Thierry Ardisson

Thierry Ardisson | |

|---|---|

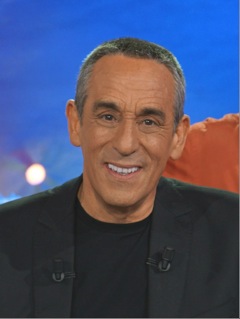

Ardisson in 2014 | |

| Born | 6 January 1949 Bourganeuf, Creuse, France |

| Died | 14 July 2025 (aged 76) Paris, France |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse(s) | Béatrice Ardisson (1988-2010)[1] Audrey Crespo-Mara (m. 2014) |

| Website | thierryardisson |

Thierry Ardisson (6 January 1949 – 14 July 2025) was a French television producer and host. He was also a film producer, writer, and advertising executive.

He began his career in advertising by founding the agency Business, then moved into print media. He made his television debut in the late 1980s with shows such as Bains de minuit and Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches. After a brief withdrawal in the early 1990s, the man nicknamed “the man in black” returned with several successful programs.

Some of his television programs are considered among the most influential and have some of the longest run times in French television, notably Paris Dernière,Tout le monde en parle, On a tout essayé (as producer),[2] and Salut les Terriens!, later renamed Les Terriens du samedi!.

He was the author of several books, including best-sellers such as Louis XX – Contre-enquête sur la Monarchie and Confessions d’un Baby boomer.[3] In 2013, he released and produced the French movie Max.[4][5]

Ardisson was a Legitimist French Royalist [6] and a friend of Louis Alphonse de Bourbon (Louis XX), the current Legitimist claimant to the French throne.

Early life

[edit]Thierry Ardisson was born on January 6, 1949, in Bourganeuf, in the Creuse department, where his family had temporarily relocated for a construction project.[7] He spent part of his early childhood in Algeria, where his father worked on restoring the Mers El Kébir military base. He has a younger brother, Patrick.

Thierry’s parents are originally from the Nice region in southern France. His mother, Juliette Renée Gastinel (1930–2022), was a homemaker, and his father, Victor Ardisson (1925–2004), was a civil engineer working in the construction sector, notably for the company founded by André Borie, which required the family to move frequently.

In 1957, the family moved to Arêches in the Beaufortain area of Savoie, as his father was assigned to the construction of the Roselend Dam, one of France’s largest. Ardisson attended Collège Saint-Michel (Annecy) and later earned a degree in English from the University of Montpellier Paul Valéry.

At age 17, while working as a DJ at the Whisky à Gogo nightclub in Juan-les-Pins, Ardisson had a first homosexual experience, which he details in his autobiography Confessions d'un baby-boomer.[8]

Career

[edit]Early career in advertising and journalism

[edit]Thierry Ardisson began his career as a copywriter in advertising. In 1969, he moved to Paris and was hired in the sales promotion department at BBDO, then at TBWA, and later at Ted Bates, before co-founding his own agency, Business, in 1978 with Éric Bousquet and Henri Baché.[9]

While working at Business, Ardisson invented the 8-second TV ad format, enabling advertisers with limited budgets to access TV advertising.[10]

As a copywriter, he is also credited with creating several memorable advertising slogans for French consumers:

- "Ovomaltine, c'est de la dynamique!"[11][12][13]

- "Vas-y Wasa!"[12]

- "Lapeyre, y en a pas deux!"[12]

- "Chaussée aux Moines:[14]

- "Quand c’est trop, c’est Tropico!"[15]

These slogans foreshadowed gimmicks used in his later television shows, such as Magnéto, Serge! (addressed to Serge Khalfon) and Qu'est-ce qu'on écoute, Corti? (about DJ Philippe Corti).

The Business agency also supplied "turnkey" articles to the French press, including the series L’Hebdo des Savanes and Descentes de Police.

In the mid-1970s, Ardisson contributed to the underground magazine, Façade[9] alongside Alain Benoist, Jean-Luc Maître, and Laurent Laclos. During this period, he is a regular at Le Palace nightclub.

In 1984, Ardisson was hired as the vice-director of publications for the Hachette-Filipacchi press group. He subsequently took over the magazine L’Écho des savanes, which he temporarily renamed L’Hebdo des Savanes. The topics covered, considered too provocative, led to his discharge.[9]

But in 1992, he worked a new partnership with Hachette-Filipacchi and launched the magazine Interview.[1] A year later, after losing a plagiarism lawsuit brought by the American magazine Interview, he was forced to rename it Entrevue. He eventually sold his shares of the company back to Hachette-Filipacchi in 1995.[16]

In 1998, together with Francis Morel, Alexis Kebbas and the Springer editions, Ardisson launched the consumer magazine J’économise (“I save up”) which peaked at 420,000 prints.[17]

Career in television

[edit]1980s

[edit]In 1980, in the course of the interviews that his agency Business conducted for French newspapers and magazines, Ardisson interviewed French tennis player Yannick Noah who admitted to smoking hashish and that tennis players regularly took amphetamines before the games, a scandal that led to his first appearance on television.[18]

In 1985, at the suggestion of producer Marie-France Brière,[19] Ardisson adapted his press interviews (called Descente de police) for the French TV network TF1,[20] a program in which guest personalities were subjected to a harsh and abrupt police-style interrogation. The concept – too brutal and provocative – got censored by French media authorities and the show taken off the air a few months later. With the support of Hervé Bourges, who had given him carte blanche, he nevertheless remained at TF1 and hosted Scoop à la une.[21]

From 1986 to 1987, he co-produced À la folie pas du tout with Catherine Barma, hosted by Patrick Poivre d’Arvor.[22] In 1987, Thierry Ardisson sold his shares in his advertising agency Business and founded the TV production company Ardisson & Lumières.

