Umayyad architecture

| Umayyad architecture | |

|---|---|

Top: Dome of the Rock (688–692); Middle: Great Mosque of Damascus (705–715); Bottom: Hisham’s Palace (Khirbat al-Mafjar) (8th century) | |

| Years active | 661–750 CE |

Umayyad architecture developed in the Umayyad Caliphate between 661 and 750, primarily in its heartlands in historical Syria.[a] It drew extensively on the architecture of older Middle Eastern and Mediterranean civilizations including the Sassanian Empire and especially the Byzantine Empire, but introduced innovations in decoration and form.[1][2] Under Umayyad patronage, Islamic architecture began to mature and acquire traditions of its own, such as the introduction of mihrabs to mosques, a trend towards aniconism in decoration, and a greater sense of scale and monumentality compared to previous Islamic buildings.[1][3][4] The most important examples of Umayyad architecture are concentrated in the capital of Damascus and the Greater Syria region, including the Dome of the Rock, the Great Mosque of Damascus, and secular buildings such as the Al-Mushatta Palace, Qusayr 'Amra, Hisham's palace (Khirbat Al-Mafjar), Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi and the ruins of Anjar.[1][2][5]

Historical background

[edit]

The Umayyad Caliphate was established in 661 after Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammad, was murdered in Kufa. Muawiyah I, governor of Syria, became the first Umayyad caliph.[6] The Umayyads made Damascus their capital.[7] Under the Umayyads the Arab empire continued to expand, eventually extending to Central Asia and the borders of India in the east, Yemen in the south, the Atlantic coast of what is now Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula in the west.[8] The Umayyads built new cities, often unfortified military camps that provided bases for further conquests. Wasit in present-day Iraq was the most important of these, and included a square Friday mosque with a hypostyle roof.[8]

The empire was tolerant of existing customs in the conquered lands, creating resentment among those looking for a more theocratic state. In 747, a revolution began in Khorasan, in the east.[8] By 750 the Umayyads had been overthrown by the Abbasids, who moved the capital to Mesopotamia. A branch of the Umayyad dynasty continued to rule in Iberia until 1051.[8]

During the 10 years of Al-Walid I rule (r. 705–715), a great number of institutions have been built or expanded, including the expansions of Prophet's Mosque in Medina, which saw the introduction of the first mihrab,[9] and the building of the Great Mosque of Damascus (the oldest mosque still in use in its original form).[10] These mosques became large enough to serve as congregational mosques for Friday prayers.[11] He also renovated the Great Mosque of Sanaa,[11] most likely built the settlement of Anjar,[12][13] and completed the construction of Al-Aqsa Mosque (Qibli Mosque) that had been started by his predecessor and father Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705) who also built the Dome of Rock (both part of Al-Aqsa compound),[14] The two caliphs are also credited with renovating the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca.[15] The original Great Mosque of Aleppo was completed by his successor and brother Sulayman (r. 715–717).[16]

Characteristics

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

The Umayyads adopted the construction techniques of Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture.[17] The reuse of elements from classical Roman and Byzantine art was particularly evident because political power and patronage was centered in Syria, formerly part of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire.[1] Almost all monuments from the Umayyad period that have survived are in Syria and Palestine.[8] They also often re-used existing buildings. There was some innovation in decoration and in types of building.[8] A significant amount of experimentation occurred as Umayyad patrons recruited craftsmen from across the empire and architects were allowed, or even encouraged, to mix elements from different artistic traditions and to disregard traditional conventions and restraints.[1]

Most buildings in Syria were of high quality ashlar masonry, using large tightly-joined blocks, sometimes with carving on the facade. Stone barrel vaults were only used to roof small spans. Wooden roofs were used for larger spans, with the wood in Syria brought from the forests of Lebanon. These roofs usually had shallow pitches and rested on wooden trusses. Wooden domes were constructed for Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, both in Jerusalem.[5] Baked brick and mud brick were used in Mesopotamia, due to lack of stone. Where brick was used in Syria, the work was in the finer Mesopotamian style rather than the more crude Byzantine style.[5]

