High-speed rail in China

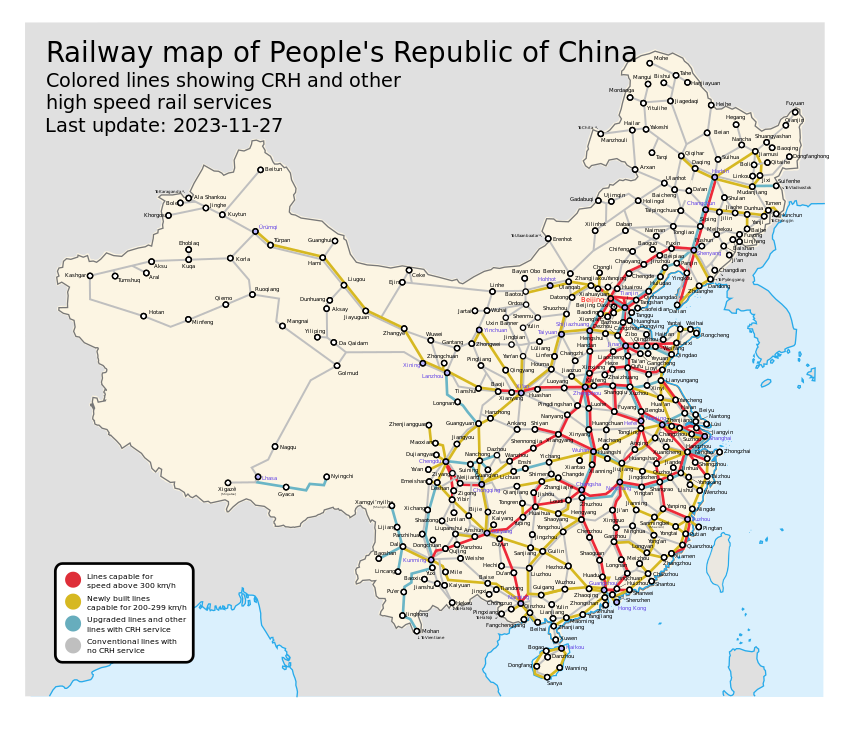

The high-speed rail (HSR, Chinese: 高铁; pinyin: Gāotiě) network in the People's Republic of China (PRC) is the world's longest and most extensively used.[1][2][3] The HSR network encompasses newly built rail lines with a design speed of 200–380 km/h (120–240 mph).[4] China's HSR accounts for two-thirds of the world's total high-speed railway networks.[5][6] Almost all HSR trains, tracks, and services are owned and operated by the China State Railway Group Co. under the brand China Railway High-speed (CRH).

Since the mid-2000s, China's high-speed rail network has experienced rapid growth. CRH was introduced in April 2007, with the Beijing-Tianjin intercity rail, which became fully operational in August 2008, being the first passenger-dedicated HSR line. Currently, the HSR extends to all provincial-level administrative divisions and the Hong Kong SAR with the exception of Macau SAR.[note 1][note 2][note 3]

Notable HSR lines in China include the Beijing–Kunming high-speed railway, currently the world's longest HSR line in operation, at a length of 2,760 km (1,710 mi), and the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway, which is recognized as the world's fastest operating conventional train services. Additionally, the Shanghai Maglev is the world's first high-speed commercial magnetic levitation (maglev) line that reaches a top speed of 431 km/h (268 mph).[8]

Technology

[edit]Definition and terminology

[edit]In China, high-speed rail refers to rail services operating at speeds exceeding 200 km/h (124 mph). The system generally consists of passenger-dedicated lines (PDLs) with a design speed of 350 kilometres per hour (217 mph), which form the backbone of the national network; regional lines with a design speed of 250 kilometres per hour (155 mph), providing fast interprovincial connections; and intercity lines with a design speed of 200 to 350 kilometres per hour (124 to 217 mph), serving metropolitan areas with more frequent stops for regional service.[9]

Electric multiple unit (EMU) trainsets typically consist of 8 or 16 cars and are designed for frequent service with relatively light axle loads. EMU services running below 200 km/h (124 mph) or on mixed-traffic lines are not classified as high-speed rail unless the line is specifically intended for future speed upgrades.

In practice, high-speed rail services in China are divided into three categories:

- G-series trains are the fastest and most common, operating at speeds up to about 350 km/h (217 mph) on dedicated high-speed lines. Example: the G7 service between Beijing South and Shanghai Hongqiao, running at 350 km/h.

- D-series trains usually run at 200–250 km/h (124–155 mph). They were once common on major daytime routes but have largely been replaced by G-trains. Some are overnight sleeper services, such as the three daily D-trains between Beijing and Shanghai.

- C-series trains serve short intercity routes, typically 200–350 km/h (124–217 mph). Example: services on the Beijing–Tianjin Intercity Railway reach 350 km/h and complete the trip in approximately 30 minutes.

Technology transfer

[edit]Acquiring high-speed rail technology had been a major goal of Chinese state planners. Chinese train-makers, after receiving transferred foreign technology, have been able to achieve a degree of self-sufficiency in making the next generation of high-speed trains by producing key parts and improving upon foreign designs.

Examples of technology transfer include Mitsubishi Electric’s MT205 traction motor and ATM9 transformer to CSR Zhuzhou Electric, Hitachi’s YJ92A traction motor and Alstom's YJ87A Traction motor to CNR Yongji Electric, Siemens’ TSG series pantograph to Zhuzhou Gofront Electric.

For foreign train manufacturers, technology transfer was a crucial part of gaining market access in China. Bombardier, the first foreign train manufacturer to form a joint venture in China, has been sharing technology for the manufacture of railway passenger cars and rolling stock since 1998. Zhang Jianwei, President of Bombardier China, stated that in a 2009 interview, “Whatever technology Bombardier has, whatever the Chinese market needs, there is no need to ask. Bombardier transfers advanced and mature technology to China, which we do not treat as an experimental market.”[10] Unlike other series, which have imported prototypes, all CRH1 trains have been assembled at Bombardier's joint venture with CSR, Bombardier Sifang in Qingdao.

Kawasaki's cooperation with CSR did not last as long. Within two years of cooperation with Kawasaki to produce 60 CRH2A sets, CSR began in 2008 to build CRH2B, CRH2C, and CRH2E models at its Sifang plant independently without assistance from Kawasaki.[11] According to CSR president Zhang Chenghong, CSR "made the bold move of forming a systemic development platform for high-speed locomotives and further upgrading its design and manufacturing technology. Later, we began to independently develop high-speed CRH trains with a maximum velocity of 300–350 kilometers per hour, which eventually rolled off the production line in December 2007."[12] Since then, CSR has ended its cooperation with Kawasaki.[13] Kawasaki challenged China's high-speed rail project for patent theft, but backed off the effort.[14]

Rolling stock

[edit]

China Railway High-speed runs different electric multiple unit trainsets, the name Hexie Hao (simplified Chinese: 和谐号; traditional Chinese: 和諧號; pinyin: Héxié Hào; lit. 'Harmony') is for designs which are imported from other nations and designated CRH-1 through CRH-5 and CRH380A(L), CRH380B(L), and CRH380C(L). CRH trainsets are intended to provide fast and convenient travel between cities. Some of the Hexie Hao train sets are manufactured locally through technology transfer, a key requirement for China. The signalling, track and support structures, control software, and station design are developed domestically with foreign elements as well. By 2010, the truck system as a whole is predominantly Chinese.[15] China currently holds several new patents related to the internal components of these trains, redesigned in China to allow the trains to run at higher speeds than the foreign designs allowed. However, these patents are only valid within China, and as such hold no international power. The weakness on intellectual property of Hexie Hao causes obstruction for China to export its high-speed rail related product, which leads to the development of the completely redesigned train franchise called Fuxing Hao (simplified Chinese: 复兴号; traditional Chinese: 復興號; pinyin: Fùxīng Hào; lit. 'Rejuvenation') that is based on indigenous technologies.[15][16][17][18]

