Grundrisse

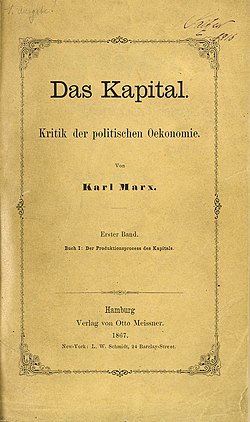

Cover of the 1953 German edition | |

| Author | Karl Marx |

|---|---|

| Original title | Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie (Rohentwurf) |

| Language | German |

| Subjects | |

| Published |

|

| Publisher | Foreign Languages Publishing House |

| Publication place | Moscow, Soviet Union |

Published in English | 1973 |

| The work was written in 1857–1858 and published posthumously. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

| Outline |

The Grundrisse der Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie (Rohentwurf) (German: [ˈɡʁʊntˌʁɪsə]; lit. "Foundations/Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft)") is a lengthy, unfinished manuscript written by Karl Marx in the winter of 1857–1858. Comprising seven notebooks of economic studies, the work represents the first major draft of Marx's critique of political economy and is widely considered the preparatory work for his magnum opus, Das Kapital. The text was written for self-clarification during the Panic of 1857, and remained unpublished during his lifetime. A first edition was published in German in Moscow in 1939 and 1941, but the work only became widely available and influential in the 1960s and 1970s; a full English translation appeared in 1973.

The manuscript's scope is vast, covering all six sections of Marx's intended economic project. It explores key themes such as alienation, the nature of capital as a self-expanding process or "value in motion," and an analysis of pre-capitalist economic forms. It contains the well-known "Fragment on Machines," in which Marx analyses the effects of automation, foreseeing a point where social knowledge becomes a direct productive force, a concept he termed the "general intellect." The work also outlines the dialectical method Marx considered "scientifically correct," which proceeds from simple abstract categories to an understanding of the concrete world as a "rich totality of many determinations and relations."

Because of its raw, experimental style and its late publication, the Grundrisse is often described as the "laboratory" for the more structured arguments of Das Kapital. The Ukrainian Marxist Roman Rosdolsky's seminal study, The Making of Marx's 'Capital' (1968), was crucial in establishing the manuscript's importance as the link between Marx's early philosophical writings and his later economic analysis, with some scholars such as David McLellan calling it the "centrepiece" of his entire corpus.[1] Its eventual publication had a profound impact on Marxist scholarship, revealing a more philosophical and historical dimension to Marx's thought and sparking diverse interpretations among thinkers from Louis Althusser to the Autonomist school.

Background and publication

[edit]

Karl Marx wrote the Grundrisse manuscripts during the winter of 1857–1858 while living in exile in London. The work was prompted by the Panic of 1857, a major global financial crisis that Marx believed might be the final, catastrophic crisis of capitalism, spurring on a revolutionary upheaval.[2][3][4] He worked frantically to outline his economic theories, resulting in a series of seven notebooks written for self-clarification rather than direct publication. In a December 1857 letter to Friedrich Engels, Marx described his progress: "I am working like mad all night and every night collating my economic studies so that I at least get the outlines clear before the déluge [the flood]".[5] David Harvey describes the text as "a set of notes that Marx was frantically writing to himself at a rather frantic time."[6] Another motivation for the work was Marx's desire to deal with the "false brothers" of the socialist workers' movement, the Proudhonists. The Grundrisse begins with a devastating polemic against the Proudhonist theories of labour-money, particularly the ideas of Alfred Darimon.[7][8]

The manuscript begins with an introduction that was actually a separate text written earlier, about which Marx himself had "serious reservations," possibly feeling it was too abstract or Hegelian.[9] In his 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, he stated that he was omitting the introduction because "it seems to me confusing to anticipate results which still have to be substantiated".[10] For the rest of his life, the notebooks remained unpublished and largely unknown. The first sections to be published were the Introduction and an essay on Frédéric Bastiat and Henry Charles Carey, which were released by Karl Kautsky in 1903 and 1904.[11][12] The existence of the seven main notebooks was not announced until 1923 by David Riazanov, director of the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow.[11][13] They were first published in German in Moscow in two volumes in 1939 and 1941, but this edition received little attention. A more accessible single-volume German edition was published in East Berlin in 1953.[14][11]