From September 1987 to June 1988, together with Catherine Barma, he created and served as artistic director for the show Face à France on La Cinq TV network, hosted by Guillaume Durand; Bains de minuit, a so-called trendy late-night show which he presented from the nightclub Les Bains Douches;[23] and Childéric, a hit parade show hosted by Childéric Muller. On 9 September 1988, alongside DJ Claude Challe, co-owner of Les Bains Douches, he presented on Antenne 2 the Prince concert in Dortmund, Germany.

From 1988 to 1990, he hosted Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches from the Palace, a famous nightclub, on Antenne 2 in late-night Saturday slot.[24] The program, intended as a rock show, replaced Les Enfants du rock, which had just ended. The show’s title was taken from an advertising slogan he had coined for Glamor sunglasses ten years earlier. For this program, he devised the concept of “formatted interviews” such as Interview première fois, Auto-interview, and Questions cons. The show was later parodied on La télé des Inconnus, notably with Didier Bourdon imitating Ardisson, Bernard Campan parodying Laurent Baffie, and Pascal Légitimus parodying the host Arthur. Much later, Guillaume Durand described Ardisson as “one of the greatest interviewers of the past thirty years: his very long shoots produced daring, risky interviews.”[25] In parallel, still working with Catherine Barma, he co-produced Stars à la barre[26] for Antenne 2, initially hosted by Roger Zabel and later by Daniel Bilalian.

Afterwards, Ardisson took over the Saturday 7 p.m. slot with Télé Zèbre, featuring Yves Mourousi, Françoise Hardy, Philippe Manœuvre and two newcomers, Yvan Le Bolloc'h and Bruno Solo.[27][28]

1990s

[edit]In June 1990, he hosted a documentary, Rolling Stones: The Impossible Twins, on Antenne 2.

From 1991 to 1992, he presented Double Jeu on Antenne 2 in late night, featuring hidden-camera sketches by Laurent Baffie, Philippe Guérin’s quiz “Info or Intox,” and Philippe Corti’s music blind test. Considered too provocative, the program was canceled by France 2 management in early January 1993.[29] A month later, he returned on France 2 with Ardimat, a show in which the host threatened to kill his dog if ratings fell. The program lasted ten episodes before being taken off the air as well.

From 1992 to 1994, he produced Frou-Frou[30], hosted by Christine Bravo and also attempted, unsuccessfully, to launch a print magazine of the same name. He also produced the shows Graines de Stars[31] and Flashback.

In January 1993, he presented Cœur d'Ardishow on France 2, a retrospective of his previous programs. In 1994, after the failure of Ardimat and Autant en emporte le temps, he stepped back from hosting but remained a producer, notably of Graines de star and FlashBack on M6 with Laurent Boyer.[32]

In 1995, he produced the Fringe time for TF1, Les Niouzes, with Laurent Ruquier. Following poor ratings, he requested that the program be taken off the air after its first week.[33] That same year, he produced and hosted Paris Dernière on the French cable channel Paris Première.[34]

From 1995 to 1998, he produced Top Flop for Paris Première, hosted by Alexandra Kazan.

Starting in 1997, he hosted Rive droite / Rive gauche with Frédéric Beigbeder, Élisabeth Quin and Philippe Tesson,[35] regaining success after several years of setbacks and failures.[25] In partnership with the Lagardère group and Sony Television, he also created Free One, a planned 24/7 live TV channel intended for distribution on Canal satellite and cable, but which never launched. During the summer of 1997, Thierry Ardisson produced Vue sur la mer, hosted by Maïtena Biraben.[36]

In 1998, he returned to France 2 (formerly Antenne 2) to host Tout le monde en parle alongside Laurent Ruquier, then Linda Hardy, Kad et Olivier and finally Laurent Baffie, on Saturday late night.[37]

During the summer of 1999, he co-hosted, alongside Laurent Ruquier, an episode of Le Grand Tralala, a late-night entertainment program in which the host or hosts were unaware of the show’s content.