Maglev

[edit]The world's first commercial maglev line, capable of speeds up to 430 km/h, opened in Shanghai in 2002 using German technology, linking Longyang Road station with Shanghai Pudong International Airport. On October 19, 2010, the Ministry of Railways announced the beginning of research and development of "super-speed" railway technology, aiming to increase maximum train speeds to over 500 km/h (311 mph).[19]

In October 2016, CRRC announced research and development of a 600 km/h (373 mph) maglev train, the CRRC 600, and the construction of a 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) test track.[20] In June 2020, a prototype trial run was conducted at Tongji University, with a planned launch targeted for 2025.[21]

In July 2021, China's first high-speed maglev train with a designed top speed of 600 km/h rolled off the production line in Qingdao, Shandong. Developed by CRRC Qingdao Sifang, the train underwent testing on dedicated maglev tracks to prepare for commercial operation.[22]

On 17 July 2025, CRRC officially unveiled the 600 km/h high-speed maglev train at the 12th UIC World Congress on High-Speed Rail in Beijing. The train is designed to bridge the gap between conventional high-speed rail (with a maximum operating speed of 350 km/h) and air travel (900–1,000 km/h).[22] Using electromagnetic suspension, the maglev operates without wheel–rail contact, allowing for quieter, smoother, and more efficient service. According to CRRC, the train offers advantages including high speed, safety, reliability, large passenger capacity, lower maintenance costs, and environmental sustainability.[22] The train is expected to enter commercial service within five to ten years and could significantly reduce travel times; for example, the Beijing–Shanghai journey could be shortened from around five hours to about two and a half hours.[22]

Track technology

[edit]

China's high-speed rail network relies heavily on advanced track technology to allow trains to operate safely at high speeds. A key innovation is the widespread use of ballastless tracks, which replace the traditional gravel base with a solid concrete slab. These tracks provide a smoother ride, reduce long-term maintenance costs, and can handle frequent, heavy train traffic.

Over the years, China has developed several types of ballastless track within the Chinese Railway Track System (CRTS), including prefabricated slabs that simplify construction and allow precise standardization. Track designs are optimized for different speeds, train loads, and environmental conditions such as temperature variations and uneven subgrade settlement. Advanced design methods, such as the limit state method, are increasingly used to improve safety and material efficiency compared with older allowable stress method approaches.[23]

Currently, four main types of ballastless track are used in China's high-speed rail network: CRTS I, CRTS II, CRTS III slab, and CRTS double-block. CRTS I, CRTS II slab, and CRTS double-block track types were developed by Chinese railway companies based on technology transferred from Germany and Japan. CRTS III slab track is a Chinese innovation, improving upon previous designs and adapted for domestic conditions.[24]

Technology export

[edit]China has increasingly promoted the export of its high-speed rail technology, with the most significant achievement to date in Indonesia. In October 2023, the Whoosh line between Jakarta and Bandung opened as the first operational high-speed railway in Southeast Asia.[25][26] Built by China Railway Construction Corporation and operated by a joint venture with Indonesian partners, the project is considered the first complete export of China's HSR system, including design, construction, rolling stock, and operations.[27]

China has also participated in projects elsewhere. In Turkey, the China Railway Construction Corporation built a 30 km section of the Ankara–Istanbul high-speed railway completed in 2014.[28] In Europe, Chinese companies are involved in construction of the Belgrade–Budapest railway linking Serbia and Hungary. Moreover, in Southeast Asia, further high-speed rail projects with Chinese involvement are advancing in Thailand and under discussion in Vietnam. Although not designed for the same speeds, China has also exported 160 km/h electrified lines, such as the Boten–Vientiane railway in Laos, often described as part of a broader pan-Asian high-speed corridor.

Beyond completed and under-construction projects, China has signed agreements or placed bids for HSR lines in Russia (the Moscow–Kazan route), Venezuela, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Brazil (São Paulo–Rio de Janeiro), and the United States.[29] While many of these projects remain at the proposal or bidding stage, they reflect China's emergence as a competitor to established Japanese and European suppliers in the global high-speed rail market.

History

[edit]

Precursor

[edit]The earliest example of a fast commercial train service in China was the Asia Express, a luxury passenger train that operated in Japanese-controlled Manchuria from 1934 to 1943.[30] The steam-powered train, which ran on the South Manchuria Railway from Dalian to Xinjing (Changchun), had a top commercial speed of 110 km/h (68 mph) and a test speed of 130 km/h (81 mph).[30] It was faster than the fastest trains in Japan at the time. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, this train model was renamed the SL-7 and was used by the Chinese Minister of Railways.

Early planning

[edit]

State planning for China's current high-speed railway network began in the early 1990s under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. He set up what became known as the "high-speed rail dream" after his visit to Japan in 1978, where he was deeply impressed by the Shinkansen, the world's first high speed rail system.[31] In December 1990, the Ministry of Railways (MOR) submitted to the National People's Congress a proposal to build a high-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai.[32] At the time, the Beijing–Shanghai Railway was already at capacity, and the proposal was jointly studied by the Science & Technology Commission, State Planning Commission, State Economic & Trade Commission, and the MOR.[32] In December 1994, the State Council commissioned a feasibility study for the line.[32]

Policy planners debated the necessity and economic viability of high-speed rail service. Supporters argued that high-speed rail would boost future economic growth. Opponents noted that high-speed rail in other countries was expensive and mostly unprofitable. Overcrowding on existing rail lines, they said, could be solved by expanding capacity through higher speed and frequency of service.[citation needed] In 1995, Premier Li Peng announced that preparatory work on the Beijing Shanghai HSR would begin in the 9th Five Year Plan (1996–2000), but construction was not scheduled until the first decade of the 21st century.

The "Speed Up" campaigns

[edit]In 1993, commercial train service in China averaged only 48 km/h (30 mph) and was steadily losing market share to airline and highway travel on the country's expanding network of expressways.[33][34] The MOR focused modernization efforts on increasing the service speed and capacity on existing lines through double-tracking, electrification, improving grade (through tunnels and bridges), reducing turn curvature and installing continuous welded rail. Through five rounds of "Speed-Up" campaigns in April 1997, October 1998, October 2000, November 2001, and April 2004, passenger service on 7,700 km (4,800 mi) of existing tracks was upgraded to reach sub-high speeds of 160 km/h (100 mph).[35]

A notable example is the Guangzhou–Shenzhen railway, which in December 1994 became the first line in China to offer sub-high-speed service of 160 km/h (99 mph) using domestically produced DF-class diesel locomotives. The line was electrified in 1998, and Swedish-made X 2000 trains increased the service speed to 200 km/h (124 mph). After the completion of a third track in 2000 and a fourth in 2007, the line became the first in China to run high-speed passenger and freight services on separate tracks.

