Western Marxism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory that emerged in Western and Central Europe following the failure of proletarian revolutions in the advanced capitalist world after World War I. The term denotes a loose collection of theorists who emphasized the philosophical and cultural aspects of Karl Marx's thought, in contrast to the more economistic and deterministic interpretations of orthodox Marxism and Marxism–Leninism. The movement's key early figures included Georg Lukács, Karl Korsch, and Antonio Gramsci. Later theorists associated with Western Marxism include the members of the Frankfurt School (such as Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Walter Benjamin), as well as Jean-Paul Sartre, Henri Lefebvre, Louis Althusser, and Jürgen Habermas.

The historical context of the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia and the crushing of revolutionary movements in countries like Germany, Hungary, and Italy between 1918 and 1923 led to a profound and lasting divorce between socialist theory and the working-class movement, a stark contrast to the unity of theory and practice that had defined the preceding tradition of classical Marxism. Western Marxism's major theorists were largely professional philosophers and academics rather than political leaders. This academic turn was accompanied by a shift in Marxist theory's geographical center of gravity from Eastern to Western Europe—primarily Germany, France, and Italy—and was further consolidated by the rise of Stalinism and fascism.

Western Marxism is characterized by a philosophical, rather than scientific, approach; a primary focus on culture and the "superstructure"; and a deep engagement with humanism and idealism, particularly the thought of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. The tradition also involved a preoccupation with epistemology and method; the development of an esoteric and complex language; a deep engagement with non-Marxist intellectual currents and a search for philosophical ancestries to Marxism in earlier Western thought; and a pervasive, though often latent, pessimism about the prospects for revolutionary change. The historian Martin Jay suggests that the central, contested concept that unites the otherwise disparate thinkers of the tradition is that of "totality", while J. G. Merquior argues that a defining feature of the tradition is its Kulturkritik, a romantic and humanist revulsion against industrial modernity that often conflated its critique of capitalism with a rejection of modern civilization itself.

Etymology and definition

[edit]The term "Western Marxism" is generally understood to denote non-Soviet Marxist thought, though its geographical meaning can be misleading, as not all Marxists in the West fall under its definition.[1] The movement's origins lie in the early 1920s as a theoretical challenge to the official Soviet interpretation of Marxism.[2] The first use of the term has been traced to the Communist International (Comintern)'s 1923 polemical attack on the work of Georg Lukács and Karl Korsch,[3] and by 1930, Korsch was using the term "western communists" to describe himself and others who opposed the Comintern.[4] The phrase is more generally attributed to Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who popularized it in his book Adventures of the Dialectic (1955).[5][6]

In his 1976 study, Considerations on Western Marxism, Perry Anderson defines Western Marxism primarily by its "structural divorce from political practice", which marked a radical break from the classical Marxist tradition of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Karl Kautsky, Vladimir Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, and Leon Trotsky, whose theoretical work was organically connected to their role as leaders or militants within working-class organizations.[7] For Anderson, Western Marxism represents a theoretical corpus produced during a long historical period of political defeat for the socialist movement in the advanced capitalist world.[8] This defeat, beginning with the failure of proletarian revolutions outside Russia between 1918 and 1923 and consolidated by the rise of Stalinism and fascism, severed the dynamic link between theory and mass struggle.[9] As a result, Marxist theory retreated from its classical concerns with economic laws and political strategy into the more abstract domains of philosophy, methodology, and culture, produced largely by academics "at an increasingly remote distance from the class whose fortunes it formally sought to serve or articulate".[10] The tradition's geographical axis also shifted, from the pre-1920 concentration in Eastern and Central Europe (Germany, Poland, Austria, Russia) to a new focus on Germany, France, and Italy.[11]

J. G. Merquior offers a complementary definition, highlighting three key characteristics: a prominent cultural focus, which he terms "the Marxism of the superstructure"; a staunchly humanist and idealist view of knowledge that rejects scientific determinism in favor of "critique"; and a broad eclecticism in its use of concepts from non-Marxist sources.[12]

Intellectual origins

[edit]Contrast with other Marxist tendencies

[edit]Anderson establishes the identity of Western Marxism by contrasting it with the "classical tradition" that preceded it. This earlier tradition, from Marx and Engels through the leading theorists of the Second International and the Bolshevik Revolution, was defined by several key characteristics:

- An organic unity of theory and practice, in which major theorists were also figures of political leadership in national parties.[13]

- A central focus on the economic laws of motion of capitalism and the political realities of the bourgeois state, with the aim of developing a strategy for proletarian revolution.[14]

- A vibrant internationalism, in which theorists from different countries engaged in extensive and passionate debate with one another.[15]

- A geographical center of gravity in Central and Eastern Europe.[16]

This tradition produced major works on economics (Luxemburg's The Accumulation of Capital, Rudolf Hilferding's Finance Capital, Nikolai Bukharin's Imperialism and World Economy) and developed a "Marxist science of politics" for the first time in the writings of Lenin and Trotsky.[17] Western Marxism, by contrast, arose from the perceived failures of this orthodox tradition, particularly its "fatalistic economism" and its inability to account for the resilience of capitalism and the defeat of the proletarian revolutions.[18] As Merquior notes, Western Marxism's philosophical challenge to deterministic historical materialism was not unique, having appeared in earlier Marxist "heresies" like Austro-Marxism (e.g., Max Adler, Hilferding) or the revisionist critiques of Eduard Bernstein and Georges Sorel. However, these earlier anti-determinist schools did not reject the ideal of Marxism as a science.[19] Western Marxism was defined from its inception by a rejection of Marxism as a science in favor of "critique"—a philosophical, rather than scientific, weapon.[20]