2000s

[edit]In 2003, Thierry Ardisson launched Tribu[38] on France 2, a quarterly prime-time program that failed to attract viewers and was replaced in 2004 by Opinion publique, which met with no greater success.[39]

From 2003 to June 2007, he simultaneously hosted 93, faubourg Saint-Honoré on Paris Première, a dinner held at his own Parisian apartment during which he conversed with a panel of various celebrities.[40]

In 2004, he co-hosted a live broadcast on France 2 with Michel Drucker dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the Normandy landings. In 2005, again with Drucker and broadcast live, he presented Le Plus Grand Français de tous les temps[41] on France 2, and in September 2005, he co-produced Concerts sauvages on France 4.[42]

At the end of the 2005–2006 season, Ardisson left France 2 after a contractual disagreement (regarding his involvement with the competing TV channel, Paris Première).The new management of France Télévisions enforced the principle of exclusivity for public-service hosts after he signed with Paris Première for a new season of 93, faubourg Saint-Honoré. Ardisson refused to terminate his contract with Paris Première and was therefore forced to leave France Télévisions. In an open letter to Patrick de Carolis, Chairman and CEO of France Télévisions, in May 2006, Ardisson lamented his departure: “It’s a miracle you are killing.” [43] He pointed out that he had signed an exclusivity contract with France 2 preventing him from appearing on another terrestrial general-interest channel. However, Paris Première, a cable and satellite channel, was available on the encrypted pay-TV TNT package. France 2 nonetheless considered Paris Première to be a general-interest terrestrial channel and demanded enforcement of the exclusivity clause.[44]

Thierry Ardisson then joined the French semi-private TV network Canal+.[45] Starting on 4 November 2006, he produced, with Stéphane Simon, and hosted Salut les Terriens! every Saturday evening in early prime time on free-to-air.[46] The show attracted an average of 750,000 viewers in its first year.[47]

On 5 April 2008, to celebrate the host’s twenty years on television, the channel Jimmy broadcast a two-part documentary, Ardisson: 20 ans d'antenne, directed by Patrick Kieffer and Marie-Ève Chamard.[48]

2010s and 2020s

[edit]During the summer of 2010, he hosted Happy Hour,[49][50] a program that temporarily replaced Salut les Terriens !, mixing talk show and game-show formats. He also produced La télé est à vous[51] for France 2 during this period, hosted by Stéphane Bern. Beginning in December 2010, he presented Tout le monde en a parlé on channel Jimmy, revisiting the lives of individuals who had once been in the spotlight.The show aired three seasons.[52]

He returned with Happy Hour in December 2011, standing in for Le Grand Journal,[49] and again during the summer of 2012.[53]

In October 2014, while still hosting Salut les Terriens ! on Canal+, the program reached an audience of 1.4 million viewers,[47] making it the channel’s highest-rated show and one with “a loyal following” for many years.[25]

In 2015, Thierry Ardisson proposed to the channel M6 the script for Peplum, a humorous and anachronistic miniseries set in Ancient Rome. The host explained that he got the idea for the script from Peter Ustinov’s performance in Quo Vadis (1951).[54] The three 90-minute episodes were broadcast in prime time starting on 24 February 2015, at a rate of one per week.

The following year, he was the subject of a documentary, Génération Ardisson: 30 ans de télévision, before launching his new program Zéro limite. Meanwhile, businessman Vincent Bolloré, whom Ardisson openly supported despite the storm caused by the Canal+ shake-up, asked him to move his flagship show Salut les Terriens to the former D8 channel.

Beginning in September 2017, he hosted Les Terriens du dimanche! on C8, airing Sundays from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m., a spinoff of Salut les Terriens!.[55]

At the start of the 2018 season, Salut les Terriens! was renamed Les Terriens du samedi, with a new set and format. On 18 May 2019, Ardisson announced in a press release that he would no longer work for C8.[56] He recorded the last talk show of his career on Wednesday, 29 May 2019, which became the subject of a behind-the-scenes documentary offering viewers a glimpse of him off camera.[57] He justified his departure by citing the lack of resources provided by the channel, explaining that he “did not want to make low-cost television.”[58][59] In 2023, Ardisson revealed that he had also observed divergences with Vincent Bolloré, particularly political ones.[60]

At the end of August 2019, Thierry Ardisson sued, his former employer Vincent Bolloré at Canal+.[61] The host reacted to the cancellation of programs he had planned for the 2019 season, arguing that the decision had been announced far too late, causing harm to his production company.[61] Ardisson brought the case before the commercial court for “sudden rupture of economic dependence.” [62] After a court ruling and an appeal filed by Ardisson, the Court of Cassation ruled in 2021 that C8 must compensate Ardisson and his production partner Téléparis with 5 million euros.[63]

On 25 October 2020, INA launched a YouTube channel dedicated to Thierry Ardisson, Ina Arditube, featuring thousands of video excerpts from the presenter-producer’s shows.[64]

Following his departure from C8, Ardisson developed Hôtel du temps, a fictionalized interview program for France 3. In it, authentic words once spoken by a deceased celebrity, drawn from archival footage, are reworked and staged using deepfake technology.[65] The first episode, initially scheduled for September 2021 and featuring Jean Gabin,[66] was postponed and aired on 2 May 2022 with a 90-minute episode dedicated to Dalida.[67] Lower-than-expected ratings led Ardisson to delay the Gabin episode once again and instead produce one on Coluche, scheduled for filming in September 2022.[68] The Coluche episode was broadcast in June 2023 but, after disappointing viewership, the program was taken off the air. The show was nevertheless nominated at the 2023 International Emmy Awards in the category Best Non-Scripted Entertainment.

