Northern line

| Northern line | |

|---|---|

1995 Stock arrives at Stockwell tube station heading northbound to Edgware via Bank, July 2024 | |

| Overview | |

| Termini |

|

| Stations | 52 |

| Colour on map | Black |

| Website | tfl |

| Service | |

| Type | Rapid transit |

| System | London Underground |

| Depot(s) |

|

| Rolling stock | 1995 Stock |

| Ridership | 339.7 million passenger journeys (2019)[2] |

| History | |

| Opened |

|

| Last extension | 20 September 2021 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 58 km (36 mi) |

| Character | Deep-tube |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Fourth rail, 630 V DC |

| Operating speed | 45 mph (72 km/h)[3] |

| Signalling | CBTC (SelTrac) |

The Northern line is a London Underground line that runs between North London and South London. It is printed in black on the Tube map. It carries more passengers per year than any other Underground line – around 340 million in 2019 – making it the busiest tube line in London. The Northern line is unique on the network in having two routes through Central London, two northern branches and two southern branches. Despite its name, it does not serve the northernmost stations on the Underground, though it does serve the southernmost station at Morden, the terminus of one of the two southern branches.

The line's northern termini, all in the London Borough of Barnet, are at Edgware and High Barnet; Mill Hill East is the terminus of a single-station branch line off the High Barnet branch. The two main northern branches run south to join at Camden Town where two routes, one via Charing Cross in the West End and the other via Bank in the City, continue and then join at Kennington in Southwark. At Kennington the line again divides into two branches, one to each of the southern termini – at Morden, in the borough of Merton, and at Battersea Power Station in Wandsworth.

For most of its length the Northern line is a deep tube line.[a] The portion between Stockwell and Borough opened in 1890 and is the oldest section of deep-level tube line on the network. Nearly 340 million passenger journeys were recorded in 2019 on the Northern line, making it the busiest on the Underground, although this is distorted due to having two branches within Central London, both of which are less busy than the core sections of other lines.[4] Despite the line's name, it has 18 of the system's 31 stations south of the River Thames. There are 52 stations in total on the line, of which 38 have platforms below ground.

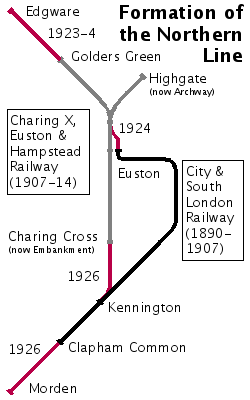

The line's structure of two northern branches (one with a further short branch), two central branches, and two southern branches reflects its complicated history. The core of the line, including the two central branches and the beginnings of the two northern branches, was constructed by two companies, the City and South London Railway and the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway, in the 1890s and 1900s. The companies came under the same ownership in 1913, and were physically connected and operationally merged in the 1920s, while at the same time extensions to Edgware and Morden were completed. In the 1930s and 1940s the Northern line took over and electrified the London and North Eastern Railway branches to Mill Hill East and High Barnet. This was the final extension of the line for eight decades, though between the 1930s and 1970s the Northern City Line was branded and operated as part of the Northern line despite being disconnected from the rest of the line. The most recent extension, a second southern branch from Kennington to Battersea, opened on 20 September 2021. There are proposals to split the line into two lines.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2019) |

Formation

[edit]

The core of the Northern line evolved from two railway companies: the City & South London Railway (C&SLR) and the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR).

The C&SLR was London's first electric hauled deep-level tube railway. It was built under the supervision of James Henry Greathead, who had been responsible for the Tower Subway.[5] It was the first of the Underground's lines to be constructed by boring deep below the surface and the first to be operated by electric traction.[6] The railway opened in November 1890 from Stockwell to a now-disused station at King William Street.[7] This was inconveniently placed and unable to cope with the company's traffic so in 1900 a new route to Moorgate via Bank was opened.[8] By 1907, the C&SLR had been further extended at both ends to run from Clapham Common to Euston.[9]

The CCE&HR, commonly known as the "Hampstead Tube", was opened in 1907 and ran from Strand (nowadays Charing Cross) via Euston to Camden Town with branches splitting to Golders Green and Highgate (nowadays Archway).[10][11] It was extended south by one stop to Charing Cross (nowadays Embankment) in 1914 to form an interchange with the Bakerloo and District lines.[11][12] In 1913, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), owner of the CCE&HR, took over the C&SLR although they remained separate companies for some time.[13]

Integration

[edit]During the early 1920s a series of works were carried out to connect the C&SLR and CCE&HR tunnels to enable an integrated service to be operated. The first of these new tunnels between the C&SLR's Euston and CCE&HR's Camden Town stations had originally been planned in 1912 but was delayed by the First World War.[14][15] Construction began in 1922 and this first tunnel opened in 1924.[11][15] The second connection linking the CCE&HR's Embankment and C&SLR's Kennington stations opened in 1926.[11][15] It provided a new intermediate station at Waterloo to connect to the main line station. The smaller diameter tunnels of the C&SLR were also enlarged to match the standard diameter of the CCE&HR and other deep tube lines.[16] In conjunction with the works to integrate the two lines, two major extensions were undertaken: northwards to Edgware in Middlesex and southwards to Morden in Surrey.

The Edgware extension used plans dating back to 1901 for the Edgware and Hampstead Railway[17] which the UERL's subsidiary, the London Electric Railway, had taken over in 1912.[18] It extended the CCE&HR line from its terminus at Golders Green to Hendon Central in 1923 and to Edgware in 1924.[11][19] The line crossed open countryside and ran mostly on viaduct from Golders Green to Brent and then on the surface, apart from a short tunnel north of Hendon Central.[19] Five new stations were built to pavilion-style designs by Stanley Heaps, stimulating the rapid northward expansion of suburban developments in the following years.[20]

The engineering of the Morden extension of the C&SLR from Clapham Common to Morden was more demanding, running in tunnel to Morden station which was then constructed in a cutting and the line continued a bit beyond to the depot. The extension was initially planned to continue to Sutton[21] over part of the route of the unbuilt Wimbledon and Sutton Railway (in which the UERL held a stake) but agreements were made with Southern Railway (SR) to end the extension at Morden, the SR building a surface line from Wimbledon to Sutton in the 1930s via South Merton and St. Helier.[b] The tube extension itself opened in 1926 with seven new stations all designed by Charles Holden in a modern style.

