Portal:Minerals

Portal maintenance status: (May 2019)

|

The Minerals Portal

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.

The geological definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living organisms. However, some minerals are often biogenic (such as calcite) or organic compounds in the sense of chemistry (such as mellite). Moreover, living organisms often synthesize inorganic minerals (such as hydroxylapatite) that also occur in rocks.

The concept of mineral is distinct from rock, which is any bulk solid geologic material that is relatively homogeneous at a large enough scale. A rock may consist of one type of mineral or may be an aggregate of two or more different types of minerals, spacially segregated into distinct phases.

Some natural solid substances without a definite crystalline structure, such as opal or obsidian, are more properly called mineraloids. If a chemical compound occurs naturally with different crystal structures, each structure is considered a different mineral species. Thus, for example, quartz and stishovite are two different minerals consisting of the same compound, silicon dioxide. (Full article...)

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, and their utilization. (Full article...)

Selected articles

-

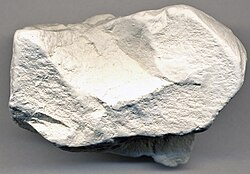

Image 1Beachy Head is a part of the extensive Southern England Chalk Formation.

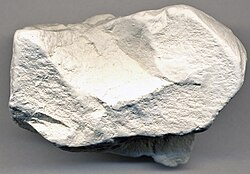

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed under the sea by the accumulation and lithification of hard parts of organisms, mostly microscopic plankton, which had settled to the sea floor. Chalk is common throughout Western Europe, where deposits underlie parts of France, and steep cliffs are often seen where they meet the sea in places such as the Dover cliffs on the Kent coast of the English Channel.

Chalk is mined for use in industry, such as for quicklime, bricks and builder's putty, and in agriculture, for raising pH in soils with high acidity. It is also used for "blackboard chalk" for writing and drawing on various types of surfaces, although these can also be manufactured from other carbonate-based minerals, or gypsum. (Full article...) -

Image 2

Mineralogy applies principles of chemistry, geology, physics and materials science to the study of minerals

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, and their utilization. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·nH2O); its water content may range from 3% to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6% and 10%. Due to the amorphous (chemical) physical structure, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms of silica, which are considered minerals. It is deposited at a relatively low temperature and may occur in the fissures of almost any kind of rock, being most commonly found with limonite, sandstone, rhyolite, marl, and basalt.

The name opal is believed to be derived from the Sanskrit word upala (उपल), which means 'jewel', and later the Greek derivative opállios (ὀπάλλιος).

There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. Precious opal displays play-of-color (iridescence); common opal does not. Play-of-color is defined as "a pseudo chromatic optical effect resulting in flashes of colored light from certain minerals, as they are turned in white light." The internal structure of precious opal causes it to diffract light, resulting in play-of-color. Depending on the conditions in which it formed, opal may be transparent, translucent, or opaque, and the background color may be white, black, or nearly any color of the visual spectrum. Black opal is considered the rarest, while white, gray, and green opals are the most common. (Full article...) -

Image 4

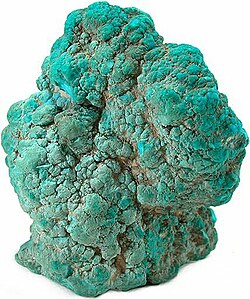

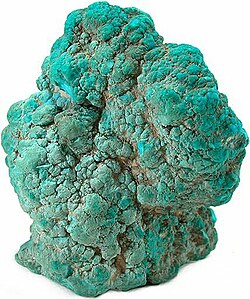

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone for millennia due to its hue.

The robin egg blue or sky blue color of the Persian turquoise mined near the modern city of Nishapur, Iran, has been used as a guiding reference for evaluating turquoise quality.

Like most other opaque gems, turquoise has been devalued by the introduction of treatments, imitations, and synthetics into the market. (Full article...) -

Image 5

Micas (/ˈmaɪkəz/ MY-kəz) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into fragile elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is common in igneous and metamorphic rock and is occasionally found as small flakes in sedimentary rock. It is particularly prominent in many granites, pegmatites, and schists, and "books" (large individual crystals) of mica several feet across have been found in some pegmatites.

Micas are used in products such as drywalls, paints, and fillers, especially in parts for automobiles, roofing, and in electronics. The mineral is used in cosmetics and food to add "shimmer" or "frost". (Full article...) -

Image 6Malachite from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Malachite (/ˈmæl.əˌkaɪt/) is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, with the formula Cu2CO3(OH)2. This opaque, green-banded mineral crystallizes in the monoclinic crystal system, and most often forms botryoidal, fibrous, or stalagmitic masses, in fractures and deep, underground spaces, where the water table and hydrothermal fluids provide the means for chemical precipitation. Individual crystals are rare, but occur as slender to acicular prisms. Pseudomorphs after more tabular or blocky azurite crystals also occur. (Full article...) -

Image 7Galena with minor pyrite

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crystallizes in the cubic crystal system often showing octahedral forms. It is often associated with the minerals sphalerite, calcite and fluorite.

