Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy

| Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy | |

|---|---|

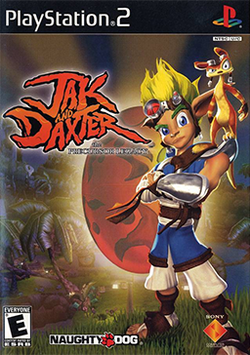

North American cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Naughty Dog |

| Publisher(s) | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Director(s) | Jason Rubin |

| Designer(s) | Evan Wells |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | |

| Composer(s) | Josh Mancell |

| Series | Jak and Daxter |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 2 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy is a 2001 platform video game developed by Naughty Dog and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation 2 (PS2). The player controls Jak, who sets out to reverse the transformation of his friend Daxter into an "ottsel", a fictional hybrid of an otter and a weasel. This quest eventually turns into an effort to stop a rogue sage from corrupting the world. The game takes place in a cohesive and non-linear world, allowing the player to freely explore interconnected areas.

The game was conceived during development of Crash Team Racing (1999), Naughty Dog's final Crash Bandicoot title. Pursuing a new intellectual property, the company envisioned a seamless 3D action-adventure that leveraged the PS2's capabilities. Development involved building a new engine using Game Oriented Assembly Lisp (GOAL), a custom language for real-time code changes, as well as recruiting animators from Disney and Nickelodeon. Naughty Dog was acquired by Sony during production, providing financial stability. Public anticipation for the game was high prior to its unveiling at E3 2001, where its title was revealed.

Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy was critically acclaimed upon release. Reviewers lauded the game's visuals and technical achievements, particularly its open seamless world devoid of load times, which were said to set a new standard for platformers. Praise also went to its gameplay polish, controls, sound effects, and voice acting. Reactions to the music and difficulty were mixed, and criticisms were directed toward the gameplay's lack of innovation, lack of bosses, simplistic story, and short length. By 2002, the game had sold over one million copies worldwide, and by 2007, it had sold two million copies in the United States alone. It is the first installment in the Jak and Daxter series, with the first sequel, Jak II, being released in 2003. A remastered version was released as part of the Jak and Daxter Collection in 2012.

Gameplay

[edit]

Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy is an open world 3D platformer with elements of action-adventure.[1] The player controls Jak, who must collect Power Cells to progress through the game's world and ultimately reach the sage Gol in the hope of reversing his friend Daxter's transformation into an ottsel (a fictitious crossbreed between an otter and a weasel).[2][3] The game's world is cohesive and non-linear, allowing free exploration across interconnected areas.[2][4]

Jak's basic actions include running, jumping, double-jumping, crouching, and ledge-grabbing.[5] Jak can also perform a rolling jump to reach distant platforms.[6][7] Jak's combat moves include a spin attack, a dash-punch, a dive attack, and an uppercut.[8] Jak has unlimited lives and three hit points, which are depleted by enemy attacks or contact with environmental hazards. Losing all three hit points triggers a death animation and a comment from Daxter before the player respawns in the beginning of the last section of the area they were located in.[6][9] Scattered throughout each area is a magical and powerful substance known as "Eco", which comes in a variety of colors and affects Jak or the environment in special ways. Green Eco restores health; Blue Eco boosts speed, activates platforms, and attracts items; Red Eco increases attack power and range; and Yellow Eco enables fireball attacks to defeat enemies or break obstacles.[1][2][3] In some sections, Jak pilots an A-GraV Zoomer (a hovercraft for races and traversal) and rides a Flut Flut bird to reach high or distant areas.[10][11]

Power Cells, the game's primary collectible, are earned by completing tasks, defeating bosses, or finding them in the environment.[3] Power Cells power the A-GraV Zoomer, which is used to traverse long passes that link certain areas together.[3][12] Precursor Orbs are the setting's currency and can be traded for Power Cells with villagers or ancient statues.[3] Each area includes seven Scout Flies, and a Power Cell is rewarded when all Scout Flies in an area are collected.[6][9] Some of the various missions that reward Power Cells include platforming challenges (such as reaching a high structure), minigames (such as fishing), races, and fetch quests.[1][9][12] The player's actions in completing tasks have persistent effects, and do not reset upon departing mid-task.[4]