Owing to the complicated nature of the resulting line, it became known as the Morden–Edgware line, although a number of alternative portmanteau names were mooted in the fashion of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway becoming the Bakerloo line, such as "Edgmor", "Mordenware", "Medgeway" and "Edgmorden" lines.[22]

After the UERL and the Metropolitan Railway (MR) became unified under the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) in 1933, the MR's Great Northern & City Railway subsidiary, which ran mostly underground from Moorgate to Finsbury Park, transferred management to the Morden–Edgware line, branding itself as the Northern City line.

Northern Heights plan

[edit]

Following the formation of the LPTB, in June 1935 the organisation proposed the New Works Programme, an ambitious plan to expand the Underground network in response to London's growing suburban population and relieve congestion on the existing steam-operated suburban lines. In the case of the Morden–Edgware, these were the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) suburban lines north of Highgate, built in the 1860s and 1870s by the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway (EH&LR) and its successors, running from Finsbury Park to Edgware via Highgate, with branches to Alexandra Palace and High Barnet.

The Morden–Edgware line's project, known as the Northern Heights plan owing to the high ground in north London,[23] involved fourth-rail electrification of the surface lines and the double-tracking of the single-line section between Finchley (Church End) and Edgware. The Northern Heights plan also called for the construction of three new linking sections of track: between the Northern City line and new surface level platforms at Finsbury Park; a deep-level tunnel from Archway to East Finchley; and a diversion of the Mill Hill branch to the LPTB's Edgware station.[24]

In addition, the Edgware branch would also be extended beyond the terminus to a site at Bushey Heath, the LPTB having retained planning rights of the unbuilt Watford and Edgware Railway, which had long intended an extension of the EH&LR's Edgware branch towards Watford. A new depot at Aldenham, just before the Bushey Heath terminus, would also be constructed to facilitate the housing of additional trains.[25] As a result of the project's name, the Morden–Edgware line was renamed as the Northern line.[26][27][28]

Work began on the initial stages of the extensions in 1936, as did that on Bushey Heath following its authorisation in 1937, with completion projected by 1941.[24] The tunnelling northwards from Archway was the first element to be completed and an initial service to the rebuilt East Finchley station commenced on 3 July 1939, though trains skipped the deep-level platforms at Highgate until its fitout was completed by 19 January 1941.

Further progress was disrupted by the start of the Second World War in September 1939; however enough development had been made to complete the electrification of the High Barnet branch, over which tube services started on 14 April 1940, and the single-track LNER line to Edgware being electrified as far as Mill Hill East, reopening as a tube service on 18 May 1941 to serve the nearby Inglis Barracks. The partially-complete depot at Aldenham was converted into an aircraft factory, constructing Handley Page Halifax bombers as part of the war effort.[25][29] Other work on the extension that were eventually halted during the Second World War included the construction of a viaduct at Brockley Hill and a tunnel near Elstree South which started in June 1939, the laying of a second line as far as Mill Hill (The Hale) and the construction of its second platform.[30]

After the war, much of the area beyond Edgware was made part of the Metropolitan Green Belt that largely prevented the anticipated residential development, thus the potential demand for services from Bushey Heath vanished.[25] A compromise was offered to make Brockley Hill the line's terminus and retain a link to Aldenham Depot,[24] but the Bushey Heath extension was cancelled in 1950.[31] Although efforts were made to complete Aldenham Depot as an Underground facility, from December 1947 it was modified for use as a heavy repair works of bus bodies, supposedly temporarily until Aldenham was required for railway purposes. Following the extension's cancellation, the depot was converted into an overhaul facility for buses, serving this purpose until 1986.[32]

The introduction of electric services to High Barnet and Mill Hill East undermined passenger numbers on the remaining LNER-operated lines. Consequently, passenger services to Mill Hill (The Hale) and Edgware, having been suspended in September 1939 to allow works to be completed, never resumed[30] and the Alexandra Palace branch line via the surface platforms at Highgate ceased to passenger traffic on 3 July 1954, with the last of the Northern Heights plans also being dropped that year.[24] Available funds were directed towards completing the eastern extension of the Central line instead. Freight-hauled mainline trains continued to run alongside Northern line services until 1964.[33] Tickets were still being sold to and from Mill Hill (The Hale) until the late 1960s, with passengers being directed onto the 240 bus to connect with the Underground.[30]

The connection between Drayton Park and the surface platforms at Finsbury Park, which gave access onto the Finsbury Park–Highgate line, was retained for rolling stock transfers between the Northern City and Northern line until 1970, the incomplete electrification on this section necessitating stock being hauled by battery-electric locomotives.[24] Passenger services commenced on the Finsbury Park link in 1976, when the Northern City line transferred to British Rail ownership.