The completion of the sixth round of the "Speed-Up" Campaign in April 2007 brought HSR service to more existing lines: 423 km (263 mi) capable of 250 km/h (155 mph) train service and 3,002 km (1,865 mi) capable of 200 km/h (124 mph).[36][note 4] In all, travel speed increased on 22,000 km (14,000 mi), or one-fifth, of the national rail network, and the average speed of passenger trains improved to 70 km/h (43 mph). The introduction of more non-stop services between large cities also helped to reduce travel time. The non-stop express train from Beijing to Fuzhou shortened travel time from 33.5 hours to less than 20 hours.[39]

In addition to track and scheduling improvements, the MOR also deployed faster CRH series trains. During the Sixth Railway Speed Up Campaign, 52 CRH trainsets (CRH1, CRH2 and CRH5) entered into operation. The new trains reduced travel time between Beijing and Shanghai by two hours to just under 10 hours. Some 295 stations have been built or renovated to allow high-speed trains.[40][41]

The conventional rail v. maglev debate

[edit]The development of the HSR network in China was initially delayed by a debate over the type of track technology to be used. In June 1998, at a State Council meeting with the Chinese Academies of Sciences and Engineering, Premier Zhu Rongji asked whether the high-speed railway between Beijing and Shanghai still being planned could use maglev technology.[42] At the time, planners were divided between using high-speed trains with wheels that run on conventional standard gauge tracks or magnetic levitation trains that run on special maglev tracks for a new national high-speed rail network.

Maglev received a big boost in 2000 when the Shanghai Municipal Government agreed to purchase a turnkey TransRapid train system from Germany for the 30.5 km (19.0 mi) rail link connecting Shanghai Pudong International Airport and the city. In 2004, the Shanghai Maglev Train became the world's first commercially operated high-speed maglev and remains the fastest commercial train in the world with peak speeds of 431 km/h (268 mph) and makes the 30.5 km (19.0 mi) trip in less than 7.5 minutes. Despite an unmatched advantage in speed, the maglev has not gained widespread use in China's high-speed rail network due to high costs, German refusals to share technology and concerns about safety. The price tag of the Shanghai Maglev was believed to be $1.3 billion and was partially financed by the German government. The refusal of the Transrapid Consortium to share technology and source production in China made large-scale maglev production much more costly than high-speed train technology for conventional lines. Finally, residents living along the proposed maglev route raised health concerns about noise and electromagnetic radiation emitted by the trains, despite an environmental assessment by the Shanghai Academy of Environmental Sciences saying the line was safe.[43] These concerns have prevented the construction of the proposed extension of the maglev to Hangzhou. Even the more modest plan to extend the maglev to Shanghai's other airport, Hongqiao couldn't be completed. Instead, a conventional subway line was built to connect the two airports, and a conventional high-speed rail line was built between Shanghai and Hangzhou.[note 5]

While maglev was drawing attention to Shanghai, conventional track HSR technology was being tested on the newly completed Qinhuangdao-Shenyang Passenger Railway. This 405 km (252 mi) standard gauge, dual-track, electrified line was built between 1999 and 2003. In June 2002, a domestically made DJF2 train set a record of 292.8 km/h (181.9 mph) on the track. The China Star (DJJ2) train followed the same September with a new record of 321 km/h (199 mph). The line supports commercial train service at speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph) and has become a segment of the rail corridor between Beijing and Northeast China. The Qinhuangdao-Shenyang Line showed the greater compatibility of HSR on conventional track with the rest of China's standard gauge rail network.

In 2004, the State Council in its Mid-to-Long Term Railway Development Plan, adopted conventional track HSR technology over maglev for the Beijing–Shanghai High Speed Railway and three other north–south high-speed rail lines. This decision ended the debate and cleared the way for rapid construction of standard gauge, passenger dedicated HSR lines in China.[44][45]

Acquisition of foreign technology

[edit]Despite setting speed records on test tracks, the DJJ2, DJF2 and other domestically produced high-speed trains were insufficiently reliable for commercial operation.[46] The State Council turned to advanced technology abroad but made it clear in directives that China's HSR expansion could not solely benefit foreign economies and should also be used to develop its own high-speed train building capacity through technology transfers.[46] This would later allow the Chinese government through CRRC to make the more reliable Fuxing Hao and Hexie Hao trains. The CRH380 series (or family) of trains was initially built with direct cooperation (or help) from foreign trainmakers, but newer trainsets are based on transferred technology, just like the Hexie and Fuxing Hao.

In 2003, the MOR was believed to favor Japan's Shinkansen technology, especially the 700 series.[46] The Japanese government touted the 40-year track record of the Shinkansen and offered favorable financing. A Japanese report envisioned a winner-take all scenario in which the winning technology provider would supply China's trains for over 8,000 km (5,000 mi) of high-speed rail.[47] However, Chinese citizens angry with Japan's denial of World War II war crimes organized a web campaign to oppose the awarding of HSR contracts to Japanese companies. The protests gathered over a million signatures and politicized the issue.[48] The MOR delayed the decision, broadened the bidding and adopted a diversified approach to adopting foreign high-speed train technology.

In June 2004, the MOR solicited bids to make 200 high-speed train sets that can run 200 km/h (124 mph).[46] Alstom of France, Siemens of Germany, Bombardier Transportation based in Germany and a Japanese consortium led by Kawasaki all submitted bids. With the exception of Siemens, which refused to lower its demand of CN¥350 million per train set and €390 million for the technology transfer, the other three were all awarded portions of the contract.[46] All had to adapt their HSR train-sets to China's own common standard and assemble units through local joint ventures (JV) or cooperate with Chinese manufacturers. Bombardier, through its joint venture with CSR's Sifang Locomotive and Rolling Stock Co (CSR Sifang), Bombardier Sifang (Qingdao) Transportation Ltd (BST), won an order for 40 eight-car train sets based on Bombardier's Regina design.[49] These trains, designated CRH1A, were delivered in 2006. Kawasaki won an order for 60 train sets based on its E2 Series Shinkansen for ¥9.3 billion.[50] Of the 60 train sets, three were directly delivered from Nagoya, Japan, six were kits assembled at CSR Sifang Locomotive & Rolling Stock, and the remaining 51 were made in China using transferred technology with domestic and imported parts.[51] They are known as CRH2A. Alstom also won an order for 60 train sets based on the New Pendolino developed by Alstom-Ferroviaria in Italy. The order had a similar delivery structure with three shipped directly from Savigliano along with six kits assembled by CNR's CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles, and the rest locally made with transferred technology and some imported parts.[52] Trains with Alstom technology carry the CRH5 designation.

The following year, Siemens reshuffled its bidding team, lowered prices, joined the bidding for 350 km/h (217 mph) trains and won a 60-train set order.[46] It supplied the technology for the CRH3C, based on the ICE3 (class 403) design, to CNR's Tangshan Railway Vehicle Co. Ltd. The transferred technology includes assembly, body, bogie, traction current transforming, traction transformers, traction motors, traction control, brake systems, and train control networks.

Early passenger-dedicated high-speed rail lines

[edit]Between June and September 2005, the MOR launched bidding for high-speed trains capable of 350 km/h (217 mph), as most of the planned mainlines were designed for speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph) or higher. Alongside the CRH3C, produced by Siemens and CNR Tangshan, CSR Sifang bid to supply 60 sets of CRH2C.

At that time, China's only passenger-dedicated high-speed railway (PDL) was the Qinhuangdao–Shenyang line, which began operating in 2003 at speeds of up to 250 km/h (155 mph) along the Liaoxi Corridor in the Northeast. This situation changed quickly as China embarked on a high-speed rail construction boom.

In 2007, the journey from Beijing to Shanghai still took about 10 hours, with upgraded tracks on the Beijing–Shanghai Railway allowing maximum speeds of only 200 km/h (124 mph). To expand capacity, the MOR ordered 70 16-car trainsets from CSR Sifang and Bombardier Sifang Transportation (BST).

