has a dual aspect: the transfer of merits in the going forth direction (ōsō-ekō) refers to how a bodhisattva dedicates his merit to his own awakening, and the transfer of merits in the returning direction (gensō-ekō) refers to how they transfer their merits in order to save all sentient beings. Shinran focuses on how this process applies to the Buddha Amida. Thus, only through the transfer of the Buddha's vow power can one be born in the Pure Land, and only through that power can one also return to samsara to save others.[95] Indeed, according to Shinran, the true faith, practice and realization of the Pure Land path all derive from the Buddha's power:

The teaching, practice, faith, and realization of the true Doctrine (Shinshū 眞宗) are the benefits transferred by the great compassion of the Tathāgata. Therefore, whether it is the cause or the fruit, there is nothing that is not the accomplishment of the transfer of the pure heart of the Vow of the Tathāgata Amida. Since the cause is pure, the fruit is pure too (Kyōgyōshinshō, ch. 4, § 13).[96]

Thus, all the key elements of the Pure Land path, including shinjin and the nembutsu, are ultimately all expressions of the true sincere heart-mind of the Buddha, which is replete with inconceivable, and inexpressible wisdom and power.[97] As such, sincere faith ultimately becomes a manifestation of the power of Amida Buddha in the heart of the devotee, rather than a quality that needs to be created and cultivated.[97]

Furthermore, for Shinran, the idea of "merit transference" is ultimately a secondary element of Amida's activity, which is based on the relative distinction between good and evil. Indeed, those who focus on this "belief in faults and merit" (shin zaifuku) may still harbor doubts and so they are likely to attain birth in the "borderland" of the Pure Land.[98] Shinran argues that the true doctrine of the workings of the Pure Land way is really the "transformation of evil into good" (temmaku jōzen 轉悪成善) which for Shinran is prefigured in the Contemplation Sutra's statement that the Buddha's unobstructed light "fully illuminates the universes of the Ten Directions and embraces the beings of nembutsu without abandoning them."[98]

For Shinran, Amida's unobstructed light is none other than the perfection of wisdom that transcends the duality of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa, good and evil and transmutes all ignorance and afflictions into the two accumulations of merit and wisdom. As such, another way of understanding the effect of Amida's power is that it transforms our very afflictions into awakening. As Shinran says in a hymn:

From the benefits of Unobstructed Light [Amida],

We receive the magnificent and immense faith and

Necessarily, the ice of our passions melts

And immediately becomes the water of awakening.

The obstacles of our faults become the substance of His merits.

It is like ice and water: The more ice, the more water;

The more obstacles, the more merits.[99]

According to Shinran, this transformation of evil into good happens naturally, "without the practitioner having calculated it in any way" and without them having asked for it.[99] Shinran also explains that this transformation is often experienced as a sense of illumination in which one feels "accepted and protected by the unimpeded Light of Amida Buddha’s mind."[64] Bloom explains this as "that religious experience when the individual feels himself to be illumined, when the significance and meaning of the teaching becomes real to him."[64]

Ethics and evil

[edit]

Due to the unlimited compassion of Amida Buddha and his universal transformation of evil into good, the practice and attainment of Buddhahood in Shinran's Jōdo-Shinshū transcends good and evil. As Shinran states:[100]

Know that Amida's Primal Vow does not choose between young and old, or between good and bad, and that faith alone matters! The reason for this is that it is his Vow to relieve beings overwhelmed by evil from their faults and inflamed by their passions (Tannishō, ch. 1).