The manuscript's significance in the English-speaking world grew after the Ukrainian Marxist scholar Roman Rosdolsky discovered a rare copy in the New York Public Library in 1947. Having survived years in Nazi concentration camps, Rosdolsky devoted much of his subsequent life to studying the text.[14] His seminal work, The Making of Marx's 'Capital' (published in German in 1968 and in English in 1977), was the first major study to systematically analyse the Grundrisse and establish its importance as the crucial link between Marx's early philosophical writings and the economic analysis of Das Kapital.[14][15] Before the full English translation, a widely influential selection of extracts was translated and edited by David McLellan in 1971. In his preface, McLellan described the Grundrisse as the "last of [Marx's] major writings to be translated into English" and presented his edition with the "modest aim of making available the most important passages of this vital text".[16] The first full English translation, by Martin Nicolaus, was published in 1973 by Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, an event that Harvey states had a "huge impact upon" Marxist scholarship, including his own work.[14]

Style and method

[edit]The Grundrisse is stylistically unique among Marx's major works. Harvey categorises Marx's writing into four types—journalism, published works like Das Kapital, experimental manuscripts, and notes written for self-clarification. He places the Grundrisse firmly in the fourth category, describing its style as "Marx writing purely for himself, using whatever tools and ideas that he has in his head, prepared to unleash a stream of his own consciousness."[17] This results in a text that is at once "exciting, frustrating, imaginative and sometimes boringly repetitive," where concepts are often fluid and meanings evolve as the text unfolds.[18] A significant challenge for readers is distinguishing whether Marx is developing his own conceptual framework or reporting on and critiquing the views of other political economists.[17]

Methodologically, the Grundrisse outlines what Marx considered the "scientifically correct method" for political economy. This method begins by rejecting a start from "the real and the concrete," such as a country's population, which he dismisses as a "chaotic conception of the whole."[19][20] Instead, the inquiry must first proceed analytically from the "imagined concrete" toward "ever more simple concepts" and "thinner abstractions" like labour, division of labour, need, and exchange value.[21] From these simplest determinations, the journey must be "retraced" by ascending from the abstract back to the concrete. The goal is to reproduce the concrete in the mind, not as a chaotic whole, but as a "rich totality of many determinations and relations."[22][23] For Marx, the concrete is "concrete because it is the concentration of many determinations, hence unity of the diverse."[24]

The central methodological abstraction employed throughout the Grundrisse is the concept of "capital in general" (Kapital im Allgemeinen). This concept is used to analyse the fundamental characteristics of capital as a whole, separate from the particular forms it takes in the real world as "many capitals" interacting through competition, credit, and the state.[25][26] The investigation of "capital in general" allows Marx to abstract from real-world phenomena to grasp the "inner living organisation" and inherent laws of the capitalist mode of production before analysing how those laws manifest in the concrete realities of competition.[27]

Key themes

[edit]Totality and circulation

[edit]According to David Harvey, the Grundrisse is fundamentally structured as an inquiry into the different "circulation processes" that constitute capital as an "organic totality".[28] Marx depicts capital not as a thing but as a complex ecosystem in constant formation, an open and evolving system defined by its internal contradictions and its metabolic relation to nature and human culture.[29] This totality consists of multiple, distinct circulation processes that are simultaneously "autonomous and independent but subsumed within" the whole system.[30] Harvey identifies several such circulatory systems that Marx analyses:

- The circulation of commodities through exchange.

- The circulation of money as money.

- The circulation of the capacity to labour.

- The circulation of money as capital.

- The circulation of fixed capital.

- The circulation of interest-bearing capital.[31]

The interconnectedness of these circuits means that a failure in one threatens the entire system, similar to how the failure of a vital organ affects a biological organism. This holistic framework, Harvey argues, is essential to understanding Marx's analysis of capital's dynamics, where production, consumption, distribution, and realisation are not separate spheres but interconnected moments in a single, continuous flow of value.[30]

Alienation and the critique of individualism

[edit]

The Grundrisse begins with a critique of the isolated, rational individual—epitomised by Robinson Crusoe—that served as the foundation for 18th-century political economy.[32][33] Marx argues that this "isolated individual" is not a natural starting point but a historical product of a society based on market exchange, which dissolves earlier collective forms like the kinship group or tribe.[34][35]

This analysis leads to a radical reformulation of Marx's earlier concept of alienation. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, alienation was presented as a humanist concept, where capital frustrates the realisation of an essential human nature or "species being".[36][37] In the Grundrisse, however, alienation becomes a concrete, historical condition where the labourer is separated from the objective conditions of labour.[37][38] Scholar David McLellan argues that the Grundrisse treats the themes of alienation from the Paris Manuscripts in a "much 'maturer' way", having achieved a "synthesis of his ideas on philosophy and economics".[39] For McLellan, the concept of alienation is "central to most of the more important passages of the Grundrisse".[40]