Recent developments

[edit]

In a separate proposal to the New Works Programme, the LPTB looked into extending the Northern line south of Morden to North Cheam as late as 1944 alongside a relief line from Kennington to Epsom via Morden.[34] Further proposals included building additional tunnels between Kennington and Tooting Broadway to relieve congestion, with alternative duplication suggested between Golders Green and Waterloo.[35] In the 1980s, an extension of the Northern line to Peckham Rye and Streatham Hill was proposed as part of a review of potential extensions of Underground lines.[36]

Between 1989 and 1992, Angel tube station was rebuilt with a new northbound tunnel alongside the existing station platforms which were widened to become the new southbound platform, replacing the old narrow platforms which by then had become a safety hazard with increased passenger ridership.[37] A similar project was undertaken at Euston in the 1960s in conjunction with the construction of the Victoria line[37] and at Bank in the early 2020s in order to increase station capacity and improve accessibility.[38][39]

By the early 1990s, the line had deteriorated due to years of under-investment and the use of old rolling stock, most of which dated back to the early 1960s.[40] The line gained the nickname "Misery Line" due to its perceived unreliability.[41][42] In 1995, a comprehensive refurbishment of the line began – including track replacement, power upgrades, station modernisation (such as Mornington Crescent) and the replacement of older rolling stock with new 1995 Stock thanks to a public–private partnership deal with Alstom.[43][44]

The Northern line was originally scheduled to switch to automatic train operation in 2012, using the same SelTrac S40 system[45] as used since 2009 on the Jubilee line and for a number of years on the Docklands Light Railway.[46] Originally the work was to follow on from the Jubilee line so as to benefit from the experience of installing it there, but that project was not completed until spring 2011. Work on the Northern line was contracted to be completed before the 2012 Olympics. It was then undertaken in-house, and TfL predicted the upgrade would be complete by the end of 2014.[47] The first section of the line (West Finchley to High Barnet) was transferred to the new signalling system on 26 February 2013[48] and the line became fully automated on 1 June 2014, with the Chalk Farm to Edgware via Golders Green section being the last part of the line to switch to ATO.[49][50]

Since the mid-autumn of 2016,[51] a 24-hour "Night Tube" service has run on Friday and Saturday nights from Edgware and High Barnet to Morden via the Charing Cross branch; service is suspended on the Bank branch during these times.[52] Trains run every eight minutes between Morden and Camden Town and up to every 16 minutes on the Edgware and High Barnet branches. Labour disputes delayed the planned start date of September 2015.[53]

In January 2018, Transport for London announced that it would double the period during which it runs peak evening services in the central London section to tackle overcrowding. There would now be 24 trains per hour on both central London branches and the northern branches, as well as 30 trains per hour on the Kennington to Morden section between 5 pm and 7 pm.[4]

Battersea extension

[edit]Throughout the 2000s, no plans were considered for extending the Northern line, as the PPP contracts to upgrade the Underground did not include provision for line extensions.[54][55] This prolonged period without an extension ultimately changed when the Northern line was extended to serve the redevelopment of Battersea Power Station in 2021. Partially funded by private developers, the £1.2bn project extended the Charing Cross branch of the line for 3.2 km (2.0 miles) from Kennington to Battersea Power Station,[56] with an intermediate stop at Nine Elms.[57][58] Approved by Wandsworth Council in 2010[59] and TfL in 2014,[57] construction began in 2015. Tunnelling for the project was completed in 2017,[56] and the extension opened on 20 September 2021.[60][61] Provision has been made for a future extension to Clapham Junction.[62]

Services

[edit]Peak

[edit]As of September 2021, morning peak southbound services are:[63]

- 4 tph from Edgware to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 2 tph from Edgware to Morden via Charing Cross

- 12 tph from Edgware to Morden via Bank

- 10 tph from High Barnet to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 2 tph from High Barnet to Morden via Charing Cross

- 8 tph from High Barnet to Morden via Bank

- 2 tph from Mill Hill East to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 2 tph from Mill Hill East to Morden via Bank

This service pattern provides 20 tph between Finchley Central and High Barnet, 4 tph between Finchley Central and Mill Hill East, 16 tph between Kennington and Battersea Power Station and 22 tph everywhere else on the line except between Kennington and Morden, between Camden Town and Finchley Central and on the Edgware branch where there are 24 tph.

Off-peak

[edit]As of November 2022, off-peak services are the similar to peak services, minus the four hourly trains that run from Morden to the northern branches via Charing Cross:[63]

- 10 tph from Edgware to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 10 tph from Edgware to Morden via Bank

- 8 tph from High Barnet to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 8 tph from High Barnet to Morden via Bank

- 2 tph from Mill Hill East to Battersea Power Station via Charing Cross

- 2 tph from Mill Hill East to Morden via Bank

This service pattern provides 16 tph between Finchley Central and High Barnet, 4 tph between Finchley Central and Mill Hill East, and 20 tph everywhere else on the line.

Night

[edit]Since 2016, the Northern line has operated Night Tube services on Friday and Saturday nights between the Edgware and High Barnet termini and Morden via the Charing Cross branch only. Trains run every 15 minutes on each of the northern branches, combining to give eight trains per hour between Camden Town and Morden. There is no Night Tube service on the Mill Hill East, Bank or Battersea branches.[51]

- 4 tph from High Barnet to Morden via Charing Cross

- 4 tph from Edgware to Morden via Charing Cross

Map

[edit]

Stations

[edit]Northern line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Open stations

[edit]High Barnet branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Branch | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Barnet |

|

1 April 1872 | High Barnet branch | Terminus. Northern line introduced 14 April 1940map 1 |

| Totteridge & Whetstone |  |

Northern line introduced 14 April 1940 map 2 | ||

| Woodside Park |

|

Northern line introduced 14 April 1940map 3 | ||

| West Finchley |

|

1 March 1933 | Northern line introduced 14 April 1940map 4 | |

| Mill Hill East |

|

22 August 1867 | Mill Hill branch | Closed 11 September 1939, reopened 18 May 1941map 5 |

| Finchley Central |

|

High Barnet & Mill Hill branches | First Northern line train was 14 April 1940map 6 | |