Ten months before his death in October 2024, during the shutdown of C8, the producer-presenter said he was delighted to see the channel disappear and settled scores with Canal+ boss Vincent Bolloré and fellow host-producer Cyril Hanouna.

Literary career

[edit]Thierry Ardisson has written and published three novels: Cinémoi (1972) and La Bible (1975) with Seuil, and Rive Droite (1983) with Albin Michel.

In 1986, he published Louis XX, Contre-enquête sur la Monarchie (Orban editor), which sold 100,000 copies.[69] On October 31, 1986, he appeared on Apostrophes in a debate with Max Gallo, where he defended the legacy of the French monarchy and sharply criticized the French Revolution as the origin of “totalitarianisms.” He compared Jacques-René Hébert to Robert Faurisson, accusing him of having distorted the circumstances of Louis XVI’s death.[70]

In 1994, he published Pondichéry with Albin Michel, recounting the story of a former colonial administrator who had lived in Pondicherry and was later repatriated to a housing estate in Sartrouville. Accused of “massive plagiarism” over several passages, the book caused a stir upon its release.[25]

In 2006, Ardisson released Confessions d'un baby-boomer with Flammarion, an autobiography written with Philippe Kieffer, which sold 100,000 copies.[71]

In 2016, he published Les Fantômes des Tuileries with Flammarion.[25]

In October 2024, he published L’Âge d’or de la pub with Éditions du Rocher.

Career in film

[edit]

In 2005, Ardisson created the Ardimages group to produce feature films and television series.[72]

In 2007, he made an appearance in the French-Quebecois film Days of Darkness (L'Âge des ténèbres) by Denys Arcand. He played himself on the set of Tout le monde en parle.

In 2012, Ardisson produced his first feature film, Max, directed by Stephanie Murat with Joey Starr and Mathilde Seigner, and distributed by Warner Bros.[73][74]

In 2013, Ardisson began producing a second feature film, Memories directed by Jean-Paul Rouve and starred Michel Blanc, Annie Cordy, Chantal Lauby and Audrey Lamy.[75]

In 2015, he produced Comment c'est loin, a feature film directed by Orelsan and Christophe Offenstein. The following year, he produced a film retracing the golden years of Le Palace.

In 2018, he produced Ma fille, a feature film directed by Naidra Ayadi and inspired by Bernard Clavel’s novel Le voyage du père, which follows a father’s journey to Paris in search of his daughter.

At the same time, he also worked as a producer on television documentaries.[25]

Career in radio

[edit]On 29 August 2014 Ardisson joined Laurent Ruquier’s "Les Grosses Têtes" on RTL.[76]

Personal life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

Thierry Ardisson married Christiane Bergognon in June 1970. Shortly afterward, he discovered that she was cheating on him[77] and attempted suicide by slashing his wrists in a bathtub; he was saved just in time.[78]

In 1974, during a trip to Bali with his wife, they were introduced to the use of drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and hallucinogenic mushrooms. Thierry Ardisson has publicly spoken several times about his drug use.[77]

On April 2, 1988, he married Béatrice Loustalan, a sound designer. The couple had three children: two daughters, born in 1989 and 1991, and a son, born in 1996.[79] In August 2010, Béatrice Ardisson announced their separation.[80]

Beginning in November 2009, he was in a relationship with French journalist Audrey Crespo-Mara,[81][82] whom he married on June 21, 2014.[83] The couple remained together until his death.

In 2018, Thierry Ardisson stated in an interview with Le Journal du dimanche that he earned “between 15,000 and 20,000 euros per month.” He added: “If I do too much television at the expense of more noble activities, it’s because I am venal; I love money.[84]”

Political views

[edit]Ardisson described himself as a royalist, more specifically a supporter of constitutional monarchy in the style of the Westminster system. Louis de Bourbon, Duke of Anjou and legitimist pretender to the throne of France, is the godfather of his daughter Ninon.[48]

Death

[edit]Thierry Ardisson died[85][86][87] on 14 July 2025 at the age of 76 at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. He had been diagnosed with liver cancer in 2012.[88][89] Shortly before the official announcement, a rumor of his death circulated on social media, spread by blogger Clément Garin. In response, Audrey Crespo-Mara announced her intention to pursue legal action[90][91]

His funeral took place on 17 July 2025 at the Church of Saint-Roch in the 1st arrondissement of Paris. The farewell private ceremony was conducted by Father Daniel Duigou and Father Henri Imbert and followed a black dress code, in accordance with his wishes. Thierry Ardisson was buried on 19 July 2025 at the Ménerbes cemetery in the Vaucluse region.