To further delineate the boundaries of Western Marxism, Anderson contrasts it with another intellectual tradition that also emerged from the struggles against Stalinism: Trotskyism. He presents the tradition of Leon Trotsky and his heirs (such as Isaac Deutscher, Roman Rosdolsky, and Ernest Mandel) as a "polar contrast" to Western Marxism.[21] Where Western Marxism was philosophical, academic, esoteric, and nationally confined, the Trotskyist tradition was political and economic, internationalist, written with clarity and urgency, and produced by persecuted exiles rather than university professors.[21] Most importantly, it sought to maintain the classical unity of theory and practice by engaging in the practical construction of revolutionary organizations, however small. While this defiance of the historical tide preserved the classical focus on economics and politics, it also came at a price, sometimes leading to a doctrinal conservatism and a "triumphalism" that asserted revolutionary prospects more by will than by intellect.[22]

The Hegelian and Engelsian schism

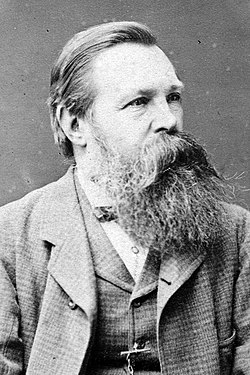

[edit]The historian Russell Jacoby argued that a crucial dividing line between Western and Soviet Marxism was a philosophical schism over their respective interpretations of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Engels. Jacoby identified two distinct Hegelian traditions that informed the two major schools of Marxism.[23]

- The "historical Hegelians", who would form the basis of Western Marxism, gravitated toward Hegel's early work, particularly the Phenomenology of Spirit. They emphasized the categories of history, subjectivity, and consciousness, and the idea of the subject attaining consciousness through the historical process.[23]

- The "scientific Hegelians", who became the progenitors of Soviet Marxism, valued Hegel as a comprehensive philosopher of a total system. They elevated the Science of Logic, the formality of the dialectic, and the "laws" of development, including the dialectic of nature.[23]

This division over Hegel was mirrored by a division over Friedrich Engels. Jacoby argues that Engels stood "firmly with a scientific Hegelian tradition", popularizing Marxism as a unified, objective system that encompassed both nature and history.[24] Orthodox Marxism, particularly in the Soviet tradition, leaned heavily on Engels to legitimate itself as a "science" of universal laws.[25] Western Marxism, by contrast, became defined by a critical re-examination of Engels and his relationship to Marx.[26]

The heresy of Lukács's History and Class Consciousness lay precisely in its challenge to Engels, arguing that the dialectical method was limited to the realms of history and society and could not be extended to nature, as this eliminated the "crucial determinants of dialectics—the interaction of subject and object".[25] According to Leszek Kołakowski, Lukács argued that extending the dialectic to nature rendered it a "contemplative bourgeois, reified sense" of ready-made laws, thereby stripping it of its revolutionary character as a theory of practice.[27] Jacoby argues that this critique of Engels did not begin with Lukács in 1923, but had originated with earlier Italian and French Marxists of the 1890s, such as Antonio Labriola, Georges Sorel, and Giovanni Gentile.[25]

Characteristics

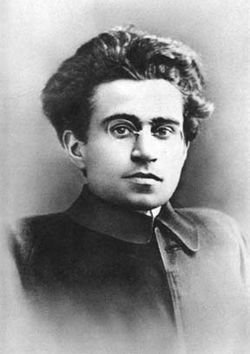

[edit]While early Western Marxists such as Lukács and Antonio Gramsci remained loyal to the communist movement and Leninism in their political practice, their theoretical work departed significantly from the orthodoxy of both the Second International and Soviet Marxism–Leninism.[28] Anderson identifies a set of interlocking formal traits that define the Western Marxist tradition as a coherent intellectual formation, despite the significant differences between its individual thinkers.

Divorce from political practice

[edit]The most fundamental characteristic of Western Marxism is the structural separation of its theory from the life of the working class. While the first generation—Lukács, Korsch, and Gramsci—were political leaders, their theoretical work was produced after their direct political involvement had been terminated by defeat.[7] Subsequent generations of Western Marxists were almost exclusively university-based academics.[29] This academic emplacement fostered an increasingly rarefied and specialized theoretical culture, marking a complete break with the classical tradition, where theorists taught at party schools and their work was directly tied to the strategic debates of the socialist movement.[29]

The official Communist Parties of the West became the "central or sole pole of relationship to organized socialist politics" for these thinkers, whether they joined, allied with, or rejected them. This relationship, however, was one of profound tension and distance, precluding any genuine synthesis of theory and mass practice.[30] The theorists of Western Marxism were often self-consciously an "intellectual avant-garde", proud of their intellectual status and with an "inorganic" relationship to the working class they claimed to represent.[31] The result was a "studied silence" in the core areas of classical Marxism: the economic analysis of capitalism and the political theory of the state and revolution.[32]