A major turning point came with the launch of the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway, the first line in the world designed for 380 km/h (236 mph), which began construction on April 18, 2008. That same year, the Ministry of Science and the MOR introduced a joint action plan to foster indigenous innovation in high-speed trains. The MOR subsequently initiated three new train projects: the CRH1-350 (Bombardier and BST, later designated CRH380D), CRH2-350 (CSR, later CRH380A/AL), and CRH3-350 (CNR and Siemens, later CRH380B/BL and CRH380CL). These represented a new generation of CRH trains with a top operating speed of 380 km/h (236 mph). In total, 400 of these trains were ordered. On October 26, 2010, the first high-speed train developed indigenously within the CRH series, the CRH380A/AL, entered service on the Shanghai–Hangzhou High-Speed Railway.[53]

After committing to conventional-track high-speed rail in 2006, the government launched an ambitious campaign to build a nationwide network of passenger-dedicated lines. Rail construction spending grew rapidly, from $14 billion in 2004 to $22.7 billion in 2006 and $26.2 billion in 2007.[54] In response to the global financial crisis, this expansion was further accelerated as part of an economic stimulus program. Investments in new rail lines, including high-speed rail, reached $49.4 billion in 2008 and $88 billion in 2009.[54] At the time the government planned to invest $300 billion to construct a 25,000 km (16,000 mi) HSR network by 2020, an early that plan that would later be dramatically exceeded.[55][56]

Expansion, challenges, and recovery

[edit]China's ambitious high-speed rail development began with the 2004 "Mid-to-Long Term Railway Network Plan," establishing a national grid of eight corridors (four north–south, four east–west) totaling 12,000 km (7,456 mi).[57] The Hefei–Nanjing PDL opened April 19, 2008, followed by the Beijing–Tianjin intercity railway on August 1, 2008, featuring the first commercial 350 km/h (217 mph) service.[39] Major milestones included the Wuhan–Guangzhou line (December 2009), which set a world record with average speeds of 312.5 km/h (194.2 mph), and the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway (June 2011), designed for 380 km/h (236 mph) operation.[58][59] By January 2011, China operated the world's longest high-speed network at 8,358 km (5,193 mi).[60]

In 2011, the program experienced a series of setbacks. Among others, railway Minister Liu Zhijun was removed from his position for accepting ¥1 billion in bribes, while official Zhang Shuguang allegedly misappropriated $2.8 billion.[61][62][63] New Minister Sheng Guangzu reduced maximum speeds to 300 km/h (186 mph) amid safety and cost concerns.[64][65][66]

The July 23, 2011 Wenzhou train collision proved catastrophic, killing 40 and injuring 192 when signal failures caused a rear-end collision.[67][68][69] The government suspended new approvals, conducted safety reviews, and further reduced speeds across the network.[70][71] Ridership plummeted from July to September 2011, dropping 151 million trips.[72]

Financial pressures intensified as the MOR's debt reached ¥2.09 trillion (5% of GDP) by mid-2011.[73] Bank lending restrictions halted construction on 10,000 km (6,200 mi) of track, affecting major lines including Xiamen–Shenzhen and Shanghai–Kunming.[74] The government responded with tax cuts on financing bonds and ordered renewed bank lending, raising RMB 250 billion by late 2011.[75]

Recovery began in 2012 as the government renewed investments to stimulate the economy, increasing the MOR budget from $64.3 billion to $96.5 billion.[78] Five new lines totaling 2,563 km (1,593 mi) opened by year-end, extending the network to 9,300 km (5,800 mi).[79] By 2014, 1,580 high-speed trains carried 1.33 million daily passengers (25.7% of total rail traffic), with major lines like Beijing–Shanghai and Shanghai–Nanjing achieving profitability.[80][81] On December 28, 2013, China's high-speed rail network surpassed 10,000 km (6,200 mi) with the opening of several new lines.[82]

Second boom

[edit]In 2014, high-speed rail expansion gained speed with the opening of the Taiyuan–Xi'an, Hangzhou–Changsha, Lanzhou-Ürümqi, Guiyang-Guangzhou, Nanning-Guangzhou trunk lines and intercity lines around Wuhan, Chengdu,[83] Qingdao[84] and Zhengzhou.[84] High-speed passenger rail service expanded to 28 provinces and regions.[85] The number of high-speed train sets in operation grew from 1,277 pairs in June to 1,556.5 pairs in December.[85][86]

In response to a slowing economy, central planners approved a slew of new lines including Shangqiu–Hefei–Hangzhou,[87] Zhengzhou–Wanzhou,[88] Lianyungang–Zhenjiang,[89] Linyi–Qufu,[90] Harbin–Mudanjiang,[91] Yinchuan–Xi'an,[87] Datong–Zhangjiakou,[87] and intercity lines in Zhejiang[92] and Jiangxi.[87]

The government actively promoted the export of high-speed rail technology to countries including Mexico, Thailand, the United Kingdom, India, Russia and Turkey. To better compete with foreign trainmakers, the central authorities arranged for the merger of the country's two main high-speed train-makers, CSR and CNR, into CRRC.[93]

By 2015, six high speed rail lines, Beijing–Tianjin, Shanghai–Nanjing, Beijing–Shanghai, Shanghai–Hangzhou, Nanjing–Hangzhou and Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong were reporting operational profitability.[94] The Beijing–Shanghai was particularly profitable, reporting a 6.6 billion yuan net profit.[95]

In 2016, with the near completion of the National 4+4 grid, a new "Mid-to-Long Term Railway Network" Plan was drafted. The plan envisions a larger 8+8 high speed rail grid serving the nation and expanded intercity lines for regional and commuter services for large metropolitan areas of China.[96] The proposed completion date for the network is 2030.[97]

Since 2017, with the introduction of the Fuxing series of trains, a number of lines have resumed 350 km/h operations, such as Beijing–Shanghai HSR, Beijing–Tianjin ICR, and Chengdu–Chongqing ICR.[98]

The HSR network reached 37,900 km (23,500 mi) in total length by the end of 2020.[99] In 2025, the HSR network will reach a total length of 50,000 km and is expected to grow further.[100]

Development and social impact

[edit]

China's high-speed rail program is designed to provide a fast, reliable, and comfortable mode of transport across one of the world's most densely populated countries.[101][102] Key policy objectives include:

- Economic growth and competitiveness – By increasing passenger rail capacity and freeing conventional lines for freight, HSR enhances productivity and integrates labor markets.[56][103] Freight services benefit from higher payload capacity at lower speeds, which are more profitable than passenger operations.[101]

- Stimulus – Construction projects have generated large-scale employment and boosted demand in steel, cement, and other sectors. Work on the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway alone mobilized about 110,000 workers.[54][103][104]

- Regional integration – HSR links major cities with secondary urban centers, expanding market potential and contributing to higher real estate values in connected areas.[105][106]

- Energy efficiency and sustainability – Electric locomotives consume less energy per passenger-kilometre than cars or aircraft and can use electricity from diverse sources, including renewables, reducing reliance on imported oil.[101]

- Domestic industry development – The HSR program has fostered a globally competitive rail manufacturing sector. Chinese companies have rapidly absorbed and localized foreign technology, and now export high-speed rail equipment.[54] Six years after licensing the Shinkansen E2 design from Kawasaki, CRRC Sifang was able to produce the CRH2A without Japanese input.[107]

Financial sustainability and expansion concerns

[edit]

As China's HSR network approaches 50,000 kilometers, mounting financial concerns have prompted policy reassessment. As of 2022, the China State Railway Group carries debt of approximately US$900 billion, with the system operating at a daily loss of US$24 million as of November 2021.[108]

Regional profitability varies significantly. While several high-speed railways in eastern China have achieved operational profitability since 2015, including the profitable Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed railway which generated CNY 29.6 billion in revenue and CNY 12.7 billion in net profit in 2017, most lines in central and western China operate at losses. The Zhengzhou–Xi'an high-speed railway, Guiyang–Guangzhou high-speed railway, and Lanzhou–Xinjiang high-speed railway face particular challenges due to low ridership, harsh climate conditions, and high maintenance costs.[109]