The central thesis, which Harvey identifies as the "keystone" of this theory, is that "Individuals are now ruled by abstractions, whereas earlier they depended on one another. The abstraction, or idea, however, is nothing more than the theoretical expression of those material relations which are their lord and master."[41][42][43] These abstractions—value, money, capital—are not mere ideas but objective social forces that emerge from market relations. This alienated condition applies not just to the worker but also to the capitalist, who is not a free agent but is compelled to act by the "coercive laws of competition" which dictate the endless accumulation of capital.[41] The seeming freedom of the market individual masks a deeper subordination to these impersonal, alien powers.[44]

Capital as a self-expanding process

[edit]A foundational insight developed throughout the Grundrisse is that capital cannot be understood as a thing (like money or machinery) but must be grasped as a process. Marx states definitively: "Capital is not a simple relation, but a process, in whose various moments it is always capital."[45][46][47] Harvey encapsulates this as "value in motion".[48] This process involves capital passing through different forms—money, commodities (labour power and means of production), the production process, the newly created commodity, and back to money—in a continuous circuit.

Crucially, this circuit is not a simple, repetitive circle but a "spiral, an expanding curve."[49] The process is one of self-realisation and self-expansion; capital must constantly multiply itself to remain capital. This inherent drive for endless, cumulative, and exponential growth is what distinguishes the circulation of capital from simple commodity circulation.[50] The source of this expansion is surplus value, which Marx demonstrates cannot arise from the sphere of exchange (where equivalents are traded) but must originate in the process of production through the exploitation of labour power.[51][52] The appropriation of "alien labour" is therefore the "living source of value" that animates capital's endless expansion.[53]

The "Fragment on Machines"

[edit]

One of the most widely discussed sections of the Grundrisse is the "Fragment on Machines," where Marx analyses the ultimate consequences of capital's tendency to develop the productive forces.[54][55][56] He describes the emergence of an "automatic system of machinery" where the worker is reduced to a mere "conscious linkage," a watchman and regulator of a production process that is now dominated by machinery rather than by direct human labour.[57][58]

In this system, science, knowledge, and the "general productive forces of the social brain" are absorbed into capital, particularly as fixed capital. This knowledge confronts the worker as an "alien power" embodied in the machine system.[59][58] Marx argues that as this process develops, "direct labour and its quantity disappear as the determinant principle of production." Since labour time is the measure of value, this trend undermines the very foundation of capital. He concludes that "production based on exchange value breaks down" and that "Capital thus works towards its own dissolution as the form dominating production."[60][61][62]

In the same passage, Marx famously coins the term "general intellect" to describe the collective social knowledge that has become a "direct force of production," objectified in the system of machinery.[63][58] This development creates the material conditions for a new society where wealth is no longer measured by labour time but by "disposable time," allowing for the "free development of individualities."[64][65][66]

Pre-capitalist formations

[edit]A significant portion of the text is devoted to an analysis of pre-capitalist economic formations. In this section, Marx explores the historical and geographical processes that lead to the "dissolution" of earlier social forms (such as those based on communal property, slavery, or feudalism) and create the essential preconditions for the rise of capital.[67][68] The key precondition is the separation of the worker from the means of production, creating a class of "free labourers" who must sell their labour capacity to survive.[69][70]

Harvey notes that Marx's approach here departs from a rigid, unilinear theory of history (such as the sequence of Asiatic, ancient, feudal, and bourgeois modes of production mentioned in the 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy).[69][71][72] Instead, the Grundrisse presents a more fluid and contingent evolutionary process, differentiated by geography, culture, and specific historical circumstances. Marx examines different paths, such as the "Asiatic" form, characterised by communal property and a despotic state, and the "Germanic" form, based on individual households within a loose communal structure.[73][74] The central theme is how the "natural unity of labour with its material" conditions is broken, leading to the alienation of workers from the land and their tools, and establishing the property relations necessary for capital's emergence.[69]

Relationship to Das Kapital

[edit]

The Grundrisse is broadly considered the first draft of Marx's critique of political economy, and its raw, exploratory nature provides insight into the intellectual labour that led to his more structured and polished work, Das Kapital. However, some scholars argue that this view diminishes its significance, seeing it not as a mere preparatory work but as a major text in its own right. David McLellan, for instance, contends that the Grundrisse is "much more than a rough draft of Capital" and is, in a sense, "the completest of [Marx's] works" as it contains "a synthesis of the various strands of Marx's thought".[75] The Italian Autonomist Antonio Negri similarly questions whether Das Kapital constitutes the most developed point in Marx's analysis, arguing that the Grundrisse is a "text dedicated to revolutionary subjectivity" that forces a recognition of its profound differences from his later, more objectified work.[76]