Shift to philosophy and methodology

[edit]The relinquishment of economic and political analysis was accompanied by a decisive "shift in the whole centre of gravity of European Marxism towards philosophy".[29] This was partly driven by the academic backgrounds of the theorists, who were overwhelmingly professional philosophers.[29] A powerful internal determinant for this shift was the belated publication in 1932 of Marx's Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, which revealed the Hegelian philosophical origins of his thought and provided a new focus for Marxist interpretation.[33] This philosophical turn led to a preoccupation with epistemology and method, producing a "prolonged and intricate Discourse on Method".[34] Works like Lukács's History and Class Consciousness (1923), Jean-Paul Sartre's Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), and Louis Althusser's Reading Capital (1965) are exemplary of this focus on uncovering the correct philosophical method for interpreting Marx and understanding society, rather than directly analyzing society itself.[34]

A further consequence of this shift was the development of an increasingly complex and esoteric language. Anderson argues that the "extreme difficulty of language" characteristic of much of Western Marxism was a sign of its divorce from a popular audience. This esotericism took varied forms: the "cumbersome and abstruse diction" of Lukács, the "painful and cryptic fragmentation" of Gramsci (imposed by prison), the "hermetic and unrelenting maze of neologisms" of Sartre, and the "sybilline rhetoric of elusion" of Althusser.[35] Martin Jay suggests that the very style of their writing, whose complexity defied popular comprehension, reflected a belief that defiance of the status quo could only be expressed in terms not easily absorbed and neutralized by popular discourse.[36]

Relationship with non-Marxist thought

[edit]In the absence of a dynamic relationship with a revolutionary working class, Western Marxism developed a new, intimate relationship with contemporary non-Marxist, and often idealist, systems of thought.[37] Anderson describes this as a "constant concourse with contemporary thought-systems outside historical materialism", which became a "specific and defining novelty of Western Marxism".[38] This led to a series of intellectual syntheses and confrontations:

- Lukács's work was deeply influenced by the sociology of Max Weber and Georg Simmel, the philosophy of Wilhelm Dilthey, and the neo-Kantian philosophy of Heinrich Rickert and Wilhelm Windelband.[39][40][41]

- Gramsci constructed his Prison Notebooks in a critical dialogue with the idealist philosophy of Benedetto Croce.[39][40][42]

- The Frankfurt School, particularly in the work of Herbert Marcuse and Theodor W. Adorno, integrated the concepts of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis into a Marxist framework, alongside influences from Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Nietzsche.[43][40][44]

- Sartre effected a synthesis between his own existentialism (itself derived from Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl) and Marxism.[43]

- Lucien Goldmann reduced Lukács's doctrines to a methodological system and combined them with the genetic epistemology of Jean Piaget.[45]

- Althusser drew upon the structuralist psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan and the philosophy of science of Gaston Bachelard.[43]

Parallel to this engagement with contemporary thought was a search for pre-Marxist philosophical ancestries. Whereas classical Marxists had generally seen Marx's work as a radical break, Western Marxists invariably sought to legitimize or re-interpret his thought by establishing a lineage from an earlier philosopher. This "compulsive return behind Marx" led to varied constructions of his intellectual descent: from Hegel (Lukács), Kant and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Lucio Colletti), Baruch Spinoza (Althusser), or even Niccolò Machiavelli (Gramsci).[46]

Centrality of "totality"

[edit]Martin Jay argues that the one major term that holds a special place in the lexicon of Western Marxism is "totality".[36] Jay contends that the intellectual preoccupation with the "whole" of reality is a distinct characteristic of "men of ideas", who combine the leisure to reflect on matters beyond immediate material concerns with the "hubris to believe they might know the whole of reality".[36] This totalizing impulse, which Lukács famously declared to be the very essence of Marx's method,[47] became the "God-term" of the discourse.[48] For Lukács, this concept was derived from Hegel's theory of the "concrete concept", wherein the part can only be understood in relation to the whole. From this standpoint, he argued that empiricism was the "ideological foundation of revisionism", as its focus on isolated facts prevented a grasp of the revolutionary transformation of society as a whole.[49] For Jay, the concept of totality is the "compass" that allows one to traverse the uncharted intellectual territory of Western Marxism.[50] However, while all Western Marxists were drawn to the concept, they were by no means unified in their understanding of its meaning or in their evaluation of its merits. Indeed, Jay suggests that the "major subterranean quarrel" of the tradition was waged over this concept's implications, a quarrel that produced the very different versions of Marxism associated with Lukács, Gramsci, the Frankfurt School, Sartre, and Althusser.[50]

Focus on culture and art

[edit]The primary substantive field of study for Western Marxism was culture. Within culture, it was "Art that engaged the major intellectual energies and gifts of Western Marxism".[51] This resulted in a sophisticated body of work on aesthetics that far surpassed anything in the classical tradition. Anderson points to Lukács's extensive work on the European novel, Adorno's writings on music, Walter Benjamin's essays on Charles Baudelaire and mechanical reproduction, Goldmann's study of Jean Racine, Galvano Della Volpe's critique of taste, and Sartre's monumental work on Gustave Flaubert.[52] Gramsci stands as a partial exception: while he wrote on literature, his main concern was the broader institutional structure of culture and its role in maintaining political power.[53]