As a pure specimen held in the hand, under standard temperature and pressure, galena is insoluble in water and so is almost non-toxic. Handling galena under these specific conditions (such as in a museum or as part of geology instruction) poses practically no risk; however, as lead(II) sulfide is reasonably reactive in a variety of environments, it can be highly toxic if swallowed or inhaled, particularly under prolonged or repeated exposure. (Full article...) -

Image 8

The diamond crystal structure belongs to the face-centered cubic lattice, with a repeated two-atom pattern.

In crystallography, a crystal system is a set of point groups (a group of geometric symmetries with at least one fixed point). A lattice system is a set of Bravais lattices (an infinite array of discrete points). Space groups (symmetry groups of a configuration in space) are classified into crystal systems according to their point groups, and into lattice systems according to their Bravais lattices. Crystal systems that have space groups assigned to a common lattice system are combined into a crystal family.

The seven crystal systems are triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, trigonal, hexagonal, and cubic. Informally, two crystals are in the same crystal system if they have similar symmetries (though there are many exceptions). (Full article...) -

Image 9

Diamond is a solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odorless, strong, brittle solid, colorless in pure form, a poor conductor of electricity, and insoluble in water. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the chemically stable form of carbon at room temperature and pressure, but diamond is metastable and converts to it at a negligible rate under those conditions. Diamond has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of any natural material, properties that are used in major industrial applications such as cutting and polishing tools.

Because the arrangement of atoms in diamond is extremely rigid, few types of impurity can contaminate it (two exceptions are boron and nitrogen). Small numbers of defects or impurities (about one per million of lattice atoms) can color a diamond blue (boron), yellow (nitrogen), brown (defects), green (radiation exposure), purple, pink, orange, or red. Diamond also has a very high refractive index and a relatively high optical dispersion.

Most natural diamonds have ages between 1 billion and 3.5 billion years. Most were formed at depths between 150 and 250 kilometres (93 and 155 mi) in the Earth's mantle, although a few have come from as deep as 800 kilometres (500 mi). Under high pressure and temperature, carbon-containing fluids dissolved various minerals and replaced them with diamonds. Much more recently (hundreds to tens of million years ago), they were carried to the surface in volcanic eruptions and deposited in igneous rocks known as kimberlites and lamproites.

Synthetic diamonds can be grown from high-purity carbon under high pressures and temperatures or from hydrocarbon gases by chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Natural and synthetic diamonds are most commonly distinguished using optical techniques or thermal conductivity measurements. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Rutile is an oxide mineral composed of titanium dioxide (TiO2), the most common natural form of TiO2. Rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known, including anatase, akaogiite, and brookite.

Rutile has one of the highest refractive indices at visible wavelengths of any known crystal and also exhibits a particularly large birefringence and high dispersion. Owing to these properties, it is useful for the manufacture of certain optical elements, especially polarization optics, for longer visible and infrared wavelengths up to about 4.5 micrometres. Natural rutile may contain up to 10% iron and significant amounts of niobium and tantalum.

Rutile derives its name from the Latin rutilus ('red'), in reference to the deep red color observed in some specimens when viewed by transmitted light. Rutile was first described in 1803 by Abraham Gottlob Werner using specimens obtained in Horcajuelo de la Sierra, Madrid (Spain), which is consequently the type locality. (Full article...) -

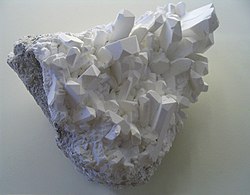

Image 11

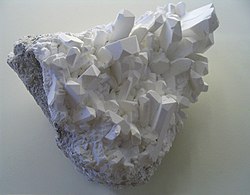

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, drywall and blackboard or sidewalk chalk. Gypsum also crystallizes as translucent crystals of selenite. It forms as an evaporite mineral and as a hydration product of anhydrite. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness defines gypsum as hardness value 2 based on scratch hardness comparison.

