Japanese concession in Tianjin

Japanese concession in Tianjin 天津日本租界 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1945 | |||||||||

Japanese concession in Tianjin | |||||||||

| Common languages | Japanese, Chinese | ||||||||

| Historical era | Qing dynasty / Republic of China | ||||||||

• Established | 1898 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1945 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

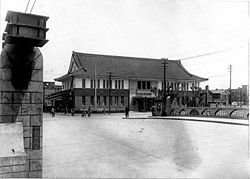

Japanese concession in Tianjin (Japanese: 天津日本租界,Chinese:天津日租界) was one of the Foreign concessions in Tianjin established by the Japanese government during the late Qing dynasty. It was also the largest and only relatively prosperous Japanese concession in modern China, where the prosperity of its architecture “had already surpassed that of some medium-sized cities in Japan proper.”[1]: 52

The concession was located east of the old city and south of the Hai River. It originally covered an area of 0.34 km2, but after multiple expansions, by 1938 it reached approximately 1.5 km2. The Japanese concession in Tianjin was established on the basis of unequal treaties such as the Tianjin Japanese Concession Treaty and the Supplementary Treaty of the Tianjin Japanese Concession. It was one of the most important Japanese concessions in China and served as a key manifestation of Japan's political, economic, and military influence in North China at the time.[2]

The concession enjoyed judicial and police powers independent of the Chinese government and had a complete administrative system. Under the leadership of the Japanese Consulate-General in Tianjin, its governance structure was composed of the Japanese police station, the Japanese garrison, and expatriate self-governing organizations such as the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association and the Tianjin Public Welfare Society. Economically, the concession was heavily dependent on Japanese investment and trade. Factories, trading houses, and industrial enterprises expanded rapidly, and the financial sector was also relatively developed, providing funding to Japanese businesses. Through capital export, Japanese firms directly intervened in the merger and acquisition of Chinese national industries. At the same time, the concession became a hub for smuggling and transshipment of contraband, with large quantities of Japanese goods flooding the North China market, severely undermining Chinese national industry and customs revenues.

Within the concession there were also Japanese banks, schools, hospitals, Buddhist temples, and chambers of commerce, making it the center of settlement and activity for Japanese expatriates in North China. Besides the expatriates, the concession also attracted a number of pro-Japanese elites, such as Puyi, Duan Qirui, Lu Zhongyu, Cao Rulin, Zheng Xiaoxu, and Gao Lingwei, turning it into the site of the “Little Court” of the exiled Qing imperial household. In November 1931, in order to support the puppet state of Manchukuo, the head of the Japanese Special Agency in Tianjin, Kenji Doihara, planned and carried out the Tianjin Incident within the concession, secretly escorting Puyi from Zhang Garden in Tianjin to Northeast China.[3]

The Japanese concession in Tianjin existed from 1898 to 1945. On January 9, 1943, in order to preempt Britain and the United States by formally returning concessions and thus gain political initiative, Japan signed the Sino-Japanese Agreement on the Return of Concessions and the Abolition of Extraterritorial Rights, transferring the concession in name to the Wang Jingwei regime and renaming it “Xingya First District.”[4] After Japan's defeat and surrender in 1945, the Nationalist government of the Republic of China regained the occupied areas, announced the recovery of the Japanese concession in Tianjin, and organized the liquidation of enemy assets.[5]

After 1949, the former properties of the Japanese concession in Tianjin were converted into public ownership, redistributed to government agencies and enterprises, while some courtyards became mixed residential compounds. With the city's expansion, although the area of the former concession lay in the central urban district, it long remained neglected and faced decline. In 2011, the area of the former concession was incorporated into the Anshan Road Historic and Cultural District Preservation Plan. Today, part of its buildings remain, some of which have been listed as key protected or specially protected historic buildings.

Delimitation and Expansion

[edit]

The history of Japan establishing a concession in Tianjin began after the First Sino-Japanese War. On October 19, 1896, the Qing Dynasty's Prime Minister of Foreign Affairs Ronglu and Imperial Commissioner Zhang Yinhuan signed the “Public Diploma” with Japan's Minister Plenipotentiary Hayashi Tō in Beijing. Article 3 of the diploma stipulated: “The Chinese government also consents that, upon Japan's request, Japanese-administered concessions may be established in Shanghai, Tianjin, Xiamen, Hankou, and other locations”.[6]: 686 This clause provided the legal basis for Japan to establish a concession in Tianjin.

On November 22 of the same year, Japan's Minister to China Yano Fumio arrived in Tianjin and negotiated the establishment of a concession with the Beiyang Minister and Governor of Zhili Wang Wenshao.[7] Subsequently, the two countries conducted nearly two years of negotiations over the concession. On October 17, 1897, the Japanese government officially notified the Qing government, proposing the specific boundaries of the Japanese concession.[7]

On August 29, 1898, China and Japan signed the “Tianjin Japanese Concession Articles” and a “Separate Diploma,” in which Article 3 explicitly stated: “Japan is permitted to establish an exclusively-administered concession in Tianjin.”[6]: 798 The defined boundaries were: “The eastern boundary starts from the northern boundary of the Gospel Hall, following the river to the north side of the Liumi Factory and Xingjia Timber Factory, measuring eighty-five zhang; the southern boundary runs in a straight line westward from the northern boundary of the Gospel Hall to the earthen wall, 150 zhang from the British New Concession; the northern boundary runs from the river along the north side of Liumi Factory and Xingjia Timber Factory, around the backyards of existing roads, then west along existing roads to the southeast corner outside the Haiguang Temple moat, following the road to the earthen wall. Along all boundary roads, a three-zhang strip is reserved for future road widening. From this earthen wall, the boundary extends southward to zero zhang at the southern boundary. Both the southwest boundaries are delimited by the earthen wall, leaving a five-zhang-wide road”.[6]: 798 According to the “Separate Diploma,” “China agrees to designate the area from Liumi Factory to the south wall of the Korean Legation, extending west in a straight line to connect with the pre-established Japanese boundary, as the Japanese preparatory concession.” Additionally, Article 2 stipulated: “China agrees to designate a plot below the German concession for the Japanese to build a wharf for their ships”.[6]: 798

On September 21 of the same year, Japan's Consul in Tianjin Zheng Yongchang signed the “Supplementary Articles for the Establishment of the Tianjin Japanese Concession” with the Tianjin Customs Commissioner Li Minchen, accompanied by the “Supplementary Diploma.” These documents regulated road construction, taxation, land and property prices, and police and public security within the concession and preparatory concession. Based on these agreements, Japan obtained judicial and police authority within the concession.[8]: 194–195 [9]

On January 5, 1901, Zheng Yongchang unilaterally announced an expansion of the concession, proposing to extend the original Japanese concession southeastward toward the Tianjin city proper. The boundaries were: northeast from the sluice gate, following the Hai River downstream to the French concession; northwest from the sluice gate westward along the city moat winding to the South Gate; southwest from the South Gate southward to Haiguang Gate; and then from Haiguang Gate along the earthen wall in a straight line to the Hai River, connecting with the French concession.[9]

History

[edit]Early Stage (1898–1911)

[edit]

The area of the Tianjin Japanese Concession was originally a swampy land in the southeastern part of Tianjin city. Because of the high difficulty of development, both the British and French concessions avoided this area when they were established in the 1860s.[7] After the Japanese concession was demarcated, Japan's national power was still limited, with its main focus on domestic development, and it was unable to carry out full-scale development of the concession. Moreover, most early Japanese residents in Tianjin were small merchants with weak economic capacity, struggling even for their own livelihood, and were thus unable to undertake the heavy responsibility of developing the desolate swamp.[7] As a result, in its early years the concession was almost neglected; it was even said that “within two years after its establishment, not a single Japanese settled there.” Most Japanese residents still preferred to rent houses and open shops in the British and French concessions.

In 1899, the Japanese government adopted the proposal of Consul Tei Eisho (郑永昌), formulating policies for managing the concession.[9] In March 1900, the Japanese government issued the “Regulations of the Concession Management Office” and related decrees, establishing the Japanese Exclusive Settlement Management Office, located on Zhako Street in Tianjin. Consul Tei Eisho served concurrently as director; Takeo Nagasaki was appointed engineer; Kogiku Nishikoji and Masuda Mataichi as technicians; and Oeda Yoshihiro as secretary, responsible for land acquisition, design, and the first phase of reclamation works.[7]

In 1902, due to the concession's weak finances, Tokyo Tatemono Co., Ltd. was entrusted with land reclamation and housing construction.[10][11] After 1903, large-scale land reclamation projects were gradually carried out, enabling the area to become suitable for development and construction.