Controversies

[edit]In February 1994, he admitted to having plagiarized 70 lines in his first book, Pondichéry. In 2005, an investigation by Jean Robin revealed that Thierry Ardisson had indeed committed plagiarism in several works: Désordres à Pondichéry by Georges Delamarre (1937), De Lanka à Pondichéry by Douglas Taylor (1931), and Créole et Grande Dame by Yvonne Gaebelé (1956) — totaling about sixty pages overall.[92][93][94]

During the 16 March 2002 broadcast of his show Tout le Monde en Parle (France 2), he invited writer Thierry Meyssan to discuss his book L'Effroyable Imposture (The Big Lie). In this work, Meyssan presents the September 11, 2001 attacks as having been orchestrated by “a segment of the U.S. military-industrial complex” rather than the terrorist organization Al-Qaeda, whose leader, Osama bin Laden, is described as “a CIA fabrication,” which allegedly never ceased collaborating with U.S. Secret services. In the days following the broadcast, this promotion of the conspiracy-laden book was heavily criticized. The host was reproached for not providing any counterpoints to Meyssan’s presentation, effectively presenting the book as a “truthful account.” The CSA (French Media Authority Council) sent a letter to the president of France Télévisions warning that the host “had adopted [the book] as his own, without any critical distance or careful wording, propagating information that was clearly false, after explicitly granting the author legitimacy and respectability…” The organization reminded the director of the network’s obligations, demanded a restoration of the truth, and that no further lapses occur.[95][96][97][98]

In September 2006, Jean Birnbaum and Raphaël Chevènement published the book La face visible de l'homme en noir, in which they criticized the presenter for, among other things, using his show Tout le Monde en Parle to reproduce international intercommunal tensions (particularly regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) and thereby promoting them in France. They cited Dieudonné as an example and suggested that Ardisson’s leading questions may have gradually pushed him toward extreme communal positions.[92] The authors also criticized Ardisson’s editing practices, accusing him of shaping the discourse of his show, which was broadcast in a shortened, delayed format compared to the original recording.[99]

In February 2008, Ardisson was included among the “Animatueurs” lampooned in Michel Malaussena’s book, which revisited his years of collaboration with Thierry Ardisson and discussed his sometimes authoritarian, vindicative personality. In the press, he was described as a meticulous and precise presenter, unafraid to write hundreds of notes for each show; “I am very organized,” he stated.[25]

In 2020, a 1995 video clip sparked controversy: it shows Ardisson joking with Frédéric Beigbeder and Gabriel Matzneff about sexual relations they imagined with “twelve-and-a-half-year-old girls.”[100]

On May 10, 2025, on the set of the show Quelle époque!, he stated, “Gaza is Auschwitz, that’s it, that’s all there is to say,” remarks condemned by the LICRA and CRIF. The next day, he issued an apology to “his Jewish friends” via a statement to AFP.[101][102]

Broadcasts

[edit]Regular broadcasts

[edit]- 1985 : Descente de police on TF1

- 1985–1986 : Scoop à la une on TF1

- 1987–1988 : Bains de minuit on La Cinq[103]

- 1988–1990 : Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches on Antenne 2

- 1990–1991 : Télé zèbre on Antenne 2

- 1991–1992 : Double jeu on Antenne 2

- 1992 : Le bar de la plage on Antenne 2

- 1993 : Ardimat on France 2

- 1994 : Autant en emporte le temps on France 2

- 1994 : Long courrier on France 2

- 1995–1997 : Paris Dernière on Paris Première

- 1997–2004 : Rive droite / Rive gauche on Paris Première

- 1998–2006 : Tout le monde en parle on France 2

- 2001–2002 : Ça s'en va et ça revient on France 2

- 2003–2004 : Opinion publique on France 2

- 2003–2007 : 93, faubourg Saint-Honoré on Paris Première

- 2010–2014 : Happy Hour on Canal+

- Since 2006 : Salut les Terriens ! on Canal+

- Since 2010 : Tout le monde en a parlé on Jimmy

Special broadcasts

[edit]- June 1990 : Rolling Stones : les jumeaux impossibles on Antenne 2

- January 1993 : Cœur d'Ardishow on France 2

- 2001 : La Nuit Gainsbourg on France 2

- October 2002 : Bedos/Ardisson : on aura tout vu ! on France 2

- 2002 : Le père noël n'est pas une ordure on France 2

- June 2002 : Spéciale Maillan-Poiret on France 2

- April 2003 : Le Grand Blind Test on France 2

- 2004 : 60e anniversaire du Débarquement (avec Michel Drucker) on France 2

- April and May 2005 : Le Plus Grand Français de tous les temps on France 2

- April 2008 : Ardisson : 20 ans d'antenne on Jimmy

Bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson, Cinemoi, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, coll. « Cadre Rouge », October 1, 1973 (ISBN 2020012243)

- Thierry Ardisson, La Bilbe, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1975 (ISBN 9782020042253)

- Thierry Ardisson, Rive droite, Paris, Éditions Albin Michel, February 11, 1983, 216 p. (ISBN 2226016848)

- Thierry Ardisson, Pondichéry, Éditions Albin Michel, January 1, 1993 (ISBN 978-2226061171).