| East Finchley |  |

High Barnet branch | First Northern line train was 3 July 1939map 7 | |

| Highgate |  |

19 January 1941 | Disused surface station opened 22 August 1867map 8 | |

| Archway |  |

22 June 1907 | Originally named Highgatemap 9 | |

| Tufnell Park |  |

map 10 | ||

| Kentish Town |

|

Mainline station opened 13 July 1868. Change for National Rail services.map 11 |

Edgware branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edgware |

|

18 August 1924 | Terminusmap 12 |

| Burnt Oak |  |

27 October 1924 | Opened with its current name, then renamed as "Burnt Oak (Watling)" approximately four years after its opening; was reverted to its original name in 1950.map 13 |

| Colindale |  |

18 August 1924 | Used as a terminus for some trains travelling north.map 14 |

| Hendon Central |

|

19 November 1923 | map 15 |

| Brent Cross |  |

Opened as "Brent"; renamed 20 July 1976.map 16 | |

| Golders Green |

|

22 June 1907 | Originally a terminus; remains a terminus for some trains.map 17 |

| Hampstead |  |

Originally proposed to be named "Heath Street"; this name can still be seen on wall tilings on station platform walls.map 18 | |

| Belsize Park |  |

One of eight London Underground stations that have deep-level air-raid shelters underneath them. The shelter was constructed in the Second World War to provide safe accommodation for service personnel.map 19 | |

| Chalk Farm |  |

map 20 |

Camden Town

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Branch | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden Town |  |

22 June 1907 | Edgware, High Barnet, Charing Cross and Bank branches[c] | The junctions connecting the two northern branches of the Northern line to the two central branches are just south of Camden Town station. The station has a pair of platforms on each of the two northern branches, and southbound trains can depart toward either Charing Cross or Bank from either of the two southbound platforms without crossing over.map 21 |

Charing Cross branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mornington Crescent |  |

22 June 1907 | Was planned to be named "Seymour Street", but this was changed. It was closed on 23 October 1992 to replace the lifts and was reopened on 27 April 1998.map 22 |

| Euston (Charing Cross branch) |

|

Change for southbound Northern line service via Bank from platform 6, Victoria line, Lioness line and National Rail servicesmap 23 | |

| Warren Street |  |

Change for Victoria linemap 24 | |

| Goodge Street |  |

Opened as "Tottenham Court Road"; renamed 3 September 1908map 25 | |

| Tottenham Court Road |

|

Change for Central line and Elizabeth line. | |

| Leicester Square |  |

Piccadilly line opened 15 December 1906 map 27 | |

| Charing Cross |

|

Bakerloo line opened as Trafalgar Square 10 March 1906. Stations combined 1 May 1979. Change for Bakerloo line and National Rail servicesmap 28 | |

| Embankment ( |

|

6 April 1914 | District Railway opened 30 May 1870. Northern line extension from Charing Cross opened 6 April 1914. Extension from Kennington opened 13 September 1926. Change for Bakerloo, Circle and District linesmap 29 |

| Waterloo |

|

13 September 1926 | Waterloo and City line opened 8 August 1898. Extension from Kennington opened 13 September 1926. Change for Bakerloo, Jubilee and Waterloo & City lines and National Rail servicesmap 30 |

Bank branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euston (Bank branch) |

|

12 May 1907 | Change for southbound Northern line service via Charing Cross from platform 2, Victoria line, Lioness line and National Rail servicesmap 23 |

| King's Cross St Pancras |

|

Metropolitan Railway station opened 10 January 1863. Change for Circle, Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan, Piccadilly and Victoria lines, National Rail services and Eurostarmap 31 | |

| Angel |  |

17 November 1901 | Has the longest escalator on the entire Underground networkmap 32 |

| Old Street |

|

Northern line platforms opened February 1904. Connects with National Rail services.map 33 | |

| Moorgate |

|

25 February 1900 | Metropolitan Railway station opened 23 December 1865. Change for Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines and National Rail services.map 34 Has an interchange with the Elizabeth line via Liverpool Street station. |

| Bank |

|

Linked with Monument by escalator 18 September 1933, change for Central, Circle, District and Waterloo & City lines and Docklands Light Railway.map 35 | |

| London Bridge |

|

Change for Jubilee line and National Rail servicesmap 36 | |

| Borough |  |

18 December 1890 | map 37 |

| Elephant & Castle |

|

Change for Bakerloo line and National Rail servicesmap 38 |

Kennington

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Branch | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennington |  |

18 December 1890 | Charing Cross, Bank, Battersea and Morden branches[d] | The station has four platforms arranged in two pairs: one pair for northbound services to each central branch of the Northern line, the other pair for southbound services from each central branch. The junctions connecting the central branches to the southern branches are just south of Kennington station. Southbound trains from the Charing Cross branch can terminate at this station, which has a reversing loop, or join either southern branch; southbound trains from the Bank branch can proceed onto the Morden branch but not the Battersea branch.map 39 |

Battersea branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nine Elms |

|

20 September 2021 | |

| Battersea Power Station |

|

Terminus |

Morden branch

[edit]| Station | Image | Opened | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oval |  |

18 December 1890 | map 40 |

| Stockwell |  |

Change for Victoria line. Original terminus until 1900, when the line was extended to Clapham Common. The station platforms were resited south of the original island platform. Formerly a depot existed here; it was branched off from the current southbound track. It is one of the eight stations that have a deep level air-raid shelter. map 41 | |

| Clapham North |  |

3 June 1900 | One of the two remaining stations to have an island platform underground. It is also one of the eight stations that have a deep level air-raid shelter.map 42 |

| Clapham Common |  |

Terminus from 1900 to 1926. It is also one of the two remaining stations to have an island platform underground. It is also one of the eight stations that have a deep level air-raid shelter.map 43 | |

| Clapham South |  |

13 September 1926 | One of the eight stations that have a deep level air-raid shelter.map 44 |

| Balham |

|

6 December 1926 | Change for National Rail servicesmap 45 |

| Tooting Bec |  |

13 September 1926 | Opened as "Trinity Road"; renamed 1 October 1950map 46 |

| Tooting Broadway |  |

Used as a terminus for some trains heading southmap 47 | |

| Colliers Wood |  |

map 48 | |

| South Wimbledon |  |

Opened as "South Wimbledon (Merton)". The suffix gradually fell out of use, but still can be seen on some platform signage.map 49 | |

| Morden |

|

Terminusmap 50 |

Closed stations

[edit]Permanently closed stations

[edit]- King William Street (closed 1900; replaced by Bank)

- City Road (closed 1922)

- South Kentish Town (closed 1924)

- North End (also known as "Bull & Bush". Never opened; work stopped 1906)

Resited stations

[edit]- Stockwell – new platforms resited immediately to the south of its predecessor with the 1922–1924 upgrade of the line.

