The Concept of Anxiety

Danish title page to The Concept of Anxiety | |

| Author | Søren Kierkegaard (as Vigilius Haufniensis) |

|---|---|

| Original title | Begrebet Angest |

| Translator | Reidar Thomte |

| Language | Danish |

| Subject | |

Publication date | June 17, 1844 |

| Publication place | Denmark |

Published in English | 1946 |

| Media type | paperback |

| Pages | ~162 |

| ISBN | 0-691-02011-6 |

| Preceded by | Prefaces |

| Followed by | Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 |

The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin (Danish: Begrebet Angest. En simpel psychologisk-paapegende Overveielse i Retning af det dogmatiske Problem om Arvesynden) is a philosophical work written by Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in 1844. It explores the concept of anxiety as it relates to human freedom, original sin, and existential choice.

The original 1944 English translation by Walter Lowrie (now out of print), was titled The Concept of Dread.[1] The Concept of Anxiety was dedicated "to the late professor Poul Martin Møller". Kierkegaard used the pseudonym Vigilius Haufniensis (which, according to Josiah Thompson, is the Latin transcription for "the Watchman"[2][3] of Copenhagen) for The Concept of Anxiety.[4]

Themes and analysis

[edit]The Concept of Anxiety was published on June 17, 1844, the same date as Prefaces' publication. Both books deal with Hegel's idea of mediation.

Kierkegaard mentions that anxiety is a way for humanity to be saved as well. Anxiety informs us of our choices, our self-awareness and personal responsibility, and brings us from a state of un-self-conscious immediacy to self-conscious reflection. (Jean-Paul Sartre calls these terms pre-reflective consciousness and reflective consciousness.)[5]

Progress

[edit]

Kierkegaard states that "anxiety about sin produces sin".[8] In Stages on Life's Way, he discusses repentance as "a recollection of guilt" and argues that "the ability to recollect is the condition for all productivity." He explains that if a person wishes to avoid being productive, they need only "remember the same thing that recollecting he wanted to produce, and production is rendered impossible."[9]

Philosophers were involved with the dialectical question of exactly "how" an individual or group changes from good to evil or evil to good. Kierkegaard pressed forward with his category of "the single individual."[10] In his journals, Kierkegaard interprets Peter's words "To whom shall we go?"[11] as referring to Peter's consciousness of sin, suggesting that "it is this that binds a man to Christianity" and that God "determines every man's conflicts individually".[12]

Supernaturalism

[edit]

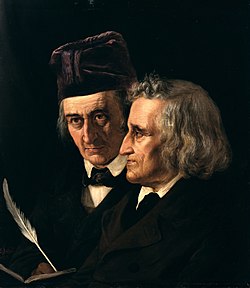

The Brothers Grimm wrote about the use of folktales as educational stories to keep individuals from falling into evil hands. Kierkegaard refers to The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was in The Concept of Anxiety (p. 155).[13]

Kierkegaard felt that imaginative constructions should be upbuilding. He wrote about "the nothing of despair",[14] God as the unknown is nothing,[15] and death is a nothing.[16] Goethe's Der Erlkönig and The Bride of Corinth (1797)[17] are also nothing. Many things are hard to understand but Kierkegaard says, "Where understanding despairs, faith is already present in order to make the despair properly decisive."[18]

The first sin

[edit]

Kierkegaard is not concerned with what Eve's sin was; he says it was not sensuousness,[19] but he is concerned with how Eve learned that she was a sinner. He says "consciousness presupposes itself".[20] Eve became conscious of her first sin through her choice and Adam became conscious of his first sin through his choice. God's gift to Adam and Eve was the "knowledge of freedom" and they both decided to use it.[21] In Kierkegaard's Journals he said, "the one thing needful" for the doctrine of Atonement to make sense was the "anguished conscience." He wrote, "Remove the anguished conscience, and you may as well close the churches and turn them into dance halls."[22]

Kierkegaard says, every person has to find out for him or her self how guilt and sin came into their worlds. Kierkegaard argued about this in both Repetition and Fear and Trembling where he said philosophy must not define faith.[23]

Kierkegaard observes that it was the prohibition itself not to eat of the tree of knowledge that gave birth to sin in Adam. He questions the doctrine of Original Sin, also called Ancestral sin., "The doctrine that Adam and Christ correspond to each other confuses things. Christ alone is an individual who is more than an individual. For this reason he does not come in the beginning but in the fullness of time."[24] Sin has a "coherence in itself".[25]

Kierkegaard also writes about an individual's disposition in The Concept of Anxiety. He was impressed with the psychological views of Johann Karl Friedrich Rosenkranz:

