Huainanzi

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (February 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Huainanzi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Qing-era copy of Huainanzi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 淮南子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | [The Writings of] the Huainan Masters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

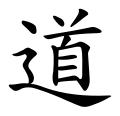

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

The Huainanzi is an ancient philosphical and governmental[1] Chinese text made up of essays from scholarly debates held at the court of Liu An, Prince of Huainan, before 139 BCE. Compiled as a handbook for an enlightened sovereign and his court, the work attempts to define the conditions for a perfect socio-political order, derived mainly from a perfect ruler.[2] With a notable Zhuangzi 'Taoist' influence, alongside Chinese folk theories of yin and yang and Wu Xing, the Huainanzi draws on Taoist, Legalist, Confucian, and Mohist concepts, but subverts the latter three in favor of a less active ruler, as prominent in the early Han dynasty before the Emperor Wu.[3]

The early Han authors of the Huainanzi likely did not yet call themselves Taoist, and differ from Taoism as later understood.[4] But K.C. Hsiao and the work's modern translators still considered it a 'principal' example of Han 'Taoism', retrospectively.[5] Although the Confucians classified the text as Syncretist (Zajia), its ideas theoretically contributed to the later founding of the Taoist church in 184 c.e.[6] Sima Tan may have even had the "subversive 'syncretism'" of the Huainanzi in mind when he coined the term Daojia ("Taoism"), claiming to "pick what is good among the Confucians and Mohists."[7]

Dating

[edit]Said to have been compiled for presentation to the Emperor Wu of Han, while the modern translators of the Huainanzi did believe it had been compiled by a Liu An, they believed much of its material had earlier been written during the reign of Wu's father, Emperor Jing of Han, under whome debates on organization of the government had already begun. Liu An himself would have been around during Jing's reign, and the process of debate and organization were not quick; although increasing under Jing, they date back to the founding of the Han dynasty.[8]

The work

[edit]Scholars are reasonably certain regarding the date of composition for the Huainanzi. Both the Book of Han and Records of the Grand Historian record that when Liu An paid a state visit to his nephew the Emperor Wu of Han in 139 BC, he presented a copy of his "recently completed" book in twenty-one chapters. Recent research shows that Chapters 1, 2, and 21 of the Huainanzi were performed at the imperial court.[9]

The Huainanzi is an eclectic compilation of chapters or essays that range across topics of religion, history, astronomy, geography, philosophy, science, metaphysics, nature, and politics. It discusses many pre-Han schools of thought, especially the Huang–Lao form of religious Daoism, and contains more than 800 quotations from Chinese classics. The textual diversity is apparent from the chapter titles, listed under the table of contents (tr. Le Blanc, 1985, 15–16).

Some passages are philosophically significant, with one example combining Five Phase and Daoist themes.

When the lute-tuner strikes the kung note [on one instrument], the kung note [on the other instrument] responds: when he plucks the chiao note [on one instrument], the chiao note [on the other instrument] vibrates. This results from having corresponding musical notes in mutual harmony. Now, [let us assume that] someone changes the tuning of one string in such a way that it does not match any of the five notes, and by striking it sets all twenty-five strings resonating. In this case there has as yet been no differentiation as regards sound; it just happens that that [sound] which governs all musical notes has been evoked.

Thus, he who is merged with Supreme Harmony is beclouded as if dead-drunk, and drifts about in its midst in sweet contentment, unaware how he came there; engulfed in pure delight as he sinks to the depths; benumbed as he reaches the end, he is as if he had not yet begun to emerge from his origin. This is called the Great Merging. (chapter 6, tr. Le Blanc 1985:138)

Major influences

[edit]Alongside the Tao Te Ching (Laozi) and Zhuangzi,[10] the Huainanzi includes influences from such works as the Classic of Poetry, Book of Changes, Book of Documents, Han Feizi, Guanzi, Mozi, Lüshi Chunqiu, Chu Ci, and the Classic of Mountains and Seas.[10] It is mainly chapter 12 that draws on a combination of Confucian texts, the Lunyu (Analects), Mencius, Xunzi, and Zisizi.[10] Scattered anecdotes are comparable to Mencius, though sometimes differing.[11]

The first, second and twelfth chapters of the work are based on the Laozi,[12] with Chapter's 2 title "Activating the Genuine" referring to the Dao.[13] But in the evaluation of the Huainanzi's modern editors, the Huainanzi most strongly resonates with the Zhuangzi.[14] All of Chapter 2's primary themes draw on the Zhuangzi, with one section drawing on such classic Inner Zhuangzi imagery as the "Great Clod" representing Earth (and the Dao), and "The Butterfly Dream".[13]

Quantitatively, the Huainanzi's most major influences are the Zhuangzi (269 references) and encyclopedic Lüshi Chunqiu (190), with the Lüshi Chunqiu quoted in twenty of the Huainanzi's twenty one chapters. Most prominently influencing chapters 3-5, much of chapter five quotes directly from the Lushi Chunqiu's first twelve chapters. The Huainanzi's second most major influences are drawn from the Tao Te Ching (99) and Han Feizi (72), or a bit less than half as much, including traces of the Han Feizi's predecessor Shen Buhai.[15]

