Neohipparion

| Neohipparion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of N. leptode at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Subfamily: | Equinae |

| Tribe: | †Hipparionini |

| Genus: | †Neohipparion Gidley, 1903 |

| Type species | |

| Neohipparion affine (Leidy, 1869)

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

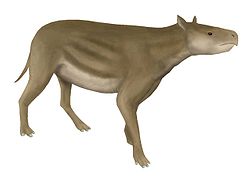

Neohipparion (Greek: "new" (neos), "pony" (hipparion)[1]) is an extinct genus of equid, from the Neogene (Miocene to Pliocene) of North America and Central America.[2][3][4]

Distribution

[edit]Fossils of this horse have been found in Texas,[5][6] Kansas,[7][8] South Dakota,[9] Montana,[10] Nevada,[11] Alabama,[12] Florida,[6][13][14] Oregon,[15] and Mexico.[16][17][18]

Description

[edit]This prehistoric species of hipparionin equid grew to lengths of up to 4.5 to 5 ft (1.4 to 1.5 m) long.[6]

Palaeoecology

[edit]Reproduction

[edit]In Florida, Neohipparion lived in a savanna environment during the dry season but moved to a wet environment when it came time to mate. The average age of death for a newborn colt was 3.5 years, with a juvenile mortality rate of 64% during its first 2 years of existence.[19]

Diet

[edit]δ13C values of N. trampasense from the Love Bone Bed of Florida show it had a clear preference for foraging in open habitats.[14] δ13C values from N. eurystyle fossils found in Florida indicate that it fed almost exclusively on C4 grasses,[20][21] while fossils of the same species from central Mexico indicate a more varied diet that consisted of both C3 and C4 plants.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ "Glossary. American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Neohipparion eurystyle". Florida Museum. 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Neohipparion". Florida Museum. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J. (1985). "Patterns of Phylogeny and Rates of Evolution in Fossil Horses: Hipparions from the Miocene and Pliocene of North America". Paleobiology. 11 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1017/S009483730001157X. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2400665. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Quinn, James Harrison (1952). "Recognition of Hipparions and other horses in the middle Miocene mammalian faunas of the Texas Gulf region". Bureau of Economic Geology – via University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ a b c Hulbert, Richard C. (July 1987). "Late Neogene Neohipparion (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Gulf Coastal Plain of Florida and Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 61 (4): 809–830. Bibcode:1987JPal...61..809H. doi:10.1017/s0022336000029152. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 130745896. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Darnell, Michelle (1 December 2000). "Systematics of the Fossil Equidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla), Minimum Quarry, Graham County, Kansas". Master's Theses. doi:10.58809/HMSW1030.

- ^ Darnell, Michelle K.; Thomasson, Joseph R. (2007). "First Equid Remains from the Late Miocene Prolithospermum johnstonii-Nassella pohlii Assemblage Zone Stratotype Locality, Ellis County, Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 110 (1/2): 10–15. ISSN 0022-8443.

- ^ Macdonald, James Reid (1960). "An Early Pliocene Fauna from Mission, South Dakota". Journal of Paleontology. 34 (5): 961–982. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1301023. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via GeoScienceWorld.

- ^ Storer, John E. (1 August 1969). "An Upper Pliocene neohipparion from the Flaxville Gravels, northern Montana". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 6 (4): 791–794. doi:10.1139/e69-076. ISSN 0008-4077. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Canadian Science Publishing.

- ^ Macdonald, James Reid (1956). "A New Clarendonian Mammalian Fauna from the Truckee Formation of Western Nevada". Journal of Paleontology. 30 (1): 186–202. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1300391.

- ^ Hulbert, Richard C.; Whitmore, Frank C. (1 June 2006). "Late Miocene mammals from the Mauvilla local fauna, Alabama". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 46 (1): 1–28. doi:10.58782/flmnh.xcpo4034. ISSN 0071-6154. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J. (1986). "Late Hemphillian Monodactyl Horses (Mammalia, Equidae) from the Bone Valley Formation of Central Florida". Journal of Paleontology. 60 (2): 466–475. doi:10.1017/S0022336000021995. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1305172. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ a b Feranec, Robert S.; MacFadden, Bruce J. (Spring 2006). "Isotopic discrimination of resource partitioning among ungulates in C 3 -dominated communities from the Miocene of Florida and California". Paleobiology. 32 (2): 191–205. doi:10.1666/05006.1. ISSN 0094-8373. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Geology of the Rattlesnake quadrangle Bearpaw Mountains, Blaine County, Montana (Report). US Geological Survey. 1964. doi:10.3133/b1181b.

- ^ a b Pérez-Crespo, Víctor Adrián; Carranza-Castañeda, Oscar; Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquín; Morales-Puente, Pedro; Cienfuegos-Alvarado, Edith; Otero, Francisco J. (1 April 2017). "Diet and habitat of unique individuals of Dinohippus mexicanus and Neohipparion eurystyle (Equidae) from the late Hemphillian (Hh3) of Guanajuato and Jalisco, central Mexico: stable isotope studies". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas. 34 (1): 38. doi:10.22201/cgeo.20072902e.2017.1.470. ISSN 2007-2902. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE GEOQUÍMICA.

- ^ Stirton, R. A. (1955). "Two New Species of the Equid Genus Neohipparion from the Middle Pliocene, Chihuahua, Mexico". Journal of Paleontology. 29 (5): 886–902. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1300411. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Lindsay, Everett H. (1984). "Late Cenozoic Mammals from Northwestern Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 4 (2): 208–215. ISSN 0272-4634. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ Hulbert, Richard C. (1982). "Population Dynamics of the Three-Toed Horse Neohipparion from the Late Miocene of Florida". Paleobiology. 8 (2): 159–167. doi:10.1017/s0094837300004504. ISSN 0094-8373. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Cambridge Core.

- ^ Clementz, M. T. (2012). "New insight from old bones: Stable isotope analysis of fossil mammals". Journal of Mammalogy. 93 (2): 368–380. doi:10.1644/11-MAMM-S-179.1. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J.; Solounias, Nikos; Cerling, Thure E. (5 February 1999). "Ancient Diets, Ecology, and Extinction of 5-Million-Year-Old Horses from Florida". Science. 283 (5403): 824–827. doi:10.1126/science.283.5403.824. ISSN 0036-8075. Retrieved 27 November 2024.