Omul

| Omul | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Omul (freshly caught above, smoked below) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Coregonus |

| Species: | C. migratorius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Coregonus migratorius (Georgi, 1775)

| |

| |

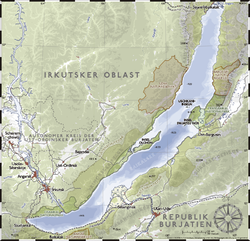

| Lake Baikal, the only home of the omul | |

The omul, Coregonus migratorius, also known as Baikal omul (Russian: байкальский омуль), is a whitefish species of the salmon family endemic to Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia. It is considered a delicacy and is the object of one of the largest commercial fisheries on Lake Baikal.

The omul originated from Arctic whitefish that entered Lake Baikal via river systems roughly 20,000 years ago during the last glaciation. Adaptation to local conditions led to several ecological and morphological forms. Three main groups are recognized: the Pelagic omul, coastal omul, and benthic deepwater omul. The pelagic omul inhabits open water, spawns mainly in the Selenga River, and undertakes the longest migrations.[1] The Coastal-pelagic Omul are common in North Baikal, feeding in nearshore waters and ascending to surface layers at night. The Benthic-deepwater Omul are associated with small-river populations and found in deeper slope habitats.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]The omul has traditionally been regarded as a subspecies of the Arctic cisco Coregonus autumnalis. However, recent genetic studies have shown it actually belongs to the circumpolar Coregonus lavaretus-clupeaformis complex of lake whitefishes, which also has other members in Lake Baikal,[3] and it is now considered its own species within Coregonus.[4] The four or five traditionally accepted subpopulations of omul within Lake Baikal are: North Baikal (северобайкальский), Selenga (селенгинский), Chivyrkui (чивыркуйский) and Posolsk (посольский). These vary in size, feeding behaviors and preferred spawning habitats. The extent of their reproductive isolation is debated.

Description

[edit]The omul is a slender, pelagic fish with light silver sides and a darker back. It has small spots on its dorsal fin and larger ones on its head, a terminal mouth position and a large number of gill rakers, typical of fish that feed in the pelagic zone.[3] The mean size of adults is 36–38 cm and 0.6 to 0.8 kg, though the maximum reported length is 56 cm[4] weighing about 2.5 kg. The subpopulations on the northern end of the lake tend to be smaller.

Behavior

[edit]The omul feeds primarily on zooplankton, smaller fish, and occasionally some benthic organisms. It feeds primarily in the rich pelagic zone of Lake Baikal up to 345–450 m. It is a relatively long-lived, iteroparous species that attains reproductive maturity at five to 15 years of age. The omul only enters the rivers that feed Lake Baikal to spawn, like the Selenga, initiating short spawning migrations, usually in mid-October, broadcasting 8000–30000 eggs before returning to the lake.

Based on Hydroacoustic observations, Omul exhibits three distinct behavioral strategies during the winter that reflect feeding activity and energy conservation. The energy conservation strategy observed in Omul involves resting at depths greater than 200 meters, where the fish remain largely inactive. The feeding activity strategies involve Vertical migrations and schooling behavior with horizontal migrations and active foraging for aggregated food sources.[5]

Diet

[edit]The omul's main food source is an endemic species of alga, Melosira.[6]

Distribution

[edit]Omul is endemic to Lake Baikal, where it occupies a wide range of depths throughout the year. The largest population spawns in the Selenga River, while smaller populations occur in the Upper Angara, Kichera, and numerous small tributaries of Lake Baikal.[7] During the winter and early spring periods, the species is primarily distributed along the slope zones of the lake, particularly in areas adjacent to the deltas and estuaries of spawning rivers. Hydroacoustic observations conducted from the winter distribution have shown that omul are found at depths of 50 to 350 meters. In early winter, gillnet surveys recorded dense aggregations between 150 and 300 meters, whereas in late winter occasional dense schools were observed at 50-100 meters, likely associated with feeding activity.[5]