Period of Development and Prosperity (1912–1931)

[edit]

After the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, frequent turmoil and warfare erupted in Chinese-administered areas, prompting many citizens and merchants to move into the foreign concessions. Owing to its geographical proximity to the Chinese city, the Japanese concession became one of the earliest main destinations.[7] At the same time, natural disasters and social unrest drove large numbers of political refugees and victims to Tianjin, stimulating urban development and boosting the growth of all the foreign concessions.[7] Because the Japanese concession bordered Chinese neighborhoods, it became an important refuge. In 1913, the “Minutes of the Residents' Assembly in the Japanese Concession” recorded: “Since the 1911 Revolution, the number of Chinese relocating to our concession has steadily increased, as has our Japanese population; there is no doubt our concession will further develop in the future.”[12]: 3 By 1913, nearly twenty enterprises were operating in the Japanese concession, covering printing, food, tobacco, soap-making, and other industries.[13]

In November 1931, in response to Japan's invasion of Northeast China after the Mukden Incident, Kenji Doihara, head of the Japanese Special Service Agency in Tianjin, planned and carried out a series of secret operations within the Japanese concession. These aimed to covertly escort Puyi, who was then residing in Zhang Garden, to the Northeast—a scheme later known as the Tianjin Incident.[3] The operations included intelligence control, arrangement of escape routes, and coordination with the Kwantung Army, all designed to conceal Puyi's whereabouts and ensure his safe transfer.[3] Ultimately, in the same month, Puyi left Tianjin for the Northeast and, in the following year, became the puppet emperor of Manchukuo under Japanese sponsorship.[3]

Period of Distorted Prosperity (1932–1937)

[edit]

After the September 18 Incident of 1931, Japan advanced the policy of “Sino–Japanese economic cooperation.” On the one hand, this was intended to ease anti-Japanese sentiment both internationally and within China; on the other, it aimed to strengthen Japan's exploitation of North China's economic resources. Major Japanese zaibatsu began investing in Tianjin, establishing industries such as textiles, flour milling, papermaking, and steel.[13] The factories founded during this period were no longer confined to the Japanese concession itself, with most being located in advantageous areas outside the concession.[13]

In May 1935, Hu Enpu, president of Guoquan Bao in the Japanese concession, and Bai Yuhuan, president of Zhen Bao, were successively assassinated, an event historically known as the Hebei Incident.[14] Following the incident, Lieutenant General Sakai Takashi, Chief of Staff of the China Garrison Army, and Takahashi Tan, Military Attaché of the Japanese Embassy in China, met with He Yingqin, Acting Chairman of the North China Branch of the Nationalist Government's Military Affairs Commission. They claimed the assassinations were “anti-foreign acts” and threatened that, unless the Chinese government took effective measures, Japan would be forced to take “self-defense” actions.[14] Soon after, Japanese garrison troops in Tianjin staged an armed demonstration in front of the Hebei Provincial Government building and conducted street-fighting exercises. Ultimately, this incident became an important factor leading to the signing of the He–Umezu Agreement.[14]

By this time, land within the Japanese concession could no longer meet the needs of the growing Japanese population. Japanese trading companies and merchants began to illegally purchase land outside the concession under various pretexts. By 1937, they had accumulated over 10,000 mu of land.[15]: 99

Tetsurō Yagi, who was born and spent his youth in Tianjin, recalled this period in his memoir A Japanese Boy in Tianjin: “The streets bearing Japanese names were neat and orderly, and Japanese signboards grew increasingly common. Although the brick-built Western-style houses and apartments did not match the prosperity and beauty of the British and French concessions, they already surpassed those of some medium-sized cities in Japan proper.”[1]: 52

Japanese Occupation of Tianjin (1937–1945)

[edit]

On July 30, 1937, the Japanese army fully occupied Tianjin. Japanese political control expanded rapidly from the Japanese concession into the Chinese-administered city, where they supported the establishment of the Tianjin Committee for Maintaining Public Order as a puppet regime to govern the Chinese districts. In religious affairs, Japan tightened its control over Tianjin, suppressing local Buddhist activities,[16] while Japanese missionaries intervened in and took control of Christian churches.[17] As Japan consolidated its dominance in Tianjin, some foreign firms gradually shifted from the British concession to the Japanese concession, forming a “dual-center” pattern along “Middle Street of the British concession—Asahi Street of the Japanese concession.”[18]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Japanese army regarded the British concession in Tianjin as an obstacle to the establishment of a “New Order in East Asia.”[19] Between 1938 and 1939, the Japanese repeatedly pressured the British concession to extradite anti-Japanese figures. On June 14, 1939, they imposed a full blockade of the British and French concessions in Tianjin, forcing Britain to abandon its pro-China policy.[19] During the blockade, Japan carried out strict searches of British nationals to create pressure, provoking a strong reaction from the British side.[20] With German and Italian support, Japan compelled Britain to compromise, resulting in the 1940 Tianjin Agreement, which ended the blockade.[19]

Before 1941, despite diplomatic conflicts with Britain, the Japanese army generally respected the extraterritorial rights enjoyed by various powers in the Concessions in Tianjin, and thus Tianjin was not yet under full Japanese occupation. After the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, however, the Japanese army occupied the British concession in Tianjin and transferred it to the pro-Japanese Reorganized National Government of China (Wang Jingwei regime).[10] At the same time, the Japanese authorities took over British and American church institutions and their affiliated hospitals, schools, and other properties, while British and American residents and missionaries were sent to the Weihsien Internment Camp in Shandong.[21]

Japanese Defeat and Reversion of the Concession

[edit]

In January 1943, Britain and the United States announced the return of their concessions in China to the Nationalist government. In order to take political initiative before the Allies, Japan signed the “Sino-Japanese Agreement on the Return of Concessions and Abolition of Extraterritoriality” with the Wang Jingwei regime on January 9, 1943, proclaiming the “return” of its administrative rights in China to the Nationalist government.[4]

According to this agreement, on March 30, 1943, Japan formally transferred the Tianjin Japanese Concession to the Wang Jingwei regime.[10] On April 8, 1943, the Tianjin Special Municipality government issued an order renaming the former concession “Xingya First District” and appointing Zhang Tongliang (son of former Beiyang Finance Minister Zhang Hu) as district chief.[22] Despite this, the original system of the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association largely remained in place, with real administrative authority still held by the Japanese. District officials were subordinate to the association's leader, Usui Chuzō. Thus, although the Tianjin Japanese Concession was “returned” in name, it remained under Japanese control in practice.[10]

On August 15, 1945, Japan announced its unconditional surrender. On October 6, the surrender ceremony for Japanese forces in Tianjin was held in front of the headquarters of the U.S. Marine Corps' III Amphibious Corps (the former Tianjin French Municipal Council building). On November 24, the Executive Yuan of the Nationalist Government issued the “Regulations for the Acceptance of Concessions and the Legation Quarter in Beiping,” formally recovering the Tianjin Japanese Concession.[23]: 1286 In December, the Enemy and Puppet Property Disposal Bureau for the Pingjin Area was established in Beiping (now Beijing), with an office in Tianjin to receive and manage all types of public and private assets held by the Japanese government, army, and civilians, including those in the concession.[15]: 432 The following year, Tianjin carried out a comprehensive clean-up of all concessions, which was completed in May 1947.[2]

Administration of the Concession

[edit]Japanese Consulate General

[edit]

In the first year of the Guangxu reign (1875), the Japanese government established a consulate in Tianjin, which was upgraded to a consulate general in 1902, becoming an important diplomatic base for Japan in North China.[7] During the first half of the 20th century, the Consulate General actively intervened in and manipulated affairs in northern China. It convened the Conference of Consuls General in China in 1935 and the North China Consular Conference in 1937, closely linked to the establishment of the East Hebei Autonomous Government and the outbreak of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. The Consulate General maintained multiple functional departments and an extensive intelligence network, collecting political, military, and economic information. Its jurisdiction covered areas such as Qingdao, Jinan, and Zhangjiakou, serving as Japan's administrative and intelligence hub in North China.

The consulate was initially housed in an American expatriate residence and relocated several times before moving into a new building on Miyajima Street in 1915.[7] In 1943, after the nominal return of the Tianjin Japanese Concession to the Wang Jingwei regime, the Japanese Residents' Association in Tianjin took over its operations. The original consulate premises were demolished after the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

Several diplomats who once served here later became prominent political figures in Japan, including Hachirō Arita, Shigeru Kawagoe, and Shigeru Yoshida.[24]

Japanese Police Station

[edit]

The Japanese police presence in Tianjin can be traced back to the 22nd year of the Guangxu reign (1896), when only a small police force was stationed inside the Japanese Consulate.[25]: 855–856 In 1898, under the “Additional Articles for the Establishment of the Japanese Concession in Tianjin,” Japan obtained police authority within the concession.[26]

After the outbreak of the Boxer Uprising, the Japanese government dispatched two police inspectors and thirty constables, who were stationed in a field post office in front of the Japanese Consulate at Zizhulin. Shortly afterward, a police detachment was established on Zhagou Street in the concession, under the jurisdiction of the Consulate-General of Japan in Tianjin.[7] In 1915, the detachment moved with the Consulate-General to its new site on Miyajima Street, and it was formally renamed the Japanese Police Station, commonly referred to as the “White Hat Yamen”.[25]: 855–856 It was responsible for maintaining public order in the concession, managing household registration, handling disputes, and exercising consular jurisdiction. The police station was staffed by Japanese officers and employed some Chinese patrolmen as auxiliaries.[7] Its judicial division, headed by a Japanese police inspector, acted as prosecutor and exercised consular jurisdiction, granting it significant authority over both Japanese residents and Chinese citizens in Tianjin.[26]