According to J. G. Merquior, the missing element that distinguishes Western Marxism from other anti-determinist schools of Marxism is Kulturkritik, or culture-critique.[54] For Merquior, Western Marxism was not just the "Marxism of the superstructure", but also a theory of culture crisis and a "passionate indictment of bourgeois civilization".[54] This current of thought, which Merquior traces back to German romanticism, displayed an ingrained revulsion against the secular, utilitarian, and democratic values of modern industrial society.[55] Lukács, in a later self-criticism of his early work History and Class Consciousness, described its philosophy as "romantic anti-capitalism". Merquior argues that this label applies to much of the tradition, which often "conflated serious objections to bourgeois society with a rejection of industrial civilization based on modern technology and an ever more complex division of labour."[54]

Jacoby similarly notes that while orthodox Marxism's critique of capitalism was "corroded by the endorsement of its achievements" and its embrace of industrial progress, the unorthodox Marxists who critiqued capitalist rationality itself often "did not sever all links to conservatism, romanticism, or utopianism", naming William Morris, Ernst Bloch, and the Frankfurt School as examples.[56] Kołakowski concurs in his analysis of the Frankfurt School, describing their critique of "enlightenment" as a "fanciful, unhistorical hybrid" that attacked not only capitalism but also "positivism, logic, deductive and empirical science... mass culture, liberalism, and Fascism" in a manner "essentially in line with the romantic tradition".[57] This deep-seated hostility to the features of modernity as such, and not just its capitalist forms, set Western Marxism apart from the classical tradition's more ambivalent and often positive assessment of capitalist development.[54]

Pessimism

[edit]Anderson argues that a "common and latent pessimism" is the "fundamental emblem" shared by all these thematic innovations.[58] Each theory, in its own way, represents a "diminution of hope and loss of certainty" compared to the confidence of classical Marxism. Gramsci's theory implied a long, arduous "war of position" with no clear outcome; the Frankfurt School questioned the very possibility of human mastery over nature; Marcuse concluded that the working class had been absorbed into capitalism; and both Althusser and Sartre posited that even after a revolution, humanity would remain subject to the opaque forces of ideology or scarcity.[59] This underlying pessimism reflected the tradition's origins in a half-century of political defeat.[60]

Historical development

[edit]Political precursors

[edit]According to Karl Korsch, the philosophical works that defined Western Marxism in 1923 were a "weak echo of the political and tactical disputes" that had preceded them.[4] The tradition's origins lay in the political alternatives to Leninism developed by revolutionaries in Western Europe, primarily in Germany and the Netherlands. These "left communists" challenged the universal applicability of the Russian revolutionary model to the more advanced capitalist countries of the West.[61]

The Polish-German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg was a key influence. Though assassinated in 1919 before the term "Western Marxism" was coined, her critique of Lenin's organizational model in 1904 and her critical analysis of the Russian Revolution in 1918 were foundational for the tradition.[62] She argued that in Western Europe, where the proletariat faced the deeply embedded ideological control of bourgeois culture, revolutionary organization could not be based on the "military ultracentralism" and "blind obedience" of the Leninist party, but must arise from the spontaneous struggle and self-education of the working class itself.[63] After her death, her successor Paul Levi became the leader of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and a central figure in the early opposition to the Comintern. Levi challenged the Comintern's attempts to impose Russian tactics on Western Europe, arguing that they ignored the different "cultural structure" of the West and the need to win over the masses through patient, "organic" work rather than "mechanical splits" and putsches.[64]

Another major source was the "Dutch School" of "left" communists, including Anton Pannekoek and Herman Gorter. They argued that in the West, the power of the bourgeoisie rested less on force and more on its "spiritual" or cultural hegemony over the working class.[65] The key task for revolutionaries was to combat this "intellectual dependence" and build the proletariat's own consciousness and spiritual autonomy. For Pannekoek, the proletarian organization was not merely a tool for seizing power but "something spiritual; it is the complete transformation of the proletarian character."[66] This emphasis on consciousness and subjectivity, and their rejection of the Leninist party in favor of council communism, became central tenets of the political current that preceded Western Marxism's philosophical turn.[67]

Founding philosophical works

[edit]The abstract philosophy of Western Marxism was a direct result of the political defeats suffered by these early revolutionaries. Lukács had served as Deputy People's Commissar for Culture in the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919; Korsch was Minister of Justice in the short-lived Communist-led government of Thuringia in 1923; and Gramsci was a founding leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI).[68] Their political activity was cut short by the failure of the European revolutions: Lukács was forced into political quietism and exile, Korsch was expelled from the German Communist Party, and Gramsci was imprisoned by Benito Mussolini's fascist regime.[69] Their theoretical work, produced in this context of defeat and isolation, laid the groundwork for a Marxism separated from political practice.[70]

Lukács's collection of essays, History and Class Consciousness (1923), became a foundational text for the movement. Subtitled "Studies in Marxist Dialectics", the book rejected Engels's concept of a dialectic of nature and Lenin's reflection theory of knowledge, seeking to "recapture the Hegelian dimension in the formation of Marx's thought".[71][72] Instead, it presented Marxism as a method rooted in Hegelian dialectics, with the "point of view of totality" as its essence.[73] Lukács's work was a product of the "crisis in bourgeois culture" of the early 20th century and was deeply influenced by thinkers like Georg Simmel, Max Weber, and the neo-Kantian philosophers of Heidelberg.[74] Lukács analyzed modern society through the concept of reification, an expansion of Marx's theory of commodity fetishism which described how human relationships and activities are transformed into thing-like objects under capitalism.[75][76] He argued that the proletariat, as the "subject-object of history", occupied a unique position from which it could achieve a true consciousness of the social totality and overcome reification through revolutionary praxis.[77] Merquior characterizes Lukács's philosophy of this period as "culture communism," a theory of revolution motivated by the desire to restore a lost cultural harmony and overcome the "transcendental homelessness" of the modern age.[78]