Plot

[edit]Samos Hagai, the Green Sage and master of Green Eco, has long attempted to uncover the mysteries of the Precursors, an ancient civilization responsible for creating monoliths and harnessing Eco, the world's life energy. He believes the answers to these mysteries lie with Jak, a boy unaware of his destiny and initially uninterested in Samos's guidance. Defying Samos's warnings, Jak and his friend Daxter embark on an adventure to Misty Island. There, they overhear two mysterious figures instructing a group of Lurkers — primate-like creatures — to search for Precursor artifacts and Eco while planning an attack on a nearby village. Jak and Daxter discover a pit of Dark Eco, a dangerous substance. Daxter accidentally falls into it after a confrontation with a Lurker, transforming him into an ottsel, a small, furry creature. Jak and Daxter return to Samos, who reveals that only Gol Acheron, a Sage who has studied Dark Eco extensively, might reverse Daxter's transformation. However, Gol resides far to the north, and the journey requires passing through the treacherous Fire Canyon. Keira, Samos's daughter, offers to lend her heat shielded Zoomer, which requires Power Cells to withstand the canyon's heat.

While collecting Power Cells, Jak and Daxter prevent the Lurkers from breaching a Dark Eco silo on Misty Island. This attracts the attention of the two figures, who plot to thwart them, and they unleash a giant Lurker named Klaww in Rock Village. Jak and Daxter gather enough Power Cells to fuel the Zoomer's heat shield, allowing them to cross Fire Canyon and reach Rock Village. There, they find the Blue Sage's lab in disarray and learn that the village is being bombarded by flaming boulders. They collect more Power Cells to activate a levitation machine to remove a massive boulder blocking the path to Klaww, whom they defeat. Continuing their journey through the Mountain Pass and reaching the Volcanic Crater, they discover the Red Sage's lab in chaos, hinting at foul play. Gol and his sister Maia, the two figures from Misty Island, reveal themselves, having been corrupted by Dark Eco. They have kidnapped the other Sages to harness their powers and open Dark Eco silos to reshape the world. They boast of controlling Dark Eco, a feat even the Precursors could not achieve, and plan to use a Precursor Robot to access vast underground Dark Eco reserves.

As Jak and Daxter take the Zoomer to Gol and Maia's citadel, Samos is also captured, prompting the pair to storm the citadel. They free the four Sages, who combine their Eco powers to disable a force shield protecting the Precursor Robot. Jak and Daxter confront Gol and Maia, who are operating the robot to open a Dark Eco silo. During the battle, the Sages' Eco powers merge into Light Eco, a rare and powerful substance. Daxter, despite hoping Light Eco could restore his form, chooses to let Jak use it to destroy the robot. Jak's powerful Light Eco blast obliterates the robot, and Gol and Maia are presumed destroyed when their cockpit falls into the Dark Eco and the silo closes. In the aftermath, Samos praises Jak and Daxter as heroes, though Daxter remains an ottsel, as Gol's help is lost. The group discovers a massive Precursor Door requiring 100 Power Cells to open. If Jak and Daxter have collected all 100, the door opens, revealing a dazzling light, leaving the group in awe of its mysterious significance.

Development

[edit]Conceptualization and initial development

[edit]The project that would become Jak and Daxter began in 1998, during the development of Crash Team Racing (CTR), the final Crash Bandicoot title by Naughty Dog.[13] Disenchanted with their lack of control over the Crash Bandicoot intellectual property, owned by Universal Interactive, and feeling creatively exhausted by the series, co-founders Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin decided to pursue a new project.[13][14] The vision was to create an open world, seamless 3D action-adventure game that combined platforming elements akin to Banjo-Kazooie, the epic storytelling of The Legend of Zelda, and the high-energy action of Crash Bandicoot.[13][15] This ambition was fueled by the anticipated power of the PlayStation 2 (PS2), which promised to overcome the hardware limitations of the PlayStation that had constrained earlier efforts at open world gameplay.[16]

Initial development focused on building a new game engine, with Andy Gavin and a small team of programmers, including Stephen White, starting work in January 1999 under the codename "Project Y"; the title was a progression from CTR's early working title "Project X".[13][15] This period coincided with the completion of CTR, allowing a gradual transition of resources.[13][16] The team aimed to create a single, cohesive world without loading screens, a goal inspired by the limitations of Crash Bandicoot's discrete levels and the success of titles like Spyro the Dragon (1998) and Super Mario 64 (1996).[16][17] The engine development included creating a proprietary programming language called Game Oriented Assembly Lisp (GOAL), designed to streamline development by allowing real-time code modifications, significantly reducing iteration times compared to the Crash series.[17]