In the spring, Omul maintains a similar depth range but exhibits a two-layer vertical distribution, with one group occupying the 50-150 meter layer and another occurring between 160 and 350 meters. The open central basin of the lake, where depths exceed 400 meters, contains far fewer fish compared to the nearshore fishing zones.[5]

Life History

[edit]Spawning behavior

[edit]The omul spawns exclusively in rivers feeding Lake Baikal, primarily the Selenga, Upper Angara, and Barguzin. There are 22 identified spawning rivers, with the Selenga alone containing nearly half of all spawning grounds. Spawning migrations begin in early September and extend through October, with omul traveling up to 580 km upstream in the Selenga. Females cease feeding about a week before entering rivers and complete gonadal maturation during migration. Early-migrating shoals reach more distant sites, while later groups spawn closer to river mouths. Migration speed increases with river length and latitude, ranging from about 1 km per day in southern tributaries to over 10 km per day in northern ones.[8]

Reproductive Biology and Fecundity

[edit]A study on the reproductive guild of Baikal Omul in the Posolskiy Sor Bay found increases in average weight, length, body height, and absolute individual fecundity (AIF) in bottom-deep-sea spawning populations. This research was conducted in the following years after the 2017/2018 fishing ban. The authors noted apparent increases in growth rates and fecundity, which were associated with a decrease in anthropogenic impact. The data shows that younger individuals of Baikal Omul, ages 9-11+ years exhibited higher growth rates in both weight and length compared to older age groups. In both 2019 and 2020, fish aged 9+ years had the greatest weight and length gains, while growth decreased progressively with age. The relative length and height of fins also decreased with age in both sexes, except for the anal and pelvic fins in males. The study additionally noted the presence of epithelial tubercles on the lateral scales, which are characteristic of mature individuals during the spawning period.[9]

The increase in absolute individual fecundity (AIF), the total number of eggs produced by a single female fish during one spawning season, was considered to have an adaptive value, contributing to the recovery of the Baikal Omul population. In 2019, the average AIF was reported at 18,572 eggs, increasing to 19903 ± 549 in 2020. Statistical analysis confirmed a significant relationship between age and fecundity (F = 4.16 > Fcritical = 2.56, P = 0.006). Older individuals 11-12+ years produced approximately 4,475 more eggs than younger fish 9+ years, indicating that fecundity rises with age. However, relative individual fecundity (eggs per gram of body weight) decreased with age, from 33.83 units/g (8+) to 27.81 units/g (12+). A comparison of 2019 and 2020 data also showed slightly higher relative fecundity in 2020 most age classes, suggesting improved reproductive conditions following the fishing ban.[9]

Egg Incubation and Spawning Habitat

[edit]Substrate

[edit]Baikal Omul spawn predominantly on hard substrates composed of gravel, pebbles, cobbles, and coarse sand. The highest egg densities occur on gravel-cobble substrates. Eggs are rarely deposited on soft materials (silt or fine sand), where mortality is significantly higher.[10]

Depth

[edit]Eggs are typically found at depths of 1.5-6 m. Shallower areas are avoided because winter water levels drop, increasing the risk of freezing or desiccation.[10]

Water Velocity

[edit]Eggs occur at 0.05-0.7 m/s, with maximum densities at 0.1 m/s. Very slow flows promote silt deposition, while strong currents (>0.7 m/s) can dislodge eggs.[10]

Incubation

[edit]Incubation lasts 180-200 days under ice at approximately 0°C. Eggs overwinter from November to April and hatch in April-May.[10]

Conservation Status

[edit]Threats

[edit]As of 2025 the Conservation Outlook has assessed Lake Baikal as “Significant concern - The site’s values are threatened and/or are showing signs of deterioration. Significant additional conservation measures are needed to maintain and/or restore values over the medium to long-term.” Key threats to the lake’s ecosystem are pollution, overfishing, poor sewage treatment leading to nearshore eutrophication, and climate change.[11]