Essays

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson, Louis XX – Contre-enquête sur la Monarchie 1986 (ISBN 2855653347), sold over 100,000 copies.[104]

- Thierry Ardisson, Louis XX, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, coll. « Folio », 11 mars 1988, 249 p. (ISBN 2070379124)

- Thierry Ardisson, Pondichéry, 1994 (ISBN 2226061177)

- Thierry Ardisson, Le Petit livre blanc. Pourquoi je suis monarchiste, Paris, Plon, 4 octobre 2012 (ISBN 978-2259217484)

In Collaboration

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Rock Critics, Paris, Don Quichotte, 6 mai 2010, 304 p. (ISBN 9782359490169)

- With Cyril Drouet & Joseph Vebret, Dictionnaire des provocateurs, Paris, Plon, 25 novembre 2010 (ISBN 2259212131)

- With Anne Saint Dreux, Paris-Monaco, éditions du Rocher, 16 octobre 2024, 144 p.(ISBN 978-2268111063)

Autobiography

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson, Les années provoc, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, coll. « Docs Témoignage », 1er novembre 1998, 347 p. (ISBN 2080676350)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Confessions d'un babyboomer, Paris, Flammarion, 15 octobre 2004, 358 p. (ISBN 208068583X)

Contributions

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Dix ans pour rien ? Les années 80, Paris, Éditions du Rocher, coll. « Lettre recommandée », 1990 (ISBN 2268009114)

- Thierry Ardisson (postface), Peut-on penser à la télévision ? La Culture sur un plateau, Paris, Éditions Le Bord de l'eau/INA, coll. « Penser les médias », 2010, 290 p. (ISBN 2356870644)

Television

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson & Laurent Baffie, Tu l'as dit Baffie ! Concentré de vannes, Paris, Le Cherche midi, coll. « Le Sens de l'humour », 21 April 2005 (ISBN 2749103851)

- Thierry Ardisson & Jean-Luc Maître, Descentes de police, Paris, Love Me Tender/Business Multimedia, 1984, 139 p. (ISBN 2749101441)

- Thierry Ardisson (collectif), Paris dernière. Paris la nuit et sa bande son, Paris, M6 Éditions, 10 November 2010, 320 p. (ISBN 2915127808)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Tout le monde en a parlé, Paris, Flammarion, 2012, 360 p. (ISBN 9782081221260)

- Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Magnéto Serge !, Paris, Flammarion, 2013, 300 p. (ISBN 9782081280298)

Videography

[edit]- Thierry Ardisson, Paris interdit. Découvrez les endroits les plus interdits de Paris, documentaire, 1997. (VHS)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Double Jeu, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSOM)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Lunettes Noires pour Nuits Blanches, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSO2)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Tout le monde en parle, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSOW)

- Thierry Ardisson, La Boite noire de l'homme en noir, Arcades Vidéo, 2010. (ASIN B00443PSNS)

- Thierry Ardisson, Les Années Paris Première, M6 Vidéo, 2011. (ASIN B005JYUWSW)

- Collectif, Où va la création audiovisuelle, BnF/Ina, 201168.[105]

Music

[edit]- Instant Sex. Le Disque souvenir de l'émission culte Double Jeu de Thierry Ardisson, vinyle, 1993.

- La Musique de Tout le monde en parle, compilation, Naïve, 2002.

He is cited in a song by Renaud, Les Bobos : « Ardisson et son pote Marco » (reference to Marc-Olivier Fogiel).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Thierry Ardisson Biography". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ puremedias (2 November 2011). "Thierry Ardisson P1 : "Je ne suis pas assez con pour penser qu'il n'y a que moi qui ai de bonnes idées"". www.ozap.com. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ Perrin, Elisabeth (28 May 2004). "La télé refait le D-Day". Le Figaro.

- ^ "Max (I) (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Sinistrose | Immédias - Lexpress" (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Pour qui votez-vous Thierry Ardisson ?" [Who are you voting for, Theirry Ardisson?]. Revue Charles (in French). 21 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ Thierry Ardisson & Philippe Kieffer, Confessions d'un baby boomer, 2004, p. 29

- ^ Ardisson, Thierry (2006). Confessions d'un baby-boomer. Éditions Grasset.

- ^ a b c Technikart. "Ex-fan des eighties". Technikart. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Emmanuel, Berretta. "Thierry Ardisson, de A à Zèbre". Le Point. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ ""On gagnait des fortunes !" : Tropico, Lapeyre, Ovomaltine... Ces slogans mythiques de la pub imaginés par Thierry Ardisson". Franceinfo (in French). 14 July 2025. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Elidia, Groupe. "L'âge d'or de la pub - Éditions du Rocher". editionsdurocher.fr (in French). Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "«Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches» : un vent de liberté". Le Figaro (in French). 17 August 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Chaussée aux moines : Prêche gustatif - Stratégies". Stratégies (in French). 23 October 2003. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ "Resultat: Avez-vous la mémoire des slogans publicitaires ?". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Garrigos, Raphaël. "De Warhol à Laetitia Casta". Liberation. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Fontaine, Gilles. "" J'économise " cartonne". L'Expansion. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Plateau Thierry Ardisson". ina.fr. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Raveleau, Alexandre (4 April 2008). "Thierry Ardisson fête ses 20 ans de télévision". Toutelatele (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Télé 7 Jours (2497): 27.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Scoop à la Une (1985–1986)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "À la folie, pas du tout (1987)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Bains de minuit (1987–1988)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Lunettes noires pour nuits blanches (1988–1990)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Baudrillet, Marc (22 September 2016). "Inusable". Challenges. 490: 60–63.