Published in the same year as Lukács's book, Karl Korsch's Marxism and Philosophy (1923) was another key text that sought to restore the Hegelian character of Marxism.[79] It argued that the orthodox Marxism of the Second International had become a rigid, positivistic science that had forgotten its own historical and philosophical roots.[80] Korsch's work was directly inspired by Lenin's 1922 call to "organise a systematic study of the Hegelian dialectic from a materialist standpoint."[81] Korsch contended that Marxist theory had undergone a historical "decline" into a purely "scientific" theory, detached from the practical struggles of the working class.[82] He saw Lenin's work on the state as a "restoration" of the revolutionary connection between theory and practice, and aimed to perform a similar restoration for the problem of ideology and philosophy.[82] Along with Lukács's work, Marxism and Philosophy was condemned at the Fifth Congress of the Comintern in 1924 by Grigory Zinoviev in a "crude, demagogic denunciation" that marked the beginning of the Soviet suppression of independent Marxist theory.[79] The denunciation by the Soviet philosopher Abram Deborin represented a clash between the "historical" Hegel of Lukács and the "scientific" Hegel favored by Soviet orthodoxy.[83]

Antonio Gramsci, whom Leszek Kołakowski called "probably the most original political writer among the post-Lenin generation of Communists", developed his Marxist thought during his imprisonment.[84] His voluminous Prison Notebooks, written between 1929 and 1935 but not published until after World War II, developed a "philosophy of praxis" that departed from economic determinism and "rehabilitated the subjective, creative side of Marxist thought".[85][86] Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which analyzes how the ruling class maintains its dominance not just through force (the state) but through the consent of the governed.[87] According to Gramsci, this consent is achieved by disseminating the ruling class's values and worldview through the institutions of civil society (such as schools, churches, and the media).[88] He argued that the failure of revolution in the West was due to the strength of this hegemonic system, which required a "war of position"—a protracted struggle to build a counter-hegemony—rather than the Leninist "war of movement" that had succeeded in Russia.[89][88] Unlike other Western Marxists, Gramsci's work was deeply rooted in concrete historical and political analysis, particularly of Italian history, and lacked the strong element of Kulturkritik that characterized the German-speaking tradition.[90]

The Frankfurt School

[edit]

The "critical theory" of the Frankfurt School became the main idiom of Western Marxism after World War II.[91] Founded in 1924 through the efforts of Felix Weil, who had also organized the 1922 study group at Ilmenau where Korsch and Lukács first met, the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt shifted under the directorship of Max Horkheimer in the 1930s from empirical research on the German labor movement to a program of "social philosophy" and "cultural criticism".[92][93][94][10][95] The school tended to reject both the reformism of the Social Democrats and the "increasingly ossified doctrines of Moscow-orientated Communism", instead re-examining "the basis of Marxist thought, concentrating their attention above all on the cultural superstructure of bourgeois society."[96] Weil's founding memorandum for the Institute had stated its goal as achieving "knowledge and understanding of social life in its totality."[97] This first generation of the school included Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Walter Benjamin.

Deeply influenced by Lukács's theory of reification, the Frankfurt School developed a pessimistic critique of modern society.[98] Their exile to the United States following the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 has been cited as the cause of their retreat from politics, though Horkheimer's earlier work showed an explicitly political and "left" communist orientation. His essay "The Authoritarian State" (1940) appealed to the tradition of workers' councils and critiqued the Leninist party as a deadening bureaucratic structure.[99] In their seminal work Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), Horkheimer and Adorno argued that the Enlightenment's project of liberating humanity through reason had dialectically turned into its opposite: a new form of domination. They identified "the self-destruction of the Enlightenment" as their subject, asserting that a "fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant."[100] They saw instrumental reason, which seeks to control nature and humanity, as the underlying logic of both capitalism and fascism, culminating in the "culture industry" that manipulated mass consciousness and the administered world of "state capitalism".[101]

Walter Benjamin, an affiliate of the Institute, was a highly original literary critic and philosopher whose work combined German idealism, Jewish mysticism, and Marxism.[102] He developed concepts such as the "aura" to describe the unique presence of an original artwork, which he argued was decaying in the age of mechanical reproduction, opening up new possibilities for the politicization of art. His theory of allegory and his messianic critique of the idea of progress, articulated in the "Theses on the Philosophy of History" (1940), were deeply influential.[103]

Adorno's philosophy, particularly his Negative Dialectics (1966), rejected the Hegelian synthesis and the idea of identity between concept and object. He championed a "negative dialectic" that would remain true to the "non-identical" and resist conceptual closure, seeing modern art (particularly the music of Arnold Schoenberg) as a refuge for critical truth in a totally administered society.[104]