- London Bridge – the northbound tunnel and platform converted into a concourse, and a new northbound tunnel and platform built in the late 1990s to increase the platform and circulation areas in preparation for the opening of the Jubilee line.

Abandoned plans

[edit]Northern Heights stations not transferred from LNER

[edit]- Highgate – High-level only

- Stroud Green

- Crouch End

- Cranley Gardens

- Muswell Hill

- Alexandra Palace

- Mill Hill (The Hale)

Bushey Extension stations not constructed

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]Rolling stock

[edit]

When the line opened, it was served by 1906 Stock. This was replaced by Standard stock which was in turn replaced by 1938 stock as part of the New Works Programme, later supplemented with identical 1949 Stock. When the Piccadilly line was extended to Heathrow Airport in the 1970s, its 1959 Stock and 1956 Stock (prototypes of the 1959 Stock) trains were transferred to the Northern line. As there were not enough 1956 and 1959 Stock trains to replace the Northern line's 1938 Stock fleet, they were supplemented with newly built 1972 Mark 1 Stock trains, which all served the line at the same time. 1972 Mark 2 stock trains also ran on this line until going to the Jubilee line; they were then moved to the Bakerloo line, where they remain in service. By 1986, increasing unreliability of 1959 stock trains meant there were regularly too few trains to run a full peak service. Five 1938 stock trains, newly retired from the Bakerloo Line, were overhauled and returned to the Northern Line to serve another two years until further 1972 stock could be transferred from the Jubilee Line, which was moving to 1983 stock. The few 1956 Stock trains were briefly replaced by 1962 Stock transferred from the Central line in 1995, before the entire Northern line fleet was replaced with 1995 Stock between 1998 and 2000.

Today, all Northern line trains consist of 1995 Stock in the Underground livery of red, white and blue. In common with the other deep-level lines, the trains are the smaller of the two loading gauges used on the system. 1995 stock has automated announcements and quick-close doors.[citation needed] If the proposed split of the line takes place (initial estimates of 2018 having been abandoned to focus on completion of the Battersea and Nine Elms extension work), 19 new trains will be added to the existing fleet of 106 trains,[64] though additional trains beyond the extra 19 trains may be required to provide a full service for the new Battersea extension.

Tunnels

[edit]Although two other London Underground lines operate fully underground, the Northern line is unusual in that it is a deep-level tube line that serves the outer suburbs of South London yet there is only one station above ground (Morden tube station) while the rest of this part of the line is deep below ground. The short section to Morden depot is also above ground. This is partly because its southern extension into the outer suburbs was not done by taking over an existing surface line as was generally the case with routes such as the Central, Jubilee and Piccadilly lines. Apart from the core central underground tunnels, part of the section between Hendon and Colindale is also underground. As bicycles are not allowed in tunnel sections (even if no station is in that section) as they would hinder evacuation, they are limited to High Barnet – East Finchley, the Mill Hill East branch, Edgware – Colindale and Hendon Central – Golders Green.[65] There are also time-based restrictions for the sections where bicycles are allowed.[65]

The tunnel from Morden to East Finchley via Bank, 17 miles 528 yards (27.841 km),[1] was for a time the longest rail tunnel in the world. Other tunnels, including the Channel Tunnel that links the UK and France, are now longer.

Depots

[edit]The Northern line is serviced by four depots. The main one is at Golders Greenmap 51, adjacent to Golders Green tube station, while the second, at Morden,map 52 is south of Morden tube station and is the larger of the two. The other two are at Edgware and Highgate. The Highgate depot is on the former LNER branch to Alexandra Palace. There was originally a depot at Stockwell, but this closed in 1915. There are sidings at High Barnet for stabling trains overnight.

Future

[edit]Northern line split

[edit]Since the 2000s, TfL has aspired to split the Northern line into two routes.[66][67] Running trains between all combinations of branches and the two central sections, as at present, means only 24 trains an hour can run through each of the central sections at peak times, because merging trains have to wait for each other at the junctions at Camden Town and Kennington.[68] Completely segregating the routes could allow 36 trains an hour on all parts of the line, increasing capacity by around 25%.[66][68]

TfL has already separated the Charing Cross and Bank branches during off-peak periods; however, four trains per hour still run to and from Morden via Charing Cross in the peak; the northern branches to Edgware and High Barnet cannot be separated until Camden Town station is upgraded to cope with the numbers of passengers changing trains.[69] The extension to Battersea would allow the Charing Cross branch to terminate at Battersea Power Station.[70][71]

The proposed split of the Northern line would require Camden Town station to be expanded and upgraded, as the station is already severely overcrowded at weekend peak times, and a split would increase the number of passengers wishing to change trains at the station.[71][72][69] In 2005, London Underground failed to secure planning permission for a comprehensive upgrade plan for Camden Town tube station that would have involved demolition of the existing station entrance and several other surface-level buildings, all within a conservation area.[73][74] New redevelopment plans were first announced in 2013 by TfL, which proposed avoiding the existing station entrance and the conservation area by building a second entrance and interchange tunnels to the north, mostly on the site of a subsequently vacated infant school.[72] In 2018, plans to upgrade and rebuild Camden Town station were placed indefinitely on hold, due to TfL's financial situation.[75] As of 2024[update], TfL said they still "aspire" to split the line. A partial separation was proposed in which all trains from Morden would operate via Bank, while those starting at Kennington (or Battersea) would serve the Charing Cross branch. The High Barnet and Edgware branches would remain served by trains from both routes.[76]