Critics argue that overbuilding has created financial strain, with some lines and stations seeing minimal service or remaining unopened despite completed construction.[110][111] As China prepares its 2026-2030 five-year plan, analysts have questioned whether certain newly built lines meet central government construction standards, particularly given the country's greater need for freight capacity rather than passenger-only services.[112]

In response to these concerns, the government introduced stricter approval criteria in 2021, requiring new lines duplicating existing routes to demonstrate 80% capacity utilization on existing lines, and mandating that new high-speed lines serve cities with at least 15 million annual trips.[113]

Construction costs and financing

[edit]China achieved relatively low construction costs through standardization of designs and procedures, with average costs of $17–21 million per kilometer according to a 2019 World Bank report—about one-third lower than other countries. Standardized train tracks, rolling stock, and signal systems, combined with bulk purchasing by state-owned corporations, helped keep costs down.[9]

Construction financing is highly capital intensive, with 40-50% provided by the national government through state-owned banks, 40% through Ministry of Railway bonds, and 10-20% by provincial and local governments.[114] The China Rail Investment Corp issued approximately ¥1 trillion (US$150 billion) in debt from 2006 to 2010 to finance HSR construction.[115]

Despite construction efficiency, most lines operate at losses initially. The Beijing-Tianjin intercity railway, for example, required several years to break even despite carrying over 41 million rides in its first two years, due to construction costs of ¥20.42 billion and annual operating costs of ¥1.8 billion including interest payments.[116] The line achieved profitability by 2015. However, many other lines continue to operate at losses, with deficits typically covered by subsidies from local governments.

Overall ridership continues growing as the network expands, and high-speed rail has become more affordable relative to wages. However, in 2016, high-speed rail revenue of ¥140.9 billion still fell short of interest payments of ¥156.8 billion on construction debt.[117] Experts have raised concerns about operational efficiency, noting that China's rail staff productivity index of less than 0.05 is the lowest among countries with significant railway construction, despite the network being one of the world's most intensively used for both freight and passenger service.[118]

Fare cost and airlines

[edit]

A 2019 study by the World Bank Group found that HSR fares in China are low compared to other countries and have attracted passengers from all income levels. It noted that HSR is "very competitive" with bus and aircraft transport for distances between 150 km and 800 km (about 3 to 4 hours travel time). Due to both frequency and high speeds, services operating at 350 km/h (217 mph) remain competitive with air travel for journeys of up to 1,200 km.[9]

The expansion of high-speed rail has significantly reshaped China's domestic aviation market. Research by Cirium Ascend Consultancy in 2025 found that HSR has captured a dominant share of trips under 800 km (500 mi), where it is often faster and more convenient when total travel time from home to boarding is considered. On average, passengers in major Chinese cities save 35–45 minutes reaching and clearing security at HSR stations compared with airports, due to stations’ central locations, shorter access times, and quicker screening processes.[119] This competitive advantage has led to a structural decline in short-haul flights. According to Cirium data, flights of 800 km (500 mi) or less fell from 26.4% of all domestic flights in 2011 to 15.9% in early 2025. Overall flight volumes more than doubled in the same period with airlines shifting capacity to longer domestic routes, international services, and regions not yet served by high-speed rail, such as parts of western China.[119]

Track network

[edit]

China's high-speed railway network is by far the longest in the world. The HSR network reached 48,000 km (30,000 mi) in total length by the end of 2024, with plans to expand to 60,000 km (37,000 mi) by 2030.[120]

Development planning and evolution

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: 2024[121] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The development of China's HSR network has been guided by the Medium- and Long-Term Railway Plan (MLTRP), first approved in 2004 with several major revisions.

The ambition of the program has constantly expanded over time through successive revisions:

- 2004 original plan: Targeted an HSR network of 12,000 km (7,500 mi) by 2020

- 2008 revision: Increased the target to 16,000 km (9,900 mi) by 2020 and removed speed restrictions to allow higher-speed lines

- 2016 revision: Dramatically increased targets to 30,000 km (19,000 mi) by 2020, 38,000 km (24,000 mi) by 2025, and 45,000 km (28,000 mi) by 2030

- 2021 strategy: The "Outline of the Railway-First Strategy for Building a Strong Transportation Nation in the New Era" set an ambitious target of 70,000 km (43,000 mi) by 2035

The 2016 targets have been significantly exceeded, with the network reaching the original 2030 goal by several years. However, current official planning has de-emphasized the 2035 targets in favor of more immediate goals, with the focus shifting to achieving 60,000 km (37,000 mi) by 2030. As China prepares its next five-year plan covering 2026-2030, policymakers face decisions about whether to continue the rapid expansion pace amid growing financial sustainability concerns.[112]

National High-Speed Rail Grid

[edit]HSR lines are generally classified into the following types, covering both the main national grid and additional regional and connecting lines:

- Passenger-dedicated lines (PDLs) with a design speed of 350 km/h (217 mph), forming the backbone of the national network.

- Regional lines connecting major cities with a design speed of 250 km/h (155 mph), providing fast connections across provinces.

- Intercity lines with a design speed of 200–350 km/h (120–220 mph), serving metropolitan areas and offering more frequent stops for regional service.

- Older lines constructed during the early phase of the HSR build out that carry high-speed passenger and express freight services with a design speed of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph).[4]

There are also mixed-use connecting lines and upgraded conventional rail segments that allow high-speed trains to extend beyond dedicated HSR lines, operating at speeds of around 200 km/h (124 mph).

High-speed trains on dedicated HSR corridors can generally reach 300–350 km/h (190–220 mph). On mixed-use or regional lines, passenger services typically operate at peak speeds of 200–250 km/h (120–160 mph). Recent technological developments include maglev trains achieving test speeds over 600 km/h and new-generation bullet trains capable of 400 km/h, potentially reducing Beijing–Shanghai travel time from four hours to three.[112]

The centerpiece of China's HSR expansion is the national high-speed rail grid, which overlays mainly passenger-dedicated lines onto the existing railway network.

Evolution from 4+4 to 8+8 Grid

[edit]The original national HSR grid, known as the "4+4 grid," consisted of eight high-speed corridors—four north–south and four east–west—with a total length of 12,000 km (7,456 mi).[57] Most lines followed existing trunk routes and were designated for passenger traffic only, though some sections carried mixed passenger and freight services. This 4+4 grid was largely completed by 2015.

In July 2016, the network was reorganized into eight "vertical" (north–south) and eight "horizontal" (east–west) high-speed corridors, almost doubling the network.

Eight Verticals

- Coastal corridor

- Beijing–Shanghai corridor

- Beijing–Hong Kong (Taipei) corridor

- Harbin–Hong Kong (Macau) corridor

- Hohhot–Nanning corridor

- Beijing–Kunming corridor

- Baotou (Yinchuan)–Hainan corridor

- Lanzhou (Xining)–Guangzhou corridor

Eight Horizontals

Service

[edit]

Rail operators

[edit]China Railway High-speed (CRH) is the high-speed rail service operated by state-owned China Railway, the national railway operator. Almost all high-speed rail lines, trainsets, and related services in China are owned and managed by China Railway under the CRH brand. The main exceptions are the Shanghai Maglev Train, which is operated by the Shentong Metro Group, and the Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link (XRL), which is jointly operated by China Railway and the Hong Kong-based MTR Corporation.