French developments

[edit]After World War II, France became a major center for Western Marxism. The strong position of the French Communist Party (PCF) in the post-war period created the conditions for a "generalization of Marxism as a theoretical currency in France" for the first time.[105] Before the war, Marxist theory had been relatively impoverished, with few translations of Marx's early works and little knowledge of Hegel.[106] An exception was the Surrealist movement, which in the 1920s developed an idiosyncratic concept of totality influenced by Hegel, Sigmund Freud, and a critique of bourgeois rationality.[107] Prominent post-war figures were Lucien Goldmann, Henri Lefebvre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre,[108] and Louis Althusser.[109]

Sartre, a leading figure in existentialism, sought to synthesize his philosophy with Marxism, a project he undertook in his massive, unfinished Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960). His existentialism protested against "the increasing tendencies of modern technology to treat men as things."[110] He declared Marxism "the unavoidable philosophy of our time" but rejected its deterministic elements.[111] Sartre's Marxism was a radical form of humanism that centered on the concept of praxis—purposive human activity. He contrasted the spontaneous, collective freedom of the revolutionary "group-in-fusion" with the alienated, serialized existence of individuals in the "practico-inert" field of established society. He distinguished between the dead, static "totality" of the practico-inert and the active, dynamic process of "totalization" that defined praxis.[112] His theory remained rooted in his existentialist ontology, prioritizing individual freedom ("project") over historical determination ("process").[113]

Arguments group

[edit]

In 1939, Henri Lefebvre, then a member of the French Communist Party (PCF), published a brief but revolutionary study of Marxist philosophy, Dialectical Materialism. In this work, he argued that the Marxist dialectic is based on the concepts of alienation and praxis, rather than the "Dialectics of Nature" found in Friedrich Engels's writings. Lefebvre drew heavily from the recently published 1844 Manuscripts, which he was the first to translate into French.[114]

However, it wasn’t until 1956, following the suppression of the Hungarian Uprising, that French Communist Party dissidents openly challenged the Marxist orthodoxy. This shift was marked by the creation of the journal Arguments, edited by Lefebvre, Edgar Morin, Jean Duvignaud, Kostas Axelos, and Pierre Fougeyrollas — all former or current members of the PCF. The journal became a focal point for a new Marxist humanist critique of Stalinism.[114]

The 1844 Manuscripts became a central reference for the journal, and existentialism had a significant influence on its approach. Lefebvre, for instance, looked to Sartre for a theory of alienation under capitalism. Lefebvre argued that alienation encompassed not only labor, but also consumerism, culture, systems of meaning, and language within capitalist society. Other members of the Arguments group were influenced by Martin Heidegger’s critique of Western metaphysics, viewing Marxism as flawed by its traditional metaphysical assumptions.[114]

Structural Marxism

[edit]

In the mid-1960s, Louis Althusser mounted a major challenge to humanist Marxism from a structuralist perspective. A philosopher for the PCF, Althusser argued for a scientific reading of Marx. In works like For Marx and Reading Capital (both 1965), he claimed that Marx's thought contained an "epistemological break" around 1845, separating his early "ideological" humanism from his later "scientific" materialism.[115][116] Althusser's "anti-humanism" redefined history as a "process without a subject", driven by the contradictions between forces and relations of production.[117] He distinguished between the "expressive totality" of Hegel, in which all parts are manifestations of a central essence, and the "decentered totality" of Marx, a complex structure of relatively autonomous levels that are "overdetermined" and ultimately determined by the economy only "in the last instance".[118] This stood in stark contrast to the PCF's official doctrine of socialist humanism, representing a development "against the grain of the political evolution of the PCF itself."[119] Althusser also developed a sophisticated theory of ideology, arguing that it functions through "Ideological State Apparatuses" (ISAs) like the school and the family to reproduce the relations of production.[120]

Italian developments

[edit]The "scientific" or Della Volpean school of Marxism emerged in Italy in the late 1950s as a critique of the humanist and historicist tradition of Gramsci.[121] Thinkers in this school sought to recover the "human, subjective dimension in the face of both the sclerosis of orthodox Marxism and the growing influence of technology," but were "radically opposed to that put forward by the Hegelo-existentialists."[122] Its founder, Galvano Della Volpe, rejected the Hegelian legacy in Marxism and sought to ground it in a rigorously scientific and materialist epistemology.[123] Influenced by David Hume, Immanuel Kant, and the logical positivists, Della Volpe argued for a "moral Galileanism" that would apply the methods of the natural sciences to the social world.[124] He developed a concept of totality based on what he called a "tauto-heterological" logic, which recognized both the identity and the difference between distinct elements, in contrast to the "pseudo-reconciliation" of Hegel's dialectic.[125]

His most prominent follower, Lucio Colletti, extended this critique to all of Hegelian Marxism. In works like Marxism and Hegel (1969), Colletti argued that the Hegelian tradition was fundamentally anti-scientific and idealist.[126] He identified a sharp opposition between the "bad infinity" of Hegel's dialectic, which absorbed all finitude into a speculative whole, and the materialist principle of "real opposition" found in Kant.[127] Colletti's critique extended to the Frankfurt School, whom he dismissed as reactionary "Luddites" for their critique of science, and even to Marx himself, whom he ultimately concluded was an inconsistent thinker who had failed to purge his work of its Hegelian, "dialectical" elements. This led to his abandonment of Marxism in the mid-1970s.[128]

Later theorists

[edit]

