Marching Through Georgia

"Marching Through Georgia"[a] is an American Civil War-era marching song written and composed by Henry Clay Work. It is sung from the perspective of a Union soldier who had participated in Sherman's March to the Sea; he looks back on the momentous triumph after which Georgia became a "thoroughfare for freedom" and the Confederacy neared collapse.

Work made a name for himself in the Civil War for penning rousing tunes that reflected the Union's struggle and progress in the war. The music publishing house Root & Cady employed him in 1861, a post he maintained throughout the war. Following the March to the Sea, the Union's triumph that left Confederate resources in tatters and civilians in anguish, Work was inspired to write a commemorative tune, "Marching Through Georgia".

The song was released in January 1865 to widespread success. One of the few Civil War compositions that withstood the war's end, it cemented a place in veteran reunions and marching parades. Sherman, to whom the song is dedicated, famously grew to despise it after being repeatedly subjected to its strains at the public gatherings he attended. "Marching Through Georgia" lent its tune to numerous partisan hymns, such as "Billy Boys" and "The Land". Beyond the United States, troops across the world have adopted it as a marching standard, from the Japanese in the Russo–Japanese War to the British in World War Two.

Background

[edit]Work as a songwriter

[edit]

Henry Clay Work (1832–1884) was a printer by trade.[1] However, his true passion rested in music, a passion that blossomed during his youth and drew him into songwriting.[2] He published a song for the first time in 1853,[3] and eight years later, when the American Civil War broke out,[4] his musical efforts took on a new life.[b] Work promptly approached the Chicagoan music publishing firm Root & Cady, presenting its publishing director George F. Root[7] with a manuscript of "Kingdom Coming". Root was impressed and assigned him a post.[8][c]

Throughout the Civil War, music bore great importance,[10] as the musicologist Irwin Silber comments: "soldiers and civilians of the Union states were inspired and propagandized by a host of patriotic songs."[11] Work, a Northerner, delivered,[12] penning 29 songs from 1861 to 1865.[13] His songs have been noted for communicating the feelings of Union civilians,[14] perhaps more so than "[those of] … any other songwriter," writes The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.[15] Some of Work's wartime compositions also impart anti-slavery sentiments, stemming from his upbringing on the Underground Railroad.[16]

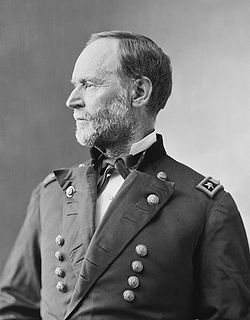

"Marching Through Georgia" would prove his most fruitful work yet.[17] Released c. January 9, 1865,[18] it commemorates the March to the Sea, a momentous Union triumph that had taken place a few weeks prior.[19] The song is dedicated to the campaign's mastermind, Major General William T. Sherman.[20] While other contemporary songs honored the march, such as H. M. Higgins' "General Sherman and His Boys in Blue" and S. T. Gordon's "Sherman's March to the Sea", Work's composition remains the best known.[21]

March to the Sea

[edit]

By September 1864, the Union looked set to win the Civil War. Sherman, who had just captured Atlanta,[22] decided to pursue the coastal city of Savannah[23] with an assembled unit of 62,000 troops. On November 15, they left Atlanta to commence the March to the Sea.[24] Progress was smooth.[25] After a series of minor skirmishes and just two notable engagements at Griswoldville and Fort McAllister, the Union army moved into Savannah on December 21, which concluded the march.[26]

Sherman's campaign bore two immediate impacts on the South. Firstly, troops left destruction and paucity in their tracks as they scavenged the land for food and resources and laid waste to public buildings and infrastructure.[27] This fit Sherman's strategy—to persuade Southerners that the war was not worth supporting anymore.[28] Secondly, it inspired Southern slaves to flee to freedom. Over 14,000 joined the Union troops in Georgia with brisk enthusiasm once they passed near their native plantation, cementing the campaign as a milestone of emancipation.[29]

A pioneering use of psychological warfare and total war,[30] the destruction wrought by Sherman's troops terrorized the South. Civilians whose territory and resources were ravaged grew so appalled at the conflict that their will to fight on dissipated, as Sherman had intended.[31] The march further crippled the Southern economy, incurring losses of approximately $100 million.[32][d] In the historian Herman Hattaway's words, it "[knocked] the Confederate war effort to pieces."[34]

Composition

[edit]Lyrical analysis

[edit]

Bring the good old bugle boys! we'll sing another song,

Sing it with a spirit that will start the world along;

Sing it as we used to sing it fifty thousand strong,

While we were marching through Georgia.