Although dispatching police to treaty ports beyond concessions and even to non-open regions was illegal, in the early 1930s, the Consulate-General, citing the need to “protect Japanese and Korean nationals,” gradually established several police branches to expand its control. The Japanese Police Station's influence extended not only across the concession and parts of the Chinese-administered districts of Tianjin but also progressively along railway lines. Police substations or outposts were set up in places including Qinhuangdao, Shanhaiguan, Tangshan, Fengtai, Yutian, Dongguang, Cangzhou, Qikou, Shijiazhuang, and Baoding, forming a policing network that covered much of North China.[25]: 855–856

In January 1943, the Japanese government announced the transfer of the concession to the Wang Jingwei regime, and the Japanese Police Station was merged into the Tianjin Special Municipality Government.[25]: 855–856

Japanese Residents' Association

[edit]

In the 28th year of the Guangxu era (1902), the Japanese Consulate in Tianjin established the “Tianjin Japanese Concession Office” to manage the Japanese concession on Asahi Street. In 1907, the “Foreign Residents’ Association Law” was implemented, and the Japanese residents formed the Tianjin Japanese Residents’ Association, replacing the Concession Office. Its jurisdiction initially covered the concession and the surrounding two li (expanded to three li from 1938).[2] In 1914, the association moved into the newly built Tianjin Japanese Public Assembly Hall in Yamato Park.[27]

As a self-governing organization for Japanese residents in Tianjin during the first half of the 20th century, the Residents’ Association was the main authority in the Japanese concession, combining legislative and administrative functions under the leadership of the Consulate-General of Japan in Tianjin.[2] The association was responsible for regulations, elections, financial and tax matters, infrastructure construction, electricity management, healthcare and epidemic prevention, sanitation, education management, as well as surveys and coordination within the concession.[27]

In its early years, the association primarily relied on boat and cart taxes for funding, but these taxes applied only to Chinese operators; Japanese residents, Chinese residents, and other foreigners in the concession were exempt.[7] As road repairs and other public projects expanded, funding became insufficient. Beginning in January 1905, the association imposed license taxes on special trades, including geisha, restaurants, inns, theaters, and teahouses, and also implemented dock fees.[7] With the rise of the boycott of Japanese goods movement, especially after the September 18 Incident, the association's financial revenue was severely affected. It even requested debt repayment delays from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) and responded to difficulties by reducing staff and cutting expenditures.[7]

The Tianjin Japanese Residents’ General Assembly was the highest authority of the association, responsible for reviewing budgets, taxation, education, and public health. The Administrative Committee, elected by the General Assembly, handled the day-to-day administrative affairs of the association, functioning similarly to the Tianjin British Municipal Council Board of Works. In 1934, the committee was downsized to seven members and renamed the Council of Advisors. In 1936, a “President System” was implemented to further centralize authority.[27] The committee also established investigation committees as advisory bodies, covering special areas such as taxation, education, dock construction, and regulations.

Tianjin Gongyi Association

[edit]

The Tianjin Japanese Residents' Mutual Aid Association (Kyōeki-kai) was planned in 1927 by Kato Sotomatsu, the Japanese Consul-General in Tianjin, Usui Chūzō, chairman of the Tianjin Japanese Concession Administrative Committee, and Nakajima Tokuji, a director of the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association. It was officially established in January 1930 after approval by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan).[7] The Kyōeki-kai aimed to protect and promote the common interests of Japanese residents in Tianjin, carrying out activities in worship, education, health, and other necessary areas.[28]: 2 After the “September 18 Incident” in 1931, as Japanese influence in North China expanded, the Kyōeki-kai increasingly coordinated with the Tianjin Japanese Police Station and the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association, gradually involving itself in propaganda, ideological control, and resource mobilization.[7]

After the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, part of the Kyōeki-kai's functions was integrated into the newly established Japanese Residents' Association, cooperating with the Japanese military to implement wartime administration. In January 1943, when the Tianjin Japanese Concession was nominally “handed over” to the Wang Jingwei regime and renamed “Kōa District 1,” the Kyōeki-kai continued to exist under the new administrative framework, assisting in managing expatriates and maintaining the so-called “Kōa order”.[10] Following Japan's defeat and surrender in 1945, the Tianjin Kyōeki-kai was dissolved along with other Japanese expatriate organizations in China, and its assets and archives were taken over by the Republic of China government.[10]

Japanese Garrison

[edit]

The China Garrison Army, originally called the Qing Garrison Army, was the Japanese garrison force that arrived in Tianjin on April 22, 1901. Initially numbering about 1,700 soldiers, its strength had increased to 2,600 by the end of 1901.[7] Its original purpose was to safeguard Japanese interests in the Qing Empire and assist in controlling the Qing government. The troops were first stationed in the British concession in Tianjin, and later constructed barracks and a headquarters in the Haiguang Temple area. Because its headquarters was located in Tianjin, the force was also referred to as the Tianjin Garrison Army.[29]

With the Qing court's return to Beijing, the foreign troops in China were gradually reduced in strength from 1902 onwards. The Japanese Garrison was also withdrawn in two stages, and by October 1908 the force stationed in Tianjin had been reduced to two infantry companies.[29] After the Mukden Incident of 1931, Itagaki Seishirō visited the garrison headquarters at Haiguang Temple on October 29 and, after obtaining the garrison's support, collaborated with its commander Kohei Kashii to impose martial law in the concession, under cover of which Puyi was secretly escorted out.[7] During the Japanese invasion of China, the garrison cooperated with the Kwantung Army in military operations to expand Japanese influence in North China, bribing collaborators, supporting puppet regimes, and plundering economic resources.[29]

The Tianjin Garrison Army was also involved in educational and public health initiatives for the expatriate community. For example, when the third commander, Akiyama Yoshifuru, left office in 1903, he donated the entire US$700 presented to him by the Japanese residents to the Japanese Residents' Primary School.[30]: 86 In September 1917, when Tianjin suffered a major flood that submerged the Haiguang Temple barracks, the garrison worked with concession authorities and Japanese residents to drain the area and also contributed funds to the East Asian Hospital.[30]: 132

Because of its role in protecting the expatriate community, the garrison reinforced the imperial subject consciousness of overseas Japanese. Many residents believed that “the rise and fall of the Tianjin Japanese concession was inseparable from the Garrison Army.”[31]: 142–143 In times of crisis, the Japanese Residents' Association generally followed the directions of the consulate and the garrison. For example, during the Mukden Incident, the community organization, acting under the guidance of the military and the consulate, mobilized fully to protect the concession and the safety of its residents.[7]

Economy

[edit]Foreign Trade

[edit]

After Tianjin was opened as a treaty port, large numbers of foreign merchants and commercial institutions entered, and ships and goods successively arrived at Tianjin Port. In the early period, most of Tianjin's foreign trade was transshipped via Shanghai, but there was also direct trade with Japan and Siam.[32]: 3 In 1878, Mitsui & Co. chartered the French ship Saint Marie to import flour into Tianjin and established an office there to deal in coal, grain, and lamps. This move is regarded as the beginning of Japan's trade with North China.[33]: 439 However, for more than twenty years after the opening of the port, Japanese merchant ships never entered Tianjin, until 1884, when two Japanese steamships arrived for the first time.[7] In 1886, the Tianjin Customs Trade Reports recorded: “A new route was opened between Tianjin and Nagasaki, increasing the tonnage of Japanese ships to 9,195 tons”.[32]: 140 That same year, Nippon Yusen Kaisha opened a direct shipping line from Tianjin to Incheon and Nagasaki, attracting some Japanese merchants to settle in Tianjin. The number of Japanese residents gradually increased, and some Japanese banks also began negotiating the establishment of branch offices in Tianjin.[32]: 141

However, before the establishment of the Japanese concession, fewer than 18 Japanese vessels reached Tianjin annually on average, and Japanese merchants engaged in the trade of sundries and medicines were mostly scattered around the walled city of Tianjin. After the concession was established, Tianjin's trade with Japan grew rapidly. In 1905, Osaka Shosen Kaisha opened a route from Osaka to Tianjin, with one sailing every six days, calling at Kobe, Moji in Kitakyushu, Shimonoseki, and Zhifu, before finally arriving at the wharf along the Japanese concession in Tianjin's Zizhulin area.[34]: 106 The 1906 Tianjin Customs Annual Report noted: “The total value of goods brought directly from overseas this year amounted to 4 million taels of Haikwan silver, of which about 1.2 million were carried by Japanese ships. Among all kinds of sundries, those from Japan were the largest,” indicating that Japan's trade with Tianjin was already comparable to that of Britain.[32]: 250

Smuggling

[edit]Smuggling in the Japanese concession of Tianjin emerged almost simultaneously with its establishment.[7] As early as the beginning of the 20th century, Japanese residents were already purchasing silver and copper coins in Tianjin and secretly shipping them back to Japan.[7] With the expansion of Japanese influence in China, smuggling gradually evolved from scattered individual acts into organized and systematic activities.[7]