Ernst Bloch was a highly original thinker who sought to graft a "gnostic and apocalyptic style" onto Marxism, which he interpreted as a doctrine of utopian hope.[129] His magnum opus, The Principle of Hope (1954–59), explores the utopian impulse throughout history, from daydreams and fairy tales to architecture and religion. For Bloch, Marxism was the "concrete Utopia" that provided the scientific means to realize humanity's oldest dreams.[130] He argued for the continued relevance of religion, which he saw as preserving a "permanent indestructible root" that could be preserved in a "futuristic Marxism".[131]

Herbert Marcuse, another member of the original Frankfurt School, became one of the most influential Western Marxist thinkers in the 1960s, particularly among the New Left. In Eros and Civilization (1955), he synthesized Marx and Sigmund Freud, arguing that advanced industrial society enforced a "surplus-repression" of instinct that was no longer necessary for human survival. He envisioned a non-repressive civilization based on libidinal liberation.[132] His most famous work, One-Dimensional Man (1964), presented a bleak picture of a "totalitarian" consumer society that had absorbed all forms of opposition by satisfying material needs and manipulating consciousness.[133] Having concluded that the industrial working class was structurally "integrated" into the capitalist system and no longer a revolutionary force, Marcuse looked to marginalized groups—students, ethnic minorities, and intellectuals—as the new agents of radical change, advocating a "Great Refusal" of the existing order.[134]

Jürgen Habermas is the leading figure of the "second generation" of the Frankfurt School. Moving away from the pessimism of Adorno and Horkheimer, Habermas sought to ground critical theory on a new foundation.[135] In Knowledge and Human Interests (1968), he distinguished between different "knowledge-constitutive interests": the "technical" interest of the empirical sciences, the "practical" interest of the hermeneutic disciplines, and the "emancipatory" interest of critical theory.[136] His later work, culminating in the two-volume The Theory of Communicative Action (1981), developed a theory of "communicative rationality". Habermas argues that modern society has seen the "colonization of the lifeworld" (the sphere of symbolic interaction and shared understanding) by the "system" (the economy and the state), which operates on the logic of instrumental rationality.[137][138] He defends the "unfulfilled project of modernity" and posits an "ideal speech situation," free from domination, as the normative basis for a rational and democratic society.[139]

Critique and legacy

[edit]The legacy of Western Marxism has been a subject of extensive debate. In the late 1950s, Georg Lukács denounced much of Western Marxism, particularly the work of the Frankfurt School, for its pessimism and its distance from revolutionary politics. He characterized its proponents as dwelling in a "Grand Hotel Abyss", a "beautiful hotel, equipped with every comfort, on the edge of an abyss, of nothingness, of absurdity."[140] Russell Jacoby has countered that this critique ignores the political context of the period, arguing that the Frankfurt School's "pessimism" was a realistic response to the rise of fascism and Stalinism. He contrasts Lukács's "Grand Hotel Abyss" with the "Hotel Lux" in Moscow, a residence for foreign communists where many, including prominent figures who had opposed the early Western Marxists, were arrested and killed during Stalin's purges.[141]

Anderson concluded his 1974 essay by suggesting that the student and worker uprisings beginning with May 1968 in France heralded a new historical period. For the first time in fifty years, the possibility of a reunification of Marxist theory and mass revolutionary practice in the West had reappeared. Such a reunification would, in his view, mean the extinction of the Western Marxist tradition, whose existence was defined by the very divorce it might overcome.[142] Russell Jacoby offered a different assessment, arguing against Anderson's view of Western Marxism as an "unfortunate detour". Jacoby contends that the tradition's philosophical turn was an "advance to a reexamination of Marxism" necessary to challenge the "ethos of success" that drained the critical impulse of orthodox Marxism.[143] For Jacoby, the "dialectic of defeat" that defines Western Marxism is not simply a sign of failure, but a theoretical approach that salvages insights from a history of loss, arguing in 1981 that "defeat may enclose future victories" in a way that the uncritical imitation of past successes cannot.[144]

J. G. Merquior argues that the movement's defining flaw was its embrace of Kulturkritik, which led it to reject historical analysis in favor of sweeping, often romantic, indictments of modern civilization. In his view, this resulted in a "theoreticism" that produced little of value for sociological or historical understanding.[145] He further contends that while Western Marxism claimed to revive Hegel, it often adopted an ethicist or moralist posture more akin to Johann Gottlieb Fichte or even neo-Kantianism, pitting an abstract "ought" against the reality of the historical process.[146] The Frankfurt School's critique of instrumental reason, for example, expanded into a wholesale condemnation of science and technology, which Lucio Colletti described as a view where "science was... a child of capital."[147]

In the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of totality at the heart of Western Marxism came under sustained attack from post-structuralism. Thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard rejected what they saw as the totalizing and repressive nature of "grand narratives" like Marxism.[148] Foucault argued that the desire to understand "the whole of society" was a dangerous illusion that ignored the dispersed, localized, and "polymorphous techniques of subjugation" that constitute power.[149] For Lyotard, the "nostalgia for the whole and the one" was a terroristic impulse that must be resisted.[150] This challenge led many former Western Marxists to abandon the concept of totality in favor of a new emphasis on difference, fragmentation, and contingency.[151]

See also

[edit]- Budapest School

- Critical theory

- Cultural studies

- Freudo-Marxism

- Hegelian Marxism

- List of contributors to Marxist theory

- Marxist cultural analysis

- Marxist humanism

- Neo-Marxism

- Open Marxism

- Political Marxism

- Post-Marxism

- Praxis School

- Situationist International

- Structural Marxism

- Critique of political economy

References

[edit]- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 10.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 1, fn. 2.