Fine-grained white or lightly tinted forms of gypsum known as alabaster have been used for sculpture by many cultures including Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Rome, the Byzantine Empire, and the Nottingham alabasters of Medieval England. (Full article...) -

Image 12

Kaolinite (/ˈkeɪ.ələˌnaɪt, -lɪ-/ KAY-ə-lə-nyte, -lih-; also called kaolin) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2Si2O5(OH)4. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one "tetrahedral" sheet of silicate tetrahedra (SiO4) linked to one "octahedral" sheet of aluminate octahedrons (AlO2(OH)4) through oxygen atoms on one side, and another such sheet through hydrogen bonds on the other side.

Kaolinite is a soft, earthy, usually white, mineral (dioctahedral phyllosilicate clay), produced by the chemical weathering of aluminium silicate minerals like feldspar. It has a low shrink–swell capacity and a low cation-exchange capacity (1–15 meq/100 g).

Rocks that are rich in kaolinite, and halloysite, are known as kaolin (/ˈkeɪ.əlɪn/) or china clay. In many parts of the world kaolin is colored pink-orange-red by iron oxide, giving it a distinct rust hue. Lower concentrations of iron oxide yield the white, yellow, or light orange colors of kaolin. Alternating lighter and darker layers are sometimes found, as at Providence Canyon State Park in Georgia, United States.

Kaolin is an important raw material in many industries and applications. Commercial grades of kaolin are supplied and transported as powder, lumps, semi-dried noodle or slurry. Global production of kaolin in 2021 was estimated to be 45 million tonnes, with a total market value of US $4.24 billion. (Full article...) -

Image 13

Corundum is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) typically containing traces of iron, titanium, vanadium, and chromium. It is a rock-forming mineral. It is a naturally transparent material, but can have different colors depending on the presence of transition metal impurities in its crystalline structure. Corundum has two primary gem varieties: ruby and sapphire. Rubies are red due to the presence of chromium, and sapphires exhibit a range of colors depending on what transition metal is present. A rare type of sapphire, padparadscha sapphire, is pink-orange.

The name "corundum" is derived from the Tamil-Dravidian word kurundam (ruby-sapphire) (appearing in Sanskrit as kuruvinda).

Because of corundum's hardness (pure corundum is defined to have 9.0 on the Mohs scale), it can scratch almost all other minerals. Emery, a variety of corundum with no value as a gemstone, is commonly used as an abrasive on sandpaper and on large tools used in machining metals, plastics, and wood. It is a black granular form of corundum, in which the mineral is intimately mixed with magnetite, hematite, or hercynite.

In addition to its hardness, corundum has a density of 4.02 g/cm3 (251 lb/cu ft), which is unusually high for a transparent mineral composed of the low-atomic mass elements aluminium and oxygen. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Talc, or talcum, is a clay mineral composed of hydrated magnesium silicate, with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent and lubricant. It is an ingredient in ceramics, paints, and roofing material. It is a main ingredient in many cosmetics. It occurs as foliated to fibrous masses, and in an exceptionally rare crystal form. It has a perfect basal cleavage and an uneven flat fracture, and it is foliated with a two-dimensional platy form.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 1 as the hardness of talc, the softest mineral. When scraped on a streak plate, talc produces a white streak, though this indicator is of little importance, because most silicate minerals produce a white streak. Talc is translucent to opaque, with colors ranging from whitish grey to green with a vitreous and pearly luster. Talc is not soluble in water, and is slightly soluble in dilute mineral acids.

Soapstone is a metamorphic rock composed predominantly of talc. (Full article...) -

Image 15

A rock containing three crystals of pyrite (FeS2). The crystal structure of pyrite is primitive cubic, and this is reflected in the cubic symmetry of its natural crystal facets.

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of these crystals:- Primitive cubic (abbreviated cP and alternatively called simple cubic)

- Body-centered cubic (abbreviated cI or bcc)

- Face-centered cubic (abbreviated cF or fcc)

Note: the term fcc is often used in synonym for the cubic close-packed or ccp structure occurring in metals. However, fcc stands for a face-centered cubic Bravais lattice, which is not necessarily close-packed when a motif is set onto the lattice points. E.g. the diamond and the zincblende lattices are fcc but not close-packed.

Each is subdivided into other variants listed below. Although the unit cells in these crystals are conventionally taken to be cubes, the primitive unit cells often are not. (Full article...) -

Image 16

Garnets ( /ˈɡɑːrnɪt/) are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

Garnet minerals, while sharing similar physical and crystallographic properties, exhibit a wide range of chemical compositions, defining distinct species. These species fall into two primary solid solution series: the pyralspite series (pyrope, almandine, spessartine), with the general formula [Mg,Fe,Mn]3Al2(SiO4)3; and the ugrandite series (uvarovite, grossular, andradite), with the general formula Ca3[Cr,Al,Fe]2(SiO4)3. Notable varieties of grossular include hessonite and tsavorite.