One of the most significant differences lies in the theory of value. In the Grundrisse, Marx's concept of value is not yet fully consolidated; he often uses the term interchangeably with "exchange-value" and treats it as a fusion of labour inputs and market prices. This contrasts sharply with Das Kapital, where a clear and rigorous distinction is made between value, exchange-value, and use-value.[77][78] Similarly, while the Grundrisse contains the first full elaboration of the concept of surplus value, its presentation is convoluted compared to the systematic explanation provided in Das Kapital.[79][80]

The original six-book plan

[edit]The manuscript also contains several different outlines and plans for Marx's projected magnum opus, which he would later abandon or modify.[81] The initial structural plan, formulated in 1857 and outlined in a letter to Ferdinand Lassalle, was far broader than the eventual scope of Das Kapital.[82] The project was divided into six books:[83][84]

- The Book on Capital

- The Book on Landed Property

- The Book on Wage-Labour

- The Book on the State

- The Book on Foreign Trade

- The Book on the World Market and Crises

According to Rosdolsky's analysis, the Grundrisse manuscript corresponds almost entirely to the first part of the first book, which was dedicated to "capital in general".[85] Over the subsequent decade, Marx revised this plan significantly. The last three books on the State, Foreign Trade, and the World Market were postponed and never written.[86] The material for the books on Landed Property and Wage-Labour was eventually incorporated into the final three volumes of Das Kapital. Thus, the vast six-book project was ultimately condensed into the single, though monumental, work on capital.[86] The change in this plan, Rosdolsky argues, reflects a methodological shift as Marx moved from a structure that separated out the main economic categories to one that integrated them within the total process of capital's reproduction.[87]

Influence and interpretation

[edit]For decades after it was written, the Grundrisse had no influence, as it remained unpublished. Its gradual emergence in the mid-20th century, particularly after the work of Roman Rosdolsky and the English translation in 1973, had a profound impact on Marxist theory.[14][88] It revealed a "different" Marx than the one known primarily through Das Kapital, one more concerned with themes of alienation, historical transformation, and the philosophical underpinnings of his critique. Rosdolsky's The Making of Marx's 'Capital' (1968) was the first work to systematically analyse the manuscript's structure, its relation to Hegel's Science of Logic, and its importance as the laboratory where the core concepts of Das Kapital were first forged.[15][88]

David McLellan, whose 1971 selection of texts from the Grundrisse was one of the first to make it accessible to an English-speaking audience, argued that the manuscript is the "centrepiece" of Marx's work, revealing a continuity in his thought from the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 to Das Kapital.[89] McLellan emphasised the Hegelianism of the Grundrisse, noting that its most Hegelian parts were written before Marx re-read Hegel's Logic, and argued that the theme of alienation remained central to Marx's mature thought.[40] He viewed the Grundrisse as the "most fundamental" of Marx's works because it synthesised his philosophical and economic ideas in a way that his other writings did not.[90] In contrast, Louis Althusser used the Grundrisse’s Introduction to reinforce his argument for a sharp epistemological break between the early, humanist Marx and the later, scientific Marx. For Althusser, the text demonstrated a rigorous scientific method that was distinct from Hegelian historicism and focused on synchronic structure rather than historical genesis.[91]

The "Fragment on Machines" and the concept of the "general intellect" have been particularly influential on post-war thinkers, especially in the Autonomist Marxist tradition in Italy. Thinkers like Antonio Negri, in his work Marx Beyond Marx: Lessons on the Grundrisse (1991), have viewed the Grundrisse as the "summit of Marx's revolutionary thought", a text more important than Capital because of its focus on revolutionary subjectivity.[92] For Negri, the Grundrisse provides the basis for a "political reading" of Marx where every economic category clarifies the "antagonistic nature of the class struggle" between two active subjects: capital and the working class.[93] These passages have been used to argue for the emergence of "cognitive capitalism" or an "information economy" where knowledge, rather than factory labour, is the primary source of value.[94] Harvey considers this a "rather presumptuous" interpretation, given that Marx uses the term "general intellect" only once in his entire corpus of work.[63]

David Harvey's own interpretation, presented in his A Companion to Marx's Grundrisse (2023), argues that the central, and often overlooked, framework of the text is Marx's concept of capital as an evolving "totality" composed of multiple, interacting circulation processes.[95] Harvey contends that understanding this holistic, ecosystemic model is key to unlocking the Grundrisse’s insights into the nature of capital and its crises.[96]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McLellan 1980, p. 9.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 29.

- ^ Musto 2008c, p. 149.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 10.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 30.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 23.