- ^ a b Jacoby 1981, p. 59.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 11.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 1.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 29.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 42.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 16–20, 42.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 32.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 7, 26, 28.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 7, 12, 15.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 15.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 13, 68.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 2.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 17.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 13.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 100.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Jacoby 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Jacoby 1981, p. 53.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 39.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 273.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 1976, p. 49.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 44.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 11.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 50.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 53.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 54.

- ^ a b c Jay 1984, p. 12.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 55.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 58.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Merquior 1986, p. 15.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 255.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Anderson 1976, p. 57.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 341.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 324.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 59, 61–67.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 14, fn. 26.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 265.

- ^ a b Jay 1984, p. 14.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 76.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c d Merquior 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 77.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 27, 33.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 376.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 88.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 89, 97–98.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 93.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 61.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 59, 67–68.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 74.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 62, 77.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 81.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 174.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 85.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 82.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 83.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 109.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 67, 89.

- ^ a b Goode 1979, p. 9.

- ^ Goode 1979, pp. 72, 74.

- ^ Goode 1979, p. 78.

- ^ a b Goode 1979, p. 74.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 83.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 220.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 94–95.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 192.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 100.

- ^ a b Anderson 1976, p. 80.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 101.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 111.

- ^ Goode 1979, p. 79.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 196.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 111–112, 121.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 110.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 283.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 198.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 112.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 113–14.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 288.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 348.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 121, 123, 127.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 125, 141, 144.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 37.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 276.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Jacoby 1991, p. 581.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 26.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 312.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 141.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 351.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b c Soper 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 147.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 394.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 150.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 405–407.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 39.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 152.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 427.

- ^ McLellan 1998, p. 326.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 427, 431.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 431.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 435.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 453.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 453–454.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 449, 455.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 421.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 431.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978, p. 449.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 159, 161.

- ^ Anderson 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 164.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 167.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 506.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 176–178, 183.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 496, 503.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 115.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, pp. 115–16.

- ^ Anderson 1976, pp. 95, 101.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 7.

- ^ Jacoby 1981, p. 4.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 186.

- ^ Merquior 1986, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Merquior 1986, p. 184.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 510, 515.

- ^ Jay 1984, pp. 520–21, 525.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 515.

- ^ Jay 1984, p. 513.

Works cited

[edit]- Anderson, Perry (1976). Considerations on Western Marxism. London: NLB. ISBN 9780860917205.

- Goode, Patrick (1979). Karl Korsch: A Study in Western Marxism. London: The Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-1-349-03658-5.

- Jacoby, Russell (1981). Dialectic of Defeat: Contours of Western Marxism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23915-X.

- Jacoby, Russell (1991). "Western Marxism". In Bottomore, Tom; Harris, Laurence; Kiernan, V. G.; Miliband, Ralph (eds.). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 581–584. ISBN 978-0-631-16481-4.

- Jay, Martin (1984). Marxism and Totality: The Adventures of a Concept from Lukács to Habermas. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05096-7.

- Kołakowski, Leszek (1978). Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. 3: The Breakdown. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-824570-X.

- McLellan, David (1998). Marxism after Marx: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-72207-8.

- Merquior, J. G. (1986). Western Marxism. London: Paladin. ISBN 0-586-08454-1.

- Soper, Kate (1986). Humanism and Anti-Humanism. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-162-931-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Kevin (1995). Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism. University of Illinois Press.

- Arato, Andrew; Breines, Paul (1979). The Young Lukács and the Origins of Western Marxism. New York: The Seabury Press. ISBN 0-8164-9359-6.

- Bahr, Ehrhard (2008). Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25795-5.

- Fetscher, Iring (1971). Marx and Marxism. New York: Herder and Herder.

- Gottlieb, Roger S. (1989). An Anthology of Western Marxism. Oxford University Press.

- Grahl, Bart; Piccone, Paul, eds. (1973). Towards a New Marxism. St. Louis, Missouri: Telos Press.

- Howard, Dick; Klare, Karl E., eds. (1972). The Unknown Dimension: European Marxism Since Lenin. New York: Basic Books.

- Jones, Gareth Stedman (1983). Western Marxism: a Critical Reader. South Yarra: MacMillan Education Australia. ISBN 0902308297.

- Kellner, Douglas. "Western Marxism" (PDF). Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Korsch, Karl (1970) [1923]. Marxism and Philosophy. Translated by Halliday, Fred. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-0-85345-153-2.

- Lukács, György (1971) [1923]. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. London: Merlin Press. ISBN 978-0-850-36197-1.

- McInnes, Neil (1972). The Western Marxists. New York: Library Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1973) [1955]. Adventures of the Dialectic. Translated by Bien, Joseph. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-0404-4.

- Stahl, Titus (2023) [2013]. "Georg [György] Lukács". In Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- Van der Linden, Marcel (2007). Western Marxism and the Soviet Union. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004158757.i-380. ISBN 978-90-04-15875-7.

- "Western and Heterodox Marxism". Marx200.org. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2020.