Although garnets are often associated with metamorphism, it can also occur in volcanic rocks on rare occasions. (Full article...) -

Image 17

Asbestos (/æsˈbɛstəs, æz-, -tɒs/ ass-BES-təs, az-, -toss) is a group of naturally occurring, toxic, carcinogenic and fibrous silicate minerals. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre (particulate with length substantially greater than width) being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere by abrasion and other processes. Inhalation of asbestos fibres can lead to various dangerous lung conditions, including mesothelioma, asbestosis, and lung cancer. As a result of these health effects, asbestos is considered a serious health and safety hazard.

Archaeological studies have found evidence of asbestos being used as far back as the Stone Age to strengthen ceramic pots, but large-scale mining began at the end of the 19th century when manufacturers and builders began using asbestos for its desirable physical properties. Asbestos is an excellent thermal and electrical insulator, and is highly fire-resistant, so for much of the 20th century, it was very commonly used around the world as a building material (particularly for its fire-retardant properties), until its adverse effects on human health were more widely recognized and acknowledged in the 1970s. Many buildings constructed before the 1980s contain asbestos.

The use of asbestos for construction and fireproofing has been made illegal in many countries. Despite this, around 255,000 people are thought to die each year from diseases related to asbestos exposure. In part, this is because many older buildings still contain asbestos; in addition, the consequences of exposure can take decades to arise. The latency period (from exposure until the diagnosis of negative health effects) is typically 20 years. The most common diseases associated with chronic asbestos exposure are asbestosis (scarring of the lungs due to asbestos inhalation) and mesothelioma (a type of cancer).

Many developing countries still support the use of asbestos as a building material, and mining of asbestos is ongoing, with the top producer, Russia, having an estimated production of 790,000 tonnes in 2020. (Full article...) -

Image 18The 423-carat (85 g) blue Logan Sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide (α-Al2O3) with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, cobalt, lead, chromium, vanadium, magnesium, boron, and silicon. The name sapphire is derived from the Latin word sapphirus, itself from the Greek word sappheiros (σάπφειρος), which referred to lapis lazuli. It is typically blue, but natural "fancy" sapphires also occur in yellow, purple, orange, and green colors; "parti sapphires" show two or more colors. Red corundum stones also occur, but are called rubies rather than sapphires. Pink-colored corundum may be classified either as ruby or sapphire depending on the locale. Commonly, natural sapphires are cut and polished into gemstones and worn in jewelry. They also may be created synthetically in laboratories for industrial or decorative purposes in large crystal boules. Because of the remarkable hardness of sapphires – 9 on the Mohs scale (the third-hardest mineral, after diamond at 10 and moissanite at 9.5) – sapphires are also used in some non-ornamental applications, such as infrared optical components, high-durability windows, wristwatch crystals and movement bearings, and very thin electronic wafers, which are used as the insulating substrates of special-purpose solid-state electronics such as integrated circuits and GaN-based blue LEDs. It occurs in association with ruby, zircon, biotite, muscovite, calcite, dravite and quartz. (Full article...) -

Image 19

A crystalline solid: atomic resolution image of strontium titanate. Brighter spots are columns of strontium atoms and darker ones are titanium-oxygen columns.

Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word crystallography is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρύσταλλος (krústallos; "clear ice, rock-crystal"), and γράφειν (gráphein; "to write"). In July 2012, the United Nations recognised the importance of the science of crystallography by proclaiming 2014 the International Year of Crystallography.

Crystallography is a broad topic, and many of its subareas, such as X-ray crystallography, are themselves important scientific topics. Crystallography ranges from the fundamentals of crystal structure to the mathematics of crystal geometry, including those that are not periodic or quasicrystals. At the atomic scale it can involve the use of X-ray diffraction to produce experimental data that the tools of X-ray crystallography can convert into detailed positions of atoms, and sometimes electron density. At larger scales it includes experimental tools such as orientational imaging to examine the relative orientations at the grain boundary in materials. Crystallography plays a key role in many areas of biology, chemistry, and physics, as well as in emerging developments in these fields. (Full article...) -

Image 20Halite from the Wieliczka salt mine, Małopolskie, Poland

Halite (/ˈhælaɪt, ˈheɪlaɪt/ HAL-yte, HAY-lyte), commonly known as rock salt, is a type of salt, the mineral (natural) form of sodium chloride (NaCl). Halite forms isometric crystals. The mineral is typically colorless or white, but may also be light blue, dark blue, purple, pink, red, orange, yellow or gray depending on inclusion of other materials, impurities, and structural or isotopic abnormalities in the crystals. It commonly occurs with other evaporite deposit minerals such as several of the sulfates, halides, and borates. The name halite is derived from the Ancient Greek word for "salt", ἅλς (háls). (Full article...) -

Image 21

Amethyst is a violet variety of quartz. The name comes from the Koine Greek αμέθυστος amethystos from α- a-, "not" and μεθύσκω (Ancient Greek) methysko / μεθώ metho (Modern Greek), "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that the stone protected its owner from drunkenness. Ancient Greeks wore amethyst and carved drinking vessels from it in the belief that it would prevent intoxication.