After the signing of the Tanggu Truce in 1933, Japan's political and military power in North China grew significantly, and smuggling reached its peak.[7] Thanks to the Japanese concession serving as a safe haven, Tianjin became the most rampant smuggling hub in North China. Numerous Japanese merchants, including major trading companies under conglomerates such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi, were involved in the trade, which covered goods ranging from sugar, rayon, woolens, and kerosene to cigarettes, pharmaceuticals, and even narcotics.[7]

Between 1935 and 1936, the scale of smuggling in Tianjin expanded dramatically. In May 1936, the amount of smuggled sugar passing through Tianjin reached 50,000 tons—four times the volume of normal imports—causing a sharp decline in legitimate trade with Japan through Tianjin Port and a substantial loss in customs revenue.[32]: 503 At the same time, two to three hundred “foreign firms” clustered in the Japanese concession were engaged in selling smuggled goods. These products flooded the Tianjin market and were continuously transported by rail and road to other parts of China.[35] With low or even no duties, Japanese goods were dumped at low prices, making it impossible for China's national industries to survive. Large numbers of local enterprises in Tianjin, such as textile and leather manufacturing, collapsed, and Chinese-owned businesses went bankrupt one after another. At the time, the Japanese concession in Tianjin was already being referred to as the “headquarters of smuggling and narcotics”.[7]

Although criticism also arose within Japan, pointing out that smuggling harmed the country's reputation, the combined interests of the military and the zaibatsu meant that no one could stop it.[30]: 207 In practice, smuggling worked hand-in-hand with military occupation and became an important means for Japan to dominate North China economically.[7]

Commerce

[edit]

Retail trade in the Japanese concession of Tianjin was mainly concentrated along Asahi Street and in the southern market area of Tianjin. In 1926, under the persuasion and inducement of the Japanese Consul General in Tianjin, managers from the Hong Kong head office and the Shanghai branch of Sincere Department Store jointly invested more than 30,000 yuan to purchase over 1,000 square meters of land on Asahi Street for the construction of Zhongyuan Department Store.[2] The building was designed and built by Kita Engineering Company, with a total investment of 470,000 silver dollars, and formally opened on New Year's Day in 1928 with a ribbon-cutting ceremony by Li Yuanhong.[2]

Because the Consulate-General of Japan in Tianjin strictly regulated the attire of Japanese residents, they generally wore Western suits in public activities, only donning traditional kimono during major Japanese national celebrations.[36] This encouraged the rapid growth of the suit-making industry within the concession. More than thirty establishments—including Idzutsuya Suit Shop, Tsuruno Suit Shop, Yamashita Suit Shop, Kinoshita Trading Company, Yokohama Trading Company, and Wada Suit Shop—emerged, forming a sizeable local cluster of the clothing industry.[2]

Finance

[edit]

The establishment of Japanese financial institutions in Tianjin began in 1899 with the founding of the Yokohama Specie Bank Tianjin Branch.[7] Subsequently, Japanese capital gradually expanded its financial activities in Tianjin: in 1912, Suzuki Takachika, Hirabayashi Gisaburō, and Okitensuke Jirō founded the Tianjin Chamber of Commerce and Industry Bank, which merged with the Beijing Industrial Bank in 1920 to form the Tianjin Bank. The establishment of branches by Choryo Bank (1915), Korean Bank (1918), and Daito Bank (1922), as well as the Sino-Japanese joint venture Huaxia Bank, a cooperative between Beiyang bureaucrats and Japanese capital, in 1924, completed the formation of a Japanese-dominated banking system in Tianjin centered on Yokohama Specie, Korean, Choryo, and Daito Banks.[7]

Yokohama Specie Bank and the Korean Bank focused on large-scale international trade financing and served as the main financial support for Japanese merchants in China, while other institutions specialized in small loans.[7] Trading houses such as Mitsui, Takezai, and Nisshin also relied on the funds provided by Yokohama Specie Bank for import and export activities. Between 1915 and 1931, the bank actively promoted the expansion of Japanese trading houses in Tianjin and the exploitation of local resources through multiple channels.[7]

In 1930, due to the sharp decline of the silver dollar, reduced purchasing power, and weak import and export trade, Tianjin's financial sector temporarily fell into difficulty, and Japanese merchants generally suffered setbacks.[37]: 216 However, between 1932 and 1936, Japanese banks leveraged financial capital to sell large quantities of goods in North China and directly intervened in mergers of Chinese national industries through capital investment. Japanese banks played a key role in the acquisitions of textile mills such as Yuda, Yuyuan, Huaxin, and Baocheng in Tianjin.[7]

At the same time, the Japanese community also established small-scale financial institutions, such as the Tianjin Trust and Industrial Company and the Sino-Japanese Cooperative Savings Society, primarily serving the Japanese residents in Tianjin.[7]

General Industry

[edit]The privileges for Japanese to establish factories in China originated from the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which stipulated that “Japanese subjects may engage freely in all kinds of manufacturing in Chinese treaty ports and cities”.[6]: 616 Subsequently, Japan gradually expanded its investments in China and began setting up factories.[7] The earliest Japanese-owned factory in Tianjin appeared in 1896, when Sanko Trading Company's Sanko Kōkō established a soda factory, which was Tianjin's first starch factory. It mainly produced “Bijin Brand” soap and was popular among Japanese residents in China.[7]

Thereafter, Japanese industrial investment gradually extended to light industries such as glass and lamps.[7] In 1909, Eishin Material Factory was established on Fukushima Street in the Tianjin Japanese concession, funded and operated by Naruse Shinzō, specializing in the production of lamps and lampshades.[38]: 14–15 By 1911, Japanese merchants had founded factories in Tianjin capable of processing 5,000 jin of raw cotton per day.[32]: 300 By the end of 1912, Japanese-operated manufacturing included two glass factories, as well as one soap factory and one axle-making factory.[39]: 497 In 1913, Japanese factories in Tianjin further expanded, including Mōtai Trading Company, Mitsui Ironworks, and a cotton-ginning factory, totaling eight factories.[40]: 13

After World War I, Japan's economic strength increased, and Japanese capital entered China on a large scale, promoting the development of light industry, textiles, food, chemicals, flour, and matches.[7] Following the 1929 global economic crisis and the September 18 Incident, Japanese investment in Tianjin accelerated further. The number of factories and scale of capital expanded rapidly. By 1937, there were 72 major Japanese-owned factories in Tianjin with total capital of approximately 74.05 million yuan, gradually forming a pattern in which Japanese enterprises dominated Tianjin's industry.[7]

Textile Industry

[edit]After the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan's cotton yarn production increased sharply, leading to domestic oversupply, which prompted an active expansion into overseas markets. Initially, exports were directed to Shanghai, but stable sales channels were not established, so attention shifted to Tianjin. With a surge in imports, Tianjin gradually became a distribution center for textiles in North China.[34]: 371 During World War I, local textile industries in Tianjin began to emerge, and a boycott of Japanese goods made it difficult for Japanese merchants to directly participate in production. Even before the September 18 Incident, there were still no Japanese-operated textile factories in Tianjin; Japanese capital was only invested in Chinese yarn factories in the form of loans.[7] The 1922 Tianjin Customs Trade Report even noted that “the position held by the Japanese in the cotton industry has declined, diminishing day by day”.[32]: 492

Subsequently, as Chinese-owned yarn factories fell into financial crises, Japanese merchants began to seize opportunities to penetrate the market. In 1925, Yuda Yarn Factory was forced to sell at a discounted price due to debts, becoming a Sino-Japanese joint enterprise.[7] Between 1931 and 1936, factories such as Yuyuan, Huaxin, and Baocheng were successively acquired, with Yuyuan and Huaxin merged into Kanebo in 1935. In 1936, the Tianjin Textile Club was established, and together with Yuda Yarn Factory, they became major fiber enterprises of Toyo Takushoku in North China. By the outbreak of the 1937 incident, Japanese merchants controlled approximately 70% of cotton textile factories in Tianjin.[7] Unlike British capital, which was largely dispersed in commerce, real estate, and concession construction, Japanese capital concentrated on key industries such as cotton textiles and iron smelting. They not only controlled production but also leveraged market, technological, and policy advantages to establish an exclusive sphere of influence similar to that in Manchuria.[7]

Municipal Construction

[edit]Roads

[edit]The streets of the Tianjin Japanese Concession were characterized by “narrow alleys and a dense road network”,[41] and their naming reflected strong colonial influences.[22] In 1902, the Tianjin Japanese Concession built three main boundary roads along the Haihe River, Huashi, and the French Concession. Their names were derived from three Japanese military officers stationed in Tianjin at the time: Yamaguchi Street along the Haihe River (now Zhang Zizhong Road) was named after Lieutenant General Yamaguchi Motomi, commander of the Fifth Division; Fukushima Street, at the boundary with Huashi (now Duolun Road), was named after Brigadier General Fukushima Yasumasa, commander of the provisional dispatch unit; and Akiyama Street, at the boundary with the French Concession (now Jinzhou Road), was named after Brigadier General Akiyama Yoshifuru, commander of the Tianjin garrison.[22]