Shinran takes this teaching even further in his famous teaching of akunin shōki (惡人正機, lit. "evil people have the right capacity"):

Even a good person attains rebirth in the Pure Land, how much more so the evil person? But the people of the world constantly say, even the evil person attains rebirth, how much more so the good person. Although this appears to be sound at first glance, it goes against the intention of the [Original Vow] of Other Power. The reason is that since the person of self-power, being conscious of doing good, lacks the thought of entrusting himself completely to Other Power, he is not the focus of the [Original Vow] of Amida. But when he turns over self-power and entrusts himself to Other Power, he attains birth in the land of True Fulfillment…. Since its basic intention is to effect the enlightenment of such an evil one, the evil person who entrusts himself to Other Power is truly the one who attains birth in the Pure Land. Thus, even the good person attains birth, how much more so the evil person! (Tannishō, ch. 3) .[67]

In other words, since it is only through faith that one attains birth in the Pure Land, not through good deeds, keeping precepts, meditation etc., evil people (who understand their own state of affliction) are even more likely to achieve birth in the Pure Land than those who think themselves virtuous and rely on their own meritorious deeds.[100] This category of "evil persons" includes the worst types of beings, such as those who have committed the five grave offenses (such as harming a Buddha, killing their parents, etc.) and also icchantikas.[58] Indeed, the masses of evil people are the primary object of Amida's compassion according to Shinran, since those who consider themselves virtuous are less likely to believe they need Amida's help.[67]

Thus, no matter how evil a person may be, they will be liberated by Amida, and no matter how virtuous someone may be, they will not affect the Original Vow's activity in any way. The vow's infinite compassion is truly beyond good and evil and embraces all, therefore Shinran writes that he "knows nothing of what is good or evil", since he knows he is a foolish being that cannot know what the Buddha knows. Nevetheless, Shinran affirms the one thing he does know, "the nembutsu alone is true and real".[101]

This radical and universalist doctrine led some of Shinran's followers to promote certain heretical exceses however. One of the worst of these was the heretical view of "licensed evil" which taught that because one was definitely saved by Amida's power, one could (and even should) commit as many evil acts as one wished without concern, and that this actually aids Amida's compassionate response. Shinran explicitly rejected this, saying "just because the antidote exists does not mean you should prefer poison!".[10][102] He refuted this kind of antinomianism by relying on his teaching of shinjin, for if one deliberately committed evil as a means to incite Amida's compassion, one was also relying on egoic self-power and trying to cheat the Buddha's intent which is aligned with the good.[67] Shinran also taught his disciples to avoid such evil people and to be careful to whom they teach the doctrine of akunin shōki, lest they misunderstand it.[10]

Regarding the status of the Buddhist ethical precepts themselves, Shinran followed the view of Hōnen, who saw them as necessary for those on the path of sages, but not for those on the Pure Land path. Hōnen held that since the world had entered the Age of Dharma Decline, the path of sages that relies on accumulating merit and wisdom was no longer a workable path for most people, and thus, the precepts were obsolete.[103] This view is merely an extension of the argument made by the Tendai founder Saichō, who had meant it only to show the obsolence of the Hinayana Vinaya precepts. Shinran however, applied this to the Mahayana bodhisattva precepts as well. Thus, Shinran directly quotes Saichō in the Kyōgyōshinshō to show that during the Age of Dharma decline "there is no longer the element of the precepts". He also cites various Mahayana sutras which indicate that during the Age of Decline, monks will marry and have children.[103] Some of these sutras also indicate that during this age, there will be "monks in name only" who do not keep precepts but retain the tonsure and wear the robes. In the absence of true precept-keeping monks, it is these precept-less monks who will be valued by the community. Thus, Shinran presented himself as one of these monks of the Age of Decline who was “neither a monk nor a layman”, and yet still followed the Buddha's way.[103]

While Shinran's teaching has been seen as de-emphasizing morality and not requiring any ethical practice whatsoever, Shinran did state that the practice of the nembutsu can lead to a wish to abandon evil, writing: "In people who have long heard the Buddha's Name and said the nembutsu, surely there are signs of rejecting the evil of this world and signs of their desire to cast off evil in themselves."[104] Thus, through the power of the Buddha, evil people can come to abandon their evil thoughts.[105] As Shinran writes in a wasan hymn:[106]

When the waters—the minds, good and evil, of foolish beings—

Have returned to and entered the vast ocean

Of Amida's Vow of wisdom, they are immediately

Transformed into the mind of great compassion.