Amethyst, a semiprecious stone, is often used in jewelry.

It occurs mostly in association with calcite, quartz, smoky quartz, hematite, pyrite, fluorite, goethite, agate, and chalcedony. (Full article...) -

Image 22

Crystal structure of table salt (sodium in purple, chlorine in green)

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat along the principal directions of three-dimensional space in matter.

The smallest group of particles in a material that constitutes this repeating pattern is the unit cell of the structure. The unit cell completely reflects the symmetry and structure of the entire crystal, which is built up by repetitive translation of the unit cell along its principal axes. The translation vectors define the nodes of the Bravais lattice.

The lengths of principal axes/edges, of the unit cell and angles between them are lattice constants, also called lattice parameters or cell parameters. The symmetry properties of a crystal are described by the concept of space groups. All possible symmetric arrangements of particles in three-dimensional space may be described by 230 space groups.

The crystal structure and symmetry play a critical role in determining many physical properties, such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical transparency. (Full article...) -

Image 23

Borax (also referred to as sodium borate, tincal (/ˈtɪŋkəl/) and tincar (/ˈtɪŋkər/)) is a salt (ionic compound) normally encountered as a hydrated borate of sodium, with the chemical formula Na2H20B4O17. Borax mineral is a crystalline borate mineral that occurs in only a few places worldwide in quantities that enable it to be mined economically.

Borax can be dehydrated by heating into other forms with less water of hydration. The anhydrous form of borax can also be obtained from the decahydrate or other hydrates by heating and then grinding the resulting glasslike solid into a powder. It is a white crystalline solid that dissolves in water to make a basic solution due to the tetraborate anion.

Borax is commonly available in powder or granular form and has many industrial and household uses, including as a pesticide, as a metal soldering flux, as a component of glass, enamel, and pottery glazes, for tanning of skins and hides, for artificial aging of wood, as a preservative against wood fungus, as a food additive, and as a pharmaceutic alkalizer. In chemical laboratories it is used as a buffering agent.

The terms tincal and tincar refer to the naturally occurring borax historically mined from dry lake beds in various parts of Asia. (Full article...) -

Image 24Cinnabar, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Germany

Cinnabar (/ˈsɪnəˌbɑːr/; from Ancient Greek κιννάβαρι (kinnábari)), also called cinnabarite (/ˌsɪnəˈbɑːraɪt/) or mercurblende, is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining elemental mercury and is the historic source for the brilliant red or scarlet pigment termed vermilion and associated red mercury pigments.

Cinnabar generally occurs as a vein-filling mineral associated with volcanic activity and alkaline hot springs. The mineral resembles quartz in symmetry and it exhibits birefringence. Cinnabar has a mean refractive index near 3.2, a hardness between 2.0 and 2.5, and a specific gravity of approximately 8.1. The color and properties derive from a structure that is a hexagonal crystalline lattice belonging to the trigonal crystal system, crystals that sometimes exhibit twinning.

Cinnabar has been used for its color since antiquity in the Near East, including as a rouge-type cosmetic, in the New World since the Olmec culture, and in China since as early as the Yangshao culture, where it was used in coloring stoneware. In Roman times, cinnabar was highly valued as paint for walls, especially interiors, since it darkened when used outdoors due to exposure to sunlight.

Associated modern precautions for the use and handling of cinnabar arise from the toxicity of the mercury component, which was recognized as early as ancient Rome. (Full article...) -

Image 25A ruby crystal from Dodoma Region, Tanzania

Ruby is a pinkish-red to blood-red gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum (aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires; given that the rest of the corundum species are called as such, rubies are sometimes referred to as "red sapphires".

Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, alongside amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the presence of chromium.

Some gemstones that are popularly or historically called rubies, such as the Black Prince's Ruby in the British Imperial State Crown, are actually spinels. These were once known as "Balas rubies".