In Rosenkranz's Psychology there is definition of disposition [Gemyt]. On page 322 he says that disposition is the unity of feeling and self-consciousness. Then in preceding presentation he superbly explains "that the feeling unfolds itself to self-consciousness, and vice versa, that the content of the self-consciousness is felt by the subject as his own. It is only this unity that can be called disposition. If the clarity of cognition is lacking, knowledge of the feeling, there exists only the urge of the spirit of nature, the turgidity of immediacy. On the other hand, if feeling is lacking, there remains only the abstract concept that has not reached the last inwardness of the spiritual existence, that has not become one with the self of the spirit." (cf. pp. 320–321) If a person now turns back and pursues his definition of "feeling" as the spirit's immediate unity of its sentience and its consciousness (p. 142) and recalls that in the definition of Seelenhaftigkeit [sentience] account has been taken of the unity with the immediate determinants of nature, then by taking all this together he has the conception of a concrete personality. [but, Kierkegaard says] Earnestness and disposition correspond to each other in such a way that earnestness is a higher as well as the deepest expression for what disposition is. Disposition is the earnestness of immediacy, while earnestness, on the other hand, is the acquired originality of disposition, its originality preserved in the responsibility of freedom and its originality affirmed in the enjoyment of blessedness.

— Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety, p. 148

Contemporary reception

[edit]Walter Lowrie translated The Concept of Dread in 1944. He was asked "almost petulantly" why it took him so long to translate the book. Alexander Dru had been working on the book, and Charles Williams hoped the book would be published along with The Sickness unto Death, which Lowrie was working on in 1939. After the war started, Dru was wounded and gave the job over to Lowrie. Lowrie could find no adequate word to use for Angst. Lee Hollander had used the word dread in 1924, a Spanish translator used angustia, and Miguel Unamuno, writing in French used agonie while other French translators used angoisse.[26] Rollo May quoted Kierkegaard in his book Meaning of Anxiety, which is the relation between anxiety and freedom.

I would say that learning to know anxiety is an adventure which every man has to affront if he would not go to perdition either by not having known anxiety or by sinking under it. He therefore who has learned rightly to be anxious has learned the most important thing.— Kierkegaard, The Concept of Dread.[27]

Robert Harold Boethius, in his 1948 book Christian Paths to Self-Acceptance, discusses Kierkegaard's concept of dread, explaining that the distorted doctrines of man's depravity from the Reformation and Protestant scholasticism are clarified by neo-orthodox theologians. While sin is often preached in undialectical forms, Kierkegaard offers a modern reinterpretation, linking sin to anxiety. He explains that "dread or anxiety" precedes sin, coming close to it but without fully explaining it, which only breaks forth through a "qualitative leap." Kierkegaard views this "sickness unto death" as central to human existence, teaching that a "synthesis" with God is necessary for resolving inner conflicts and achieving self-acceptance.[28]

In 1958, George Laird Hunt interpreted Kierkegaard's writing as basically asking "How can we understand ourselves?" and wrote:

Kierkegaard views man’s humanity through his creatureliness, defined by his position between life and death. Made in God's image, man feels the presence of eternity but also knows his inevitable death. This tension creates his anguish and possibility of immortality. Man sins by avoiding faith and the uncertainty of existence, either denying death or rejecting eternity. He refuses to face the anguish of being both mortal and dependent on God. True humanness lies in acknowledging both life and death, which marks the beginning of redemption.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Kierkegaard wrote again about dread in his 1847 book Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, translated by Howard Hong

Alas, although many call themselves Christians and yet may seem to be living in uncertainty as to whether God actually is love, it would truly be better if they made the love blaze just by the thought of paganism's horror: that he who holds the fate of everything and also your fate in his hand is ambivalent, that his love is not a fatherly embrace but a constraining trap, that his secret nature is not eternal clarity but concealment, that the deepest ground of his nature is not love but a cunning impossible to understand. We are not, after all, required to be able to understand the rule of God's love, but we certainly are required to be able to believe and, believing, to understand that he is love. It is not dreadful that you are unable to understand God's decrees if he nevertheless is eternal love, but it is dreadful if you could not understand them because he is cunning. If, however, according to the assumption of the discourse, it is true that in relation to God a person is not only always in the wrong but is always guilty and thus when he suffers also suffers as guilty-then no doubt within you (provided you yourself will not sin again) and no event outside you (provided you yourself will not sin again by taking offense) can displace the joy. Soren Kierkegaard, Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Hong pp. 267–269

- ^ Prefaces/Writing Sampler, Nichol pp. 33–34, 68 The Concept of Anxiety pp. 115–116

- ^ Kierkegaard presents an Either/Or here:

"Son of man, I have made you a watchman for the house of Israel; whenever you hear a word from my mouth, you shall give them warning from me. If I say to the wicked, 'You shall surely die,' and you give him no warning, nor speak to warn the wicked from his wicked way, in order to save his life, that wicked man shall die in his iniquity; but his blood I will require at your hand. But if you warn the wicked, and he does not turn from his wickedness, or from his wicked way, he shall die in his iniquity; but you will have saved your life. Again, if a righteous man turns from his righteousness and commits iniquity, and I lay a stumbling block before him, he shall die; because you have not warned him, he shall die for his sin, and his righteous deeds which he has done shall not be remembered; but his blood I will require at your hand. Nevertheless if you warn the righteous man not to sin, and he does not sin, he shall surely live, because he took warning; and you will have saved your life." Ezekiel 3:17–19 The Bible