Streets such as Matsushima Street and Miyajima Street were named after famous scenic spots in Japan, while streets like Azuma Street, Okitsu Street, and Mishima Street were named after places in Japan's homeland, reflecting the nostalgia of overseas Japanese residents.[22] Yamato Street's naming symbolized Japanese national prestige.[22] Streets such as Asahi, Rong, Tokiwa, and Penglai were named after flowers, plants, and trees—for example, Asahi Street was named after the dawn grass, a type of cherry blossom, symbolizing remembrance of the homeland.[22] Names such as Matsushima, Hashidate, Fusō, and Yoshino were derived from Japanese warships during the First Sino-Japanese War.[22]

After Japan's defeat, many street names in the former Japanese Concession were decolonized. For instance, the former Yamaguchi Street is now part of Zhang Zizhong Road, Shou Street and Xinshou Street were renamed as different sections of Xing'an Road, and Asahi Street became the modern Heping Road.[22] In addition, some original streets no longer exist, such as portions of Zhakou Street and Asahi Street.[22]

City Blocks

[edit]The extensive distribution of long east–west blocks in the Tianjin Japanese Concession was a direct result of early planning controls over street spacing and the overall urban layout.[42] From the outset, site selection for the concession emphasized connectivity with the Old City of Tianjin, and the overall plan stressed the addition of transverse roads to ensure convenient access between the concession and the old city. This resulted in transverse street spacing being smaller than that of longitudinal streets, leading to a noticeably higher number of east–west blocks than north–south blocks.[42]

In terms of block length-to-width ratios, planning also differed across periods. The construction of the original Japanese concession can be divided into three stages: the early stage had small, uniform blocks with length-to-width ratios mostly between 3:2 and 2:1; in the middle stage, blocks on the east side maintained a 3:2 ratio, while those on the west side became significantly larger, showing abrupt changes; in the later stage, blocks were clearly differentiated, with complex and diverse forms.[42]

Parks

[edit]

In the early planning of the Tianjin Japanese concession, park land was explicitly designated, reflecting the importance of parks in Japanese modern urban planning concepts.[43] The construction and design of Yamato Park began in 1908. As an important cultural landscape within the Tianjin Japanese concession, its design was influenced by traditional Japanese garden art and urban planning concepts. The Tianjin Shrine within the park was built in 1915, enshrining Amaterasu Ōmikami and Emperor Meiji. The shrine architecture adopted the traditional Japanese Shinmei-zukuri style,[44] reflecting the influence of Japanese culture on the Tianjin Japanese concession.[45] Yamato Park was not only a place of entertainment and leisure for Japanese residents, but also a platform for demonstrating colonial power and cultural symbolism.[11]

In 1945, following Japan's defeat and the reclamation of the Japanese concession, the nature of Yamato Park underwent significant changes. The Nationalist Government decided to convert the park into a Martyrs' Shrine, serving as a memorial for revolutionary martyrs.[45] In 1949, historical sites in the area were demolished, and the original shrine and garden structures no longer existed.[45] In 1960, the Tianjin Municipal Government constructed the “Bayi Auditorium” on the original site as a new cultural facility and historical symbol.[45]

Drainage

[edit]

The Tianjin Japanese Concession contained many uneven areas, making drainage a significant concern. From its early construction stages, the concession began adopting practices from the British and French concessions, laying a modern concrete sewer network and using water pumps to drain low-lying areas with poor natural drainage.[46]

In the area east of Asahi Street, the sewer pipes were relatively small in diameter. Wastewater from all channels ultimately converged at Kyoritate Street and discharged into the Hai River, with pumping stations installed to assist drainage during high tides or heavy rain.[46] In the area west of Asahi Street, between Matsushima Bridge and Miyajima Bridge, three outlet channels were set along the Wall River (Qiangzihe), and a pumping station was built on Sumiyoshi Street to cope with high tides in the Wall River and seasonal rainfall. In the western expansion area beyond the Wall River, population density was lower, pipelines were laid later, and sewer diameters were larger. Two outlets were set along the Wall River; because the outlets were higher than the river channel, wastewater could flow naturally due to the elevation difference, so no pumping station was needed.[46]

Society

[edit]Education

[edit]

After the establishment of the Japanese concession in Tianjin, the commander of the gendarmerie, Jitsudō Kumamoto, stated: “The strength of our soldiers as a foundation of the nation indeed lies in the spread of education”,[47]: 1 emphasizing the importance of promoting education in China. At the same time, since “the Nichiritsu Gakkan was established as a by-product of military construction,” Japanese military works had damaged civilian houses, and it was hoped that founding a school would ease residents' resentment and mitigate local hostility toward Japan.[47]: 1 The Japanese garrison further believed that, after the Boxer Uprising, since the Japanese army had occupied Chinese districts, it was necessary to establish schools to teach the Chinese population the Japanese language.[48]: 237–238

In December 1900, on the proposal of Jitsudō Kumamoto, Japan leased land on the Baihe riverbank at the site of Hu Youci Temple within the Japanese concession to establish the “Nichiritsu Gakkan”.[47]: 3 It was specifically intended to provide education for Chinese children living in the concession and was the first school founded by Japan in Tianjin.[47]: 3 In 1906, the Nichiritsu Gakkan was renamed Tianjin Higher School, and in 1908, the affiliated Gongli Primary School was founded.[49] In January 1913, Gongli Primary School merged with Tianjin Higher School to become Gongli School.[50]

The Japanese Girls' High School in Tianjin was founded in April 1921 and was officially recognized by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Education as a “designated overseas girls' high school”.[7] In 1930, it was renamed “Tianjin Japanese Girls' High School.” In May 1931, it moved into a newly constructed campus at the intersection of Matsushima Street and Awaji Street. By 1936, the school had an enrollment of 135 students.[51]: 443–444 In 1941, the school was renamed again as “Tianjin Matsushima Japanese Girls' High School”.[52]: 328

Religion

[edit]

Religious activities within the Japanese concession in Tianjin mainly included Buddhism, Christianity, and Japanese Shinto. In 1899, the Nishi Honganji changed its Mission Affairs Bureau into a Propagation Bureau. The sect leader Ōtani Kōzui began his “tour of China,” visiting Tianjin and other places to investigate the expansion of missionary work, and also met with figures such as Li Hongzhang.[53] In 1903, overseas missionaries dispatched by Ōtani Kōzui introduced Jōdo Shinshū to the Japanese concession in Tianjin. This sect became the main religion of the Japanese residents there, responsible for most of their funerary affairs. Its religious facility was the Tianjin branch temple of the Higashi Honganji (Jōdo Shinshū Ōtani-ha).[54]: 351

In April 1936, the Tianjin Buddhist Association was established inside the Honganji temple. Its members included six temples set up in the Japanese concession: the Tianjin branch of Higashi Honganji, the Nishi Honganji, Tianjin Sōtō Zen Kannonji, Nichiren Myōhōji, Shingon Kongōji of Mount Kōya, and Jōdo Chion-in Tianjin temple. In 1937, after Japan's full-scale invasion of China, various Japanese Buddhist sects called on both clergy and laity to support the war effort,[16] and during the battles for Tianjin, missionary monks of Nishi Honganji even took part directly. During the Japanese occupation, only Japanese Buddhist sects were allowed to operate openly in Tianjin, while local Chinese Buddhist associations were suppressed, resuming only after Japan's defeat.[55] After the war, the war responsibility of Japanese Buddhist sects such as Jōdo Shinshū—due to their assistance or direct participation in the war—drew the attention of scholars in both China and Japan.[16][56]

In 1903, the Japanese Christian Church began its activities in Tianjin.[17] For a long time, the Japanese church only ministered to Japanese expatriates. After the outbreak of the Pacific War, the Japanese army and church took over the properties of British and American churches, including hospitals and schools, and sent Western missionaries and expatriates into the Weihsien Internment Camp in Shandong.[21] Figures such as Amemiya Tatsumi, head of the Japanese Army Special Service Agency in Tianjin, used missionaries like Nakamura Saburō to control the local Chinese Christian Church, requiring it to align with the Japanese government.[57] Consequently, the behavior and responsibility of the Japanese Christian Church during the war became a subject of attention for scholars in both China and Japan.[17][58][59] In March 1967, the United Church of Christ in Japan officially acknowledged and repented for its support and participation in the war of aggression against China.[60]

Japanese Shinto entered the Tianjin Japanese concession along with Japanese residents. In 1915, the Japanese Residents' Association in Tianjin decided to establish the Tianjin Shrine in Daiwa Park to commemorate the enthronement ceremony of Emperor Taishō. Due to flooding, construction was delayed, and the shrine was not officially completed until 1920.[61] The Tianjin Inari Shrine was founded on April 27, 1926, on Fushimi Street, but no longer exists. Kanagawa University researcher Inamiya Yasuto has suggested that the shrine was probably established by Japanese expatriates originally from the Fushimi area of Kyoto, to enshrine the Inari deity.[62]