The quality of a ruby is determined by its color, cut, and clarity, which, along with carat weight, affect its value. The brightest and most valuable shade of red, called blood-red or pigeon blood, commands a large premium over other rubies of similar quality. After color comes clarity: similar to diamonds, a clear stone will command a premium, but a ruby without any needle-like rutile inclusions may indicate that the stone has been treated. Ruby is the traditional birthstone for July and is usually pinker than garnet, although some rhodolite garnets have a similar pinkish hue to most rubies. The world's most valuable ruby to be sold at auction is the Estrela de Fura, which sold for US$34.8 million. (Full article...)

Selected mineralogist

-

Image 1Charles Anderson (5 December 1876, Stenness – 25 October 1944 Darlinghurst, New South Wales) was an Australian mineralogist and palaeontologist. He was director of the Australian Museum from 1921 to 1940. (Full article...)

-

Image 2

Ignacy Domeyko or Domejko, pseudonym: Żegota (Spanish: Ignacio Domeyko, Spanish pronunciation: [iɣˈnasjo ðoˈmejko]; 31 July 1802 – 23 January 1889) was a Polish geologist, mineralogist, educator, and founder of the University of Santiago, in Chile. Domeyko spent most of his life, and died, in his adopted country, Chile.

After a youth passed in partitioned Poland, Domeyko participated in the Polish–Russian War 1830–31. Upon Russian victory, he was exiled, spending part of his life in France (where he had gone with a fellow Philomath, Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz) before eventually settling in Chile, whose citizen he became. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Count Lev Alekseyevich von Perovski (Russian: Лев Алексе́евич Перо́вский, also transliterated as Perofsky, Perovskii, Perovskiy, Perovsky, Perowski, and Perowsky; also credited as L.A. Perovski) (9 September 1792 – 21 November 1856) was a Russian nobleman and mineralogist who also served as Minister of Internal Affairs under Nicholas I of Russia.

In 1845, he proposed the creation of the Russian Geographical Society. (Full article...) -

Image 4Marjorie Hooker (10 May 1908 – 4 May 1976) was an American geologist who worked to collect data on the make-up of igneous and metamorphic rocks as well as acted as a mineral specialist for the United States Department of State from 1943 to 1947. Her work on deciphering chemical data for granite rocks led her to collect and correspond information with geologists from all around the world. The multiple associations with which she worked include the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Washington Academy of Sciences, the Geological Society of London, the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the American Geophysical Union, the Geological Society of America, and the Mineralogical Association of Canada. She also worked as a delegate of the International Geological Congresses for their 19th, 20th, 23rd, and 24th meetings. Her contributions to Geology have been recognized with an award created in her name at Syracuse University to recognize and aid exceptional student research. (Full article...)

-

Image 5Vesselina Vassileva Breskovska (Bulgarian: Веселина Василева Бресковска) (December 6, 1928, Granit, Stara Zagora Province, Bulgaria – August 12, 1997, Sofia, Bulgaria) was a 20th-century Bulgarian geologist, mineralogist and crystallographer. (Full article...)

-

Image 6

George Frederick Kunz (September 29, 1856 – June 29, 1932) was an American mineralogist and mineral collector. (Full article...) -

Image 7

Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 1770 – 7 October 1847) was a French chemist, mineralogist, geologist, paleontologist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris. Observing fossil content as well as lithology in sequences, he classified Tertiary formations and was responsible for defining 19th century geological studies as a subject of science by assembling observations and classifications.

Brongniart was also the founder of the Musée national de Céramique-Sèvres (National Museum of Ceramics), having been director of the Sèvres Porcelain Factory from 1800 to 1847. (Full article...) -

Image 8

Alphonse Renard by Alphonse de Tombay (Brussels) - September 2019

Alphonse Francois Renard (27 September 1842 – 9 July 1903), Belgian geologist and petrographer, was born at Ronse, in East Flanders, on 27 September 1842. He was educated for the church of Rome, and from 1866 to 1869 he was superintendent at the college de la Paix, Namur.

In 1870 he entered the Jesuit Training College at the old abbey of Maria Laach in the Eifel, and there, while engaged in studying philosophy and science, he became interested in the geology of the district, and especially in the volcanic rocks. Thenceforth he worked at chemistry and mineralogy, and qualified himself for those petrographical researches for which he was distinguished. (Full article...) -

Image 9Erika Pohl-Ströher (18 January 1919 – 18 December 2016) was a German business executive, heiress, and collector of minerals and German folk art. She was resident in Switzerland for much of her life. (Full article...)

-

Image 10Frederick Eugene Wright (October 16, 1877 – August 25, 1953) was an American optical scientist and geophysicist. He was the second president of the Optical Society of America from 1918-1919. (Full article...)

-

Image 11Hatten Schuyler Yoder, Jr., (March 20, 1921 – August 2, 2003) was an American geophysicist and experimental petrologist who conducted pioneering work on minerals under high pressure and temperature. He was noted for his study of silicates and igneous rocks. (Full article...)