By January 2000, with CTR completed, Naughty Dog expanded the Jak and Daxter team to 36 members, more than doubling the size of the CTR team.[15][16] This growth was particularly pronounced in the animation department, which grew to include six full-time animators and four additional support staff, many recruited from outside the gaming industry, including Disney and Nickelodeon. The increased team size reflected the project's scale, with Jak and Daxter requiring over three times the manpower of the largest Crash game.[16] Additional game design and programming was provided by Mark Cerny via his independent consultancy Cerny Games.[18][19]

Art design

[edit]

Early concepts for the game included a third main character, a pet-like creature intended to evolve based on player actions, similar to a Tamagotchi, but this idea was abandoned to focus on two core characters: Jak, a silent, athletic hero, and Daxter, his comedic sidekick.[13][15] Crash Bandicoot character designer Charles Zembillas was a key character designer for Jak and Daxter. He was initially respected at Naughty Dog, given a private workspace to create untainted designs for Jak and Daxter, which required a year-long process and 650 concepts due to the PS2's higher polygon limits, allowing for detailed, sculptural designs.[20] Jak's design went through multiple iterations, initially exploring animal-like features (which co-designer Evan Wells compared to ThunderCats) and chain physics such as ponytails, before settling on a long-eared, elfin appearance.[13][15] Daxter, inspired by Mushu from Mulan (1998), was designed as a loquacious ottsel (otter-weasel hybrid) to provide humor and commentary, complementing Jak's mute protagonist role. The character design drew from a blend of Western and Eastern aesthetic influences, including Joe Madureira's Battle Chasers and Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1997), while the idyllic village setting, character interactions and quest setup were influenced by Asterix.[15][16][21] Animator John Kim based Jak and Daxter's movements on Aladdin and Abu from Disney's Aladdin (1992).[22]

The game's world was designed to be cohesive and immersive, with levels interconnected to allow seamless transitions and visible landmarks across areas, such as the view of multiple locations from the top of the Forbidden Temple.[23] This required meticulous level design to manage memory spooling and hide loading processes, a task complicated by the need to maintain spatial logic (e.g., ensuring caves fit realistically within mountains).[13] The environments drew inspiration from Japanese landscapes, with the development team collecting several photographic reference books to create a fantastic world rooted in reality.[15]

Art director Bob Rafei pointed to Star Wars, Disney, and Studio Ghibli as key touchstones during the story's conceptualization phase.[23] The story was made to be more ambitious than those of Crash Bandicoot, with a mythos connected to the game's world.[14] Over 50 minutes of real-time cutscenes, rendered in-engine, were created to deliver Disney-quality storytelling.[13][15] The animation team produced approximately 30 seconds of finished animation per week, a pace comparable to feature films, despite challenges like late voice recordings.[13] Focus testing influenced level redesigns to reduce frustration, balancing designer freedom with player accessibility.[16]

To Zembillas' frustration, he was credited for "additional character design", which he felt downplayed the extent of his contributions. After the game's launch, he sent an angry email to Naughty Dog staff, warning them to avoid him in person. As a result of this credit, Zembillas was not recognized in the nomination of Daxter for "Original Game Character of the Year" in the Game Developers Choice Awards, nor was he mentioned in Naughty Dog's acceptance speech. Zembillas insisted Daxter was wholly his creation, as he worked in isolation and produced numerous iterations, though he distanced himself from Jak's "Dragon Ball Z haircut", calling it derivative, and noted that Jak II's design tweaks aligned more with his original vision.[20][24]

Technical challenges and innovations

[edit]The development of Jak and Daxter was marked by significant technical challenges, primarily due to the team's ambition to create a seamless, load-free world with high polygon counts and grand vistas.[13] The PS2's complex architecture posed difficulties, especially in the absence of established libraries or examples early in its lifecycle.[25] Naughty Dog secured an early PS2 software development kit in 1999, smuggled into the United States due to export restrictions, allowing the team to begin engine development despite incomplete hardware and firmware.[14][23]