Incidents and accidents

[edit]In October 2003, a train derailed at Camden Town.[77] Although no one was hurt, points, signals and carriages were damaged. Concern was raised about the safety of the Tube, given the derailment at Chancery Lane earlier in 2003.[78] A joint report by the Underground and its maintenance contractor Tube Lines concluded that poor track geometry was the main cause, and therefore extra friction arising out of striations (scratches) on a newly installed set of points had allowed the leading wheel of the last carriage to climb the rail and derail. The track geometry at the derailment site is a very tight bend and tight tunnel bore, which precludes the normal solution for this sort of geometry of canting the track by raising the height of one rail relative to the other.[79]

In August 2010, a defective rail grinding train caused disruption on the Charing Cross branch, after it travelled four miles in 13 minutes without a driver. The train was being towed to the depot after becoming faulty. At Archway station, the defective train became detached and ran driverless until coming to a stop at an incline near Warren Street station. This caused morning rush-hour services to be suspended on this branch. All passenger trains were diverted via the Bank branch, with several not stopping at stations until they were safely on the Bank branch.[80][81]

In popular culture

[edit]- In his debut novel Ghostwritten, David Mitchell characterises the Northern line as "the psycho of the family".[82]

- The Bloc Party song "Waiting For the 7.18" references the Northern line as "the loudest".[83]

- As part of a series of twelve books tied to the twelve lines of the London Underground, A Northern Line Minute focuses on the Northern line.[84]

- The New Vaudeville Band's 1967 song "Finchley Central" ("On Tour" in the US) mentions several stations on the line.[85]

- The Nick Drake song "Parasite" references the Northern Line.[86]

- The 1982 Robyn Hitchcock song "Fifty Two Stations" begins, "There's fifty-two stations on the Northern Line/None of them is yours, one of them is mine."[87]

- The 2021 Maisie Peters song "Elvis Song" begins, "Cold bench on a platform/Last train on the Northern Line."[88]

Maps

[edit]- ^map 1 High Barnet – 51°39′02″N 000°11′39″W / 51.65056°N 0.19417°W

- ^map 2 Totteridge & Whetstone – 51°37′50″N 000°10′45″W / 51.63056°N 0.17917°W

- ^map 3 Woodside Park – 51°37′05″N 000°11′08″W / 51.61806°N 0.18556°W

- ^map 4 West Finchley – 51°36′34″N 000°11′18″W / 51.60944°N 0.18833°W

- ^map 5 Mill Hill East – 51°36′30″N 000°12′37″W / 51.60833°N 0.21028°W

- ^map 6 Finchley Central – 51°36′04″N 000°11′33″W / 51.60111°N 0.19250°W

- ^map 7 East Finchley – 51°35′14″N 000°09′54″W / 51.58722°N 0.16500°W

- ^map 8 Highgate – 51°34′40″N 000°08′45″W / 51.57778°N 0.14583°W

- ^map 9 Archway – 51°33′56″N 000°08′06″W / 51.56556°N 0.13500°W

- ^map 10 Tufnell Park – 51°33′24″N 000°08′17″W / 51.55667°N 0.13806°W

- ^map 11 Kentish Town – 51°33′01″N 000°08′26″W / 51.55028°N 0.14056°W

- ^map 12 Edgware – 51°36′50″N 000°16′30″W / 51.61389°N 0.27500°W

- ^map 13 Burnt Oak – 51°36′10″N 000°15′50″W / 51.60278°N 0.26389°W

- ^map 14 Colindale – 51°35′44″N 000°15′00″W / 51.59556°N 0.25000°W

- ^map 15 Hendon Central – 51°34′59″N 000°13′34″W / 51.58306°N 0.22611°W

- ^map 16 Brent Cross – 51°34′36″N 000°12′49″W / 51.57667°N 0.21361°W

- ^map 17 Golders Green – 51°34′19″N 000°11′38″W / 51.57194°N 0.19389°W

- ^map 18 Hampstead – 51°33′25″N 000°10′42″W / 51.55694°N 0.17833°W

- ^map 19 Belsize Park – 51°33′01″N 000°09′52″W / 51.55028°N 0.16444°W

- ^map 20 Chalk Farm – 51°32′39″N 000°09′12″W / 51.54417°N 0.15333°W

- ^map 21 Camden Town – 51°32′22″N 000°08′34″W / 51.53944°N 0.14278°W

- ^map 22 Mornington Crescent – 51°32′04″N 000°08′19″W / 51.53444°N 0.13861°W

- ^map 23 Euston – 51°31′42″N 000°07′59″W / 51.52833°N 0.13306°W

- ^map 24 Warren Street – 51°31′29″N 000°08′18″W / 51.52472°N 0.13833°W

- ^map 25 Goodge Street – 51°31′15″N 000°08′04″W / 51.52083°N 0.13444°W

- ^map 26 Tottenham Court Road – 51°30′58″N 000°07′51″W / 51.51611°N 0.13083°W

- ^map 27 Leicester Square – 51°30′41″N 000°07′41″W / 51.51139°N 0.12806°W

- ^map 28 Charing Cross – 51°30′29″N 000°07′29″W / 51.50806°N 0.12472°W

- ^map 29 Embankment – 51°30′25″N 000°07′19″W / 51.50694°N 0.12194°W

- ^map 30 Waterloo – 51°30′09″N 000°06′47″W / 51.50250°N 0.11306°W

- ^map 31 King's Cross St Pancras – 51°31′49″N 000°07′27″W / 51.53028°N 0.12417°W