CHORUS

"Hurrah! Hurrah! we bring the Jubilee!

Hurrah! Hurrah! the flag that makes you free!"

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

How the darkeys shouted when they heard the joyful sound!

How the turkeys gobbled which our commissary found!

How the sweet potatoes even started from the ground,

While we were marching through Georgia.

(CHORUS)

Yes, and there were Union men who wept with joyful tears,

When they saw the honor'd flag they had not seen for years;

Hardly could they be restrained from breaking forth in cheers,

While we were marching through Georgia.

(CHORUS)

"Sherman's dashing Yankee boys will never reach the coast!"

So the saucy rebels said, and 'twas a handsome boast,

Had they not forgot, alas! to reckon with the host,

While we were marching through Georgia.

(CHORUS)

So we made a thoroughfare for Freedom and her train,

Sixty miles in latitude—three hundred to the main;

Treason fled before us for resistance was in vain,

While we were marching through Georgia.

(CHORUS)

"Marching Through Georgia" is sung from a Union soldier's point of view. He had taken part in the March to the Sea and now recounts the campaign's triumphs and their repercussions on the Confederacy.[36] The song comprises five stanzas and a refrain.[37]

The first stanza commences with a rallying cry for Sherman's troops.[37] As notes the historian David J. Eicher, it underrepresents their number as 50,000; in fact, over 60,000 took part in the march.[38] The chorus symbolizes the end of African-American servitude and the advent of a new life of freedom; it renders the war an effort in emancipation above all else.[39] A retelling of Southern Unionists' celebration of the Northern troops defines the third stanza:[39] they "[weep] with joyful tears / When they [see] the honor'd flag they had not seen for years."[40] A comedic tone is imbued in the fourth stanza, where the Confederates who had scoffed at Sherman's campaign see themseves proven wrong.[37] The final stanza celebrates the success of the march,[37] after which "treason fled before [the Union troops] for resistance was in vain".[41]

The historian Christian McWhirter evaluates the song's lyrical and thematic framework:

On the surface, it celebrated Sherman's campaign from Atlanta to Savannah; but it also told listeners how to interpret Union victory. Speaking as a white soldier, Work turned the targeting of Confederate civilian property into a celebration of unionism and emancipation. Instead of destroyers, Union soldiers became deliverers for slaves and southern unionists. Georgia was not left in ruins but was converted into 'a thoroughfare for freedom.'[42]

Musical analysis

[edit]"Marching Through Georgia" is in common time in the key of B♭ major. It commences with a four-bar introduction which follows a chord progression of B♭–E♭–B♭–F7–B♭. Each verse and chorus is eight bars long. A soloist is intended to sing the individual stanzas, and a joint SATB choir accompanies the solo voice for the chorus. Work does not write any expression markings or dynamics throughout the song, bar a fortissimo marking at the start of the chorus. The original sheet music provides a piano accompaniment to be performed during the song.[43] According to Florine Thayer McCray, the song's "suggestive verse" and "swinging meter" capture the enthusiasm felt by Union troops during the campaign.[44]

General analysis

[edit]Like other pieces in Work's wartime catalog,[14] "Marching Through Georgia" captures contemporary attitudes among Northern civilians—in this case, jubilation over Sherman's fruitful campaign. It fulfilled their demand for a celebratory patriotic hymn.[39] Accordingly, the song imparts patriotic spirit,[45] such that it "rubbed Yankee salt into one of the sorest wounds of the Civil War," in the musicologist Sigmund Spaeth's words.[46] To soldiers, Work's piece was the "only [one] which [...] thoroughly expressed their triumphant enthusiasm," according to McWhirter.[47]