Life of the Expatriate Community

[edit]

Within the Japanese concession in Tianjin, Japanese expatriates attempted to construct a localized living space that allowed them to maintain a lifestyle similar to that of their homeland.[11] Consequently, their social life and leisure activities were strongly influenced by Japanese culture.[11]

In the early period of the Tianjin Japanese concession, Japanese residents often wore kimono and geta, which drew ridicule and criticism from Westerners and Chinese citizens, and also displeased the Consulate-General of Japan in Tianjin.[10] To standardize the expatriates’ image, in 1909 the Japanese consulate issued a “Consulate Ordinance” stating that anyone dressed inappropriately in public could be detained or fined, and recommended that men wear Western-style suits for formal occasions, while women should wear Western or Chinese attire.[10] In 1917, the consulate issued another notice prohibiting Japanese expatriates from wearing clothing that exposed their ankles in public, requiring women to wear socks to cover their ankles. Thereafter, restrictions on public attire were gradually strengthened, including bans on wearing geta and kimono in public.[10] As a result, Japanese residents in Tianjin generally switched to Western suits, wearing kimono only during major Japanese festivals.[10]

The cultural life of Japanese expatriates focused on reading Japanese books and periodicals, for which they established libraries.[11] In addition, they organized various traditional entertainment activities. Naniwa-za was the only Japanese theater in Tianjin, with stage and audience seating designed in Japanese style, regularly hosting performers invited from Japan or the Manchukuo region, including actors, comic storytelling, lectures, and festival performances.[11] Naoya Furuno, who once served as a pilot in the Japanese army, described the scene in his book: “Along the Baihe River in Tianjin, Japanese bars and cafes were adorned with neon lights, playing records of Tokyo Ondo and Kaikouji Ondo.”.[30]: 201 In 1941, the Tianjin branch of the Japanese Budo Association built the Budo Hall as a place for Japanese military personnel and expatriates to practice martial arts and physical fitness.[54]: 351

It was common for households in foreign concessions in Tianjin to employ Chinese servants, and Japanese residents were no exception. Masao Matsumoto, who taught at an elementary school in Tianjin, recalled: “At that time, almost every teacher’s household employed Chinese boys and women”.[63]: 14 Hisashi Kondo, who spent his childhood in Tianjin, also wrote in his memoir: “A Chinese servant family of three generations all worked in my household”.[64]: 177

Entertainment and the Sex Industry

[edit]

The exact time when the first Japanese geisha or prostitute appeared in Tianjin cannot be verified, but records indicate that as early as 1884, Japanese geisha and prostitutes were already active in the city.[65] In 1904, the Tianjin Japanese Concession Administration designated Asahi Street (now Nenjiang Road) as a “red-light district”.[65] In 1905, Tianjin established a specialized Geisha Management Office, responsible for supervising geisha and related activities in the area.[65] At the same time, a new “special license tax” was introduced, later renamed the “miscellaneous tax,” levied on geisha, barmaids, restaurants, and permanent or temporary performances, becoming an important source of revenue for the Tianjin Japanese Concession.[66]

By 1906, all Japanese restaurants in Tianjin were concentrated on Asahi Street. From the late Qing to the early Republican period, the number of prostitutes in the Tianjin Japanese Concession increased steadily.[67] By 1936, the Tianjin Japanese Concession had more than 200 licensed Japanese, Korean, and Chinese brothels, with over 1,000 officially operating and tax-paying prostitutes.[67] In 1937, when the Japanese army occupied Tianjin, they established a brothel across from the Sìmiàn Clock in the Japanese Concession, capturing women as “comfort women”.[68]

Public Health and Medical Services

[edit]At the initial stage of the Tianjin Japanese Concession, no medical or health institutions were established. After a cholera outbreak occurred in Tianjin in 1902, the Japanese Consul General Ijūin Hikoji collaborated with like-minded individuals to found the Kyōritsu Hospital, initially as a private hospital. In 1909, it was converted into a public hospital, managed by the Health Department under the Japanese Residents' Association in Tianjin, responsible for public health and the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases within the Japanese concession.[10]

In addition, within the Japanese concession there were Inoue Hospital, Tongren Hospital, Qianqiu Hospital, Zhonghe Hospital, Airen Hospital, Shiotani Hospital, and specialized dental clinics.[10] The number of hospitals in the concession had already exceeded the needs of the Japanese residents.[69]: 71 During the war in 1937, when Japanese troops invaded Tianjin and medical teams had not yet arrived, some prostitutes in the Japanese concession temporarily undertook urgently needed nursing tasks.[65]

The Japanese concession implemented relatively strict health management regulations, which also influenced the Chinese government's public health administration to some extent.[70]: 202 American scholar Ruth Rogaski noted that the Qing Dynasty's first municipal-level health bureau was established in Tianjin in 1902, reflecting the influence of Japanese (and German) models of modern hygiene on China.[70] From the perspective of health management, the Japanese concession may have been one of the most comprehensively supervised areas in Tianjin.[70]: 284 After the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, Japanese forces also occupied hospitals under the Anglo-American church system.[21]

Drug Trade

[edit]

In 1898, the Japanese consul in Tianjin indicated that 70% of the Japanese residents in Tianjin were engaged in the trade of prohibited substances such as morphine, and almost all pharmacies, restaurants, and general stores were involved in drug transactions.[7] In 1913, at a meeting of the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association, it was noted that drug trafficking activities had gradually shifted from the French Concession to the Japanese Concession. According to an investigation by Japanese Kwantung government official Fujiwara Tetsutaro, by the early 1920s, over 70 smoking houses had been established in the Tianjin Japanese Concession, and nearly 100 shops sold tobacco, with approximately 70% of Japanese residents involved in the drug trade.

Although the Consulate-General of Japan in Tianjin repeatedly expressed intentions to combat drugs, in practice it not only tolerated but also participated in the trade, allowing smoking houses to operate through the collection of “public welfare fees” and bribery mechanisms. During the postwar period of financial difficulty, the authorities even experimented with a smoking-house system, openly taxing hotels run by Chinese residents, which exacerbated drug proliferation. The drug economy formed a black market chain linking the resident association, the Green Gang, the police, and unscrupulous Japanese individuals. In 1917, the Yishi Bao revealed that although morphine was ostensibly banned in the Japanese Concession, a morphine company managed unified sales, yielding even greater profits than before.[71]: 1532

By the 1930s, drug trafficking in the Japanese Concession continued to expand. In September 1933 alone, 73 Japanese residents had been confirmed as drug addicts, though the actual number was far higher. Drugs circulating in the concession included not only opium but also processed substances such as morphine and heroin, with related facilities directly managed by military intelligence agencies. Asahi Street within the Tianjin Japanese Concession became a core area for drugs, with some pharmacies and trading companies superficially selling daily necessities while actually manufacturing and selling drugs. According to anti-drug organizations' investigations, by 1937 there were 248 trading companies in the Japanese Concession selling morphine and heroin, 137 smoking houses and tobacco shops, and numerous secret drug sites hidden in residential areas. Not only Japanese residents but also some military personnel were involved in the drug trade.[1]: 73

After the Japanese army gained control of North China, Tianjin became a key hub for transporting drugs from Persia, Japan, and Manchukuo. Although Japanese media occasionally reported on drug cases, details were sparse. In 1937, John Benjamin Powell, chief editor of the Miller's Review of the Far East, visited Tianjin and noted that many streets in the Japanese Concession had effectively become heroin trafficking zones, with drug factories disguised as residences. Despite the Chinese government's strict measures, including executing captured drug dealers, the results were limited.[7]

Research and Architectural Remains

[edit]Academic Research

[edit]

Research on the Japanese concessions in China mainly focuses on their establishment, expansion, and the process by which China reclaimed these concessions, closely linked with Japan's invasion of China. Among the six Japanese concessions in China, scholarly attention has been most concentrated on the Tianjin Japanese Concession.[72] The research covers topics such as public opinion responses, diplomatic negotiations, and, in the context of Chinese resistance to Japanese aggression, the political and legal systems of the concessions, related incidents of Japanese invasion, and social issues, all of which have drawn scholarly attention.[72]

Zhang Limin, a researcher at the Institute of Historical Studies of the Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences, believes that Japan was able to successfully establish a Japanese concession in Tianjin partly because it had prepared a detailed demarcation plan in advance and adopted a tough and coercive diplomatic strategy.[73] On the other hand, the Chinese government was in a passive position during the negotiations and adopted a stance of compromise and concession.[73] In particular, some Chinese officials displayed ambiguous attitudes, proactively made concessions, and even engaged in misleading superiors, providing opportunities for Japan.[73] Nevertheless, the establishment of the Tianjin Japanese Concession still took two years, during which two rounds of formal negotiations were held before a final agreement was reached.[73]

Surviving Architecture

[edit]