The game engine, comprising approximately nine specialized renderers, was rewritten multiple times to optimize performance, achieving a consistent 60 frames per second with no pop-up or draw-in issues.[15] Key innovations included a proprietary mesh tessellation and reduction scheme, initially developed for CTR and enhanced for Jak and Daxter, which allowed distant objects to use simplified models (e.g., a cube appearing as a sphere up close) to manage polygon counts efficiently.[16][17] The team also developed a sophisticated camera system to navigate the complex 3D world, addressing issues like motion sickness, a problem observed in focus tests for games like Spyro and Banjo-Kazooie.[17][21] The camera combined automated intelligence with optional manual control, using tuned parameters and creature-driven messages to maintain visibility without player intervention.[17]

The use of GOAL, while innovative, presented significant challenges. Its development, led solely by Gavin, created bottlenecks, as only he fully understood its complexities. The language's real-time code execution and cooperative multitasking capabilities were powerful but introduced issues like slow garbage collection, which could halt development for up to 15 minutes.[17] Additionally, the team struggled with artist tools, as existing modeling packages like Maya could not handle the game's massive geometry.[16] Custom plug-ins were developed, but their text-based interfaces were initially cumbersome, requiring later improvements by artists like menus and visualization aids.[13][17]

Audio and localization

[edit]The soundtrack was composed by Josh Mancell and produced by Mark Mothersbaugh, while the voice-acting was recorded in the New York City-based Howard Schwartz Recording facility.[18] The game was recorded in six languages, employing a total of 126 voice actors, including Max Casella as Daxter and Twisted Sister's lead vocalist Dee Snider as Gol.[16] Jak's silence was driven by Rubin's belief that a silent protagonist maintained player immersion, avoiding the risk of alienating players with unwanted character traits, as seen in games like Gex.[23] In hindsight, Evan Wells and programmer Greg Omi questioned the decision to keep Jak silent, with suggestions for dialogue to enhance character dynamics in potential sequels.[13]

Audio presented significant hurdles. The game featured original music, sound effects, ambient sounds, and extensive dialogue, but the loss of the initial sound programmer early in development led to mismanagement. Sound effects were numerous and difficult to balance, while spooled Foley effects suffered from synchronization issues due to late implementation. White felt the music lacked the cohesive direction of previous Crash titles, and localization for multiple languages was complicated by insufficient testing, leading to undetected errors. Despite these issues, the team's localization strategy, using swappable data files and standardized timing units, allowed simultaneous development of NTSC and PAL versions, ensuring consistent physics and animation playback across regions.[17]

Business context and Sony acquisition

[edit]The game's development occurred against a backdrop of significant business changes. Frustrated by their lack of control over Crash Bandicoot and the financial burdens of independent development, Rubin and Gavin sold Naughty Dog to Sony in early 2001 for an undisclosed sum. This acquisition, prompted by discussions with Sony executives like Kelly Flock, secured financial stability and allowed Naughty Dog to focus on creative risks without the pressure of self-funding. The $14 million budget for Jak and Daxter, with Rubin and Gavin personally contributing $2.25 million each, underscored the escalating costs of next-generation development, making Sony's backing critical. Sony's trust in Naughty Dog, built on the studio's track record of delivering four successful Crash titles on schedule, allowed significant creative freedom. The acquisition formalized a long-standing partnership, with Sony providing marketing and technical support while leaving Naughty Dog's culture and operations largely intact.[14] This relationship facilitated the game's global appeal, with input from Sony's worldwide producers shaping its multicultural design.[16]

Marketing and release

[edit]Even before the game's announcement at E3 2001, "Project Y" was highly anticipated.[26] The game's title was revealed on May 14,[27] and the game was revealed at E3 2001 two days later, with a scheduled winter 2001 release.[28] As development neared completion, Naughty Dog faced intense pressure to meet deadlines; the subsequent six months following the E3 showcase were a "blur" of script rewrites, engine overhauls, and level building.[13] The final boss was integrated just 48 hours before submission. A one-month delay past Thanksgiving 2001 allowed critical polishing, ensuring the game met Naughty Dog's quality standards.[14]