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/r/rsv/rsv-idx?type=DIV1&byte=3114629"The end of all things is near. Therefore be clear minded and self-controlled so that you can pray. Above all, love each other deeply, because love covers over a multitude of sins. Offer hospitality to one another without grumbling. Each one should use whatever gift he has received to serve others, faithfully administering God's grace in its various forms. If anyone speaks, he should do it as one speaking the very words of God. If anyone serves, he should do it with the strength God provides, so that in all things God may be praised through Jesus Christ. To him be the glory and the power for ever and ever. Amen. Dear friends, do not be surprised at the painful trial you are suffering, as though something strange were happening to you." 1 Peter 4:7–12 Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- ^ Kierkegaard Josiah Thomson Alfred A Knopf 1973 pp. 142–143

- ^ Kierkegaard wrote against prereflection and how it can keep the single individual from acting in his book Two Ages, The Age of Revolution and the Present Age, A Literary Review, 1845, Hong 1978, 2009 pp. 67–68

- ^ See Marxist.org for Hegel's book

- ^ Kierkegaard discusses Herbart in relation to the question of whether an individual would begin with the negative or the positive: "The question of whether the positive or the negative comes first is exceedingly important, and the only modern philosopher who has declared himself for the positive is presumably Herbart." The Concept of Anxiety, Thomte p. 143

- ^ The Concept of Anxiety, p. 73

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Stages on Life's Way, Hong translation, p. 14, 1845.

- ^ See Kierkegaard, Søren. Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Hong translation, pp. 141–154, 1847.

- ^ "John 6:68". Bible Hub. Retrieved 2025-03-07.

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Journals and Papers, IX A 310; J820, Croxall translation Meditations from Kierkegaard, p. 119.

- ^ See Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- ^ Either/Or Part II p. 198-199

- ^ Philosophical Fragments, Swenson p. 30, The Concept of Anxiety p. 12-13, Three Discourses On Imagined Occasions, Søren Kierkegaard, June 17, 1844, Hong 1993 p. 13-14

- ^ Three Discourses On Imagined Occasions, p.90-97

- ^ The Vampire Female: The Bride of Corinth (1797) by: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

- ^ Concluding Unscientific Postscript, p. 220-230

- ^ The Concept of Anxiety p. 57-60

- ^ Journals and Papers, Hannay, 1996 1843 IVA49

- ^ The Concept of Anxiety p. 44-45

- ^ Journals of Søren Kierkegaard, VIII 1A 192 (1846) (Works of Love), Hong p. 407

- ^ The Concept of Anxiety p. 29-31, Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, Hong p. 11-14

- ^ The Concept of Anxiety Note p. 33, There is an eternal difference between Christ and every Christian. Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, Hong 1995 p. 101

- ^ Søren Kierkegaard, Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions p. 31-32

- ^ The Concept of Dread, Walter Lowrie Princeton University May 26, 1943 his preface to the book

- ^ Preface to Meaning of Anxiety & p. 32

- ^ Bonthius, Robert H. (1948). Christian paths to self-acceptance. New York: King's Crown Press.

Bibliography

[edit]- Søren Kierkegaard The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin June 17, 1844 Vigilius Haufniensis, Edited and translated by Reidar Thomte Princeton University Press 1980 Kierkegaard's Writings, VIII ISBN 0691020116

- Søren Kierkegaard "The Concept of Anxiety" 1844, translation by Alastair Hannay, March 2014 Kirkus Review

- Søren Kierkegaard The Concept of Anxiety The only book by Kierkegaard in audio format (Hannay translation)

- Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety, Introduction, Marxists.org

- Johann Karl Friedrich Rosenkranz, Rosenkranz's Philosophy of Education (February 18, 1887), Science, Vol. 9

- Anthony D. Storm, Anthony D. Storm's Commentary on The Concept of Anxiety

External links

[edit] Quotations related to The Concept of Anxiety at Wikiquote

Quotations related to The Concept of Anxiety at Wikiquote- Walter Lowrie, The Concept of Dread free text from archive.org

- Arne Grøn, The Concept of Anxiety in Soren Kierkegaard Mercer University Press, Oct 1, 2008 Retrieved 1/15/2012

- Walter Kaufmann, Kierkegaard and the Crisis in Religion 1960 Audio Archive.org

- Rollo May, The Meaning of Anxiety 1950, 1996 p. 170ff

- Professor Alison Assiter, Kierkegaard and Kant on Freedom and Evil, YouTube

- Dr. Patrick McCarty, Anxiety: Its Source, Nature, Solution Audio about The Concept of Anxiety from Archive.org

- Henrik Stangerup, The Man Who Wanted To Be Guilty July 2000

- Arland Ussher, Journey Through Dread: A Study of Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Sartre 1955