-

Image 12

William Walter Jefferis (January 12, 1820 – February 23, 1906) was an American mineralogist and curator of the William S. Vaux Collection of minerals and artifacts at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences from 1883 to 1898. He personally collected and cataloged 35,000 mineral specimens, which he sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1905. (Full article...) -

Image 13

Nikolai Ivanovich Koksharov

Nikolai Ivanovich Koksharov (Russian: Николай Иванович Кокшаров) (23 November (5 December), 1818 – 21 December (2 January), 1893) was a Russian mineralogist, crystallographer, and major general in the Russian army. He was noted for his measurements of crystals using a goniometer. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Karl Cäsar von Leonhard (12 September 1779 – 23 January 1862) was a German mineralogist and geologist. His son, Gustav von Leonhard, was also a mineralogist.

From 1797 he studied at the universities of Marburg and Göttingen, where Johann Friedrich Blumenbach was an important influence to his career. He collected many mineralogical specimens on scientific excursions in Saxony and Thuringia, continued by travel to the Austrian Alps (including the Salzkammergut). During his journeys he made the acquaintance of Friedrich Mohs and Karl von Moll. In 1818, through assistance from Baden minister of state Sigismund von Reitzenstein, he was appointed professor of mineralogy at the University of Heidelberg. (Full article...) -

Image 15

Charles Friedel (French: [ʃaʁl fʁidɛl]; 12 March 1832 – 20 April 1899) was a French chemist and mineralogist. (Full article...) -

Image 16William Sansom Vaux (May 19, 1811 – May 5, 1882) was an American mineralogist. He served as vice-president of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia from 1864 to 1882 and as president of the Zoological Society of Philadelphia. His mineral and archaeological collections were bequeathed to the Academy of Natural Sciences after his death. (Full article...)

-

Image 17Werner Schreyer (14 November 1930 in Nuremberg; 12 February 2006 in Bochum) was a German mineralogist and experimental metamorphic petrologist. Schreyer completed his undergraduate work in geology and petrology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, obtained his doctorate from the University of Munich in 1957, and in 1966 received his Habilitation from the University of Kiel. He was a professor at Ruhr University Bochum from 1966 to 1996. In 2002 Schreyer became the first German to be awarded the Mineralogical Society of America's highest honor, the Roebling Medal. Schreyer was a leading expert on phase relations in the MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O (MASH) system, specializing in cordierite and minerals with equivalent chemical compositions, and high pressure and ultra high-pressure metamorphic mineral assemblages.

The mineral Schreyerite (V2Ti3O9) was named after Schreyer. (Full article...) -

Image 18William Sefton Fyfe, CC FRSC FRS FRSNZ (4 June 1927 – 11 November 2013) was a New Zealand geologist and Professor Emeritus in the department of Earth Sciences at the University of Western Ontario. He is widely considered among the world's most eminent geochemists. (Full article...)

-

Image 19

Gustav Adolph Kenngott, c. 1860

Gustav Adolph Kenngott (January 6, 1818 – March 7, 1897) was a German mineralogist. (Full article...) -

Image 20Charles Thompson Prewitt (March 3, 1933 – April 28, 2022) was an American mineralogist and solid state chemist known for his work on structural chemistry of minerals and high-pressure chemistry. (Full article...)

-

Image 21Stanley Hay Umphray Bowie FRS (born 24 March 1917, in Bixter, Shetland - died 3 September 2008) was a Scottish geologist. He was considered a "world authority on uranium geology and a leader in the field of geochemistry and mineralogy". He developed methods and tools to identify opaque minerals using micro-indentation hardness and optical reflectance. He worked for the British Geological Survey between 1946 and 1977. The mineral bowieite was so named in recognition of his work on identification of opaque minerals. (Full article...)

-

Image 22

Gustav Anton Zeuner (German: [ˈɡʊstaːf ˈʔantoːn ˈtsɔʏnɐ]; 30 November 1828 – 17 October 1907) was a German physicist, engineer, and epistemologist, considered the founder of technical thermodynamics and of the Dresden School of Thermodynamics. (Full article...) -

Image 23Charles-Victor Mauguin (French: [ʃaʁl.vik.tɔʁ mo.gɛ̃]; 19 September 1878 – 25 April 1958), more often Charles Mauguin, was a French mineralogist and crystallographer. He and Carl Hermann invented an international standard notation for crystallographic groups called Hermann–Mauguin notation (also sometimes called international notation). (Full article...)

-

Image 24

Christian Samuel Weiss (26 February 1780 – 1 October 1856) was a German mineralogist born in Leipzig.