Pollution

[edit]Water pollution in Lake Baikal has worsened due to inadequate wastewater treatment, industrial discharge, and increased tourism activity. The presence of chemical substances such as phosphates, commonly used in detergents and fertilizers, contributes to eutrophication, a body of water over enriched with nutrients, and the growth of harmful algal blooms. Phthalates, synthetic chemicals used in plastics and personal care products, have also been detected in the lake and may act as pollutants that disrupt aquatic ecosystems. Historical industrial activity, including operations of the Baikalsk Pulp and Paper Mill, contributed to long-term pollution of Lake Baikal through the release of chemical waste and untreated wastewater. Although such facilities have since been closed, residual contamination in sediments and surrounding waters continues to affect the lake’s ecosystem and may have lasting impact on species such as the Baikal omul. These factors degrade water quality and can negatively affect the spawning and feeding habitats of the Baikal omul.[11]

Overfishing

[edit]Overfishing in previous decades caused a sharp decline in Baikal omul (Coregonus migratorius) populations. Although a 2018 ban on commercial fishing appears to have stabilized this trend, numbers remain well below historical levels and continue to fluctuate. Ongoing threats include unfavorable climatic and ecological conditions for reproduction, water pollution, habitat alterations linked to the Irkutsk hydropower plant, and potential pressure from natural predators such as Baikal seals and cormorants.[11]

Conservation Efforts

[edit]In an effort to restore fish populations, the Russian government allocated Rub800 million (US$12 million) to enhance three hatcheries in the Republic of Buryatia near Lake Baikal. In 2019 the state-owned hatcheries released 450 million units of fry into the lake - highest number released in prior years. The three hatcheries; Bolsherechensky, Selengvinsky, and Husinoozersky, were mandated to grow 1.5 million fingerlings of Omul (Coregonus migratorius) and 1.5 million units of sturgeon (Acipenseridae).[12]

Consumption and fishery

[edit]Omul is one of the primary food resources for people living in the Baikal region. It is considered a delicacy throughout Russia, and export to the west is of some economic importance. Smoked omul is widely sold around the lake and is one of the highlights for many travelers on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and locals tend to prefer the fish salted. A popular Siberian salad called stroganina consists of uncooked frozen omul shaved thinly and served with pepper, salt and onion.

Omul is also used in a dish called saguaday which is a salad made of raw omul with salt, pepper, and oil. Another common preparation involves freshly caught omul: the fish is carefully washed, salted, and pierced along its ridge with a wooden stick. The piercing must be gentle, in order not to damage the gallbladder. The skewered omul is then roasted and served with scallions or rice.[13]

Due to its high demand, the omul is the object of one of the most important commercial fisheries in Lake Baikal. The highest recorded annual landed catches occurred in 1940s and amounted to 60-80 thousand tonnes.[14] A subsequent crash in the population led to a closing of the fishery in 1969, followed by a reopening with strict quotas in 1974 after some recovery of the stocks.[15] Currently, the omul fishery accounts for roughly two-thirds of the total Lake Baikal fishery.[16] Fluctuations in the population and intensive fishing make sustaining the fishery one of the highest priorities for local fisheries managers.

In 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation banned commercial amateur, and sport fishing of Baikal omul to prevent further stock depletion. In an effort to address overfishing while exploring sustainable commercial practices, a study was conducted that investigated the mathematical modeling of Baikal omul populations. The model describes how the population changes depending on whether natural growth or fishing pressure is greater. The researchers used this framework to identify conditions that would allow sustainable fishing while avoiding population collapse, and to evaluate potential long-term management strategies for conserving omul in Lake Baikal.[7]

Gallery

[edit]-

Freshly caught Baikal omul

-

Baikal omul

-

Baikal cold-smoked omul on the counter of the store

-

Omul on a cutting board

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bychenko, O.S.; Sukhanova, L.V.; Azhikina, T.L.; Sverdlov, E.D. (2012-04-02). "Search for genetic bases of species differences between Lake Baikal coregonid fishes: whitefish, C. baicalensis, and omul, C. migratorius". Advances in Limnology. 63: 177–186. doi:10.1127/advlim/63/2012/177. ISSN 1612-166X.