In November, a game demo and coupon for the game's retail copy was distributed to Cingular Wireless customers who activated service with an Ericsson phone or purchased an Ericsson accessory.[29] A browser game was developed and released in 2001 to promote the game. After becoming lost media, it was later restored and made playable by archivists and fans of the Jak and Daxter series.[30] The game was originally slated for a North American ship date of December 11, but was moved up to December 4.[31][32]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 90/100[33] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | 4/5[12] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 24.5/30[34] |

| EP Daily | 9.5/10[10] |

| Eurogamer | 9/10[6] |

| Famitsu | 34/40[35] |

| Game Informer | 9.25/10[36] |

| GamePro | 4.5/5[11] |

| GameRevolution | A-[2] |

| GameSpot | 8.8/10[1] |

| GameSpy | 4.5/5[8] |

| GameZone | 9.8/10[7] |

| IGN | 9.4/10[4] |

| Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine | 5/5[9] |

| PALGN | 8/10[3] |

| X-Play | 4/5[5] |

Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy received "universal acclaim", according to review aggregator Metacritic.[33] The game met and exceeded the expectations of IGN's David Dzyrko, which had been built by the media and audience's anticipation of the title. He proclaimed it to be one of the greatest platformers released, standing alongside the best titles by Nintendo and Rare.[4] Brian Gee of GameRevolution deemed the game a benchmark for its genre, claiming that it "will change the way you look at platformers".[2] Mugwum of Eurogamer declared the game to have surpassed Super Mario 64 and Banjo-Kazooie, citing its strong combination of elements despite having no great innovations.[6]

Critics hailed the game as a visual and technical masterpiece for its vibrant, detailed environments, seamless rendering, and absence of load times, setting a benchmark for platformers on the PS2. Dzyrko described the worlds as "breathtaking", citing the environmental details and realistic day-night lighting shifts.[4] Andrew Reiner of Game Informer praised the meticulous environmental details, saying that he often "found [him]self staring in awe" at them.[36] Shane Satterfield of GameSpot called it one of the PS2's most visually impressive titles, emphasizing its vast polygon counts, vivid high-resolution textures with no pixelation, and real-time lighting.[1] Scott Alan Marriott of AllGame lauded the visuals as "near perfect", citing vibrant colors, fluid animation, dramatic lighting, and weather effects.[12] Joe Rybicki of Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine compared the visual style to a "really high-quality hand-drawn cartoon" and admired the subtle environmental details such as the coppery, metallic sheen of the Precursor ruins and the slight heat haze in the volcanic area.[9]

The massive draw distance was highlighted, with Rybicki marveling at seeing every area from a high place, and Louis Bedigian of GameZone hailing the game as "the first 3D platformer to fully render every background as far out as the eye can see".[a] The special effects and character animation were also commended. Marriott detailed the lighting effects and comical animations for the enemies, who react upon spotting Jak or registering a hit against him.[12] Mugwum noted the heat haze effects, real-time lighting and weather cycles.[6] Barak Tutterrow of GameSpy singled out the volcanic area as a personal favorite for its amount of effects without slowdown.[8] Dzyrko praised the character animation and body language as rivaling that of high-budget animated films.[4] Satterfield compared the fluid animation to Disney productions and noted that the facial animations were perfectly synched with the dialogue.[1]

The seamless, interconnected world was regarded as groundbreaking in its presentation as a living, immersive environment. Critics emphasized that the absence of load times contributed to the impression of a cohesive and fully realized world.[b] Dzyrko, Mugwum and Tutterrow highlighted the persistent progression system in which completed tasks and actions remain in effect, contrasting the resetting levels of Super Mario 64.[4][6][8] Gee praised the freedom of exploring such a large environment as a platformer benchmark, estimating that it would take an hour to traverse one end of the game's world to the other.[2] Bedigian described the world as bigger than any other platformer before it, claiming the game would not have been possible on any other console.[7] Satterfield noted that the game's areas were massive, but lacked warp points within them, which sometimes made navigation tedious. He also faulted the use of invisible barriers, which limited exploration.[1]

Although the gameplay was considered polished and enjoyable, critics deemed it lacking in innovation, relying on familiar platforming tropes like collecting items and performing fetch quests. Satterfield noted that the game's objectives "maintain the status quo" for platformers, but he appreciated the puzzles that exploited timed Eco effects, which brought excitement to those particular objectives.[1] Chris Johnston of Electronic Gaming Monthly (EGM) said that the game's polish and craft made the genre's "old stand-bys" (such as riding vehicles or hitting timed switches) fun, though James "Milkman" Mielke of the same publication criticized the repetitive fetch quests, suggesting that the game's structure would appeal more to younger players.[34] Marriott described the game as a straightforward platformer with familiar objectives (collecting Precursor Orbs and Power Cells), but said that the diversity of the tasks kept the game engaging despite the sense of déjà vu from Super Mario 64, Gex or Spyro.[12] Mugwum praised the game's design of unlimited lives and persistent progress as "a reward structure that deserves mimicry",[6] and Jason D'Aprile of Extended Play credited the frequent save spots for reducing frustration,[5] though Satterfield warned that the three-hit health system may quickly wear patience thin.[1] The lack of bosses, totaling three, was considered a drawback, with Shane Bettenhausen of EGM identifying the flaw as a holdover from Super Mario 64.[c]

