Walaric

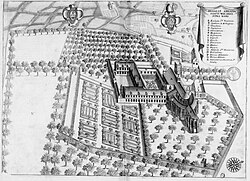

Saint Walaric,[a] modern French Valery (died 620), was a Frankish monk turned hermit who founded the Abbey of Saint-Valery-sur-Somme. His cult was recognized in Normandy and England.

Life

[edit]Saint Walaric was born in Auvergne to a peasant shepherd family.[1] As a young boy, Saint Walaric spent most of his childhood surrounded by nature, with old volcanic caves and circular crater lakes surrounding his homestead.[2] When Saint Walaric was a child he had an occupation of taking care and pasturing his sheep. Also as a child Saint Walaric had a desire to write and read, which was uncommon among his class in society,[3] but most importantly, he had a craving for learning. While his sheep would explore the grassy areas where he lived, he would spend most of his time teaching himself how to read and write. Growing up, Saint Walaric was described as being modest, sweet, gentle, and also known to be a fast learner. When not studying alone, Walaric took company with his uncle, who resided in a nearby monastery.[4]

Over the years, Walaric had jumped from a few monastic places such as the abbey of Autumo, abbey of Saint-Germain d'Auxerre, and finally the abbey of Luxeuil in Auxerre, France, where the idea of a saintly life became very appealing to him. When at the abbey of Luxeuil, Saint Walaric began to study under the Irish holy man Columbanus, who previously had been exiled by King Theuderic II’s grandmother Brunhild.[5] During the time of being with Columbanus, Walaric followed his teachings and Columbanus posed as a mentor for the saint. While being at the Columbanus' monastery, Saint Walaric practiced his horticulture skills by growing and preserving his vegetables and fruit, while also finding ways to exterminate the insects that would harm his crops.[6]

During his time in the abbey of Luxeuil, Saint Walaric met a man named Waldelenus. There is little information about this Waldelenus or his life. The only thing that is known about Waldelenus is that he was a prominent Luxovian monk. Waldelenus and Saint Walaric were responsible for creating the foundation of Leuconay, also known as Saint-Valéry. Waldelenus and Columbanus picked Saint Walaric to help with this foundation, as Saint Walaric was already an experienced, practicing monk and was around his fifties at the time of this foundation.[7] Saint Walaric’s monastery in Luxeuil fell under the Columbanian Rule, rather than the more common Benedictine Rule. Though the Columbanian Rule historically has been difficult to characterize, its presence greatly impacted politics and religion in the early times of Christianity in continental Europe.[8] Around the same time as the foundation of Leuconay, Walaric and Waldelenus preached in Neustira for a very short time. After a couple of years of preaching, Saint Walaric grew tired of preaching and decided to settle as a hermit near the mouth of the river Somme where a community began to rise around him.[9]

During the last days of Saint Walaric’s life, he spent most of his time on a little hill near Leuconany. This hill was where Walaric spent his time under a tree, musing and praying. Saint Walaric enjoyed the hill greatly, as he was able to see the dark blue sea and the white sands. The dark blue sea and the white sands spoke to him as the rocks and pines did. On a Sunday, Saint Walaric died, his body resting on a tree near the hill he loved during life.[10]

Valerian Prophecy

[edit]

Walaric makes an appearance in tenth century France at the transition of the Carolingian Dynasty in Western Francia to the Capetian Dynasty. After king Louis V died without an heir, the throne transitioned to Hugh Capet, the founder of the Capetian Dynasty, who received a vision where he was visited by Saint Walaric who legitimized Hugh Capet’s rule and thanked him for rescuing his remains from the Carolingians, who had been in serious decline across Europe with the collapse of both West Francia and East Francia.[11] He legitimized the Capetian Dynasty as a whole with the claim they would rule for seven generations, seven being a number commonly tied to eternity or perfection. The Capetians continued their reign until the fourteenth century with the last Capetian in France being Charles the IV in the fourteenth century.

England and Normandy

[edit]In the Eleventh century, the legacy of Saint Walaric is briefly written about by Orderic Vitalis (1075-1142 CE),[12] a monk of Saint-Evroul in Normandy. Vitalis, in his Historia Ecclesiastica, writes of how Saint Walaric is called upon when his remains, commonly referred to as relics, are used to pray for safe passage across the English channel in 1066 AD. This would lead to William the Conqueror starting his invasion of England, with the crossing of the English Channel being carried out and led by Duke William of Jumieges.[13] This led to Walaric being addressed as a patron saint of sailors, as the prayer led to a favorable wind across the channel, among Norman and French cultures as William’s invasion ultimately led to his victory and ascension to the English throne where Norman, French, and Anglo-Saxon cultures mixed together in a cultural exchange of language and customs. This spread of Walaric's cult included a chapel in Alnmouth dedicated to him and even a later transfer of relics from Saint-Valery-sur-Somme to Saint-Valery-en-Caux with a later transfer back to Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also spelled Walric, Waleric, Walericus, Walarich, Gualaric, etc.

References

[edit]- ^ Sesé, J. (28 February 2018). "David Hugh FARMER, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Oxford University Press, Oxford - New York 1987, XXVIII + 487 pp., 13 X 19,5". Scripta Theologica. 21 (1): 395. doi:10.15581/006.21.19003. ISSN 2254-6227.

- ^ Rainbow, Bernarr (2001), "Baring-Gould, Sabine", Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 7 November 2025

- ^ O'Hara, Alexander (16 April 2009). "The Vita Columbani in Merovingian Gaul". Early Medieval Europe. 17 (2): 126–153. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00257.x. ISSN 0963-9462.

- ^ Rainbow, Bernarr (2001), "Baring-Gould, Sabine", Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 7 November 2025

- ^ Palmer, James T. (22 November 2024). Merovingian Worlds. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65657-3.

- ^ Sesé, J. (28 February 2018). "David Hugh FARMER, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Oxford University Press, Oxford - New York 1987, XXVIII + 487 pp., 13 X 19,5". Scripta Theologica. 21 (1): 395. doi:10.15581/006.21.19003. ISSN 2254-6227.

- ^ Fox, Yaniv (18 September 2014). Power and Religion in Merovingian Gaul. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-58764-9.

- ^ Palmer, James T. (22 November 2024). Merovingian Worlds. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-65657-3.

- ^ Sesé, J. (28 February 2018). "David Hugh FARMER, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, Oxford University Press, Oxford - New York 1987, XXVIII + 487 pp., 13 X 19,5". Scripta Theologica. 21 (1): 395. doi:10.15581/006.21.19003. ISSN 2254-6227.

- ^ Rainbow, Bernarr (2001), "Baring-Gould, Sabine", Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 7 November 2025

- ^ Baldwin, John W. (31 December 1987). Government of Philip Augustus. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91111-6.

- ^ Roach, Daniel; Rozier, Charles C. (31 December 2016), "Introduction: Interpreting Orderic Vitalis", Orderic Vitalis: Life, Works and Interpretations, Boydell and Brewer, pp. 1–16, ISBN 978-1-78204-840-4, retrieved 7 November 2025

- ^ Orderic Vitalis (1 January 1969). "Oxford Medieval Texts: The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, Vol. 2: Books III and IV". The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780198222040.book.1.