Since 1949, successive urban plans in Tianjin have not included these areas within the scope of historical and cultural heritage protection, instead treating them as ordinary urban development zones. This has resulted in irreparable losses to many historically valuable streets and buildings.[74] Some properties in the former Tianjin Japanese Concession were converted to public ownership; government agencies and state-owned enterprises moved in for office use, while ordinary residents were allocated housing in the former concession buildings. Located in the city center, the historical blocks of the former Tianjin Japanese Concession retain six buildings with key and special protection status, holding considerable historical value and urban memory.[41]

Influenced by Japanese modern urban planning concepts, the overall street pattern of this district shows the characteristics of “narrow streets and dense networks.” Streets are compact, and spatial layouts are precise. Existing buildings in the district mostly consist of two- to three-story alley houses built during the Japanese concession period, along with four- to five-story residences constructed after 1949, which have now aged. The combination of narrow streets and old buildings forms a distinctive urban atmosphere.[41]

Although located in the city center, this area has long been neglected and the streets show signs of decline. In recent years, with the rapid development of surrounding modern commerce and rising land prices, some streets have been replaced by large commercial, office, and residential projects, damaging the original street patterns and historical spatial structure.[41] The architectural styles within the district are complex and diverse, encompassing Japanese-style buildings, Republican-era buildings, Western-style buildings, and representative early PRC-era structures, with overall quality varying widely. Many historical buildings suffer from structural damage, material spalling, and other safety hazards due to long-term neglect, and some courtyards have been altered with unauthorized constructions.[41]

Following industrial restructuring in Tianjin during the 1990s, traditional industries declined, closed, or relocated, and all industrial relics within the former Japanese Concession have been demolished and no longer exist.[13]

In 2006, Tianjin's published "Master Plan of Tianjin City (2005-2020)" explicitly designated the area centered on Anshan Road—enclosed by Duolun Road, Shaanxi Road, Wanquan Road, Nanjing Road, Siping Road, and Xinhua Road—as the Anshan Road Historical and Cultural Protection Area.[74] This marked the first time since 1949 that the Tianjin master plan paid attention to the historical streets of the Japanese Concession. Although the protected area was limited, it represented a positive turn for the conservation of the Tianjin Japanese Concession.[74]

In 2011, Tianjin published protection plans for the first batch of 13 historical and cultural streets, including Jiefang North Road. Within the former Tianjin Japanese Concession, only a small area centered on Anshan Road Anshan Road Historical and Cultural Block was included in the historical façade protection scope.[75] This area preserves important historical buildings such as Butokuden, Jing Garden, Zhang Garden, Huiwen Middle School, and Former Residence of Duan Qirui. However, these buildings alone cannot fully represent the overall living environment of the Japanese Concession.[74] In contrast, the long-neglected alleys and lanes more accurately reflect the social life and residential conditions of Japanese Concession residents, holding important value for studying urban social history during the concession period.[74] Other historical façade buildings lack systematic protection.[41]

Meanwhile, some buildings in the district have undergone exterior renovation, but the work often failed to respect historical context and façade characteristics, relying instead on uniform paint, which damaged the original architectural style and sometimes made it irrecoverable, causing severe cultural heritage loss.[41] Moreover, many historically valuable buildings remain abandoned or vacant; some have owners, but due to long-term neglect, they have been uninhabited for years.[41]

See also

[edit]- Foreign concessions in Tianjin

- Foreign concessions in China

- Map of concessions in Tianjin (in Chinese)

- Japan Empire

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tetsurō Yagi (1997). A Japanese Boy in Tianjin (in Japanese). Tokyo: Soshisha. ISBN 9784794207913.

- ^ a b c d e f g 天津市地方志编修委员会 (1996). 天津通志·附志·租界 [Real Estate Records of Tianjin] (in Chinese). 天津: 天津社会科学院出版社. ISBN 9787805635736.

- ^ a b c d 李政; 周利成 (2015). "出宫到出走:天津事变中的溥仪" [From Leaving the Palace to Departure: Puyi during the Tianjin Incident]. 档案春秋 (12): 45–47. ISSN 1005-7501.

- ^ a b 刘敬坤; 邓春阳 (2000-03-30). "关于我国近代租界的几个问题" [Several Issues on China's Modern Concessions]. 南京大学学报:哲学人文社科版 (in Chinese) (2000(06)): 22–31.

- ^ Fei Chengkang (1992). History of Concessions in China (in Chinese). Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press. ISBN 7-80515649-2.

- ^ a b c d e 王铁崖 (1957). 中外旧约章汇编(第一册) (in Chinese). 三联书店.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as 万鲁建 (2010-06-03). 近代天津日本侨民研究 (PhD thesis) (in Chinese). 南开大学.

- ^ 天津市档案馆; 南开大学分校档案系, eds. (1992). 天津租界档案选编 (in Chinese). 天津: 天津人民出版社. ISBN 7201005448.

- ^ a b c 靳佳萍; 万鲁健 (2016-07-16). "试论郑永昌与天津日租界的设立与经营——基于日本外交档案的考察". 历史教学 (in Chinese) (2016(14)): 54–69.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l 王南南 (2015-05-01). 天津日本租界研究(1898-1945) [Research on the Japanese Concession in Tianjin (1898–1945)] (硕士 thesis). 南京大学.

- ^ a b c d e f 万鲁建 (2014-09-15). "试论天津日租界的"殖民空间"" [On the “Colonial Space” of the Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 东北亚学刊 (2014(05)): 50–55. doi:10.19498/j.cnki.dbyxk.2014.05.013.

- ^ Japanese Residents' Association, ed. (1913). Minutes of the Residents' Assembly in Taisho 2. Tianjin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Lan Xu; Zhao Xiaoyan (2009-09-20). "A Survey of Modern Industrial Relics in the Former Japanese Concession". China Light Industry Education (2009 (03)): 30–33.

- ^ a b c Zhang Hao; Park Hong-yeon (2018-06-15). "From the Hu–Bai Incident to the He–Mei Agreement: Chiang Kai-shek's Handling of the North China Incident". Studies on the War of Resistance Against Japan (2018 (02)): 107–124. ISSN 1002-9575.

- ^ a b Kang Tianjin (1999). Editorial Committee of the Tianjin Real Estate Chronicle (ed.). Tianjin Real Estate Chronicle. Tianjin: Tianjin Academy of Social Sciences Press. ISBN 7805637830.

- ^ a b c 忻平 (2001-09-15). "日本佛教的战争责任研究" [Research on the War Responsibility of Japanese Buddhism]. 华东师范大学学报(哲学社会科学版) (2001 (05)): 70–90+219. doi:10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5579.2001.05.006.

- ^ a b c 徐炳三 (2009-02-26). "日本基督教会战争责任初探" [A Preliminary Study on the War Responsibility of the Japanese Christian Church]. 抗日战争研究 (2009 (01)): 34–40.

- ^ Wang Ruoran; Lü Zhichen; Nobuo Aoki; Xu Subin (2023-05-20). "The Spatial Evolution and Development Strategies of Foreign Firms in Modern Tianjin". Historical Geography Research (2023–2). ISSN 2096-6822.

- ^ a b c Fu Min (2009-03-01). "Britain's Dual Diplomacy in the Far East and the Tianjin Concession Crisis". Republican Archives. ISSN 1000-4491.

- ^ Shigemitsu Mamoru (1982). Translation Committee of the Tianjin CPPCC (ed.). Diplomatic Memoirs of Shigemitsu Mamoru. Knowledge Press.

- ^ a b c 中国人民政治协商会议天津市委员会文史资料研究委员会, ed. (1982). 天津文史资料选辑 第21辑 [Selections of Tianjin Historical Materials, Vol. 21]. 天津: 天津人民出版社. pp. 164–184.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 谭汝为 (2015-10-14). "天津日租界街名沧桑" [The Vicissitudes of Street Names in the Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 天津市社会主义学院学报 (2015(3)): 51–53. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-4089.2015.03.013.

- ^ 天津市和平区地方志编修委员会 (2004-12-01). 和平区志(下册) [Gazetteer of Heping District (Vol. II)]. 天津: 中华书局. ISBN 7101044956.

- ^ "日本驻天津总领事馆——执行侵华政策、控制华北的中枢" [Consulate General of Japan in Tianjin—A hub for enforcing Japan's invasion policy and controlling North China]. 2011-10-28. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 2025-09-13.

- ^ a b c d 天津市地方志编修委员会, ed. (2001). 天津通志·公安志 [General Gazetteer of Tianjin: Public Security Records]. 天津: 天津人民出版社. ISBN 9787201036861.

- ^ a b 李洪锡 (2024-01-27). "近代日本外务省警察在华侵略活动研究" [Research on the Aggressive Activities of the Modern Japanese Foreign Ministry Police in China]. 近代史研究 (2024 (01)): 66–83+159. ISSN 1001-6708.

- ^ a b c 天津图书馆, ed. (2006). 天津日本租界居留民团资料 [Records of the Japanese Residents’ Association in the Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 南宁: 广西师范大学出版社. ISBN 7563359796.

- ^ 昭和五年共益会事务报告书 [Kyōeki-kai Activity Report, Showa 5] (in Japanese). 天津: 財団法人天津共益会. 1930.