Umayyad architecture is distinguished by the extent and variety of decoration, including mosaics, wall painting, sculpture and carved reliefs with Islamic motifs.[5] The Umayyads used local workers and architects. Some of their buildings cannot be distinguished from those of the previous regime. However, in many cases eastern and western elements were combined to give a distinctive new Islamic style. For example, the walls at Qasr Al-Mushatta are built from cut stone in the Syrian manner, the vaults are Mesopotamian in design and Coptic and Byzantine elements appear in the decorative carving.[5] While figural scenes were notably present in monuments like Qusayr 'Amra, non-figural decoration and more abstract scenes became highly favoured, especially in religious architecture.[19][1] The horseshoe arch appears for the first time in Umayyad architecture, later to evolve to its most advanced form in al-Andalus.[20]

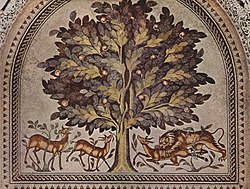

The Umayyad period represents the high point of mosaic art in Islamic architecture. Mosaics, composed of glass tesserae, were used to decorate the mosques of Al-Aqsa, Damascus, Medina, Mecca, Aleppo, and possibly Fustat. Added together, these mosaics would cover around 22,000 square metres (240,000 sq ft).[21] The most important examples are the mosaics in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and the Dome of Rock in Jerusalem, which survive to this day.[22] Those in Damascus feature depictions of trees and palaces in a late antique style, while the mosaics in Medina (no longer extant) were reported to contain similar images.[21]

Dome of the Rock

[edit]

The sanctuary of the Dome of the Rock, standing in the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound in Jerusalem, is the oldest surviving major Islamic building.[8][23] It is also an exceptional monument within the context of Umayyad and wider Islamic architecture, in terms of both its form and function.[2] It was not a mosque but rather a shrine or commemorative monument, likely built to honour ancient religious associations with the site such as the creation of Adam and Abraham's sacrifice. It acquired further layers of meaning over time and became most commonly associated with the "Night Journey" of Muhammad. It was also built as a visual symbol of Islamic dominance and its high dome was likely designed to compete for prominence with the dome of the nearby Christian Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[2][23]

The building followed the design of a Byzantine martyrium.[2][23] It consists of an octagonal structure, inside of which is another octagon formed by piers and columns, and finally an inner circular ring of piers and columns at the center.[23] Although the exterior of the building is now covered in 16th-century Ottoman tiles, both the exterior and interior were originally decorated with lavish mosaics, with the interior mosaics still mostly preserved today.[2][23] The mosaics are entirely aniconic, a characteristic that would continue in later Islamic decoration.[2] The imagery consists of vegetal motifs and other objects such as vases and chalices.[23] The building was also decorated with long inscriptions containing Qur'anic inscriptions chosen to emphasize the superiority of Islam over the preceding Abrahamic religions.[23]

Mosques

[edit]General development

[edit]The earliest mosques were often makeshift. In Iraq, they evolved from square prayer enclosures.[8] The ruins of two large Umayyad mosques have been found in Samarra, Iraq. One is 240 by 156 feet (73 by 48 m) and the other 213 by 135 metres (699 by 443 ft). Both had hypostyle designs, with roofs supported by elaborately designed columns.[24]

In Syria, the Umayyads preserved the overall concept of a court surrounded by porticos, with a deeper sanctuary, that had been developed in Medina. Rather than make the sanctuary a hypostyle hall, as was done in Iraq, they divided it into three aisles. This may have been derived from church architecture, although all the aisles were the same width.[3] In Syria, churches were converted to mosques by blocking up the west door and making entrances in the north wall. The direction of prayer was south towards Mecca, so the long axis of the building was at right angles to the direction of prayer.[25]

The Umayyads introduced a transept that divided the prayer room along its shorter axis.[3] They also added the mihrab to mosque design.[3] The Prophet's Mosque in Medina built by al-Walid I had the first mihrab, a niche on the qibla wall, which seems to have represented the place where the Prophet stood when leading prayer. This almost immediately became a standard feature of all mosques.[3] The minbar also began appearing in mosques in cities or administrative centers, a throne-like structure with regal rather than religious connotations.[3]

Great Mosque of Damascus

[edit]