Shinran also writes that compassion and a wish to live in harmony with others can arise through faith, and thus "when we entrust ourselves to the Tathagata's Primal Vow, we, who are like bits of tile and pebbles, are turned into gold".[66] He also writes that in a person of faith there arises signs of "rejecting the three poisons", "gentleheartedness and forebearance".[107] Likewise, he writes:

When one has boarded the ship of the Vow of great compassion and sailed out on the vast ocean of light, the winds of perfect virtue blow softly and the waves of evil are transformed.[108]

However, this personal transformation is not a willed act nor an instant act of ethical perfection, but a natural and spontaneous process resulting from the influence of other-power which manifests in different ways according to the spiritual dispositions of each person. There is thus no singular set of ethical rules or moral injunctions in Shinran's teaching.[105]

Furthermore, there is no expectation of moral perfection in this life, and our assurance of future Buddhahood is held within our own corrupt and limited lives.[109][110] Indeed, the acceptance of one's own corrupt and defiled mind aids one's sense of faith in the Buddha's vow power, since this helps us realize that we can rely on no power but Amida's power.[110] As such, while the afflictions are said to be transformed into good, they are not completely eradicated in this lifetime, but are embraced and accepted in the very mind of shinjin which unites samsara and nirvana, delusion and enlightenment.[111] While the afflictions continue to arise until our birth in the Pure Land, they are accompanied by a deep self-reflection that knows their nature, and an all-embracing compassion.[112]

Thus, shinjin includes a realization of the deep ethical limitations of the self, of our need to abandon self-power, accept our delusions and afflictions, and rely on the Buddha which embraces us just as we are.[113][111] This means that true shinjin, in understanding that the self must be abandoned, includes an element of prajña (wisdom).[60] Shinran writes: "Know that since Amida's Vow is wisdom, the emergence of the mind of entrusting oneself to it is the arising of wisdom."[60] As Ueda and Hirota explain, this means that "Amida Buddha, as the embodiment of wisdom-compassion, becomes one with the karmic evil and blind passions of beings in order that they awaken to authentic self-knowledge, that is, be brought to realization of no-self and enlightenment."[114] Furthermore, Amida's virtue "is not simple goodness as opposed to evil" but instead embraces evil as it is. As such, one's karmic afflictions do not disappear in this life but become illuminated by wisdom and compassion and are made to fulfill Amida's working.[114]

Other religious paths and practices

[edit]Hōnen's disciples were divided on different questions, such as the emphasis on faith vs practice, and the emphasis on reciting Amida's name many times vs just a single time. Shinran, like Hōnen's disciple Kōsai, leaned more toward faith over practice, however he also rejected the single-recitation teaching which argued that one should just recite a single "Namo Amida Butsu" in one's life and avoid saying it again or risk grasping at self-power.[115]

While Shinran acknowledged the other Japanese religious practices outside the Buddhist tradition, including Shinto kami, spirits of the dead, divination, astrology, etc., he believed that they were irrelevant to Pure Land Buddhists.[42] He devotes several passages of Kyōgyōshinshō chapter six to criticizing such practices as divination and astrology along with the cult of numerous deities and kami. While he did not deny that deities existed and could protect people, he held that this was simply a benefit of nembutsu practice, since the deities serve the Buddha.[92] As such, Shinran writes "if one has taken refuge in the Buddha, one must not further take refuge in various gods".[116]

His followers would later use these critiques both to enforce proper interpretations of Shinran's thought and to criticize "heretical" practices and sects such as the Tachikawa-ryū and kami worship.[117] To this day, kami shrines, and the selling of omamori, ofuda and other charms are generally not found in Jōdo Shinshū temples, while these are common features of other Japanese Buddhist temples.