The controls were regarded as tight and responsive; Dzyrko praised them as having the "Mario feel" of inherently fun movement, and Bedigian derived particular enjoyment from using Jak's rolling jump for navigation.[d] Matt Keller of PALGN additionally called the camera "one of the best ever", highlighting its quick adjustment, though Rybicki and D'Aprile found it somewhat unwieldy.[3][5][9] Satterfield criticized Jak's small moveset, which limited gameplay depth, suggesting that making Daxter playable at some point could have mitigated the issue.[1] Rybicki noted that Jak's lunging punch attack was occasionally problematic to use near cliffs, and that double-jumping could be hit-or-miss with the analog buttons.[9]

The story was deemed simple and unremarkable, serving as a basic framework for the gameplay. Satterfield called the story a shallow affair with few twists, as was the stereotype of platformers, and said that the dialogue was rarely interesting.[1] Rybicki wished for a deeper story, given the potential of the Precursor mythology, but found the characters entertaining, and he and Dzyrko appreciated the story establishing reasons for collecting the game's items, lessening the usual arbitrariness.[4][9] Reactions to Daxter's humor were unfavorable. Reiner found his quips somewhat annoying but occasionally funny.[36] Satterfield noted that his jokes tended to fall flat,[1] and Keller said that he had a habit of whining and causing trouble by saying too much.[3] Mielke dismissed his "Jar Jar-esque zaniness" as juvenile.[34]

Reactions to the audio were generally positive. Critics praised the voice-acting, with Gee pointing out Dee Snider and Max Casella's involvement and Tutterrow specifying Keira, the Geologist and Boggy Billy as stand-out voices.[e] The sound effects were regarded as immersive; Dzyrko and Marriott emphasized the environmental ambience, and they and Tutterrow highlighted the various footstep sounds, with Tutterrow favoring the walks through metal buildings.[4][8][12] The music had a more mixed reception. Some deemed the soundtrack sparse and unmemorable,[1][7][8][34] though Dzyrko, D'Aprile and Reiner were more positive.[4][5][36] Mugwum said that the soundtrack's modesty complemented the pleasureful experience,[6] and Keller highlighted its dynamic changes.[3]

The game's brevity was noted, with estimates generally falling between 10-15 hours.[3][6][8] Tutterow attributed the game's length to a balanced difficulty,[8] while Keller considered the difficulty too low.[3] Rybicki acknowledged the game's short length, but said that the game never felt too easy despite the unlimited lives.[9] D'Aprile regarded the game as a "long and challenging endeavor", assessing the difficulty as middling,[5] and Bettenhausen described it as a "colossal adventure" that cannot be completed within a weekend.[34]

Sales and awards

[edit]After its release in late 2001, the game went on to sell over 1 million copies, promoting it to "Greatest Hits" and reducing the price. By July 2006, it had sold 1.7 million copies and earned $49 million in the United States, and had become the best-selling Jak and Daxter game in that country. Next Generation ranked it as the 19th highest-selling game launched for the PS2, Xbox, or GameCube between January 2000 and July 2006 in the United States. Combined sales of Jak and Daxter games reached 4 million units in the United States by July 2006.[37] As of 2007, Jak and Daxter has sold almost 2 million copies (1.97 million) in the United States alone.[38] Jak and Daxter received a "Gold Prize" at Sony's PlayStation Awards in Japan for sales of over 500,000 units.[39]