Although both classified as high-speed rail, the Shanghai Maglev often is not counted as part of the national high-speed rail network, while XRL is fully integrated into the national network of the CRH. China has the world's only commercial maglev high-speed train line in operation. The Shanghai Maglev Train, a turnkey Transrapid maglev demonstration line 30.5 km (19.0 mi) long. The trains have a top operational speed of 430 km/h (267 mph) and can reach a top non-commercial speed of 501 km/h (311 mph). It opened for operations in March 2004, and transports passengers between Shanghai's Longyang Road station and Shanghai Pudong International Airport. There have been numerous attempts to extend the line without success. A Shanghai-Hangzhou maglev line was also initially discussed but later shelved in favour of conventional high-speed rail.[122]

Two other Maglev lines, the Changsha Maglev and the Line S1 of Beijing, were designed for commercial operations with speeds lower than 120 km/h (75 mph).[123] The Fenghuang Maglev[124] opened in 2022 while the Qingyuan Maglev is under construction.[125]

Ridership

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: [79] 2008[126] 2010[127] 2011[128] 2014[129][130] 2015[131][132] 2016[133] 2017[134] 2018[135] 2019[136] 2020-2022[137] 2023[138] 2024 [139] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

China Railway reports the number of passengers carried by high-speed EMU train sets and this figure is frequently reported as high-speed ridership, even though this figure includes passengers from EMU trains providing sub-high speed service.[140] In 2007, CRH EMU trains running on conventional track upgraded in the sixth round of the "Speed-up Campaign" carried 61 million passengers, before the country's first high-speed rail line, the Beijing–Tianjin intercity railway, opened in August 2008.

In 2018, China Railway operated 3,970.5 pairs of passenger train service, of which 2,775 pairs were carried by EMU train sets.[140] Of the 3.313 billion passenger-trips delivered by China Railway in 2018, EMU train sets carried 2.001 billion passenger-trips.[140] This EMU passenger figure includes ridership from certain D- and C-class trains that are technically not within the definition of high-speed rail in China, as well as ridership from EMU train sets serving routes on conventional track or routes that combine high-speed track and conventional track.[140] Nevertheless, by any measure, high-speed rail ridership in China has grown rapidly with expansion of the high-speed rail network and EMU service since 2008.

China is the third country, after Japan and France, to have one billion cumulative HSR passengers. In 2018, annual ridership on EMU train sets, which encompasses officially defined high-speed rail service as well as certain sub-high-speed service routes, accounted for about two-thirds of all regional rail trips (not including urban trains) in China.[140] At the end of 2018, cumulative passengers delivered by EMU trains is reported to be over 9 billion.[140]

Safety

[edit]China's HSR network is regarded as one of the safest in the world.[141]: 70 The sole major accident to date was the Wenzhou train collision of July 23, 2011, which killed 40 people and injured 172.[142] The incident, attributed to flaws in newly designed signaling equipment,[143] prompted safety reforms. Since then, operations have maintained an exemplary safety record.[144]

Records

[edit]

Fastest trains in China

[edit]The "fastest" train commercial service can be defined alternatively by a train's top speed or average trip speed.

- The fastest commercial train service measured by peak operational speed is the Shanghai Maglev Train which can reach 431 km/h (268 mph). Due to the limited length of the Shanghai Maglev track 30 km (18.6 mi), the maglev train's average trip speed is only 245.5 km/h (152.5 mph). During testing in 2003, the maglev train achieved the Chinese record speed of 501 km/h (311 mph).[145]

- The fastest commercial train service measured by average train speed is the CRH express service on the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway, which reaches a top speed of 350 km/h (220 mph) and completes the 1,302 km (809 mi) journey between Shanghai Hongqiao and Beijing South, with two stops, in 4 hours and 24 min for an average speed of 291.9 km/h (181.4 mph), the fastest train service measured by average trip speed in the world.[146][147][148]

- The fastest timetabled start-to-stop runs between a station pair in the world are trains G27/G39 on the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway averaging 317.7 km/h (197.4 mph) running non-stop between Beijing South to Nanjing South before continuing to other destinations.[149]

- The top speed attained by a non-maglev train in China is 487.3 km/h (302.8 mph) by a CRH380BL train on the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway during a testing run on January 10, 2011.[150]

Longest service distance

[edit]The trains G403/404 and G405/406 for the Beijing West (Beijingxi) - Kunming South (Kunmingnan) service (distance 2,760 km (1,710 mi), travel time about 10 1/2 hours), which began service on January 1, 2017, became the longest high-speed rail service in the world.[151] It overtook the G529/530 trains for the Beijing West - Beihai service (2,697 km (1,676 mi), 15 1/2 hours for southbound train, 15 3/4 hours for northbound train), which had set the previous record on July 1, 2016.[152]

See also

[edit]- Rail transport in China

Media related to High-speed rail in China at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to High-speed rail in China at Wikimedia Commons High-speed rail in China travel guide from Wikivoyage

High-speed rail in China travel guide from Wikivoyage

Notes

[edit]- ^ Taiwan High Speed Rail is currently not under the jurisdiction of China Railways (CR) nor is it connected with CR's network. However, official CR news reports count Taiwan Area along with THSR in the figure.

- ^ Sichuan–Tibet railway is incorporated into the national high-speed rail service with the China Railway CR200J high-speed train.[7]

- ^ Zhuhai Station, which is served by the HSR network, is located parallel to the Mainland-Macau border, serving also as a de facto station for the land-constrained Macau.

- ^ According to Xinhua News Agency, the aggregate results of the six “Speed Up Campaigns” were: boosting passenger train speed on 22,000 km (14,000 mi) of tracks to 120 km/h (75 mph), on 14,000 km (8,700 mi) of tracks to 160 km/h (99 mph), on 2,876 km (1,787 mi) of tracks to 200 km/h (124 mph) and on 846 km (526 mi) of tracks to 250 km/h (155 mph).[37] According to China Daily, however, there were 6,003 km (3,730 mi) of tracks capable of 200 km/h (124 mph) in April 2007.[38]

- ^ On December 27, 2024, the Shanghai Metro opened the Airport Link Line, an intracity railway connecting Shanghai Hongqiao and Pudong airports. Operating at speeds up to 160km/h, the line reduced inter-airport travel time from over 90 minutes to under 40 minutes."Shanghai Airport Link Line train, Pudong, Hongqiao, Timetables, Fares".

Further reading

[edit]- Yan, Karl (2023). "Market-creating states: rethinking China's high-speed rail development". Review of International Political Economy.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Length of Beijing-HK rail network same as Equator". www.thestar.com.my. January 2022. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ^ Ma, Yujia (马玉佳). "New high-speed trains on drawing board- China.org.cn". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ^ Preston, Robert (3 January 2023). "China opens 4100km of new railway". International Railway Journal.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Martha; Bullock, Richard; Liu, Ziming (2019). China's High-Speed Rail Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4648-1425-9.

- ^ "Full speed ahead for China's high-speed rail network in 2019". South China Morning Post. 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- ^ "China builds the world's longest high-speed rail as a rail stalls in the U.S." finance.yahoo.com. 21 February 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-23.

- ^ "China-Tibet bullet trains to commence operations before July". Railway Technology. 8 March 2021.

- ^ "World's Longest Fast Train Line Opens in China". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Liu, Ziming G.; Lawrence, Martha B.; Bullock, Richard. "China's High-Speed Rail Development". World Bank. Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- ^ 庞巴迪:靠什么"赢在中国"——专访庞巴迪中国区总裁兼首席代表张剑炜 (in Chinese (China)). Worldrailway.com.cn. Retrieved 2011-08-17.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Japan Inc Shoots Itself on the Foot". Financial Times. 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ "Era of "Created in China"". Chinapictorial.com.cn. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ "China: A future on track". Xinkaishi.typepad.com. 2010-10-05. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ 汪玮 (2011-07-08). "China denies Japan's rail patent-infringement claims. On 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-07-25". China.org.cn. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ a b Shirouzu, Norihiko (2010-11-17). "Train Makers Rail Against China's High-Speed Designs". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- ^ Wines, Michael; Bradsher, Keith (2011-02-17). "China Rail Chief's Firing Hints at Trouble". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

Many multinational companies also resent China for tweaking foreign designs and building the equipment itself rather than importing it.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (2011-06-13). "High-Speed Trains in China to Run Slower, Ministry Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

In the past few months, some foreign companies that sold China its high-speed technology said the trains were not designed to operate at 215 miles per hour. The ministry said that Chinese engineers had improved on the foreign technology and that the trains were safe at the higher speeds.

- ^ Xin, Dingding (2011-06-28). "Full steam ahead for high-speed rail patents overseas". China Daily. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ^ "China's 'Super-Speed' Train Hits 500km". 2010-10-20. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Chinese firm launches R&D on 600 km/h maglev train". 2016-10-22. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ^ "China to step up testing on fastest-ever maglev train". South China Morning Post. 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ a b c d "CRRC unveils its 600 km/h high-speed maglev train". Railway Pro. 2025-07-17. Retrieved 2025-08-19.

- ^ Chen, Peng; Hua, Chen (2025). "Current Practices of Railway Ballastless Track Design Methods in China". Appl. Sci. 15 (10): 5621. doi:10.3390/app15105621.

- ^ Zhi-Ping; et al. (2022). "On the service performance of China's high-speed railway ballastless tracks". Int. J. Rail Transport Innovation. 6 (2): 123–140. doi:10.1093/iti/liac023.

- ^ "Indonesia to launch Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail, first in Southeast Asia". Jakarta Post. AFP. 1 October 2023.

- ^ Ibrahim, Achmad; Karmini, Niniek (2 October 2023). "Indonesian president launches Southeast Asia's first high-speed railway, funded by China". Associate Press.

- ^ Malleck, Julia (2 October 2023). "Why China laid the tracks for Indonesia's first high-speed rail".

- ^ Chinese Firm Constructs High-Speed Railway in Turkey 2014-01-18

- ^ Keith Bradsher (2010-04-08). "China Is Eager to Bring High-Speed Rail Expertise to the U.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- ^ a b Louise Young. Japan's Total Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press 1998. pp. 246–67.

- ^ "China's High-Speed Rail Dream" (PDF).

- ^ a b c 京沪高速铁路的论证历程大事记 (in Chinese). Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ 高铁时代. 中国国家地理网 (in Chinese (China)). 2010-04-07. Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ^ By the mid-1990s, average train speed in China was about 60 km/h (37 mph). (Chinese) "China plans five-year leap forward of railway development " Accessed 2006-09-30

- ^ 中国铁道部六次大提速. Sina News (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ "(Chinese)". News.cctv.com. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ 中国高铁"十一五"发展纪实:驶向未来 (in Chinese (China)). Xinhua News Agenc y. 2010-09-25. Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ^ Dingding, Xin (2007-04-18). "Bullet trains set to join fastest in the world". China Daily. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-05-09 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ a b "International Railway Journal – Rail And Rapid Transit Industry News Worldwide". Archived from the original on August 15, 2007.

- ^ MacLeod, Calum (June 1, 2011). "China slows its runaway high-speed rail expansion". USA Today. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ 铁道部官员深入解析:未来我国铁路布局. 中国经济网 (in Chinese (China)). 2009-01-19. Archived from the original on 2012-07-01. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- ^ (Chinese)[1] Accessed 2010-10-13

- ^ "Hundreds protest Shanghai maglev rail extension". Reuters. Jan 12, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Rail track beats Maglev in Beijing–Shanghai High Speed Railway". People's Daily. 2004-01-18. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ "Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Line, China". Railway-technology.com. 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ a b c d e f 中国式高铁的诞生与成长. Xinhua (in Chinese). March 4, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2010.

- ^ 日本等待中国'求婚' (in Chinese). 2003-08-06. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ "Violence flares as the Chinese rage at Japan" Guardian 2005-04-17

- ^ "High speed Train CRH1 – China" Bombardier Archived 2010-09-19 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-08-14

- ^ "Kawasaki Wins High-Speed Train Order for China" 2004–10 Archived June 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How Japan Profits From China's Plans" Forbes 2009-10-26

- ^ CRH5型动车组详细资料. 中国铁路网 (in Chinese). 2009-11-18. Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

- ^ "First Chinese designed HS train breaks cover". International Railway Journal. September 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ a b c d Bradsher, Keith (2010-02-12). "Keith Bradsher, "China Sees Growth Engine in a Web of Fast Trains"". The New York Times. China; United States. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "China to Bid on US High-Speed Rail Projects" A.P. March 13, 2010

- ^ a b Forsythe, Michael (2009-12-22). "Michael Forsythe "Letter from China: Is China's Economy Speeding Off the Rails?"". The New York Times. China. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ a b 2004年国家《中长期铁路网规划》内容简介 (in Chinese). 2014-05-27. Archived from the original on 2019-02-28. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "China's fastest high speed train 380A rolls off production line" Xinhua Archived 2010-05-30 at the Wayback Machine 2010-05-27

- ^ 网易 (2010-11-02). 时速380公里高速列车明年7月开行. 163.com (in Chinese (China)).

- ^ xinhuanet (2011-02-04). "High-speed rail broadens range of options for China's New Year travel". Archived from the original on February 9, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- ^ "Off the rails?". The Economist. 2011-03-31.

- ^ "China finds 187 mln yuan embezzled from Beijing-Shanghai railway project". News.xinhuanet.com. 2011-03-23. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ Moore, Malcolm (2011-08-01). "Chinese rail crash scandal: 'official steals $2.8 billion'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ "China acts on high-speed rail safety fears". Financial Times. 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "China Puts Brakes on High-Speed Trains" The Wall Street Journal 2011-04-17

- ^ "World's longest high-speed train to decelerate a bit". People's Daily Online. 2011-04-15.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (2011-07-24). "Train Wreck in China Heightens Unease on Safety Standards". The New York Times.

- ^ Watt, Louise (2011-07-25). "Crash raises doubts about China's fast rail plans". Washington Times. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ Martin Patience (2011-07-28). "China train crash: Signal design flaw blamed". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "China freezes new railway projects after high-speed train crash". Reuters. 2011-08-10. Archived from the original on 2011-08-17. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ^ "More high-speed trains slow down to improve safety|Society|chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn.

- ^ Rabinovitch, Simon (2011-10-27). "China's high-speed rail plans falter". China: Financial Times. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "China's high speed rail projects on hold due to cash crunch". Economic Times. 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ 中国铁路建设大规模停工 建设重点出现调整. International Business Times (in Chinese). 2011-10-26. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ 铁路工地一线直击:2700亿掀不起复工潮. Sohu Stocks (in Chinese). 2011-12-14. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ^ a b 揭秘:贵广高铁如何穿越喀斯特. 南方都市报 (in Chinese). 2014-12-26.

- ^ 陈清浩, "贵广高铁正式开通运营 从贵阳到广州4小时可达". 南方日报 (in Chinese). 2014-12-26.

- ^ Simon Rabinovitch, "China's high-speed rail gets back on track" Financial Times 2013-01-16

- ^ a b 铁路2014年投资8088亿元 超额完成全年计划. 人民网. 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ^ "China High Speed Train Development and Investment". The China Perspective. 2012-12-27. Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ^ "Sound financials recharge China's fast trains". marketwatch.com. 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2013-02-03.

- ^ "China's railways mileage tops 100,000 km" Xinhua 2013-12-28

- ^ 中国高铁版图再扩容:兰新、贵广、南广高铁今日开通. 中国新闻网 (in Chinese (China)). 2014-12-26.

- ^ a b 青荣城际今日通车 青烟威三城连心. 青岛新闻网 (in Chinese). Ifeng. 2014-12-28.

- ^ a b 12月10日起铁路再调图. Xinhua (in Chinese). 2014-11-15. Archived from the original on December 1, 2014.