"Marching Through Georgia" was one of the few wartime compositions to outlast the conflict.[48] Civilians had grown tired of war, mirrored by the short-lasting fame of "Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!", an anthem known to the entire Union that nonetheless left the spotlight after 1865.[49] In his autobiography published 26 years after Work drafted the song, George F. Root explains its unique postbellum popularity:

[It] is more played and sung at the present time than any other song of the war. This is not only on account of the intrinsic merit of its words and music, but because it is retrospective. Other war songs, "The Battle Cry of Freedom" for example, were for exciting the patriotic feeling on going in to the war or the battle; "Marching Through Georgia" is a glorious remembrance on coming triumphantly out, and so has been more appropriate to soldiers' and other gatherings ever since.[50]

Legacy

[edit]Postbellum

[edit]

"Marching Through Georgia" cemented itself as a Civil War icon.[51] It came to the define the March to the Sea[38] and became Sherman's unofficial theme song.[52] Selling 500,000 copies of sheet music within 12 years,[53] it was one of the most successful wartime tunes and Work's most profitable hit up to that point.[54] David Ewen regards it as "the greatest of his war songs,"[55] and Carl S. Lowden deems it his very best work, in part owing to its "soul-stirring" production and longevity.[56]

Edwin Tribble opines that Work's postbellum fame, the little he had, rested on the success of "Marching Through Georgia",[57] citing a letter he wrote to his long-time correspondent Susie Mitchell: "It is really surprising that I have excited so much curiosity and interest here [at an annual encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR)], not only among romantic young women but among all classes. My connection with 'Marching Through Georgia' seems to be the cause."[58][e] In fact, starting from the late nineteenth century, the song predominated Northern veteran gatherings.[60]

Sherman himself came to loathe "Marching Through Georgia" because of its ubiquity in the North, being performed unremittingly at public functions he attended. When he reviewed the national encampment of the GAR in 1890, the hundreds of bands present played the tune every time they passed him for an unbroken seven hours.[61] Eyewitnesses claim that "his patience collapsed and he declared that he would never again attend another encampment until every band in the United States had signed an agreement not to play 'Marching Though Georgia' in his presence."[62] Sherman maintained his promise for all his life. However, the song was played at his funeral.[63]

"Marching Through Georgia" does not share the same popularity in the nation's other half. Irwin Silber deems it the most despised Unionist song in the South owing to its evoking a devastated Georgia at the hands of Sherman's army.[64] Accordingly, Sigmund Spaeth explicitly advises readers not to sing or play Work's composition to a Southerner.[65] Two incidents, both at a Democratic National Convention, exemplify Georgia's contempt for the song. In the 1908 convention, Georgia was one of the few states not to send its delegates[66] to the eventual victor William Jennings Bryan;[67] the band insultingly played "Marching Through Georgia" to express the convention's disapproval.[66] A similar incident sparked in 1924. When tasked to play a fitting song for the Georgia delegation, the convention's band broke into Work's piece.[68] The historian John Tasker Howard remarks: "[...] when the misguided leader, stronger on geography than history, swung into Marching Through Georgia, he was greeted by a silence that turned into hisses and boos noisier than the applause he had heard before."[69]

Military and nationalist uses

[edit]While "undeniably" American,[70] "Marching Through Georgia" has become a "universal anthem."[71] Armed forces across the world have performed it:[53] Japanese troops sang "Marching Through Georgia" as they entered Port Arthur at the Russo–Japanese War's onset, and British troops stationed in India periodically chanted it.[72] The song's melody has also been adapted into numerous regional military and nationalist anthems. The Princeton football fight song "Nassau! Nassau!" borrowed the melody of Work's piece,[73] as did the controversial pro-Ulster hymn "Billy Boys",[74] whose chorus goes:

Political uses

[edit]Both major candidates in the 1896 U.S. presidential election, William McKinley and William Jennings Bryan, featured songs sung to the tune of "Marching Through Georgia" in their campaign.[76] The melody of "Paint 'Er Red", a pro-labor tune of the Industrial Workers of the World, is based on the song.[77] In the United Kingdom, the song lent the tune of future prime minister David Lloyd George's campaign song "George and Gladstone"[78] as well as the liberal anthem, "The Land". The latter is a Georgist protest song calling for the fair distribution of land:[79]

The land! the land! 'twas God who gave the land!