Comparisons to protestantism

[edit]Shinran's thought has often been compared to that of prostestant theologians like Martin Luther (1483–1546) and John Calvin (1509–1564), a view so widely repeated it has become a cliché. This began as early as the sixteenth century with a comparison made by the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606). Much later, Protestant theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968) would compare the two faiths in his Church Dogmatics (I, 2, § 17), mentioning their similarity in matters such as “grace,” “original sin, representative satisfaction, justification by faith alone, the gift of the Holy Ghost” and so on. However, according to Ducor, "this comparison only reveals superficial appearances", as was already discussed by the Jesuit Henri de Lubac in his monograph Amida.[118]

As de Lubac wrote, Amida Buddha is "not God in any sense", since Buddhism explicitly rejects theism. Furthermore, as Ducor explains, while the term "grace" may correspond to the notion of the transfer of merit or the transformative light of Amida, none of this is the same as the Christian “redemptive grace of forgiveness” which relies on the various Christian views on sin and on theories of justification, all ideas foreign to Buddhism.[118]

Cultural legacy

[edit]

A statue of Shinran Shonin stands in Upper West Side Manhattan, in New York City on Riverside Drive between 105th and 106th Streets, in front of the New York Buddhist Church. The statue depicts Shinran in a peasant hat and sandals, holding a wooden staff, as he peers down at the sidewalk. Although this kind of statue is very common and often found at Jōdo Shinshū temples, this particular statue is notable because it survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, standing a little more than a mile from ground zero. It was brought to New York in 1955. The plaque calls the statue "a testimonial to the atomic bomb devastation and a symbol of lasting hope for world peace."[119]

Shinran's life was the subject of the 1987 film Shinran: Path to Purity, directed by Rentarō Mikuni (in his directorial debut, based on his own novel)[120] and starring Junkyu Moriyama as Shinran. The film won the Jury Prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival.[121]

On March 14, 2008, what are assumed to be some of the ash remains of Shinran were found in a small wooden statue at the Jōrakuji temple in Shimogyō-ku, Kyōto. The temple was created by Zonkaku (1290–1373), the son of Kakunyo (1270–1351), one of Shinran's great-grandchildren. Records indicate that Zonkaku inherited the remains of Shinran from Kakunyo. The 24.2 cm wooden statue is identified as being from the middle of the Edo period. The remains were wrapped in paper.[122]

In March 2011, manga artist Takehiko Inoue created large ink paintings on twelve folding screens, displayed at the East Hongan Temple in Kyoto. The illustrations on the panels include Shinran and Hōnen leading a group of Heian era commoners on one set of screens and Shinran seated with a bird on the other set.[123] Author Hiroyuki Itsuki wrote a novel based on Shinran's life which was serialized with illustrations by Akira Yamaguchi and won the 64th Mainichi Publishing Culture Award Special Prize in 2010.[124]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Kindaichi, Haruhiko; Akinaga, Kazue, eds. (10 March 2025). 新明解日本語アクセント辞典 (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Sanseidō.

- ^ a b c Popular Buddhism in Japan: Shin Buddhist Religion & Culture by Esben Andreasen, pp. 13, 14, 15, 17. University of Hawaiʻi Press 1998, ISBN 0-8248-2028-2.

- ^ The Life and Works of Shinran Shonin.

- ^ "Shinran | Japanese Buddhist philosopher | Britannica".

- ^ Young Man Shinran: A Reappraisal of Shinran's Life. Takamichi Takshataka, Wilfrid Laurier Press, p. 2.

- ^ "Principle Teachings of the True Sect of Pure Land: I. His…". Sacred Texts. p. 9. Retrieved 2025-11-02.

- ^ Pratap, Mrigendra (2024). "The Emergence and Evolution of the "Neither Monk nor Layman" View in Shinran, Ambedkar, and Sangharakshita's Work" (PDF). Journal of World Buddhist Cultures. 7 (3): 32. Retrieved 2025-11-02.

- ^ Ducor, Jérôme: Shinran and Pure Land Buddhism, p. 25. Jodo Shinshu International Office, 2021 (ISBN 0999711822).

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Bloom, Alfred. “The Life of Shinran Shonin: The Journey to Self-Acceptance.” Numen, vol. 15, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–62. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3269618. Accessed 31 Oct. 2025.

- ^ Bloom, Alfred (2006). The Essential Shinran: A Buddhist Path of True Entrusting. World Wisdom. ISBN 978-1933316215.