- ^ "Stars à la barre (1988–1990)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Télé-Zèbre (1990– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "VIDEO Yvan Le Bolloc'h' raconte comment il a rencontré Bruno Solo". Voici.fr (in French). 23 April 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ "Quand Thierry Ardisson passe aux aveux". Le Point. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Frou-Frou (1992–1994)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Graines de star (1996– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ BOULAY, Anne. "Sélection. Les Cinq Dernières Minutes. Graines de star. Récolte sanglante. Dossier secret du triple meurtre au Mississippi". Libération (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ PSENNY, Daniel; VIVIANT, Arnaud. "Laurent Ruquier mort de rire. Patrick Le Lay stoppe «les Niouzes» après une semaine". Libération (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ "Paris dernière (1999– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Rive droite – rive gauche (1997– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Agostini, Joseph (31 January 2005). "Maïtena Biraben". Toutelatele (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ "Tout le monde en parle (1998–2006)". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Tribus : tout le monde va en parler". ladepeche.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ à 00h00, Par Stéphane Lepoittevin Le 15 décembre 2003 (14 December 2003). "Thierry Ardisson veut séduire les ménagères". leparisien.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "93 Faubourg Saint-Honoré (2003– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Les dix plus grands Français de tous les temps". Le Nouvel Obs (in French). 18 March 2005. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Raveleau, Alexandre (9 September 2005). "France 4 et France 5 : une rentrée dans la continuité". Toutelatele (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ "«C'est un miracle que tu fusilles»". Libération (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ GARRIGOS, Raphaël; ROBERTS, Isabelle. "Ardisson: France 2, on n'en parle plus". Libération (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Garrigos, Raphaël; Roberts, Isabelle. "C'est un miracle que tu fusilles". Liberation fr. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Salut les Terriens (2006– )". IMDb. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b Kessous, Mustapha (24 October 2014). "Thierry Ardisson : " Quand vous êtes créateur en France, vous vous demandez à quoi vous servez "". Le Monde.fr. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Thierry Ardisson fête ses 20 ans d'antenne : retour sur la carrière de 'l'homme en noir'". Purepeople.com (in French). Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ a b "TVMag.com - Programmes TV - Happy Hour cet été pour Ardisson - Jeux". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "TVMag.com - Programmes TV - Happy Hour cet été pour Ardisson - Jeux". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Bern décroche une quotidienne estivale". Le Figaro. 13 April 2010.

- ^ "Ardisson animera "Tout le monde en a parlé" sur Jimmy". jeanmarcmorandini. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ VERDREL, Jean-Marc (6 June 2012). "Assistez aux tournages de "Happy Hour" avec Thierry Ardisson de retour". Les coulisses de la télévision (in French). Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Télévision: une série humoristique proposée par Ardisson, "Peplum", sur M6". LExpansion.com (in French). 22 February 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ puremedias (10 September 2017). ""Les Terriens du dimanche" : Thierry Ardisson décline "Salut les Terriens !" dès ce soir sur C8". www.ozap.com. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ puremedias (18 May 2019). "Thierry Ardisson quitte C8". www.ozap.com. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ INA Arditube (25 October 2020). Terriens, la dernière valse : les coulisses de la dernière de Salut Les Terriens ! | INA Arditube. Retrieved 18 September 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson annonce qu'il quitte C8 pour ne pas faire du «low cost»". Le Figaro (in French). 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson claque la porte de C8 : "Je ne veux pas faire de la télé low cost"". TF1 INFO (in French). 20 May 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ ""Pas envie d'être assimilé à l'extrême droite": Thierry Ardisson revient sur son départ de Canal+". RMC (in French). 23 June 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ a b anneyasmine-machet (28 August 2019). "Thierry Ardisson assigne Vincent Bolloré en justice pour rupture brutale de dépendance économique". Télé Star (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ puremedias (29 August 2019). "Thierry Ardisson attaque C8 pour "parasitisme" et "rupture brutale de dépendance économique"". www.ozap.com. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "C8 condamnée à verser 5 millions d'euros à Ardisson". Le HuffPost (in French). 10 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Ina Arditube: Une nouvelle chaîne YouTube dédiée à Thierry Ardisson". La Presse (in Canadian French). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ Rédaction, La (2 May 2022). "Le deepfake institutionnalisé par Thierry Ardisson avec l'émission "Hôtel du temps"". Science infused site d'actualités (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson "ressuscite les morts "dans son émission "Hôtel du temps"". ladepeche.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Des stars défuntes se racontent face à Ardisson dans "Hôtel du temps"". ladepeche.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson « abattu » face à l'échec d'« Hôtel du temps »". 20 Minutes (in French). 28 May 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2025.