The land! the land! the ground on which we stand!

Why should we be beggars, with the ballot in our hand?

"God gave the land to the People!"[80]

Other uses

[edit]Several films have employed Work's piece. Some carpetbaggers in the epic Gone with the Wind (1939) chants its chorus while trying to steal Tara from Scarlett O'Hara.[52] The western Shane (1953) features the song, again, "making sport of a Rebel character."[81] "Marching Through Georgia" was additionally incorporated in Ken Burns' documentary The Civil War (1990) and Charles Ives' orchestral suite Three Places in New England.[37]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes spelled "Marching Thru' Georgia" or "Marching Thro Georgia".

- ^ The New Grove Dictionary notes that the American Civil War "seeded his most fecund songwriting period",[5] and David S. Hill observes that "it was only until the tremendous success of his first war song … that he began to take his composing seriously."[6]

- ^ However, it was "Brave Boys Are They", and earlier piece, that secured Work's contract with Root & Cady, although Work presented it to Root after "Kingdom Coming".[9]

- ^ Roughly equating to $2 billion as of 2025.[33]

- ^ In spite of this, Work would enjoy another major success in 1876 with "Grandfather's Clock".[59]

Citations

[edit]- ^

- Hill, "The Mysterious Chord", 215–216

- Tome, "Marching Through Georgia"

- ^

- Birdseye, "America's Song Composers", 284–285

- Howard, Our American Music, 267

- ^ Hill, "The Mysterious Chord", 213, 216

- ^

- Carder, George F. Root, 101

- Kennedy, Civil War Battlefield Guide, 1

- ^ Sadie & Tyrrell, New Grove Dictionary, 568

- ^ Hill, "The Mysterious Chord", 216

- ^

- Carder, George F. Root, 86, 114

- Epstein, "Music Publishing in Chicago", 43, 46

- ^ Carder, George F. Root, 114

- ^

- Hill, "The Mysterious Chord", 216

- Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 425

- ^

- Kelley & Snell, Bugle Resounding, 13

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 12–15

- Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 7–8

- ^ quoted in Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 7

- ^

- Howard, Our American Music, 266–267

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 20, 146–147

- ^ Kelley & Snell, Bugle Resounding, 121

- ^ a b

- McCray, "About Henry Clay Work", 10

- Spaeth, History of Popular Music in America, 156

- ^ quoted in Sadie & Tyrrell, New Grove Dictionary, 568

- ^

- Carder, George F. Root, 114

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 146–147

- ^

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- Spaeth, History of Popular Music, 156

- ^ Hill, "The Mysterious Chord", 214

- ^

- Howard, Our American Music, 266

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 15

- ^ Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 426

- ^ Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 16, 238

- ^

- Davis, "Atlanta Campaign"

- Hattaway, How the North Won, 624–625

- ^

- Bailey, "Sherman's March to the Sea" § Preparation

- Hattaway, How the North Won, 634, 638

- Rhodes, "Sherman's March to the Sea", 466

- ^

- Eicher, The Longest Night, 761–762

- Hattaway, How the North Won, 642

- ^

- Eicher, The Longest Night, 762

- Marzalek, "Sherman's March to the Sea"

- ^

- Bailey, "Sherman's March to the Sea" § Lead, Military Encounters

- Marzalek, "Sherman's March to the Sea"

- ^

- Bailey, "Sherman's March to the Sea" § Consequences of the March

- Eicher, The Longest Night, 768

- Hattaway, How the North Won, 642

- ^ Hattaway, How the North Won, 641–642

- ^

- Drago, "How Sherman's March Affected the Slaves", 362–363

- Rhodes, "Sherman's March to the Sea", 473

- ^ Merzalek, "Sherman's March to the Sea"

- ^

- Bailey, "Sherman's March to the Sea" § Consequences of the March

- Eicher, The Longest Night, 768

- Hattaway, How the North Won, 642

- ^

- Rhodes, "Sherman's March to the Sea", 472

- Sellers, "Economic Incidence of the Civil War", 179

- ^ Webster, "Inflation Calculator"