The Great Mosque of Damascus was built by the caliph al-Walid I around 706–715.[7] Some scholars have argued that the first Umayyad version of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, begun by Abd al-Malik (al-Walid's father) and now replaced by later constructions, had a layout very similar to the current Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and that it probably served as a model for the latter.[26][27] The layout remains largely unchanged and some of the decoration has been preserved. The Great Mosque was built within the area of a Roman temenos from the first century.[7] The exterior walls of the earlier building, once a temple of Jupiter and later a church, were retained, although the southern entrances were walled up and new entrances made in the north wall. The interior was completely rebuilt.[28]

The Damascus mosque is rectangular, 157.5 by 100 metres (517 by 328 ft), with a covered area 136 by 37 metres (446 by 121 ft) and a courtyard 122.5 by 50 metres (402 by 164 ft) surrounded by a portico.[7] The prayer hall has three aisles parallel to the qibla wall, a common arrangement in Umayyad mosques in Syria.[7] The court holds a small octagonal building on columns. This was the treasury of the Muslims, perhaps only symbolic, which was traditionally kept in a town's main mosque.[29] The mosque was richly decorated with mosaics and marble. A rich composition of marble paneling covered the lower walls, though only minor examples of the original marbles have survived today near the east gate.[30] The marble window grilles in the great mosque, which diffuse the light, are worked in patterns of interlocking circles and squares, precursors to the arabesque style that would become characteristic of Islamic decoration.[31]

Vast portions of the mosque's walls were decorated with mosaics, of which some original fragments have survived, including some that depict the houses, palaces and river valley of Damascus.[28] Byzantine artisans were reportedly employed to create them, and their imagery reflects a late Roman style.[33][34][35] They reflected a wide variety of artistic styles used by mosaicists and painters since the 1st century CE, but the combined use of all these different styles in the same place was innovative at the time.[36] Similar to the Dome of the Rock, built earlier by Abd al-Malik, vegetation and plants were the most common motif, but those of the Damascus mosque are more naturalistic.[36] In addition to the large landscape depictions, a mosaic frieze with an intricate vine motif (referred to as the karma in Arabic historical sources) once ran around the walls of the prayer hall, above the level of the mihrab.[37] The only notable omission is the absence of human and animal figures, which was likely a new restriction imposed by the Muslim patron.[36] Scholars have long debated the meaning of the mosaic imagery. Some historical Muslim writers and some modern scholars have interpreted them as a representation of all the cities in the known world (or within the Umayyad Caliphate at the time), while other scholars interpret them as a depiction of Paradise.[36]

Other mosques

[edit]The Great Mosque of Damascus served as a model for later mosques.[8] Similar layouts, scaled down, have been found in a mosque excavated in Tiberias, on the Sea of Galillee, and in a mosque in the palace of Khirbat al-Minya.[7] The plan of the White Mosque at Ramla differs in shape, and the prayer hall is divided into only two aisles.[b] This may be explained by construction of underground cisterns in the Abbasid period, causing the original structure to be narrowed.[27]

When the caliphs Abd al-Malik and al-Walid I renovated the Great Mosque of Mecca, a work that likely went on for many years, they built a covered area inside the mosque likely consisting of a portico with a roof. They reportedly added embellishments such as marble, mosaics on the soffits or spandrels, crenelations on the walls, and gilding on the upper columns or their capitals.[15]

The Great Mosque of Hama was founded in the Umayyad period when a church, originally a Roman temple, was converted into a mosque.[40] The dating of its oldest elements, however, has been a subject of controversy: Jean Sauvaget argued that the riwaqs (arcades) in its courtyard dated from the Umayyad period, while K. A. C. Creswell cast doubt on this dating. The historic mosque was completely destroyed in 1982.[40] The original foundation of the Great Mosque of Aleppo is also attributed to the Umayyad period, but the current building contains no visible traces of this period, except perhaps in its overall floor plan with a hypostyle hall and courtyard.[41][42][1]

Other mosques attributed to the Umayyads, whether extant or non-extant, include the Umayyad Mosque of Baalbek,[43] a mosque in Jerash (ruined),[43] a mosque in the Citadel of Amman (ruined),[44] and the Umayyad Mosque of Mosul (demolished).[45][46] The al-Omari Mosque in Bosra, founded by the earlier Rashidun caliph Umar, was also completed by the Umayyad caliph Yazid II, though it was later renovated during the Ayyubid period (12th-13th centuries).[47][better source needed]