- ^ Perrin, Elisabeth (28 May 2004). "La télé refait le D-Day". Le Figaro.

- ^ A bas le roi ! Vive le roi ! | INA (in French). Retrieved 1 September 2025 – via www.ina.fr.

- ^ Revel, Renaud (13 May 2008). "Sinistrose". L'Express.

- ^ Gonzales, Paule (19 May 2008). "Thierry Ardisson se lance dans le cinéma". Le Figaro. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson coproduit son premier film". Le Figaro. November 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Bruno, Maxime (2 November 2011). "Thierry Ardisson produit son premier film, Max". L'Express. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Annie Cordy et Audrey Lamy plongent dans les Souvenirs de Jean-Paul Rouve". PurePeople.com. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Franz-Olivier Giesbert et Thierry Ardisson rejoignent Laurent Ruquier". RTL.fr. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b Seront, Frédéric (17 September 2025). ""Je me défonçais du matin au soir"". DHnet (in French). Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "La tentative de suicide de Thierry Ardisson - Extrait vidéo Le divan de Marc-Olivier Fogiel". www.france.tv (in French). Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Terrafemina (6 March 2014). "Thierry Ardisson : Audrey, Béatrice, Manon et Ninon, les femmes de sa vie". www.terrafemina.com. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Purepeople (6 August 2010). "Béatrice Ardisson, la femme de Thierry confie : "Je suis en plein divorce..."". www.purepeople.com. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Exclu Gala- Thierry Ardisson et Audrey: « Entre nous, c'est un coup de foudre »". Gala (in French). 25 June 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson : Son mariage surprise avec Audrey Crespo-Mara". Femme Actuelle.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson : son mariage surprise avec Audrey Crespo-Mara - Femmeactuelle.fr". www.femmeactuelle.fr (in French). 25 June 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Combien gagne le "vénal" Thierry Ardisson ? Il répond !". 15 April 2018.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson, l'animateur et producteur de télévision est mort à 76 ans". www.rtl.fr (in French). 14 July 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson, animateur et producteur de télévision, grand provocateur, est mort à l'âge de 76 ans" (in French). 14 July 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Paul, Émilie (14 July 2025). "Mort de Thierry Ardisson, l'irrévérencieux homme en noir". TV Magazine (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson, animateur et producteur de télévision, grand provocateur, est mort à l'âge de 76 ans". Le Monde. 14 July 2025. Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ "« Je crois à ma bonne étoile » : le testament de Thierry Ardisson". parismatch.com (in French). 16 July 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Mort de Thierry Ardisson : Audrey Crespo-Mara annonce attaquer en justice celui qui a annoncé à tort la mort de son mari". www.rtl.fr (in French). 14 July 2025. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Laratte, Aubin (14 July 2025). "Mort de Thierry Ardisson : sa femme, Audrey Crespo-Mara, annonce une action en justice contre le journaliste Clément Garin". leparisien.fr (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ a b Schneidermann, Daniel. "Paysage de l'après-Ardisson". Libération (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson: du plagiat à l'échelle industrielle". L'Hebdo: 90–91. 27 October 2005.

- ^ "Thierry Ardisson : douze ans de mensonges". Entrevue (160): 97–101. 16 May 2005.

- ^ Interview vérité de Thierry Meyssan (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2025 – via www.ina.fr.

- ^ Lagrange, Pierre (2002). "Quels arguments opposer aux amateurs de conspirations ?". Mouvements (in French). 24 (5): 113–119. doi:10.3917/mouv.024.0113. ISSN 1291-6412.

- ^ Bouzet, Ange-Dominique. "L'effroyable escroquerie". Libération (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Emission Tout le monde en parle : courrier à France 2 - Arcom (ex-CSA)". www.csa.fr (in French). 2002. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ mathieu-helene (27 February 2023). "Jean-Hugues Anglade : "Je prends soin de mon corps parce qu'il a été maltraité"". Psychologies.com (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Beigbeder s'explique sur ces archives de 1995 le montrant plaisanter avec Matzneff". Le HuffPost (in French). 21 February 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ La-Croix.com (11 May 2025). "Tollé du Crif et de la Licra après des propos d'Ardisson sur la situation à Gaza". La Croix (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Pour Aurore Bergé, les propos de Thierry Ardisson comparant Gaza à Auschwitz «nourrissent l'antisémitisme»". Le Figaro (in French). 13 May 2025. Retrieved 31 August 2025.

- ^ "Bains de minuit". Toutelatele.com. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Perrin, Élisabeth. "La télé refait le D-Day". TV Mag. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ [video] Broadcast Tout le monde en parle, 8

External links

[edit] Media related to Thierry Ardisson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thierry Ardisson at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Thierry Ardisson at IMDb

- Thierry Ardisson discography at Discogs