- ^ a b c 张宗平 (1998-05-15). "日本中国驻屯军的由来、演变及罪行" [Origins, Evolution, and Crimes of the Japanese Garrison in China]. 北京社会科学 (1998 (02)): 73–80.

- ^ a b c d 古野直也 (1989). "天津军司令部 1901-1937" [Tianjin Military Command 1901–1937]. 国書刊行会 (in Japanese). ISBN 978-4336022950.

- ^ 西村正邦 (2002). 天津的柳絮 [Willow Fluff of Tianjin]. 非卖品.

- ^ a b c d e f g 吴弘明 (2006). 津海关贸易年报 (1865-1946) [Tianjin Customs Trade Reports (1865–1946)]. 天津: 天津社会科学院出版社. ISBN 9787806882320.

- ^ 东亚同文会, ed. (1959). 对华回忆录 [Memoirs on China]. Translated by 胡锡年. 商务印书馆.

- ^ a b 中国驻屯军司令部, ed. (1986). 二十世纪初的天津概况 [Overview of Tianjin in the Early Twentieth Century]. Translated by 侯振彤. 天津市地方史志编修委员会总编辑室.

- ^ 李正华 (1991-03-02). ""九·一八事变"至"七·七事变"期间日本在华北走私述略" [A Brief Account of Japanese Smuggling in North China from the “September 18 Incident” to the “July 7 Incident”]. 云南教育学院学报 (1): 55–58. ISSN 1672-1306.

- ^ 张利民 (2009). "20世纪30年代前天津日侨社会与特征" [The Japanese Community in Tianjin and Its Characteristics before the 1930s]. 历史档案 (4): 105–111. ISSN 1001-7755.

- ^ 外务省史料馆 (1999). 外务省警察史 第34卷(支那之部一北支) [History of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Police, Vol. 34 (China, North China Section)] (in Japanese). 东京都: 不二出版.

- ^ 外务省通商局, ed. (1919). 在支那本邦人进势概览 (第二回) [Overview of Japanese Expansion in China (Vol. 2)] (in Japanese).

- ^ 外务省通商局, ed. (1992). 通商类纂 [Compendium of Commerce] (in Japanese). Vol. 173. Tokyo: 不二出版.

- ^ 李竞能, ed. (1990). 天津人口史 [Population History of Tianjin]. 南开大学出版社. ISBN 9787310002689.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 赵禹舒 (2019-05-01). 触媒视角下天津原日租界历史街区更新策略探究 [Research on Renewal Strategies for Historical Districts of the Former Tianjin Japanese Concession from a Catalytic Perspective] (硕士 thesis). 天津大学.

- ^ a b c 邓婧蓉; 青木信夫; 郑颖 (2016). "天津原日租界区结果形态研究" [Study on the Resulting Morphology of the Former Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 建筑与文化 (2): 86–88.

- ^ 孙媛 (2019-04-15). "近代天津日租界大和公园的建设背景及造园特点" [Construction Background and Garden Features of Yamato Park in the Modern Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 装饰 (2019 (04)): 88–90. doi:10.16272/j.cnki.cn11-1392/j.2019.04.018.

- ^ 日本居留民团, ed. (1928). 昭和三年天津日本居留民团事务报告书 [Report of the Japanese Residents' Association in Tianjin, Showa 3] (in Japanese). 天津: 天津日本居留民团.

- ^ a b c d 孙媛 (2019-05-10). "近代天津日租界大和公园区域空间规划及景观元素研究" [Spatial Planning and Landscape Elements of Yamato Park in the Modern Tianjin Japanese Concession]. 中国园林 (35 (05)): 140–144. doi:10.19775/j.cla.2019.05.0140.

- ^ a b c 曹牧 (2023-07-27). "近代天津排水系统的变化与生态影响" [Changes in Tianjin’s Modern Drainage System and Its Ecological Impact]. 近代史研究 (2023 (04)): 27–44+160. ISSN 1001-6708.

- ^ a b c d 隈元实道 (1901). 日出学馆记事 [Records of the Nichiritsu Gakkan] (in Japanese). 东京: 静思馆.

- ^ 清国驻屯军司令部, ed. (1909). 天津志 [Gazetteer of Tianjin] (in Japanese). 东京: 博文馆.

- ^ 万鲁建 (2009). "近代日本在天津设立的学校" [Schools Established by Modern Japan in Tianjin]. 消费导刊 (16): 228–229. ISSN 1672-5719.

- ^ 吴艳 (2013-11-15). "清末民初天津日本租界的初等教育一考——以日出学馆为例" [A Study of Primary Education in the Japanese Concession of Tianjin during the Late Qing and Early Republic of China: The Case of Nichiritsu Gakkan]. 河北大学学报(哲学社会科学版) (2013(06)): 112–116. ISSN 1005-6378.

- ^ 臼井忠三 (1941). 天津居留民团三十周年纪念志 [Commemorative History of the 30th Anniversary of the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association] (in Japanese). 天津居留民团.

- ^ 南开大学日本研究院, ed. (2008). 日本研究论集2008 [Collected Papers on Japanese Studies 2008]. 天津: 天津人民出版社. ISBN 9787201060989.

- ^ 忻平 (1999-03-25). "近代日本佛教净土真宗东西本愿寺派在华传教述论" [On the Missionary Activities of the Jōdo Shinshū Higashi and Nishi Honganji Sects in Modern China]. 近代史研究 (1999 (02)): 255–269. ISSN 1001-6708.

- ^ a b 陈灿文; 何铁冰 (1998). 和平区地名志编纂委员会 (ed.). 天津市地名志·和平区 [Gazetteer of Place Names of Tianjin: Heping District]. 天津人民出版社. ISBN 7-201-02086-2.

- ^ 濮文起; 莫振良 (2004-06-15). "天津宗教的历史与现状" [The History and Current Situation of Religion in Tianjin]. 世界宗教研究 (2004 (02)): 98–107. ISSN 1000-4289.

- ^ 菱木政晴 (1993). 浄土真宗の戦争責任 [The War Responsibility of Jōdo Shinshū] (in Japanese). 东京: 岩波書店. ISBN 9784000032438.

- ^ 姚洪卓 (1990-04-01). "日本侵华战争中对宗教的利用" [The Use of Religion during Japan's Invasion of China]. 历史教学问题 (1990 (03)): 58–59+62.

- ^ 渡辺祐子 (2014). "Japanese Studies on Christian History in China, with a focus on the period from 1937 to 1945". Asian Christian Review (7): 46–57.

- ^ 高新慧 (2019-12-09). "渡边祐子:日本的基督教会是如何协助发动战争的" [Watanabe Yuko: How the Japanese Christian Church Assisted in Waging War]. 澎湃新闻.

- ^ 鈴木正久 (1967-03-26). 第二次大戦下における日本基督教団の責任についての告白 [Confession Regarding the Responsibility of the United Church of Christ in Japan during World War II] (Speech). 1967年复活节主日 (in Japanese). 东京: 日本基督教団. Retrieved 2025-04-18.

- ^ 岩下傳四郎 (1941). 大陸神社大観 [General Survey of Shrines on the Continent]. 京城(Seoul today): 大陸神道聯盟. p. 506.

- ^ 稲宮康人. "中国・華北(北京、天津、済南、煙台、青島)の神社跡地" [The Remains of Shrines in North China (Beijing, Tianjin, Jinan, Yantai, Qingdao)] (PDF) (in Japanese). Kanagawa University. Retrieved 2025-04-15.

- ^ 松本正雄 (1973). 誰も忘れられない──私と中国及び中国人 [No One Can Forget: Myself, China, and the Chinese] (in Japanese). 象文社.

- ^ 近藤久义 (2005). 天津を愛して百年: そして子々孫々 [A Century Loving Tianjin: And Generations After] (in Japanese). 新生出版. ISBN 9784861280795.

- ^ a b c d 李炜; 万鲁建 (2016-09-01). "近代天津的日本"特殊职业女性"" [Japanese “Special Occupation Women” in Modern Tianjin]. 城市史研究(第35辑): 213–243.

- ^ 日本居留民团 (1910). 明治四十二年天津日本居留民团事务报告书 [Report of the Tianjin Japanese Residents' Association, Meiji 42] (in Japanese). 天津: 日本居留民团.

- ^ a b 江沛 (2003-03-27). "20世纪上半叶天津娼业结构述论" [On the Structure of the Prostitution Industry in Tianjin in the First Half of the 20th Century]. 近代史研究 (2003 (02)): 153–186. ISSN 1001-6708.

- ^ 魏宏运 (2014-04-16). "沈从文:1937年北平沦陷的一天" [Shen Congwen: The Day Beiping Fell in 1937]. 历史教学(下半月刊) (2014 (04)): 64–70.

- ^ 外务省警察史 [History of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Police] (in Japanese). Vol. 第34巻(支那之部——北支). 东京: 不二出版社. 1999.

- ^ a b c 罗芙芸. 卫生的现代性:中国通商口岸卫生与疾病的含义 [The Modernity of Hygiene: Public Health and Disease at Chinese Treaty Ports]. 南京: 江苏人民出版. ISBN 9787214047168.