Palaces and settlements

[edit]Desert castles

[edit]

The Umayyads are known for their so-called "desert palaces" or "desert castles": elite residences located around the edges of the Syrian Desert, mostly in present-day Jordan and Syria.[52][53] Most of them were abandoned after the Umayyads fell from power and remain as ruins.[5] 38 examples of these have been discovered so far and have provided modern scholars with important evidence about Umayyad material culture and court life.[53]

Some were new constructions and some were adapted from earlier Roman or Byzantine forts.[5] Some were small and limited in scope while others, like Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi, were fortified settlements. The palaces were symbolically defended by walls, towers and gates. In some cases the outside walls carried decorative friezes.[5] The palaces would have a bathhouse, a mosque, and a main castle. The entrance to the castle would usually be elaborate. Towers along the walls would often hold apartments with three or five rooms.[54] These rooms were simple, indicating they were little more than places to sleep.[5] The palaces often had a second floor holding formal meeting rooms and official apartments.[54]

The fortress-like appearance was misleading. Thus Qasr Kharana appears to have arrowslits, but these were purely decorative.[55] The fortress-like plan was derived from Roman forts built in Syria, and construction mostly followed earlier Syrian methods with some Byzantine and Mesopotamian elements. The baths derive from Roman models, but had smaller heated rooms and larger ornate rooms that would presumably have been used for entertainment.[54] The palaces had floor mosaics and frescoes or paintings on the walls, with designs that show both eastern and western influences. One fresco in the bath of Qusayr 'Amra depicts six kings. Inscriptions below in Arabic and Greek identify the first four as the rulers of Byzantium, Spain (at that time Visigothic), Persia and Abyssinia.[56] Stucco sculptures were sometimes incorporated in the palace buildings.[57]

Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi is about 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Palmyra on the main road from Aleppo to Iraq. A large walled enclosure 7 by 4 kilometres (4.3 by 2.5 mi) was presumably used to contain domestic animals.[58] A walled madina, or city, contained a mosque, an olive oil press and six large houses. Nearby there was a bath and some simpler houses. According to an inscription dated 728, the caliph provided significant funding for its development.[58] The settlement has a late antique Mediterranean design, but was soon modified. The madina originally had four gates, one in each wall, but three were soon walled up. The basic layout was formal, but the buildings often failed to comply with the plan.[58]

-

Qusayr 'Amra desert castle in Jordan, first half of 8th century[59]

-

Fresco paintings in Qusayr 'Amra, Jordan

-

Reconstructed Mosque in Qasr al-Hallabat, in Jordan, a former Roman fort[60] converted to an Umayyad residence in the 8th century[61]

-

Central vault of the Hammam as-Sarah bathhouse, part of Qasr Al-Hallabat, in Jordan

-

Mosaic inside Hammam as-Sarah

-

Courtyard inside the Qasr Kharana

-

Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi in Syria, dated to 728[58]

-

Entrance of Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi

-

Ruins of Khirbat al-Minya in Galilee, 8th century[61]

-

Decoration from Khirbat al-Minya

-

Part of the facade of Qasr Al-Mushatta now held in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

-

Entrance of Hisham's Palace (Khirbat al-Mafjar) near Jericho, Palestine, attributed to al-Walid II (r. 743–744)[64]

-

Sculpted stonework inside Hisham's Palace

Anjar

[edit]The archeological site of Anjar, located in the Beqaa Valley in present-day Lebanon, is notable for preserving the remains of an Umayyad-era settlement. It was constructed by the caliph al-Walid I, with a graffiti inscription in the quarries of Kamid suggesting a construction date of 714–715 CE (96 AH).[12][13][65] It is unclear whether an earlier settlement existed on the site.[66][13][67]

The settlement was built within a rectangular enclosure, measuring 370 by 310 metres (1,210 by 1,020 ft), delineated by a perimeter wall built in stone. The wall was marked by semi-circular buttress towers at regular intervals and pierced by four main gates oriented towards the four cardinal directions. The four gates were connected by two straight colonnaded avenues lined with shops, which crossed in the center of the settlement under a tetrapylon.[68][69] Today, the enclosure contains the remains of several palaces, a mosque, two bathhouses, and a well. Many of the structures are built of alternating courses of stone and brick, a technique shared with Byzantine architecture.[68][69] Many types of decoration have been found at the site featuring vegetal, geometric, and figural motifs.[68][70] One of the bathhouses features a mosaic floor.[68]