In IGN PS2's Game of the Year Awards, Jak and Daxter won the award for Best Platformer and was co-runner-up (with Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance) for Best Graphics, behind Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty.[40][41] The game received two nominations in the 5th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Game Design and Console Action/Adventure Game of the Year,[42] but lost to Grand Theft Auto III and Halo: Combat Evolved respectively.[43] The game was a nominee for GameSpot's annual "Best Platform Game" award among console games, which went to Conker's Bad Fur Day.[44] At the 2002 Game Developers Choice Awards, Daxter won the Original Game Character of the Year award. The game was also nominated for Excellence in Programming and Excellence in Visual Arts, but respectively lost to Black & White and Ico.[45] In the inaugural NAVGTR Awards, the game received three nominations for Outstanding Control Precision, Outstanding Graphics (Technical), and Outstanding Original Action Game, losing the first two to Halo: Combat Evolved and the latter to Max Payne.[46] The game was runner-up for PS2 Platform Game of the Year in GameSpy's 2001 Game of the Year Awards, behind Klonoa 2: Lunatea's Veil.[47]

| Year | Award Ceremony | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | IGN PS2 Game of the Year Awards | Best Platformer[40] | Won |

| Best Graphics[41] | Runner-up | ||

| 5th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards | Outstanding Achievement in Game Design[42] | Nominated | |

| Console Action/Adventure Game of the Year[42] | Nominated | ||

| GameSpot Presents: The Best and Worst of 2001 | Best Platform Game[44] | Nominated | |

| 2nd Annual Game Developers Choice Awards | Original Game Character of the Year (Daxter)[45] | Won | |

| Excellence in Programming (Andy Gavin and Stephen White for programming)[45] | Nominated | ||

| Excellence in Visual Arts (Greg Griffith, Bill Harper, John Kim, Jordan Pitchon, Bob Rafei, Josh Scherr and Rob Titus for animation)[45] | Nominated | ||

| 1st NAVGTR Awards | Outstanding Control Precision[46] | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Graphics, Technical[46] | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Original Action Game[46] | Nominated | ||

| GameSpy Game of the Year Awards | PS2 Platform Game of the Year[47] | Runner-up |

Legacy

[edit]Naughty Dog developed two sequels, Jak II (2003) and Jak 3 (2004), and the racing game Jak X: Combat Racing (2005).[14] In 2012, a remastered port of the game was included in the Jak and Daxter Collection for the PlayStation 3, and for the PlayStation Vita in 2013.[48][49] It was also released as a "PS2 Classic" port for the PlayStation 4 in 2017.[50] In 2022, a group of fans reverse-engineered the game and unofficially ported it to modern PC platforms; titled OpenGOAL.[51]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Satterfield, Shane (December 4, 2001). "PlayStation2 Reviews: Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy Review". GameSpot. CNET Networks. Archived from the original on December 7, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gee, Brian (December 2001). "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy - PlayStation 2 Review". GameRevolution. Archived from the original on January 26, 2002. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Keller, Matt (February 5, 2003). "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy Review". PALGN. Archived from the original on August 13, 2004. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Zdyrko, David (December 4, 2001). "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy review". IGN. Snowball.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h D'Aprile, Jason (January 9, 2002). "Jak and Daxer: the Precursor Legacy (PS2) Review". Extended Play. TechTV. Archived from the original on January 24, 2002. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mugwum (February 17, 2002). "Reviews: Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on May 28, 2003. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bedigian, Louis (December 12, 2001). "PlayStation 2 Game Reviews - Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". GameZone. Archived from the original on February 20, 2002. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tutterrow, Barak (December 10, 2001). "Reviews: Jak & Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". GameSpy. Archived from the original on December 17, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rybicki, Joe (January 2002). "PS2 Reviews: Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. Ziff Davis. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Mowatt, Todd (December 17, 2001). "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy Review". The Electric Playground. Archived from the original on December 29, 2002. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c Four-Eyed Dragon (February 2002). "ProReviews: Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". GamePro. No. 161. International Data Group. p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Marriott, Scott Alan. "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Design & Development: The Art of Making a Game - Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". Game Informer. No. 106. Sunrise Publications. February 2002. pp. 58–61.

- ^ a b c d e f Moriarty, Colin (October 4, 2013). "Rising to Greatness: The History of Naughty Dog". IGN. Archived from the original on June 6, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Katayev, Arnold (December 26, 2001). "Interview with Naughty Dog staff". PSX Extreme. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Halverson, Dave (December 2001). "Dynamic Duo - Jason Rubin interview". Play. No. 1. pp. 16–21. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h White, Stephen (July 10, 2002). "Postmortem: Naughty Dog's Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". Gamasutra. UBM plc. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Naughty Dog (December 3, 2001). Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy (PlayStation 2). Sony Computer Entertainment. Level/area: Credits.