- ^ Bloom, Alfred (1968). "The Life of Shinran Shonin: The Journey to Self-Acceptance" (PDF). Numen. 15 (1): 6. doi:10.1163/156852768x00011. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Ducor, 2021, p. 28.

- ^ a b Ducor, 2021, pp. 29-30.

- ^ a b "Shinran Shonin". www2.hongwanji.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2008-03-18. Retrieved 2025-06-12.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 30.

- ^ Dobbins, James C. (1989). Jōdo Shinshū: Shin Buddhism in Medieval Japan. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33186-2.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 31.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 33.

- ^ Rev. Yamada, Ken (2020-05-14). "The Shinran You Never Knew". Higashi Honganji USA. Retrieved 2025-11-09.

- ^ Bowring, Richard. Religious Traditions of Japan: 500-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. p. 247.

- ^ a b Ducor, 2021, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Shinran). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 807. ISBN 9780691157863.

- ^ a b Ducor, 2021, p. 34, 37.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, pp. 34-35.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e Ducor, 2021, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Ducor, 2021, p. 38.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, pp. 38-39.

- ^ a b c d Ducor, 2021, p. 39.

- ^ "Uncollected Letters, Collected Works of Shinran". Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 40.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, pp. 40-41.

- ^ a b c d e Ducor, 2021, p. 41.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, pp. 80-81

- ^ a b Ducor, 2021, p. 81.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 79.

- ^ Ducor, 2021, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f Dobbins, James C. (1989). "Chapter 2: Shinran and His Teachings". Jodo Shinshu: Shin Buddhism in Medieval Japan. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253331862.

- ^ a b Ducor 2021, p. 43

- ^ Ducor 2021, p. 46.

- ^ a b Ducor 2021, p. 47.

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, p. 56. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 56-58. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, p. 59. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, p. 60. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b c d Hirota, Dennis. "The Nature of Mahayana in Shinran" Hōrin: vergleichende Studien zur japanischen Kultur 20 (2019)

- ^ Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 173

- ^ a b Schmidt-Leukel, Perry (2024-04-01). "Non-dualism as the Foundation of Dualism: the Case of Shinran Shōnin". Journal of Dharma Studies. 7 (1): 27–39. doi:10.1007/s42240-023-00153-w. ISSN 2522-0934.

- ^ a b c Ducor 2021, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Ducor 2021, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Ueda & Hirota (1989), pp. 159-160

- ^ Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 161

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 46-47. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b c d e Inagaki, Hisao. Some Reflections on the Kyōgyōshinshō 2009

- ^ Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 175.

- ^ a b c Tanaka, Kenneth K. "The Dimension of Wisdom in Shinran's Shinjin: An Experiential Perspective within the Context of Shinshu Theology." Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. Vol. 63, No. 3, March 2015.

- ^ Ueda & Hirota (1989), pp. 167-168

- ^ a b c Ducor 2021, p. 51.

- ^ a b c S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 20-22. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom, Alfred, “Faith: Its Arising,” in Alfred Bloom, Shinran’s Gospel of Pure Grace, Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1965, pp. 45–59

- ^ a b S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 36-38. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b c Ueda, Yoshifumi (1985). How is Shinjin to be Realized? Pacific World Journal, New Series 1, 17–24. (Footnote p. 24)

- ^ a b c d Jones (2021), chapter 11, pp. 136-151

- ^ S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 38-40. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b c d Ducor 2021, p. 52.

- ^ a b Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 149

- ^ a b S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, p. 36. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 151

- ^ a b S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 30-31. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ Ducor 2021, p. 77.

- ^ a b c d S., Hirota, D. (1997). The Collected Works of Shinran: Introductions, Glossaries, and Reading Aids, pp. 27-29. Japan: Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-Ha.

- ^ a b Ducor 2021, p. 78.

- ^ Ueda & Hirota (1989), p. 177

- ^ a b c Ducor 2021, pp. 58-59.

- ^ a b Ducor 2021, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Ducor 2021, p. 60.