-

Anjar, Lebanon, built in the 8th century, with view of colonnaded street

-

General view of the ruins

-

Detail of arches and columns of a palace

-

Remains of stone decoration

Amman Citadel

[edit]

The Citadel of Amman, located on a high hill in present-day downtown Amman, contains the remains of an Umayyad palace complex, built c. 735 to serve as the local governor's residence.[71] The most significantly preserved element is a reception hall or audience hall at the entrance to the palace, built over the foundations of an earlier Roman/Byzantine building. It has a square floor plan, with a central cruciform space of four iwans, with smaller square rooms occupying the four corners.[72] The central space is covered today by a dome, although this is a modern reconstruction[73] and it is possible that the original structure was not domed.[74][75][76][77] The walls are decorated with rows of blind niches featuring ornamental rosettes and palmettes. This decoration, along with the arrangement of four iwans, suggest the influence of Iranian architecture, particularly of Sasanian structures in present-day Iraq and possibly the work of craftsmen from this region.[78][71][77] Behind this reception hall was a square courtyard and a colonnaded street, flanked by apartments on either side, which led to another courtyard, an iwan, and finally another domed cruciform hall that may have been a throne hall.[77][79]

South of the palace, across from the reception hall, are the remains of a mosque. Like other Umayyad mosques, it has a hypostyle prayer hall and central peristyle courtyard. Its northern façade was marked by a series of buttresses and decorative niches.[80] East of the reception hall are the remains of a bathhouse as well as a large circular water reservoir or cistern, which is 16 metres (52 ft) in diameter and 5 metres (16 ft) deep. The reservoir drew water from other parts of the hill via two drains, one of which has a shaft that may have helped to filter the water.[78]

-

Floor plan of the cruciform reception hall

-

Interior of the reception hall

-

Remains of the colonnaded street in the palace

-

Remains of the citadel's mosque (foreground)

-

The Umayyad cistern

Notable examples

[edit]Jordan

[edit]- Qusayr 'Amra

- Qasr al-Hallabat

- Umayyad Palace at the Amman Citadel

- Hammam as-Sarah

- Qasr al-Qastal

- Qasr Kharana

- Qasr Al-Mushatta

- Qasr Tuba

- Qasr al-Muwaqqar

Lebanon

[edit]Palestine

[edit]Syria

[edit]Israel

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The architecture of the later Umayyad state in the Iberian Peninsula (between 756 and 1031) is covered at Moorish architecture.

- ^ Other than the traces of its floor plan, almost nothing of the White Mosque's original Umayyad construction has survived to the present day.[38][39]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture (III. 661–c. 750)". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 62–78. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tabbaa, Yasser (2007). "Architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ a b c d e f Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Mihrab". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 515. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Petersen 1996, p. 296.

- ^ Hawting 2002, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f Cytryn-Silverman 2009, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Petersen 1996, p. 295.

- ^ Ali 1999, p. 33.

- ^ Kuban 1974, p. 14.

- ^ a b Mawani, Rizwan (2019). Beyond the Mosque: Diverse Spaces of Muslim Worship. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-78673-662-8.

- ^ a b Chehab 1993, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Hillenbrand 1999, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Ragab, Ahmed (2015). The Medieval Islamic Hospital: Medicine, Religion, and Charity. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-107-10960-5.

- ^ a b Grabar, Oleg (1985). "Upon Reading al-Azraqi". Muqarnas. 3: 64–66. doi:10.2307/1523080. ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ Kuban 1974, p. 16.

- ^ Talgam 2004, pp. 48ff.

- ^ Whitcomb & Ṭāhā 2013, p. 58.

- ^ Petersen 1996, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Ali 1999, p. 35.

- ^ a b Leal 2020, p. 29.

- ^ Leal 2020, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Jerusalem". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 347. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Aldosari 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 295-296.