- ^ Ivan, Tom (February 13, 2020). "Who Is Mark Cerny, The Man Behind PS5?". Video Games Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Henley, Stacy (March 6, 2020). "The Artist Who Helped Create Crash, Spyro, and Jak and Daxter Has a Bone to Pick". EGMNOW. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2025.

- ^ a b Guise, Tom (December 10, 2001). "Naughty Dog: The Interview". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009.

- ^ The Making of Jak & Daxter. YouTube. PlayStation Europe. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on January 2, 2025. Retrieved May 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Avard, Alex (March 12, 2021). ""We might have overachieved, to be honest": The making of Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on March 19, 2025. Retrieved May 20, 2025.

- ^ Zembillas, Charles (November 18, 2012). "Jak and Daxter history - The Road to Jak - Part 12". The Art of Charles Zembillas. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ Dutton, Fred (August 24, 2012). "Behind the Classics: Jak & Daxter". PlayStation.Blog. Sony Interactive Entertainment. Archived from the original on February 11, 2025.

- ^ "Sneak Peek at Naughty Dog's Game". IGN. Snowball.com. May 11, 2001. Archived from the original on December 17, 2001. Retrieved May 21, 2025.

- ^ "Naughty Dog's Secret Project Named". IGN. Snowball.com. May 14, 2001. Archived from the original on December 2, 2001. Retrieved May 21, 2025.

- ^ Perry, Douglass C. (May 16, 2001). "E3 2001: Naughty Dog Debuts Jak and Daxter". IGN. Snowball.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2001. Retrieved May 21, 2025.

- ^ Ahmed, Shahed (November 5, 2001). "Jak and Daxter demo from Cingular Wireless". GameSpot. CNET Networks. Archived from the original on June 24, 2004. Retrieved May 21, 2025.

- ^ Henley, Stacey (April 8, 2020). "How archivists and fans saved a long-lost Jak & Daxter Flash game from obscurity". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Jak and Daxter to Ship Early". IGN. Snowball.com. November 17, 2001. Archived from the original on November 18, 2001. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ Ahmed, Shahed (December 4, 2001). "SCEA outlines its PS2 release calendar". GameSpot. CNET Networks. Archived from the original on December 6, 2001. Retrieved June 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy for PlayStation 2 Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bettenhausen, Shane; Johnston, Chris; Mielke, James (January 2002). "Review Crew: Jak and Daxter:: The Precursor Legacy". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 150. Ziff Davis. p. 210.

- ^ プレイステーション2 – ジャック×ダクスター 旧世界の遺産. Weekly Famitsu. No.915 Pt.2. Pg.70. 30 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Reiner, Andrew (January 2002). "Reviews: Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy". Game Informer. No. 105. Sunrise Publications. p. 76.

- ^ Campbell, Colin; Keiser, Joe (July 29, 2006). "The Top 100 Games of the 21st Century". Next Generation. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007.

- ^ "US Platinum Videogame Chart". The MagicBox. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ "Naughty Dog – 30 Year Timeline". Naughty Dog. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "Winner of the Best Platformer of 2001". IGN. January 17, 2002. Archived from the original on February 10, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ a b "PS2 Game of the Year 2001". IGN. January 18, 2002. Archived from the original on June 24, 2002. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences Announces Finalists For The 5th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on June 2, 2002. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Announces Recipients of Fifth Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on August 11, 2002. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ a b "GameSpot's Best and Worst Video Games of 2001: Best Platform Game". GameSpot. February 23, 2002. Archived from the original on April 12, 2002.

- ^ a b c d "2nd Annual Game Developers Choice Awards". Game Developers Choice Awards. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "2001 Winners". National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers. November 21, 2002. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ a b "Game of the Year Awards - 2001: PS2 Platform Game of the Year". GameSpy. Archived from the original on September 14, 2004. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ "Jak and Daxter Collection hits PS3 February 7". Blog.us.playstation.com. January 24, 2012. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Jak & Daxter Trilogy arrives on PSVita". Blog.eu.playstation.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Pardilla, Bryan (April 3, 2017). "Jak and Daxter PS2 Classics Coming to PS4 Later This Year". PlayStation Blog. Sony Interactive Entertainment. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Baxter, Daryl (December 28, 2022). "Decompilations could be the solution to ports and remakes in the future". TechRadar. Retrieved January 6, 2023.