- ^

- quoted in Hattaway, How the North Won, 655

- see also: Rhodes, "Sherman's March to the Sea", 471

- ^ Work, Songs, 18–20

- ^

- Carder, George F. Root, 153

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- ^ a b c d e Tome, "Marching Through Georgia"

- ^ a b Eicher, The Longest Night, 763

- ^ a b c McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- ^ Work, Songs, 18–19

- ^ Work, Songs, 19

- ^ quoted in McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- ^

- Tome, "Marching Through Georgia"

- Work, Songs, 18–20

- ^ McCray, "About Henry Clay Work", 10

- ^ Carder, George F. Root, 153

- ^

- quoted in Spaeth, History of Popular Music, 157

- see also: Howard, Our American Music, 266

- ^ quoted in McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- ^

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 16

- ^

- McWhirter, Battle Hymns, 169

- Root, Story of a Musical Life, 151–152

- ^ quoted in Root, Story of a Musical Life, 138

- ^ Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 7

- ^ a b Ivey, "War Is Marching Our Way"

- ^ a b

- Tome, "Marching Through Georgia"

- Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 423

- ^

- Birdseye, "America's Song Composers", 285

- McWhirter, "Battle Hymns", 169

- ^ quoted in Ewen, Popular American Composers, 188

- ^ quoted in Lowden, "Stories of Old Home Songs", 9

- ^ Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 426–428

- ^ quoted in Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 428

- ^

- Birdseye, "America's Song Composers", 286

- Ewen, "Popular American Composers", 189

- ^ Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 428

- ^

- Erbsen, Rousing Songs, 51

- Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 428

- ^ quoted in Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 428

- ^

- Erbsen, Rousing Songs, 51

- Ivey, "War Is Marching Our Way"

- ^ Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 16

- ^ Spaeth, History of Popular Music, 156

- ^ a b

- Dolan, "News and Views", 13

- Watson, "Editorial Notes", 12

- ^ Steinle, "Shall the People Rule?"

- ^ Howard, Our American Music, 266–267

- ^ quoted in Howard, Our American Music, 267

- ^ quoted in Silber, Songs of the Civil War, 4

- ^ quoted in Eicher, The Longest Night, 763

- ^

- Eicher, The Longest Night, 763

- Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 423

- ^

- Spaeth, History of Popular Music, 157

- Tribble, "Marching Through Georgia", 423

- ^ BBC, "Irish FA Bans 'Billy Boys'"

- ^ BBC, "The Bitter Divide"

- ^ Harpine, "We Want Yer, McKinley", 78–80

- ^ Green et al., Big Red Songbook, 156–157

- ^ Creiger, Bounder from Wales, 35–36

- ^ Whitehead, "God Gave the Land to the People"

- ^ Foner, American Labor Songs, 261

- ^ quoted in Ivey, "War Is Marching Our Way"

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Carder, P. H. (2008). George F. Root, Civil War Songwriter: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-3374-2.

- Creiger, Wayne (1976). Bounder from Wales. Columbia, Missouri; London, England: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0203-9.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Erbsen, Wayne (2000). Rousing Songs and True Tales of the Civil War. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications. ISBN 978-1-883206-33-8.

- Ewen, David (1962). Popular American Composers from Revolutionary Times to the Present: A Biographical and Critical Guide. New York City, New York: H. W. Wilson Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0824200404.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Foner, Philip S. (1975). American Labor Songs of the Nineteenth Century. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00187-7.

- Green, Archie; Roediger, David; Rosemont, Franklin; Salerno, Salvatore, eds. (2016). Big Red Songbook. Chicago, Illinois: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-62963-129-5.

- Hattaway, Herman; Jones, Arthur (1991). How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War (2 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06210-8.

- Howard, John T. (1946). Our American Music: Three Hundred Years of It (3rd ed.). New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. OCLC 423103.

- Kelley, Bruce C.; Snell, Mark A. (2004). Bugle Resounding: Music and Musicians of the Civil War Era. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1538-6.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2 ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- McWhirter, Christian (2012). Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3550-0.

- Root, George F. (1891). The Story of a Musical Life: An Autobiography by Geo F. Root. Cincinnati, Ohio: The John Church Co. ISBN 978-1-4047-8329-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 27 (6 ed.). New York City, New York: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-56159-239-0.