- ^ Grafman & Rosen-Ayalon 1999, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Cytryn-Silverman 2009, p. 51.

- ^ a b Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 705.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Ali 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 102.

- ^ Rosenwein 2014, p. 56.

- ^ Kleiner 2013, p. 264.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Damascus". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 513. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Flood 1997.

- ^ Murphy-O'Connor 2008, p. 447.

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 245.

- ^ a b O'Kane, Bernard (2009). "The Great Mosque of Hama Redux". Creswell Photographs Re-examined: New Perspectives on Islamic Architecture. American University in Cairo Press. pp. 219–246. ISBN 978-977-416-244-2.

- ^ Tabbaa, Yasser (2011). "Aleppo, architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

The Great Mosque, founded by the Umayyad caliph al-Walīd I (r. 86–96/705–15) and probably completed by Sulaymān (r. 96–9/715–7), on the grounds of the Byzantine cathedral, stands at the heart of Aleppo. Unlike the Great Mosque of Damascus, the Great Mosque of Aleppo shows little of its original Umayyad form, which does not seem to have left any visible remains beyond its spacious hypostyle layout, since it burnt down and was totally rebuilt in the sixth/twelfth century and later.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 40.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-297-86559-9.

- ^ Hawting 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Francis, Bashir Youssef. موسوعة المدن والمواقع في العراق - الجزء الأول [Encyclopedia of cities and sites in Iraq (Volume 1)] (in Arabic). E-Kutub Ltd. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-78058-262-7.

- ^ Nováček, Karel; Melčák, Miroslav; Beránek, Ondřej; Starková, Lenka (2021). Mosul after Islamic State: The Quest for Lost Architectural Heritage. Springer Nature. p. 289. ISBN 978-3-030-62636-5.

- ^ Fairbairn, Donald (2021). The Global Church---The First Eight Centuries: From Pentecost through the Rise of Islam. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0-310-09786-0.

- ^ Williams, Betsy (12 April 2012). "Qusayr 'Amra". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2025-10-31.

- ^ Drayson 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Fowden 2004, p. 205.

- ^ Genequand 2020, p. 246.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Palace". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Genequand 2020, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 39.

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 706-707.

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Qusayr 'Amra". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Petersen 1996, p. 138.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture; X. Decoration; D. Mosaics". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Grabar & Jenkins-Madina 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Mshatta". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Khirbat al-Mafjar". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 383. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Santi 2018, p. 270.

- ^ Chehab 1993.

- ^ Santi 2018.

- ^ a b c d Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Anjar". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Petersen 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Santi 2018, p. 268.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Amman". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Bisheh et al. 2010, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Tabbaa, Yasser (2010). Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo. Penn State University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-271-04331-9.

- ^ Almagro & Olavarri 1982, p. 310.

- ^ Almagro 1994, p. 423.

- ^ Northedge, Alastair; Bennett, Crystal-M. (1992). Studies on Roman and Islamic ʻAmmān: History, site and architecture. British Institute in Amman for Archaeology and History. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-727002-8.

- ^ a b c Petersen 1996, p. 18.

- ^ a b Bisheh et al. 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Bisheh et al. 2010, p. 66-67.

- ^ Bisheh et al. 2010, p. 65.

Sources

[edit]- Aldosari, Ali (2006). Middle East, western Asia, and northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Ali, Wijdan (1999). The Arab Contribution to Islamic Art: From the Seventh to the Fifteenth Centuries. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-424-476-6. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Almagro, Antonio; Olavarri, Emilio (1982). "A New Umayyad Palace at the Citadel of Amman". Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan. 1: 305–321.

- Almagro, Antonio (1994). "A Byzantine Building with a Cruciform Plan in the Citadel of Amman" (PDF). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. 38: 417–427.

- Bisheh, Ghazi; Zayadine, Fawzi; al-Asad, Mohammad; Kehrberg, Ina; Tohme, Lara (2010) [2000]. The Umayyads: The Rise of Islamic Art (2nd ed.). Ministry of Tourism, Department of Antiquities & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-1-874044-35-2.

- Burns, Ross (2009) [1992]. The Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845119478.

- Chehab, Hafez K. (1993). "On the Identification of ?Anjar (?Ayn al-Jarr) as an Umayyad Foundation". Muqarnas. 10: 42–48. doi:10.2307/1523170. ISSN 0732-2992.