- ^ Choat 2016, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c Choat 2016, p. 181.

- ^ Hobsbawm 2008, p. xxi.

- ^ Musto 2008d, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 2023, p. 50.

- ^ a b Rosdolsky 1977, p. xv.

- ^ McLellan 1980, p. ix.

- ^ a b Harvey 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 43.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Musto 2008b, p. 15.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Choat 2016, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 44.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, pp. 41, 63.

- ^ Choat 2016, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 69.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 14, 18.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 14.

- ^ a b Harvey 2023, p. 34.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 18.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 24.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 26.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 26.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 27.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 71.

- ^ a b Choat 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Carver 2008, p. 55.

- ^ McLellan 1980, p. 14.

- ^ a b McLellan 1980, p. 13.

- ^ a b Harvey 2023, p. 72.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 438.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 70.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 97.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 102.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 30.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 98, 104.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 95.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 134.

- ^ Dussel 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 98, 307.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 271.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 425.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 159.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 276, 294.

- ^ a b c Choat 2016, p. 160.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 279.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 281, 286.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 163.

- ^ a b Harvey 2023, p. 297.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 305.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 426.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 147.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 196.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 129.

- ^ a b c Harvey 2023, p. 185.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 119.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 436.

- ^ Wood 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 187, 191.

- ^ Choat 2016, pp. 123–125.

- ^ McLellan 1980, pp. 12, 15, footnote 4

- ^ Negri 1991, pp. 5, 8.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 92.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 52.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 133.

- ^ Dussel 2008, p. 68.

- ^ Harvey 2023, pp. 49, 89, 103, 109.

- ^ Choat 2016, pp. 11, 22.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 34.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, pp. 36, 61.

- ^ a b Rosdolsky 1977, p. 33.

- ^ Rosdolsky 1977, p. 75.

- ^ a b Choat 2016, p. 182.

- ^ McLellan 1980, pp. 9, 12.

- ^ McLellan 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Choat 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Negri 1991, pp. xix, 18.

- ^ Negri 1991, p. xx.

- ^ Postone 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 358.

- ^ Harvey 2023, p. 361.

Works cited

[edit]- Choat, Simon (2016). Marx's 'Grundrisse'. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4725-3190-2.

- Harvey, David (2023). A Companion to Marx's Grundrisse (eBook ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-80429-098-9.

- McLellan, David (1980). Marx's Grundrisse (2nd ed.). The Macmillan Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-333-28151-2.

- Musto, Marcello, ed. (2008a). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Carver, Terrell (2008). "Marx's conception of alienation in the Grundrisse". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 48–66. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Dussel, Enrique (2008). "The discovery of the category of surplus value". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Hobsbawm, Eric (2008). "Foreword". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. xx–xxiii. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Musto, Marcello (2008b). "History, production and method in the 1857 'Introduction'". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 3–32. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Musto, Marcello (2008c). "Marx's life at the time of the Grundrisse: biographical notes on 1857–8". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 149–161. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Musto, Marcello (2008d). "Dissemination and reception of the Grundrisse in the world: introduction". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 179–188. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Postone, Moishe (2008). "Rethinking Capital in light of the Grundrisse". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 120–137. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins (2008). "Historical materialism in 'Forms which Precede Capitalist Production'". In Musto, Marcello (ed.). Karl Marx's Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political economy 150 years later. Routledge. pp. 79–92. ISBN 978-0-415-43749-3.

- Negri, Antonio (1991). Marx Beyond Marx: Lessons on the Grundrisse. Translated by Harry Cleaver, Michael Ryan and Maurizio Viano. Autonomedia. ISBN 00-89789-018-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Rosdolsky, Roman (1977). The Making of Marx's 'Capital'. Translated by Pete Burgess. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-904383-37-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Bottomore, Tom, ed. A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

- Elliott, John E., Marx's Grundrisse: Vision of capitalism's creative destruction. Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics. Winter 1978–79, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 148–169.

- Harvey, David. The Limits of Capital. London: Verso, 2006.

- Lallier, Adalbert G. The Economics of Marx's Grundrisse: an Annotated Summary. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

- Mandel, Ernest. The Formation of the Economic Thought of Karl Marx: 1843 to Capital. London: Verso, 2015.

- Mandel, Ernest. Marxist Economic Theory. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970.

- Postone, Moishe. Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Tronti, Mario. Workers and Capital. London: Verso, 2019.

- Uchida, Hiroshi. Marx's Grundrisse and Hegel's Logic. . Terrell Carver (ed.). London: Routledge, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Complete text (English html format), Marxists Internet Archive, www.marxists.org/