- ^ Smirnov, Vasily V. (2012). "Fishery Management of Omul (Coregonus Autumnalis Migratorius) as Part of the Conservation of Ichthyofauna Diversity in Lake Baikal". Polish Journal of Natural Sciences. 27 (2): 203–214.

- ^ a b Sukhanova, L.V.; et al. (2004). "Grouping of Baikal Omul Coregonus autumnalis migratorius Georgi within the C. lavaretus complex confirmed by using a nuclear DNA marker" (PDF). Ann. Zool. Fenn. 41: 41–49.

- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Coregonus migratorius". FishBase. January 2008 version.

- ^ a b c Anoshko, P. N.; Makarov, M. M.; Smolin, I. N.; Dzyuba, E. V. (2019-08-22). "The results of the first hydroacoustic studies of the winter distribution of Coregonus migratorius in Lake Baikal". Limnology and Freshwater Biology (3): 232–235. doi:10.31951/2658-3518-2019-A-3-232. ISSN 2658-3518.

- ^ Planet, Lonely; Richmond, Simon; Baker, Mark; Butler, Stuart; Holden, Trent; Karlin, Adam; Kohn, Michael; Masters, Tom; Ragozin, Leonid; Louis, Regis St (April 1, 2018). Lonely Planet Trans-Siberian Railway. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-78701-957-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Sorokina, P.; Baikal State University, Lenin Str., 11, Irkutsk, 664003, Russia; Limnological Institute, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Ulan-Batorskaya Str., 3, Irkutsk, 664033, Russia (2020). "Mathematical modelling of population dynamics of Baikal omul under commercial catch". Limnology and Freshwater Biology (4): 750–751. doi:10.31951/2658-3518-2020-A-4-750 (inactive 15 November 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2025 (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Voronov, M G; Bolshunova, E A; Luzbaev, K V (2021-02-01). "Spawning Migrations of the Baikal Omul". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 670 (1): 012017. Bibcode:2021E&ES..670a2017V. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/670/1/012017. ISSN 1755-1307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ a b Shatalin, Vladislav; Moruzi, Irina; Rostovtsev, Aleksandr; Kozhemyakin, Kirill; Tkachev, Valentin (2022). "Some biological characteristics of the reproductive gild of Baikal omul, Coregonus migratorius (Georgi, 1775) in the Posolskiy Sor Bay". Iranian Journal of Ichthyology. 9 (3): 140–148 – via Iranian Society of Ichthyology.

- ^ a b c d Bazova, N V; Bazov, A V (2021-11-01). "Influence of abiotic factors on incubation of Baikal omul eggs in the Selenga River (Lake Baikal Basin)". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 908 (1): 012013. Bibcode:2021E&ES..908a2013B. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/908/1/012013. ISSN 1755-1307.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ a b c "Lake Baikal | World Heritage Outlook". worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Retrieved 2025-11-15.

- ^ "Russia spends US$12M to help restore fish populations - Hatchery InternationalHatchery International". 2019-09-13. Retrieved 2025-11-15.

- ^ "Baikal Lake Omul - Arca del Gusto". Slow Food Foundation. Retrieved 2025-11-15.

- ^ "REC Baikal". lake.baikal.ru.

- ^ Galazin, G.I. (1978) Рыбные ресурсы Байкала и их использование (Fish resources of Baikal and their exploitation). Problemy Baikala, Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, v. 16 (36). (in Russian) [1]

- ^ Ye.I. Buyanova (2002) Экология рыбного хозяйства бассейна озера Байкал (Ecology of commercial fisheries on Lake Baikal), MSU, Moscow, 2002. (in Russian) [2] Archived 2007-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit] Media related to Coregonus migratorius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coregonus migratorius at Wikimedia Commons