Following graduation, he worked as a physics instructor in Leipzig from 1803 until 1808. and in the meantime, conducted geological studies of mountain formations in Tyrol, Switzerland and France (1806–08). In 1810 he became a professor of mineralogy at the University of Berlin, where in 1818/19 and 1832/33, he served as university rector. He died near Eger in Bohemia. (Full article...) -

Image 25Ernst Friedrich Glocker (1 May 1793 – 18 July 1858) was a German mineralogist, geologist, and paleontologist. (Full article...)

Related portals

Did you know...

- ... that nine days after his heart transplant, J. C. Walter Jr. merged his company Houston Oil & Minerals with Tenneco, then retired to his ranch and shortly after founded Walter Oil & Gas?

Get involved

For editor resources and to collaborate with other editors on improving Wikipedia's Minerals-related articles, see WikiProject Rocks and minerals.

General images

-

Image 2Schist is a metamorphic rock characterized by an abundance of platy minerals. In this example, the rock has prominent sillimanite porphyroblasts as large as 3 cm (1.2 in). (from Mineral)

-

Image 3Pink cubic halite (NaCl; halide class) crystals on a nahcolite matrix (NaHCO3; a carbonate, and mineral form of sodium bicarbonate, used as baking soda). (from Mineral)

-

Image 6Native gold. Rare specimen of stout crystals growing off of a central stalk, size 3.7 x 1.1 x 0.4 cm, from Venezuela. (from Mineral)

-

Image 8Black andradite, an end-member of the orthosilicate garnet group. (from Mineral)

-

Image 10Red cinnabar (HgS), a mercury ore, on dolomite. (from Mineral)

-

Image 11Hübnerite, the manganese-rich end-member of the wolframite series, with minor quartz in the background (from Mineral)

-

Image 12Asbestiform tremolite, part of the amphibole group in the inosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 13When minerals react, the products will sometimes assume the shape of the reagent; the product mineral is termed a pseudomorph of (or after) the reagent. Illustrated here is a pseudomorph of kaolinite after orthoclase. Here, the pseudomorph preserved the Carlsbad twinning common in orthoclase. (from Mineral)

-

Image 17Perfect basal cleavage as seen in biotite (black), and good cleavage seen in the matrix (pink orthoclase). (from Mineral)

-

Image 18Sphalerite crystal partially encased in calcite from the Devonian Milwaukee Formation of Wisconsin (from Mineral)

-

Image 19Mohs Scale versus Absolute Hardness (from Mineral)

-

Image 20Muscovite, a mineral species in the mica group, within the phyllosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 21Epidote often has a distinctive pistachio-green colour. (from Mineral)

-

Image 22An example of elbaite, a species of tourmaline, with distinctive colour banding. (from Mineral)

-

Image 23Diamond is the hardest natural material, and has a Mohs hardness of 10. (from Mineral)

-

Image 25Mohs hardness kit, containing one specimen of each mineral on the ten-point hardness scale (from Mohs scale)

-

Image 26Gypsum desert rose (from Mineral)

Did you know ...?

- ... that Treak Cliff Cavern (pictured) is one of only two remaining active sources of the ornamental mineral Blue John?

- ...that chalcocite, a profitable and desirable kind of copper ore, was particularly plentiful in the now-depleted copper mines of Cornwall, England and Bristol, Connecticut?

- ... that Gloria J. Romero is leading a campaign in the California Legislature to remove serpentine as the official state rock because it is a source of cancer-causing asbestos?

- ... that the mineral abelsonite probably formed from chlorophyll and is the only known crystalline geoporphyrin?

Subcategories

Topics

| Overview | ||

|---|---|---|

| Common minerals | ||

Ore minerals, mineral mixtures and ore deposits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ores |

| ||||||||

| Deposit types | |||||||||

| Borates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonates | |||||

| Oxides |

| ||||

| Phosphates | |||||

| Silicates | |||||

| Sulfides | |||||

| Other |

| ||||

| Crystalline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptocrystalline | |||||||

| Amorphous | |||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||

| Notable varieties |

| ||||||

| Oxide minerals |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate minerals | |||||

| Other | |||||

Gemmological classifications by E. Ya. Kievlenko (1980), updated | |||||||||

| Jewelry stones |

| ||||||||

| Jewelry-Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

| Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

Mineral identification | |

|---|---|

| "Special cases" ("native elements and organic minerals") |

|

|---|---|

| "Sulfides and oxides" |

|

| "Evaporites and similars" |

|

| "Mineral structures with tetrahedral units" (sulfate anion, phosphate anion, silicon, etc.) |

|

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus