Chikungunya

| Chikungunya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rash from chikungunya | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, and rash.[2] |

| Complications | Long term joint pain[2] |

| Usual onset | 2 to 14 days after exposure[3] |

| Duration | Usually less than a week[2] |

| Causes | Chikungunya virus spread by mosquitoes[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test for viral RNA or antibodies[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Dengue fever, Zika fever[3] |

| Prevention | Chikungunya vaccine, Mosquito control, avoidance of bites[4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[3] |

| Prognosis | Risk of death ~ 1 in 1,000[4] |

| Frequency | > 1 million (2014)[3] |

Chikungunya is an infection caused by the chikungunya virus.[3] The most common symptoms are fever and joint pain,[2] typically occurring four to eight days after the bite of an infected mosquito;[3] however some people may be infected without showing any symptoms.[5] Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, and a rash.[2] Symptoms usually improve within a week; however, occasionally the joint pain may last for months or years.[2][6] The very young, old, and those with other health problems are at risk of more severe disease.[2]

The virus is spread between people by two species of mosquito in the genus Aedes: Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti,[3] which mainly bite during the day,[7][8] particularly around dawn and in the late afternoon.[9] The virus may circulate within a number of animals, including birds and rodents.[3] Diagnosis is done by testing the blood for either viral RNA or antibodies to the virus.[3] The symptoms can be mistaken for those of dengue fever and Zika fever, which are spread by the same mosquitoes.[3] It is believed most people become immune after a single infection.[2]

The best means of prevention are overall mosquito control and the avoidance of bites in areas where the disease is common.[4] This may be partly achieved by decreasing mosquitoes' access to water, as well as the use of insect repellent and mosquito nets. Chikungunya vaccines have been approved for use in the United States and in the European Union.[10][11][12] No specific treatment for chikungunya is available; supportive care is recommended, with symptomatic treatment of fever and joint swelling.[4]

The chikungunya virus is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions where warm climates and abundant populations of its mosquito vectors (A. aegypti and A. albopictus) facilitate its transmission.[3] The disease was first identified in 1952 in Tanzania and named based on the Makonde words for "to become contorted".[3] The disease has spread widely since the 2000s with outbreaks reported in many tropical and some temperate areas. It is considered to be endemic in many parts of the world,[3][13] affecting millions of people every year.[14][15] Chikungunya has become a global health concern due to its rapid geographic expansion, recurrent outbreaks, the lack of effective antiviral treatments, and potential to cause severe symptoms and death.[16]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Chikungunya can be asymptomatic, with estimates of between 17% and 40% of infections showing no symptoms.[5] For those experiencing symptoms, they typically begin with a sudden high fever above 39 °C (102 °F) around 3 to 7 days after the bite of an infected mosquito.[17][5] The fever is often accompanied by severe muscle and joint pain, which affects multiple joints in the arms and legs and is often symmetric – i.e. if one elbow is affected, the other is as well.[18][5] People with chikungunya also frequently experience headaches, back pain, nausea, and fatigue.[18] Around half of those affected develop a rash, with reddening and sometimes small bumps on the palms, foot soles, torso, and face.[18]

For some, the rash remains constrained to a small part of the body; for others, the rash can be extensive, covering more than 90% of the skin.[17] Some people experience gastrointestinal issues, with abdominal pain and vomiting. Others experience eye problems, namely sensitivity to light, conjunctivitis, and pain behind the eye.[18] This first set of symptoms – called the "acute phase" of chikungunya – lasts around a week, after which most symptoms resolve on their own.[18]

For those with severe symptoms, approximately 30% to 40% continue to have symptoms after the "acute phase" resolves.[5][18] The lasting symptoms tend to be joint pains: arthritis, tenosynovitis, and/or bursitis.[18] If the affected person has pre-existing joint issues, these tend to worsen.[18] Overuse of a joint can result in painful swelling, stiffness, nerve damage, and neuropathic pain.[18] Typically the joint pain improves with time; however, the chronic stage can last anywhere from a few months to several years.[18]

Almost all symptomatic cases feature joint pain, generally in more than one joint.[19] Pain most commonly occurs in peripheral joints, such as the wrists, ankles, and joints of the hands and feet as well as some of the larger joints, typically the shoulders, elbows and knees.[19][20] Joints are more likely to be affected if they have previously been damaged by disorders such as arthritis.[20] Pain may also occur in the muscles or ligaments. In more than half of cases, normal activity is limited by significant fatigue and pain.[19] Infrequently, inflammation of the eyes may occur in the form of iridocyclitis, or uveitis, and retinal lesions may occur.[21] Temporary damage to the liver may occur.[22]

People with chikungunya occasionally develop long term neurologic disorders, most frequently swelling or degeneration of the brain, inflammation or degeneration of the myelin sheaths around neurons, Guillain–Barré syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, hypotonia (in newborns), and issues with visual processing.[18]

Newborns, the elderly, and those with diabetes, heart disease, liver and kidney diseases, and human immunodeficiency virus infection tend to have more severe cases of chikungunya. Fewer than 1 in 1,000 people with symptomatic chikungunya die of the disease; generally these are people with pre-existing health conditions.[18][5]

Transmission

[edit]Chikungunya is generally transmitted from mosquitoes to humans. Chikungunya is spread through bites from Aedes mosquitoes, specifically A. aegypti (Egyptian mosquito) and A. albopictus (Tiger mosquito).[3] Because high amounts of virus are present in the blood during the first few days of infection, the virus can spread from an infected human to a mosquito, where it replicates without harming the mosquito. Subsequently, a bite from the infected mosquito will transmit the virus back to a human.[3] The incubation period ranges from one to twelve days and is most typically three to seven.[19]

Rarely, the disease can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy or at birth, in women who become infected a few days before delivery.[5]

Mechanism

[edit]Chikungunya virus is passed to humans when a bite from an infected mosquito breaks the skin and introduces the virus into the body. The virus initially replicates in cells near the location of the bite; from here it enters the lymphatic system and the bloodstream, enabling it to circulate to organs and tissues which become infected. Most frequently it reproduces in the lymphatic system and the spleen, as well as peripheral joints, muscles and tendons where symptoms frequently occur; it appears that the virus is able to penetrate and replicate in many different types of cells.[23] In severe cases it can infect the brain and liver.[24][23]

During the acute phase of infection, large numbers of infectious virus particles are present in the bloodstream, making it very likely that an uninfected mosquito will pick up the virus if it bites the human host.[24][23]

During the first few days of infection, the host's innate immune system is activated, producing type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines to fight the infection. This generates the fever and localised inflammation which is characteristic of the disease.[23][25] It takes about a week before the host's adaptive immune system begins to develop antibodies which eventually clear the virus from the bloodstream.[26] However the virus can persist within specific tissues, especially the joints, causing long term inflammation and pain in chronic cases.[25]

The virus has mechanisms which help it to evade the immune response. Within an infected cell, the viral nonstructural protein 2 (nsP2) interferes with the JAK-STAT signalling pathway to hinder it from triggering an antiviral response.[27] The virus can induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) in host cells; virus laden debris from apoptosis is engulfed by macrophages which in turn become infected.[25] The virus also seems to be able to evade T lymphocytes which seek to target and destroy the virus particles.[28]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosing chikungunya can be difficult because its symptoms, such as sudden fever and joint pain, closely resemble other mosquito-borne illnesses like dengue fever and malaria.[29] Chikungunya should be suspected if a patient with these symptoms either lives in an area where the virus is endemic, or if they have recently traveled to such an area.[29][30]

During the first week of illness, when virus is present in the bloodstream, it is possible to detect viral RNA in a blood sample using techniques such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or viral culture.[30] After this time, the body develops antibodies and the virus is eliminated from the bloodstream. Antibodies in blood serum persist for between 3 and 12 months; they can be detected for up to a year after infection using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA).[29][18] All of these techniques are time consuming and costly, requiring sophisticated laboratory equipment which may not be available in resource poor settings.[31]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]The Aedes mosquitoes which carry chikungunya virus can also carry other viruses such as dengue, zika, and yellow fever.[32] Other infections which should be considered include malaria, leptospirosis, measles, mononucleosis and African tick bite fever, which are often endemic in the same areas and can have similar symptoms. It is possible for a patient to be infected by more than one virus simultaneously.[29]

Prevention

[edit]

Although an approved vaccine exists, the most effective means of prevention is to avoid or prevent mosquito bites. The main strategies for this are: controlling mosquito populations by limiting their habitat; and protection against contact with disease-carrying mosquitoes.[4] On a large scale, mosquito control focuses on eliminating standing water where mosquitoes lay eggs and develop as larvae.[33] Individuals should use mosquito repellent, as well as barriers such as loose clothing that covers the arms and legs, mosquito nets and window and door screens.[34]

Once immunity against chikungunya has been acquired, whether as a result of infection or vaccination, it endures long term and may be lifelong.[5][35]

Vaccination

[edit]

Chikungunya vaccines are vaccines intended to provide acquired immunity against the chikungunya virus.[36][37] As of 2025[update], two vaccines have been licensed in some countries. These are Ixchiq, a live attenuated vaccine from Valneva, and Vimkunya manufactured by Bavarian Nordic which utilises virus-like particle technology.[38][39][40][41]

The most commonly reported side effects of Ixchiq include tenderness at the injection site, as well as headache, fatigue, muscle pain, joint pain, fever, and nausea.[39] However the license for Ixchiq has been suspended or restricted in some countries due to the risk of severe side effects, particularly in older people.[42][43]Treatment

[edit]No specific treatment for chikungunya is available.[4] Supportive care is recommended, and symptomatic treatment of fever and joint swelling includes the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen), rest, and fluids.[4][5] Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen should not be used in the acute phase until dengue fever has been ruled out, as these can increase the risk of bleeding in dengue.[3][29]

Chronic symptoms, especially joint pain, may persist for months after the infection has passed. The pain and swelling may be treated with NSAIDs or in more severe cases with corticosteroid drugs or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs such as hydroxychloroquine.[29][44]

Prognosis

[edit]The mortality rate of chikungunya is slightly less than 1 in 1000.[45] Those over the age of 65, infants, and those with underlying chronic medical problems are most likely to have severe complications.[46] Newborn infants are especially vulnerable as they lack fully developed immune systems, and may pick up the infection through vertical transmission from their mother.[46] The likelihood of prolonged symptoms or chronic joint pain is increased with increased age and prior rheumatological disease.[47][48]

Epidemiology

[edit]

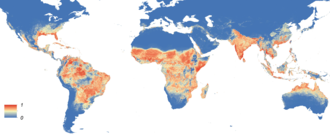

Chikungunya virus is transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito of the genus Aedes, specifically Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus.[3] A. aegypti, the so-called Egyptian mosquito, is well adapted to urban settings in the tropics but has poor tolerance for low temperatures and is less able to overwinter in temperate climates. A. albopictus, the Asian Tiger mosquito, has a wider temperature tolerance and can overwinter as eggs in temperate regions. Both mosquitoes have spread from their ancestral ranges into tropical, sub-tropical, and some temperate regions of the Americas, Africa, Australasia and Eurasia.[49][50]

In Africa, chikungunya virus is maintained by a sylvatic cycle in which the virus cycles between small mammals (principally non-human primates), and mosquitos; humans can be infected by a mosquito bite but the virus does not rely on humans for survival.[51] Elsewhere, chikungunya is maintained in an urban cycle in densely populated areas. In this, an infected mosquito bites a human, transmitting the virus which replicates in the human host; a few days later, large numbers of infective virus particles are present in the host's bloodstream. When another mosquito bites the infected human, it picks up the virus, and this cycle continues.[52]

As of December 2024[update], 119 countries and territories, principally those in tropical and subtropical regions, have reported local transmission of chikungunya.[53] In some of these it is endemic (continually present). In some regions the disease tends to manifest as periodic epidemics which can be sudden and intense, as the virus spreads among a population with a low level of herd immunity.[15][23] Because of the difficulty in reliably diagnosing chikungunya disease, especially in resource poor contexts, there are no reliable statistics on its incidence. However epidemiological modelling studies estimate between 14.4 million[14] and 35 million people[15] are infected annually. Up to 848,000 people experience chronic long-term pain; annual mortality is estimated at up to 3,700 deaths.[15]

History

[edit]The term chikungunya is derived from the Makonde root verb kungunyala, meaning to dry up or become contorted, descriptive of the posture of people with chronic symptoms.[54] The disease was first clearly described by Marion Robinson[55] and W.H.R. Lumsden[54] in a pair of 1955 papers, following an outbreak in 1952 on the Makonde Plateau, along the border between Mozambique and Tanganyika (the mainland part of modern-day Tanzania).[54] The virus itself was isolated in 1955.[56] At that time, it was endemic to sub-saharan Africa, relying on A. aegypti to maintain its sylvatic cycle.[51] Prior to this, the disease may have caused sporadic epidemics in other regions, which had been incorrectly ascribed to dengue.[57][58][59]

The first direct evidence of chikungunya spreading outside of Africa came from Bangkok, Thailand, in 1958, during an urban outbreak. It subsequently appeared in India and Cambodia in the early 1960s, associated with the spread of the A. aegypti mosquito to those regions.[60]

An outbreak on the coast of Kenya in 2004 rapidly spread to the islands of the Indian Ocean (such as La Réunion) in 2005, then to India and Southeast Asia where it caused explosive outbreaks affecting millions of people.[61] Infected air travelers carried the virus into areas where the population had not previously been exposed to the disease and had no immunity.[33]

An analysis of the genetic code of chikungunya virus suggests that the wider spread of the disease since 2004 may be due to a genetic change which altered the E1 segment of the virus' viral coat protein, a variant called E1-A226V. Prior to this mutation, spread of the virus was restricted by the relatively narrow geographical range of its principal vector, A. aegypti. The adaptive effect of this mutation is that the virus became able to use A albopictus as a vector, spreading within its wider geographical range.[62][63] A. albopictus is an invasive species which since the 1960's has spread through parts of Europe, the Americas, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East.[64]

Chikungunya was introduced to the Americas in 2013, first detected on the French island of Saint Martin,[65][23] and over the next four years more than 2.6 million cases were recorded in this region.[66]

Research

[edit]Chikungunya is recognised as a global threat; there are an estimated 35 million cases annually, with 2.8 billion people living in areas which are threatened by the disease.[67] It is classed as a priority pathogen by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).[68]

Research on chikungunya focuses on improving knowledge of the mechanism of the disease and developing tools for its prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

- Prevention of chikungunya is principally focused on the development and testing of vaccines. As of 2025[update], two vaccines are available; each of them gives long lasting protection after administration of a single dose.[69] Other vaccine candidates are under development.[70]

- Reliable diagnosis of chikungunya is difficult, slow and expensive. Research is under way to develop diagnostic tools which are cheaper, quicker and easier to use.[31][71]

- There is no effective antiviral treatment for chikungunya. Research directions include repurposing some existing licenced drugs[72] and modifying plant-derived compounds.[73]

- For many, the sequelae of chikungunya can persist for month or years, and range from mild discomfort to severe and debilitating joint pain which severely affects their physical and mental well being. Research in to the underlying mechanism of long term pain, and its possible treatments, is ongoing.[74][75]

Chikungunya virus

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into a new article titled Chikungunya virus. (Discuss) (October 2025) |

Virology

[edit]| Chikungunya virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chikungunya virus structure at atomic resolution. Bar = 100 Å[76] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Martellivirales |

| Family: | Togaviridae |

| Genus: | Alphavirus |

| Species: | Alphavirus chikungunya

|

Chikungunya virus is a member of the genus Alphavirus, and family Togaviridae. Chikungunya virus features an icosahedral capsid surrounded by a lipid envelope, with a diameter ranging from 60 to 70 nm.[77] It was first isolated in 1953 in Tanzania and is an RNA virus with a positive-sense single-stranded genome of about 11.6kb.[78] It is a member of the Semliki Forest virus complex and is closely related to Ross River virus, O'nyong'nyong virus, and Semliki Forest virus.[79] Because it is transmitted by arthropods, namely mosquitoes, it can also be referred to as an arbovirus (arthropod-borne virus). In the United States, it is classified as a category B priority pathogen,[80] and work requires biosafety level III precautions.[81]

Three genotypes of this virus have been described, each with a distinct genotype and antigenic character: West African, East/Central/South African, and Asian genotypes.[82] The Asian lineage originated in 1952 and has subsequently split into two lineages – India (Indian Ocean Lineage) and South East Asian clades. This virus was first reported in the Americas in 2014. Phylogenetic investigations have shown two strains in Brazil – the Asian and East/Central/South African types – and that the Asian strain arrived in the Caribbean (most likely from Oceania) in about March 2013.[83] The rate of molecular evolution was estimated to have a mean rate of 5 × 10−4 substitutions per site per year (95% higher probability density 2.9–7.9 × 10−4).[83]

The chikungunya virus genome encodes both structural and non-structural proteins as typical of alphavirus genomic organization.[84] The structural proteins, including the capsid, E3, E2, 6K and E1, are responsible for encapsulating the viral genome and assembling new viral particles. These proteins are critical for viral entry into host cells. Meanwhile, the non-structural proteins, nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4, play essential roles in viral replication, translation, and immune evasion.[84]

Viral replication

[edit]

The virus consists of four nonstructural proteins and three structural proteins.[60] The structural proteins are the capsid and two envelope glycoproteins: E1 and E2, which form heterodimeric spikes on the viron surface. E2 binds to cellular receptors in order to enter the host cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. E1 contains a fusion peptide which, when exposed to the acidity of the endosome in eukaryotic cells, dissociates from E2 and initiates membrane fusion that allows the release of nucleocapsids into the host cytoplasm, promoting infection.[85] The mature virion contains 240 heterodimeric spikes of E2/E1, which after release, bud on the surface of the infected cell, where they are released by exocytosis to infect other cells.[78]

References

[edit]- ^ "chikungunya". Oxford Learner's Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h CDC (15 May 2024). "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Chikungunya Fact Sheet (2025)". World Health Organization. 14 April 2025. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Caglioti C, Lalle E, Castilletti C, Carletti F, Capobianchi MR, Bordi L (July 2013). "Chikungunya virus infection: an overview". The New Microbiologica. 36 (3): 211–27. PMID 23912863.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Chikungunya – Fact sheet". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). 24 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

- ^ van Aalst M, Nelen CM, Goorhuis A, Stijnis C, Grobusch MP (1 January 2017). "Long-term sequelae of chikungunya virus disease: A systematic review". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 15: 8–22. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.01.004. ISSN 1477-8939. PMID 28163198.

- ^ Paixão ES, Teixeira MG, Rodrigues LC (2018). "Zika, chikungunya and dengue: the causes and threats of new and re-emerging arboviral diseases". BMJ Global Health. 3 (Suppl 1) e000530. Bibcode:2018BMJGH...300530P. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000530. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 5759716. PMID 29435366.

- ^ "Preventing Chikungunya". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 February 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ AFP (23 July 2025). "Outbreak of Chikungunya Virus Poses Global Risk, Warns WHO". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 24 July 2025.

- ^ "Ixchiq EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 30 May 2024. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Vimkunya EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 30 January 2025. Retrieved 16 February 2025.>

- ^ "FDA Approval". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 9 November 2023. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "Information for travellers to areas with chikungunya transmission". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2025.

- ^ a b Kang H, Lim A, Auzenbergs M, Clark A, Colón-González FJ, Salje H, et al. (October 2025). "Global, regional and national burden of chikungunya: force of infection mapping and spatial modelling study". BMJ Global Health. 10 (10) e018598. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2024-018598. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 12506043. PMID 41033690.

- ^ a b c d Ribeiro dos Santos G, Jawed F, Mukandavire C, Deol A, Scarponi D, Mboera LE, et al. (July 2025). "Global burden of chikungunya virus infections and the potential benefit of vaccination campaigns". Nature Medicine. 31 (7): 2342–2349. doi:10.1038/s41591-025-03703-w. ISSN 1546-170X. PMC 12283390. PMID 40495015.

- ^ Moizéis RN, Fernandes TA, Guedes PM, Pereira HW, Lanza DC, Azevedo JW, et al. (19 May 2018). "Chikungunya fever: a threat to global public health". Pathogens and Global Health. 112 (4): 182–94. doi:10.1080/20477724.2018.1478777. ISSN 2047-7724. PMC 6147074. PMID 29806537.

- ^ a b Burt FJ, Chen W, Miner JJ, Lenschow DJ, Merits A, Schnettler E, et al. (1 April 2017). "Chikungunya virus: an update on the biology and pathogenesis of this emerging pathogen". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (4): e107 – e117. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30385-1. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 28159534.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Vairo F, Haider N, Kock RA, Ntoumi F, Ippolito G, Zumla A (25 October 2019). "Chikungunya: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, Management, and Prevention (Full text download)". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 33 (4): 1003–1025. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.08.006. ISSN 0891-5520. PMID 31668189.

- ^ a b c d Thiberville SD, Moyen N, Dupuis-Maguiraga L, Nougairede A, Gould EA, Roques P, et al. (1 September 2013). "Chikungunya fever: Epidemiology, clinical syndrome, pathogenesis and therapy". Antiviral Research. 99 (3): 345–70. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.009. ISSN 0166-3542. PMC 7114207. PMID 23811281.

- ^ a b Burt FJ, Rolph MS, Rulli NE, Mahalingam S, Heise MT (February 2012). "Chikungunya: a re-emerging virus". Lancet. 379 (9816): 662–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60281-X. PMID 22100854. S2CID 33440699.

- ^ Mahendradas P, Ranganna SK, Shetty R, Balu R, Narayana KM, Babu RB, et al. (February 2008). "Ocular manifestations associated with chikungunya". Ophthalmology. 115 (2): 287–91. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.085. PMID 17631967.

- ^ Simon F, Javelle E, Oliver M, Leparc-Goffart I, Marimoutou C (June 2011). "Chikungunya virus infection". Current Infectious Disease Reports. 13 (3): 218–28. doi:10.1007/s11908-011-0180-1. PMC 3085104. PMID 21465340.

- ^ a b c d e f Silva LA, Dermody TS (1 March 2017). "Chikungunya virus: epidemiology, replication, disease mechanisms, and prospective intervention strategies". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 127 (3): 737–749. doi:10.1172/JCI84417. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 5330729. PMID 28248203.

- ^ a b Vu DM, Jungkind D, Angelle Desiree LaBeaud (1 June 2017). "Chikungunya Virus". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. Emerging Pathogens. 37 (2): 371–382. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.01.008. ISSN 0272-2712. PMC 5469677. PMID 28457355.

- ^ a b c Srivastava P, Kumar A, Hasan A, Mehta D, Kumar R, Sharma C, et al. (28 April 2020). "Disease Resolution in Chikungunya—What Decides the Outcome?". Frontiers in Immunology. 11 695. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00695. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 7198842. PMID 32411133.

- ^ CDC (20 August 2025). "Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Chikungunya Virus Disease". Chikungunya Virus. Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ Fros JJ, Liu WJ, Prow NA, Geertsema C, Ligtenberg M, Vanlandingham DL, et al. (15 October 2010). "Chikungunya Virus Nonstructural Protein 2 Inhibits Type I/II Interferon-Stimulated JAK-STAT Signaling". Journal of Virology. 84 (20): 10877–10887. doi:10.1128/jvi.00949-10. PMC 2950581. PMID 20686047.

- ^ Davenport BJ, Bullock C, McCarthy MK, Hawman DW, Murphy KM, Kedl RM, et al. (16 April 2020). "Chikungunya Virus Evades Antiviral CD8+ T Cell Responses To Establish Persistent Infection in Joint-Associated Tissues". Journal of Virology. 94 (9): 10.1128/jvi.02036–19. doi:10.1128/jvi.02036-19. PMC 7163133. PMID 32102875.

- ^ a b c d e f Ojeda Rodriguez JA, Haftel A, Walker II (2025), "Chikungunya Fever", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30480957, retrieved 30 October 2025

- ^ a b CDC (15 May 2024). "About Chikungunya". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ a b Silva Ld, Costa LH, Dos Santos IC, de Curcio JS, Barbosa AM, Anunciação CE, et al. (1 February 2024). "Advancing Chikungunya Diagnosis: A Cost-Effective and Rapid Visual employing Loop-mediated isothermal reaction". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 108 (2): 116111. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2023.116111. ISSN 0732-8893. PMID 38016385.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ Abbasi E (1 March 2025). "Global expansion of Aedes mosquitoes and their role in the transboundary spread of emerging arboviral diseases: A comprehensive review". IJID One Health. 6 100058. doi:10.1016/j.ijidoh.2025.100058. ISSN 2949-9151.

- ^ a b Weaver SC, Lecuit M (March 2015). "Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (13): 1231–39. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1406035. PMID 25806915.

- ^ "Mosquito bite avoidance: advice for travellers". UK Health Security Agency. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2025.

- ^ "What Is Chikungunya?". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 14 September 2025. Retrieved 11 November 2025.

- ^ "Ixchiq". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 9 November 2023. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Vimkunya". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 October 2024. Archived from the original on 4 March 2025. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "NaTHNaC - Chikungunya". National Travel Health Network and Centre. 14 April 2025. Retrieved 12 November 2025.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves First Vaccine to Prevent Disease Caused by Chikungunya Virus". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 9 November 2023. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Ixchiq EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 30 May 2024. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ "Vimkunya EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 30 January 2025. Archived from the original on 16 February 2025. Retrieved 16 February 2025. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ CDC (22 August 2025). "Chikungunya Vaccine Information for Healthcare Providers". Chikungunya Virus. Retrieved 12 November 2025.

As of Friday, August 22, 2025, FDA suspended the U.S. license for IXCHIQ, the live-attenuated chikungunya vaccine.

- ^ "IXCHIQ Chikungunya vaccine: temporary suspension in people aged 65 years or older". GOV.UK. 18 June 2025. Retrieved 12 November 2025.

The Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) has temporarily restricted use of the IXCHIQ Chikungunya vaccine in people aged 65 years and over following very rare fatal reactions reported globally.

- ^ Pathak H, Mohan MC, Ravindran V (1 September 2019). "Chikungunya arthritis". Clinical Medicine. 19 (5): 381–385. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2019-0035. ISSN 1470-2118. PMC 6771335. PMID 31530685.

- ^ Mavalankar D, Shastri P, Bandyopadhyay T, Parmar J, Ramani KV (March 2008). "Increased mortality rate associated with chikungunya epidemic, Ahmedabad, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (3): 412–15. doi:10.3201/eid1403.070720. PMC 2570824. PMID 18325255.

- ^ a b Morrison TE (October 2014). "Reemergence of chikungunya virus". Journal of Virology. 88 (20): 11644–47. doi:10.1128/JVI.01432-14. PMC 4178719. PMID 25078691.

- ^ Schilte C, Staikowsky F, Staikovsky F, Couderc T, Madec Y, Carpentier F, et al. (2013). "Chikungunya virus-associated long-term arthralgia: a 36-month prospective longitudinal study". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (3) e2137. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002137. PMC 3605278. PMID 23556021.

- ^ Gérardin P, Fianu A, Michault A, Mussard C, Boussaïd K, Rollot O, et al. (January 2013). "Predictors of Chikungunya rheumatism: a prognostic survey ancillary to the TELECHIK cohort study". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 15 (1) R9. doi:10.1186/ar4137. PMC 3672753. PMID 23302155.

- ^ "Aedes aegypti - Factsheet for experts". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2025.

- ^ "Aedes albopictus - Factsheet for experts". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2025.

- ^ a b Powers AM, Logue CH (September 2007). "Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus". The Journal of General Virology. 88 (Pt 9): 2363–77. doi:10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. PMID 17698645.

- ^ Shandhi SS, Malaker S, Shahriar M, Anjum R (1 November 2025). "Chikungunya virus: from genetic adaptation to pandemic risk and prevention". Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease. 12 20499361251371110. doi:10.1177/20499361251371110. ISSN 2049-9361. PMC 12398651. PMID 40893869.

- ^ "Chikungunya epidemiology update - June 2025 (pdf download)". World Health Organization. 11 June 2025. Retrieved 16 November 2025.

- ^ a b c Lumsden WH (January 1955). "An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. II. General description and epidemiology". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 49 (1): 33–57. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(55)90081-X. PMID 14373835.

- ^ Robinson MC (January 1955). "An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 49 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. PMID 14373834.

- ^ Ross RW (June 1956). "The Newala epidemic: III. The virus: isolation, pathogenic properties and relationship to the epidemic". Epidemiology & Infection. 54 (2): 177–191. doi:10.1017/S0022172400044442. ISSN 0022-1724. PMC 2218030. PMID 13346078.

- ^ Rathore MH, Runyon J, Haque Tu (1 August 2017). "Emerging Infectious Diseases". Advances in Pediatrics. 64 (1): 27–71. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2017.04.002. ISSN 0065-3101. PMID 28688593.

- ^ Carey DE (July 1971). "Chikungunya and dengue: a case of mistaken identity?". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 26 (3): 243–62. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXVI.3.243. PMID 4938938.

- ^ Morens DM, Fauci AS (4 September 2014). "Chikungunya at the Door — Déjà Vu All Over Again?". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (10): 885–887. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1408509. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 25029435.

- ^ a b Weaver SC, Forrester NL (1 August 2015). "Chikungunya: Evolutionary history and recent epidemic spread". Antiviral Research. 120: 32–39. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.04.016. ISSN 0166-3542. PMID 25979669.

- ^ Soumahoro MK, Boelle PY, Gaüzere BA, Atsou K, Pelat C, Lambert B, et al. (14 June 2011). "The Chikungunya Epidemic on La Réunion Island in 2005–2006: A Cost-of-Illness Study". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5 (6) e1197. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001197. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3114750. PMID 21695162.

- ^ Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S (December 2007). "A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (12) e201. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. PMC 2134949. PMID 18069894.

- ^ Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, et al. (July 2006). "Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak". PLOS Medicine. 3 (7) e263. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. PMC 1463904. PMID 16700631.

- ^ "Global Invasive Species Database". The International Union for Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ Charles J (1 June 2014). "Mosquito-borne virus knocking on Fla.'s door". Newspapers.com. The Miami Herald. p. A17. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Staples JE, Hills SL, Powers AM (26 August 2025). "CDC Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel: Chikungunya". Yellow Book. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 8 December 2025.

- ^ "Chikungunya". Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. 19 December 2024. Retrieved 10 December 2025.

- ^ "Priority pathogens". Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. 13 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2025.

- ^ CDC (2 December 2025). "Chikungunya Vaccine Information for Healthcare Providers". Chikungunya Virus. Retrieved 10 December 2025.

- ^ Maure C, Khazhidinov K, Kang H, Auzenbergs M, Moyersoen P, Abbas K, et al. (2 December 2024). "Chikungunya vaccine development, challenges, and pathway toward public health impact". Vaccine. 42 (26): 126483. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126483. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 39467413.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ Reddy A, Bosch I, Salcedo N, Herrera BB, de Puig H, Narváez CF, et al. (1 September 2020). "Development and Validation of a Rapid Lateral Flow E1/E2-Antigen Test and ELISA in Patients Infected with Emerging Asian Strain of Chikungunya Virus in the Americas". Viruses. 12 (9): 971. doi:10.3390/v12090971. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 7552019. PMID 32882998.

- ^ Kasabe B, Ahire G, Patil P, Punekar M, Davuluri KS, Kakade M, et al. (27 April 2023). "Drug repurposing approach against chikungunya virus: an in vitro and in silico study". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 13 1132538. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1132538. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 10174255. PMID 37180434.

- ^ Reis AC, de Oliveira CM, Rangel BC, de Carvalho LV, Portruneli C, Agostini Ld, et al. (2 July 2025). "Paulownin triazole-chloroquinoline derivative: a promising antiviral candidate against chikungunya virus". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 78 (7) ovaf092. doi:10.1093/lambio/ovaf092. ISSN 1472-765X. PMID 40608491.

- ^ "New research will help patients suffering debilitating after-effects of tropical viral infection". Keele University. 13 April 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2025.

- ^ Amaral JK, Bingham CO, Taylor PC, Vilá LM, Weinblatt ME, Schoen RT (1 March 2023). "Pathogenesis of chronic chikungunya arthritis: Resemblances and links with rheumatoid arthritis". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 52 102534. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102534. ISSN 1477-8939. PMID 36549417.

- ^ Padilla-Sanchez V (10 August 2025), Chikungunya Virus, doi:10.5281/zenodo.16790088, retrieved 10 August 2025

- ^ Rougeron V, Sam IC, Caron M, Nkoghe D, Leroy E, Roques P (1 March 2015). "Chikungunya, a paradigm of neglected tropical disease that emerged to be a new health global risk". Journal of Clinical Virology. 64: 144–52. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.08.032. ISSN 1386-6532. PMID 25453326.

- ^ a b Weaver SC, Osorio JE, Livengood JA, Chen R, Stinchcomb DT (September 2012). "Chikungunya virus and prospects for a vaccine". Expert Review of Vaccines. 11 (9): 1087–101. doi:10.1586/erv.12.84. PMC 3562718. PMID 23151166.

- ^ Powers AM, Brault AC, Shirako Y, Strauss EG, Kang W, Strauss JH, et al. (November 2001). "Evolutionary relationships and systematics of the alphaviruses". Journal of Virology. 75 (21): 10118–31. Bibcode:2001JVir...7510118P. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.21.10118-10131.2001. PMC 114586. PMID 11581380.

- ^ "NIAID Category A, B, and C Priority Pathogens". Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) Fifth Edition" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Powers AM, Brault AC, Tesh RB, Weaver SC (February 2000). "Re-emergence of Chikungunya and O'nyong-nyong viruses: evidence for distinct geographical lineages and distant evolutionary relationships". The Journal of General Virology. 81 (Pt 2): 471–79. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471 (inactive 11 July 2025). PMID 10644846.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Sahadeo NS, Allicock OM, De Salazar PM, Auguste AJ, Widen S, Olowokure B, et al. (2017). "Understanding the evolution and spread of chikungunya virus in the Americas using complete genome sequences". Virus Evol. 3 (1) vex010. doi:10.1093/ve/vex010. PMC 5413804. PMID 28480053.

- ^ a b Wang M, Wang L, Leng P, Guo J, Zhou H (1 March 2024). "Drugs targeting structural and nonstructural proteins of the chikungunya virus: A review". International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 262 (Pt 2) 129949. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129949. ISSN 0141-8130. PMID 38311132.

- ^ Voss JE, Vaney MC, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, et al. (December 2010). "Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography". Nature. 468 (7324): 709–12. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..709V. doi:10.1038/nature09555. PMID 21124458. S2CID 4412764.