- Cytryn-Silverman, Katia (2009-10-31). "The Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias". Muqarnas. BRILL. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Enderlein, Volkmar (2011). "Syria and Palestine: The Umayyad Caliphate". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. H. F. Ullmann. pp. 58–87. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Drayson, Elizabeth (2006). "Ways of Seeing: The First Medieval Islamic and Christian Depictions of Roderick, Last Visigothic King of Spain". Al-Masaq. 18 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1080/09503110600863443. ISSN 0950-3110. S2CID 161084788.

- Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088670.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (1997). "Umayyad Survivals and Mamluk Revivals: Qalawunid Architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus". Muqarnas. 14. Boston: Brill: 57–79. doi:10.2307/1523236. JSTOR 1523236.

- Fowden, Garth (2004). Qusayr 'Amra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92960-9.

- Genequand, Denis (2020). "Elites in the countryside: The economic and political factors behind the Umayyad 'desert castles'". In Marsham, Andrew (ed.). The Umayyad World. Routledge. pp. 240–266. ISBN 978-1-317-43005-6.

- Grafman, Rafi; Rosen-Ayalon, Myriam (1999). "The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus". Muqarnas. 16. Boston: Brill: 1–15. doi:10.2307/1523262. JSTOR 1523262.

- Hawting, G. R (2002-01-04). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-203-13700-0. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Hillenbrand, Robert (1999). "Anjar and Early Islamic Urbanism". In Brogiolo, G. P.; Ward-Perkins, B. (eds.). The Idea and Ideal of the Town Between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Brill. pp. 59–98.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29138-5. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Kleiner, Fred (2013). Gardner's Art through the Ages, Vol. I. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781111786441.

- Kuban, Doğan (1974). The Mosque and its Early Development. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-03813-4.

- Leal, Bea (2020). "The Abbasid Mosaic Tradition and the Great Mosque of Damascus". Muqarnas. 37: 29–62. ISSN 0732-2992.

- Murphy-O'Connor, Jerome (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199236664.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2014). A Short History of the Middle Ages. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442606142.

- Santi, Aila (2018). "ʿAnjar in the shadow of the church? New insights on an Umayyad urban experiment in the Biqāʿ Valley". Levant. 50 (2): 267–280.

- Talgam, Rina (2004). The Stylistic Origins of Umayyad Sculpture and Architectural Decoration. Vol. 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04738-8. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- Whitcomb, Donald; Ṭāhā, Ḥamdān (2013). "Khirbat al-Mafjar and Its Place in the Archaeological Heritage of Palestine". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 1 (1): 54–65. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.1.1.0054. JSTOR 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.1.1.0054.

![Qusayr 'Amra desert castle in Jordan, first half of 8th century[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Qasr_Amra_1.jpg/120px-Qasr_Amra_1.jpg)

![Reconstructed Mosque in Qasr al-Hallabat, in Jordan, a former Roman fort[60] converted to an Umayyad residence in the 8th century[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Qasr_Al-Hallabat_mosque.jpg/120px-Qasr_Al-Hallabat_mosque.jpg)

![Qasr Kharana in Jordan, dated to c. 710[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Qasr_Kharana_in_Jordan.jpg/120px-Qasr_Kharana_in_Jordan.jpg)

![Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi in Syria, dated to 728[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Qasr_al-Hayr_al-Sharqi%2C_Walls_and_towers%2C_Syria.jpg/120px-Qasr_al-Hayr_al-Sharqi%2C_Walls_and_towers%2C_Syria.jpg)

![Ruins of Khirbat al-Minya in Galilee, 8th century[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Minya.jpg/120px-Minya.jpg)

![Qasr al-Mushatta in Jordan, possibly built by al-Walid II (r. 743–744)[63]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Qasr_al-Mushatta.jpg/120px-Qasr_al-Mushatta.jpg)

![Entrance of Hisham's Palace (Khirbat al-Mafjar) near Jericho, Palestine, attributed to al-Walid II (r. 743–744)[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Hisham_Palace_in_Jericho2.jpg/120px-Hisham_Palace_in_Jericho2.jpg)