Portuguese–Safavid relations

Portugal |

Iran |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Expanding influence in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf, including Hormuz | Potential alliance with Portugal against its neighbors, particularly the Ottoman Empire, as well as control over Hormuz |

Portuguese–Safavid relations extended beyond Iran's borders as both nations engaged in official and unofficial interactions across the Middle East, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, and India. Safavid Iran was regarded by the Portuguese Empire as a potential ally to deter rival powers from using the Persian Gulf against its interests in the Indian Ocean. At the same time, the Portuguese-ruled parts of India viewed the efforts of the Safavid dynasty to spread Shia Islam as a threat and acted to prevent a possible Shia alliance against their territories.[1]

Political history

[edit]

Portuguese knowledge and information about the Iranian world were limited and mostly outdated before their first meeting with Safavid authorities near the Hormuz Island in 1507. Due to the writings of Marco Polo, the Portuguese had some information about Ilkhanate Iran. As Portugal's trading networks expanded across the Mediterranean Sea in the 15th century, they gained more knowledge about Iran. It was first in 1489 that the Portuguese directly interacted with the Iranian world, when the diplomat and explorer Pêro da Covilhã went to the Persian Gulf twice to gather intelligence about the Asian commercial world.[1]

Only the southern edges of the Iranian world are mentioned in Portuguese texts up until 1507. This included the Persian Gulf and the Hormuz Island, which they had considered an important trading place since 1500. Relations between Portugal and Iran emerged from Portuguese activity in the Persian Gulf. The Portuguese presence provoked conflicting opinions among Iranian officials up to 1750, ranging from collaboration to antagonism.[1]

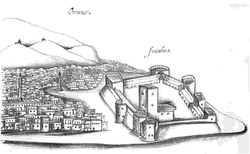

In 1507, the Portuguese conquered Hormuz, which was controlled by Seyf al-Din Aba Nazar, who had recently become a vassal of Shah Ismail I. Afonso de Albuquerque, who had led the conquest, was visited in Hormuz by Iranian officials from Shiraz. They had come to collect the moqarrariya, a tribute paid by Hormuz to its surrounding realms to enable the movement of its goods, which let them trade without taxes up to an amount determined by their role or relevance. Hormuz was lost by Albuquerque in 1508, but he reconquered it in 1515, putting the island under Portuguese "protectorate". This would last until 1622, and caused a conflict with Iran, which viewed Hormuz as a vassal state.[1]

Views and exchanges

[edit]

Throughout 250 years, politics was the most important aspect of Iran–Portugal relations, even though they rarely had the same objectives at the same time, and even less frequently achieved them.[1] Because Persian was widely used in commerce across the Indian Ocean, languages mixed through contact. The Portuguese adopted some Persian words, such as "xabandar" (shāhbandar, port official), or "sodagar" (sowdāgar, merchant). In India, Persian was used by the Portuguese in diplomatic affairs until the 19th century. Persian-speaking personnel were hired by the Portuguese authorities in Iran and India for this purpose, but eventually natives, primarily Indians and some Armenians, were given all these roles. As a result, India was the primary source of Persian loanwords into Portuguese, an exchange that continued until the 20th century. Meanwhile, the Portuguese had less of an impact on Iranian culture, and probably fifteen Portuguese loanwords have been adapted into Persian.[1]

Interest in European art and technology developed slowly in Safavid Iran, unlike in Mughal India. European influence on Persian painting was already noticeable in the mid 16th century, but it only emerged as a distinct style (Farangi-Sazi) in c. 1650, in which the Portuguese played no part. Portugal received textiles, carpets, ceramics, tiles, and other items from Iran, but it had less to do with exchanges of culture and more to do with commercial and consumer practices.[1]

Because there was very little direct trade with Iranians outside of Hormuz, and Portuguese traders made up only a small minority there, the Portuguese likely had fewer encounters with Iranians than the Dutch and the English. As a result, Portuguese interest in and knowledge of Iran and its culture was inaccurate, lacking depth and clouded by religious bias, similar to how they were viewed by the Iranians.[2] The Portuguese are rarely mentioned in Safavid-era chronicles, and when they are, it is usually in a negative context. The Iranians saw them as sea robbers who lived near the coast, a typical Asian view of Portugal. The Portuguese would also be portrayed as "infidel Franks" by Muslim Safavid authors.[1] Western Europeans were rarely mentioned in Safavid-era texts. There is little mention of Europe (Farangestan) as a competitor, threat, or point of comparison, even long after the Safavid dynasty. European figures appear in Safavid-era texts almost exclusively through brief mentions of Portuguese diplomats visiting the shah. Secondary sources, typically from Europe, provide the majority of the information regarding Safavid views on Europeans.[3]

There were many inconsistencies in the Iranian viewpoint of Western Europeans, including the Portuguese. While the Safavid elite distrusted the Portuguese, they were nevertheless intrigued by their ships, weapons, techniques and people. Shah Ismail I (r. 1501–1524) laughed when one of his Qizilbash officers wearing a European cuirass fell, whereas Iskandar Beg Munshi praised the fortifications in Hormuz as a unique display of Western expertise. Western clothing caught the attention of Shah Ismail I's court, and one of his men, claimed to be a Frank while dressed in Portuguese clothing. During the reign of Shah Abbas I (r. 1587–1629), the Portuguese were portrayed in miniatures created by the renowned Iranian artist Reza Abbasi and his students, demonstrating the interest of the Safavid elite towards foreigners.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Teles e Cunha 2009.

- ^ Floor 2021, p. 283.

- ^ Matthee 2021, p. 86.

Sources

[edit]- Floor, Willem (2021). "Commercial Relations between Safavid Persia and Western Europe". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran. Vol. 10. I.B. Tauris. pp. 267–290.

- Matthee, Rudi (2021). "The idea of Iran in the Safavid period: Dynastic pre-eminence and Urban Pride". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran. Vol. 10. I.B. Tauris. pp. 81–105.

- Teles e Cunha, Joao (2009). "Portugal i. Relations with Persia in the Early Modern Age (1500-1750)". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. ISBN 978-0933273955.