- ^map 32 Angel – 51°31′55″N 000°06′22″W / 51.53194°N 0.10611°W

- ^map 33 Old Street – 51°31′33″N 000°05′14″W / 51.52583°N 0.08722°W

- ^map 34 Moorgate – 51°31′07″N 000°05′19″W / 51.51861°N 0.08861°W

- ^map 35 Bank-Monument – 51°30′47″N 000°05′17″W / 51.51306°N 0.08806°W

- ^map 36 London Bridge – 51°30′18″N 000°05′10″W / 51.50500°N 0.08611°W

- ^map 37 Borough – 51°30′04″N 000°05′35″W / 51.50111°N 0.09306°W

- ^map 38 Elephant & Castle – 51°29′40″N 000°05′59″W / 51.49444°N 0.09972°W

- ^map 39 Kennington – 51°29′19″N 000°06′20″W / 51.48861°N 0.10556°W

- ^map 40 Oval – 51°28′55″N 000°06′45″W / 51.48194°N 0.11250°W

- ^map 41 Stockwell – 51°28′21″N 000°07′20″W / 51.47250°N 0.12222°W

- ^map 42 Clapham North – 51°27′54″N 000°07′48″W / 51.46500°N 0.13000°W

- ^map 43 Clapham Common – 51°27′42″N 000°08′19″W / 51.46167°N 0.13861°W

- ^map 44 Clapham South – 51°27′10″N 000°08′51″W / 51.45278°N 0.14750°W

- ^map 45 Balham – 51°26′33″N 000°09′07″W / 51.44250°N 0.15194°W

- ^map 46 Tooting Bec – 51°26′09″N 000°09′35″W / 51.43583°N 0.15972°W

- ^map 47 Tooting Broadway – 51°25′40″N 000°10′06″W / 51.42778°N 0.16833°W

- ^map 48 Colliers Wood – 51°25′06″N 000°10′42″W / 51.41833°N 0.17833°W

- ^map 49 South Wimbledon – 51°24′56″N 000°11′31″W / 51.41556°N 0.19194°W

- ^map 50 Morden – 51°24′08″N 000°11′42″W / 51.40222°N 0.19500°W

- ^map 51 Golders Green depot – 51°34′22″N 000°11′35″W / 51.57278°N 0.19306°W

- ^map 52 Morden depot – 51°23′51″N 000°11′49″W / 51.39750°N 0.19694°W

See also

[edit]- T. P. Figgis, architect of the City and South London Railway's original stations

- Leslie Green, architect of the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway's early stations

- List of crossings of the River Thames

- London deep-level shelters, most of which are under Northern line stations

- Tunnels underneath the River Thames

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level.

- ^ The stations that the C&SLR were to serve on the W&SR, would not have included all those subsequently built by the Southern Railway. South Morden (not built), Sutton Common, Cheam (not built) and Sutton, would have been served, but Morden South, St Helier and West Sutton were not part of the UERL's plan.

- ^ Charing Cross and Bank branches start immediately south of the station

- ^ Morden and Battersea branches start immediately south of the station

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Northern line facts". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "London Assembly Questions to the Mayor". London Assembly. 2022. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "City Metric". Centre for Cities. 18 September 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Rebecca (29 January 2018). "Northern Line passengers to get quicker and more frequent journeys as TfL boosts services to tackle crowding on busiest Tube line". City A.M. London. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 35.

- ^ Wolmar 2005, pp. 4 & 135.

- ^ Horne 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Horne 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Horne 2009, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Horne 2009, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e Rose 2016.

- ^ Horne 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Wolmar 2005, p. 205.

- ^ "No. 28665". The London Gazette. 22 November 1912. p. 8798.

- ^ a b c Horne 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Horne 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ^ "No. 27380". The London Gazette. 26 November 1901. p. 8200.

- ^ Horne 2009, p. 28.

- ^ a b Horne 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Day & Reed 2010, p. 91.

- ^ "No. 32770". The London Gazette. 24 November 1922. pp. 8314–8315.

- ^ Wolmar 2005, p. 225.

- ^ Chris Sutton. "The Northern Heights". Trains to Beyond.

- ^ a b c d e Jim Blake; Jonathan James (1987). Northern Wastes. Platform 10.

- ^ a b c Tony Beard (2002). By Tube Beyond Edgware. Capital Transport.

- ^ "The Northern line". London Transport Museum.

- ^ Rails through the Clay; Croome & Jackson; London; 2nd ed; 1993; p228

- ^ "London Tubes' New Names – Northern and Central Lines". The Times (47772): 12. 25 August 1937. Retrieved 18 May 2009.(subscription required)

- ^ "Halifax Plane Production by LPTB during WWII" (PDF). Transport for London. November 2020.

- ^ a b c Nick Catford. "Mill Hill (The Hale)". Disused Stations.

- ^ Oliver Green; John Reed (1983). The London Transport Golden Jubilee Book. The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Research Guide No 33: Aldenham Bus Works" (PDF). Transport for London. 27 April 2016.

- ^ Nick Catford. "Edgware (GNR)". Disused Stations.

- ^ Dennis Edwards; Ron Pigram (1988). London's Underground Suburbs. Bloomsbury.

- ^ Railway (London Plan) Committee 1944 (21 January 1946), Report to the Minister of War Transport, pp. 17–18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Strategic Review 1988 – New Lines and Extensions – Northern Line Southern Extension" (PDF). What Do They Know. London Underground. 1988. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Northern Line". Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides.

- ^ Catherine Moore (16 May 2022). "Bank station upgrade: Northern line reopens after blockade success". New Civil Engineer.

- ^ "Next phase of vital upgrade of Bank station completes, with the opening of a new interchange route between the Northern line and DLR". Transport for London. 13 October 2022.