- Silber, Irwin (1995). Songs of the Civil War. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28438-7.

- Spaeth, Sigmund (1948). A History of Popular Music in America. New York: Random House.

- Work, Henry C. (n.d.). Work, Bertram G. (ed.). Songs of Henry Clay Work. New York City, New York: Little & Ives.

Studies and journals

[edit]- Birdseye, George (1879). "America's Song Composers: IV. Henry Clay Work". Potter's American Monthly. 12 (88): 284–288 – via Internet Archive.

- Drago, Edmund L. (1973). "How Sherman's March Through Georgia Affected the Slaves". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 57 (3): 361–375. JSTOR 40579903.

- Epstein, Dena J. (1944). "Music Publishing in Chicago before 1871: The Firm of Root & Cady, 1858-1871". Notes. 1 (4): 43–59. doi:10.2307/891291. JSTOR 891291.

- Harpine, William D. (2004). "'We Want Yer, McKinley': Epideictic Rhetoric in Songs from the 1896 Presidential Campaign". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 34 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1080/02773940409391274. JSTOR 40232421.

- Hill, Richard S. (1953). "The Mysterious Chord of Henry Clay Work". Notes. 10 (2): 211–225. doi:10.2307/892874. JSTOR 892874.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1901). "Sherman's March to the Sea". The American Historical Review. 6 (3): 466–474. doi:10.2307/1833511. JSTOR 1833511.

- Sellers, James L. (1927). "The Economic Incidence of the Civil War in the South". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 14 (2): 179–191. doi:10.2307/1895946. JSTOR 1895946.

- Steinle, John (2008). "'Shall the People Rule?': Denver Hosts the Democrats, 1908". Colorado Heritage Magazine. 28 (3). Archived from the original on April 27, 2024 – via Colorado Encyclopedia.

- Tribble, Edwin (1967). "'Marching Through Georgia'". The Georgia Review. 21 (4): 423–429. JSTOR 41396391.

News articles

[edit]- Dolan, Tom (July 16, 1908). "News and Views of Things: 'Marching Through Georgia!'". The Jeffersonian. p. 13. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Ivey, David. "War is Marching Our Way: The General Hated His Theme Song". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Lowden, Carl S. (August 7, 1920). "Stories of Old Home Songs: Marching Through Georgia". Dearborn Independent. p. 9. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- McCray, Florine Thayer (January 19, 1898). "About Henry Clay Work". New Haven Morning Journal and Courier. p. 10. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Watson, J. D. (October 29, 1908). "Editorial Notes". The Jeffersonian. p. 12. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- "Irish FA bans 'Billy Boys' song for Linfield fans". BBC Sport. April 16, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- "The bitter divide". BBC News. June 2, 1999. Archived from the original on November 1, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

Websites

[edit]- Bailey, Anne J. (2020). "Sherman's March to the Sea". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 19, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Davis, Stephen (2018). "Atlanta Campaign". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 10, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Marzalek, John F. (2021). "Sherman's March to the Sea". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on October 8, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Tome, Vanessa P. (2021). "'Marching through Georgia'". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 8, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Webster, Ian (October 17, 2025). "Inflation Calculator". CPI Inflation Calculator. Archived from the original on July 1, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

- Whitehead, Andrew (May 1, 2011). "God Gave the Land to the People: the Liberal 'Land Song'". History Workshop. Archived from the original on September 30, 2025. Retrieved November 1, 2025.

External links

[edit]General

[edit]- Commentary on "Marching Through Georgia" by Kelley L. Ross – via the Internet Archive

- Sheet music of "Marching Through Georgia" by Sheet Music Singer.

- Additional information on Sherman's March to the Sea on the American Battlefield Trust.

Recordings

[edit]- Recording by Tennessee Ernie Ford on his 1961 album Songs of the Civil War.

- Recording by the 97th Regimental String Band on their 1990 album Battlefields and Campfires: Civil War Era Songs, Vol. I.

- Recording by Jon English on his 2002 album Over There: Songs From America's Wars.

- Instrumental by the U.S. Marine Band on their 2011 album The Heritage of John Philip Sousa: Volume 7.

- Piano instrumental by Forte Republic as part of their series of piano renditions of Civil War songs.