- ^ 7月1日全国铁路再调图 增开动车组列车53对. 人民日报 (in Chinese). 2014-06-12.

- ^ a b c d 发改委再批复两城市铁路规划 总投资超2000亿. 中证网 (in Chinese). Sina Finance. 2014-12-22.

- ^ 郑州-重庆万州高铁获批 中部再添开发主轴. Sohu News (in Chinese). 2014-10-10.

- ^ 临沂至曲阜客运专线并轨京沪高铁获批 连云港至镇江高铁获批 预计2019年下半年通车. QQ Jiangsu (in Chinese). 2014-11-07. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- ^ 临沂至曲阜客运专线并轨京沪高铁获批. Sohu News (in Chinese). 2014-12-16.

- ^ 哈牡客运专线项目启动建设 打通亚欧国际货运大通道. 东北网 (in Chinese). 2014-12-18. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- ^ 浙江11条城际铁路线昨日获批 2020年前将全部建成 (in Chinese). 2014-12-18. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- ^ "Chinese Trainmakers To Merge And Form Export Powerhouse". Business Insider. AFP. 2014-12-03.

- ^ 中国高铁盈利地图:东部线路赚翻 中西部巨亏(图)-新华网. Xinhua (in Chinese (China)). 2016-08-02. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ "China's Busiest High-Speed Rail Line Makes a Fast Buck". Wall Street Journal. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ 中國高鐵"八縱八橫"線路確定 包含京台高鐵. Sina News (in Chinese).

- ^ 十年内高铁运营里程将翻倍 贯通特大城市可采用时速350公里标准. 每经网 (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- ^ chinanews. 2017年中国铁路投资8010亿元 投产新线3038公里-中新网. www.chinanews.com (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- ^ "China's high-speed rail lines top 37,900 at end of 2020 – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2021-01-10.

- ^ "China to Expand High-Speed Rail Network to 50,000 Kilometers by 2025". BrixSweden.org. 23 January 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Freeman, Will (2010-06-02). "Freeman & Kroeber, "Opinion: China's Fast Track to Development"". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ Ollivier, Gerald. "High-Speed Railways in China: A Look at Traffic" (PDF).

- ^ a b Bradsher, Keith (2009-01-22). "Keith Bradsher, "China's Route Forward"". The New York Times. China. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ China's amazing new bullet train CNN Money August 6, 2009

- ^ "Shanghai, Shenzhen, Beijing Lead Prospects in ULI's China Cities Survey". Urban Land Magazine. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ "China's high-speed-rail network and the development of second-tier cities". JournalistsResource.org, retrieved Feb. 20, 2014.

- ^ "Japan Inc shoots itself in foot on bullet train". Ft.com. 2010-07-08. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ^ "China Railway's debt nears $900bn under expansion push".

- ^ 高铁盈利地图:东部赚翻 中西部普遍巨亏. Sina Finance (in Chinese (China)). 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ Spegele, Brian (21 November 2024). "China Is Building 30,000 Miles of High-Speed Rail—That It Might Not Need". WSJ.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (25 August 2024). "China's ghost stations show a nation haunted by debt". www.thetimes.com.

- ^ a b c Staff (11 January 2024). "China's 450km/h high-speed CR450 train to be tested this year, set to enter service by 2025". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Bai, Yujie; Lu, Yutong (1 April 2021). "China looks to slow growth of struggling high-speed rail". Nikkei Asia.

- ^ 铁路建设9成缺钱停工 多地高铁项目拖欠工人工资停工. 中国经营网 (in Chinese). 2011-10-26.

- ^ 铁道部有意打包高铁资产 成立资产管理公司. 中财网 (in Chinese). 2010-09-25. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- ^ 不计建设投资 京津高铁今年持平. 经济观察报 (in Chinese). Ifeng. 2010-09-18.

- ^ "谨防高铁灰犀牛". finance.sina.com.cn. January 28, 2019.

- ^ Beck, Bente, Schilling, Arne, Heiner, Martin (May 2013). "Railway Efficiency – An Overview and a Look at Opportunities for Improvement" (PDF). International Transport Forum.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zhao, Yuanfei (Scott) (2025-08-20). "How high-speed rail is reshaping Chinese regional air travel". Cirium Thought Cloud. Retrieved 2025-09-14.

- ^ "China's operating high-speed railway to hit 60,000 km by 2030". China Daily. January 3, 2025.

- ^ "China's rail network continued to break records in 2024".

- ^ "No timetable yet for Shanghai-Hangzhou maglev line: official". Xinhua News Agency. March 23, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Beijing's first maglev line resumes construction". China Daily. April 22, 2015.

- ^ 严茂强. "Maglev line opens to tourists in Fenghuang". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "All Existing and U/C Maglev Lines in 2020". MaglevNET. January 9, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ 世界银行:中国高铁作为出行新选择快速发展. www.shihang.org (in Simplified Chinese). 2014-12-19.

- ^ 把脉中国高铁发展计划:高铁运行头三年 (PDF). worldbank.org (in Simplified Chinese). 2012-02-01.

- ^ F_404. "High-speed rail construction not suspended – People's Daily Online". en.people.cn.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Error" 中国高速铁路: 运量分析 (PDF) (in Chinese). World Bank. December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-21. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ^ 铁路2014年投资8088亿元 超额完成全年计划-财经-人民网. people.com.cn (in Chinese). 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ^ 新华网_让新闻离你更近. Xinhua (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on July 22, 2016.

- ^ "China Railway sets out 2017 targets – International Railway Journal". 4 January 2017.

- ^ "China Exclusive: Five bln trips made on China's bullet trains". Xinhua English. 2016-07-21. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016.

- ^ chinanews. 2017年中国铁路投资8010亿元 投产新线3038公里-中新网. www.chinanews.com (in Chinese (China)).

- ^ 中国铁路2018年成绩:旅客发送量33.7亿人次 货物发送量40.22亿吨. 央视财经 (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ "China's railways report 3.57b passenger trips in 2019". China Daily. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- ^ Luk, Glenn (2023-04-12). "charts & data | 2023.04.12". reading, writing & investing. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ "2024年中国高铁行业研究报告 - 21经济网". www.21jingji.com. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ "国家铁路局:2024年1—12月份全国铁路客货运量均创历史同期新高_国家铁路局". January 18, 2025. Archived from the original on 2025-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f 中国高铁动车组发送旅客90亿人次:2018年占比超60%. Ifeng News (in Chinese (China)). 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ Garlick, Jeremy (2024). Advantage China: Agent of Change in an Era of Global Disruption. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-350-25231-8.

- ^ 国务院处理温州动车追尾事故54名责任人_新闻中心_新浪网. Sina News (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ Ollivier, Gerald; Sondhi, Jitendra; Zhou, Nanyan (July 2014). "High-Speed Railways in China: A Look at Construction Costs" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved Apr 22, 2024.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (2013-09-23). "Despite a Deadly Crash, Rail System Has Good Safety Record". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ "Shanghai Maglev Train (431 km/h) - High Definition Video". shanghaichina.ca.

- ^ 京沪高铁明提速 "复兴号"将在中途超车"和谐号". Caixin Companies (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ "China restores bullet train speed to 350 km/h – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ "China begins to restore 350 kmh bullet train – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ "China powers ahead as new entrants clock in" (PDF). Railway Gazette International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-09. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- ^ 中国北车刷新高铁运营试验世界纪录速度(图)-搜狐证券 (in Chinese (China)). Sohu Stocks. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ^ "China launches longest high-speed train service" China Daily 2017-01-05

- ^ 北京西至北海将开通全国运行里程最长动车. 中国青年报 (in Chinese (China)). Sina News. 2016-06-15.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to High-speed rail in China at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to High-speed rail in China at Wikimedia Commons