- ^ "Northern Line (Hansard, 17 March 1994)". api.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Pearce, Mike (22 June 1989). "Northern Line driverless trains". Thames Television, Thames News. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Call for action on Northern Line". BBC News. 12 October 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ^ "Tubular hell". The Independent. London. 6 January 1997. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Northern line modernisation". London Transport. 2000. Archived from the original on 16 June 2000. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Corfield, Gareth (9 August 2016). "London's 'automatic' Tube trains suffered 750 computer failures last year". The Register. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Network Tests for New Signalling Systems" (Press release). Tube Lines. 24 August 2005. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008.

- ^ "Operational and Financial Performance Report and Investment Programme Report – Third Quarter, 2012/13" (PDF). Transport for London. 6 February 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ "Northern line upgrade one step closer" (Press release). Transport for London. 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Mayor of London – Transport Commitments" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2021.

- ^ Kessell, Clive. "LU Northern line goes CBTC". Retrieved 5 October 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The Night Tube". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "The Night Tube". Transport for London. n.d. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Topham, Gwyn (27 August 2015). "London night tube plan suspended". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Details of Tube modernisation plans unveiled". Tube Lines. 8 January 2003. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Shawcross, Valerie; Livingstone, Ken (7 March 2005). "Transport Plan – Southward Extensions". Mayor's Question Time. Archived from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b Collier, Hatty (8 November 2017). "Tunnelling work to extend Tube's Northern Line to Battersea completed". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Northern line extension to Battersea gets go-ahead" (Press release). Transport for London. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Northern line extension". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "Battersea Power Station scheme approved" (Press release). London Borough of Wandsworth. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Prynn, Jonathan; Sleigh, Sophia (21 December 2018). "TfL under fire as Battersea Tube extension is delayed". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Northern line extension: Two new Tube stations open". BBC News. 20 September 2021. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Jamie (23 June 2013). "Clapham Junction next for Northern Line says London Assembly member". Wandsworth Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Twin Peaks: Timetable Changes on the Northern Line". London Reconnections. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Abbot 2010, pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b "Bicycle on Tube map" (PDF). Transport for London. June 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Transport 2025: Transport vision for a growing world city". November 2006. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.135.5972.

A segregation of services would deliver simpler service patterns on the line. This will allow more trains to be run through both the West End and City branches – enabling 30tph services on the central London branches. This will provide roughly 25 per cent extra capacity and crowding relief on these busy sections. With the core infrastructure being capable of supporting these service patterns, the main requirements are some additional trains (and stabling) and station capacity improvements at Camden Town.

- ^ Lydall, Ross (12 May 2010). "Northern line service divided in £312m bid to end overcrowding". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Twin Peaks: Timetable Changes on the Northern Line". London Reconnections. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ a b "We Need To Talk About Camden: The Future of the Northern Line". London Reconnections. 6 May 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Permanent split for the Northern line". Your Local Guardian. 15 May 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Plans to split Northern Line in two move forward another step". Rail Technology Magazine. 4 August 2015. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Improving capacity at Camden Town station". Transport for London. 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018. Detailed report, with updated timeline etc.

- ^ "Camden Town Redevelopment". Alwaystouchout.com. 25 January 2006. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ Bull, John (14 October 2015). "Second Time Lucky: Rebuilding Camden Town Station". London Reconnections. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Topham, Gwyn (11 December 2018). "Major tube upgrades shelved as TfL struggles to balance books". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Cooke, Alex (14 April 2024). "TfL still 'aspires' to split Tube line to increase capacity by 20k". My London. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Second Tube train derailed". BBC News. 19 October 2003. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Thirty hurt after Tube crash". BBC News. 25 January 2003. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Track design flaws may have led to Camden Town Tube derailment". New Civil Engineer. 4 December 2003. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Runaway train on London Tube's Northern Line". BBC News. 13 August 2010. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Runaway of an engineering train from Highgate 13 August 2010 (Technical report). RAIB. 2011. 09-2011.

- ^ TJ Dawe. "Literary Excerpt: David Mitchell and the Character of the London Underground Lines". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "BlocParty.net – Waiting for the 7.18". Archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- ^ "A Northern Line Minute, The Northern Line by William Leith". Penguin. 7 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Alan Charles Klein; Geoffrey Stephens (1967). "New Vaudeville Band: Finchley Central". LyricFind. Peermusic Publishing. Retrieved 15 June 2025.

- ^ "Parasite". Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "Fifty Two Stations". Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ "Elvis Song". Archived from the original on 20 June 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abbott, James (February 2010). "Northern Line split planned". Modern Railways. 67 (737). ISSN 0026-8356.

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2010) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (11th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-341-9.

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 185414-293-3.

- Beard, Tony (2002). By Tube Beyond Edgware. Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-246-7.

- Blake, Jim; James, Jonathan (1993). Northern Wastes: Scandal of the Uncompleted Northern Line. London: North London Transport Society. ISBN 978-0-946383-04-7.

- Demuth, Tim (2004). The Spread of London's Underground (2 ed.). London: Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85414-277-1.

- Graves, Robert; Hodge, Alan (1940). The Long Week-End. Faber & Faber.

- Horne, Mike (1987). Northern Line: A Short History. London: Douglas Rose. ISBN 978-1-870354-00-4.

- Horne, Mike (2009). The Northern Line: An Illustrated History (3 ed.). London: Capital Transport Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85414-326-6.

- Lee, Charles Edward (1973). Northern Line. London: London Transport. ISBN 978-0-85329-044-5.

- Lee, Charles Edward (1967). Sixty Years of the Northern. London: London Transport. OCLC 505166556.

- Lee, Charles Edward (1957). Fifty Years of the Hampstead Tube. London: London Transport. OCLC 23376254.

- Murphy, Simon (2005). Northern Line Extensions: Golders Green to Edgware, 1922–24. London: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-3498-8.

- Rose, Douglas (2016) [1980]. The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History (9th ed.). Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-404-1.

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-023-6.