But the work disparages the Han Feizi's combination of Shang Yang and Shen Buhai, glossing them together as penal (Shen Buhai was not evidently penal).[16] One section briefly re-frames a story from the Han Feizi, adding Laozi, Confucius and Han Fei as characters. Confucius is used as approving Laozi leniency ("to attract those who would admonish (the ruler"), while Han Fei decries what he takes to be a failure to punish the officials as abandoning ritual.[17]

Zhuangzi influences only existed as traces in the earlier, late Warring States period Han Feizi,[18] and the Mawangdui silk texts Huangdi sijing, entombed in the early Han dynasty, still did not associate Laozi and Zhuangzi together.[19] In these terms, the Huainanzi is notable as the main evidence of Zhuangzi influence in the Han dynasty.[20]

Reformist conservatism

[edit]If Dong Zhongshu was familiar with the Huainanzi, its "syncretism" would likely have infuriated him, deciding for itself the relation between fundamental Confucian texts and relegating them to one quarter of the "fundamentals of rulership."[10] Though positively receiving earlier reunification of the empire, the Huainanzi opposed a growing expansion of centralized government, with its upcoming class of attending (Confucian) scholar-officials.

Not believing decentralization would win out, it sought to forge a "third way" between centralization and decentralization - with the interest of the local kingdoms in mind. To this end, it places heavenly prognosticators above (Confucian) ritual specialists, and advocates ideas of wuwei nonaction, recommending the ruler put aside trivial matters to abide in Pure Unity as Empty Nothingness. Aiming to demonstrate how every text before it is part of its own integral unity, the Huainanzi posed a threat to the Han court.[21]

When the First Emperor of Qin conquered the world, he feared that he would not be able to defend it. Thus, he attacked the Rong border tribes, repaired the Great Wall, constructed passes and bridges, erected barricades and barriers, equipped himself with post stations and charioteers, and dispatched troops to guard the borders of his empire. When, however, the house of Liu Bang took possession of the world, it was as easy as turning a weight in the palm of your hand.

In ancient times, King Wu of Zhou vanquished tyrant Djou... (and then) distributed the grain in the Juqiao granary, disbursed the wealth in the Deer Pavilion, destroyed the war drums and drumsticks, unbent his bows and cut their strings. He moved out of his palace and lived exposed to the wilds to demonstrate that life would be peaceful and simple. He lay down his waist sword and took up the breast tablet to demonstrate that he was free of enmity. As a consequence, the entire world sang his praises and rejoiced in his rule, while the Lords of the Land came bearing gifts of silk and seeking audiences with him. [His dynasty endured] for thirty-four generations without interruption.

Therefore, the Laozi says: "Those good at shutting use no bolts, yet what they shut cannot be opened; those good at tying use no cords, yet what they tie cannot be unfastened." Chapter 12.47[22]

Table of contents

[edit]| Number | Name | Reading | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 原道訓 | Yuandao | Searching out Dao (Tao) |

| 2 | 俶真訓 | Chuzhen | Beginning of Reality |

| 3 | 天文訓 | Tianwen | Patterns of Heaven |

| 4 | 墜形訓 | Zhuixing | Forms of Earth |

| 5 | 時則訓 | Shize | Seasonal Regulations |

| 6 | 覽冥訓 | Lanming | Peering into the Obscure |

| 7 | 精神訓 | Jingshen | Seminal Breath and Spirit |

| 8 | 本經訓 | Benjing | Fundamental Norm |

| 9 | 主術訓 | Zhushu | Craft of the Ruler |

| 10 | 繆稱訓 | Miucheng | On Erroneous Designations |

| 11 | 齊俗訓 | Qisu | Placing Customs on a Par |

| 12 | 道應訓 | Daoying | Responses of Dao |

| 13 | 氾論訓 | Fanlun | A Compendious Essay |

| 14 | 詮言訓 | Quanyan | An Explanatory Discourse |

| 15 | 兵略訓 | Binglue | On Military Strategy |

| 16 | 說山訓 | Shuoshan | Discourse on Mountains |

| 17 | 說林訓 | Shuolin | Discourse on Forests |

| 18 | 人間訓 | Renjian | In the World of Man |

| 19 | 脩務訓 | Youwu | Necessity of Training |

| 20 | 泰族訓 | Taizu | Grand Reunion |

| 21 | 要略 | Yaolue | Outline of the Essentials |

Notable translations

[edit]- Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah A.; Meyer, Andrew Seth; Roth, Harold D. (2010). The Huainanzi. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52085-0.

- Le Blanc, Charles; Mathieu, Rémi (2003). Philosophes Taoïstes II: Huainan zi (in French). Paris: Gallimard.

Translations that focus on individual chapters include:

- Balfour, Frederic H. (1884). Taoist Texts, Ethical, Political, and Speculative. London: Trübner.

- Morgan, Evan (1933). Tao, the Great Luminant: Essays from the Huai-nan-tzu. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

- Wallacker, Benjamin (1962). The Huai-nan-tzu, Book Eleven: Behavior Culture and the Cosmos. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

- Kusuyama, Haruki (1979–1988). E-nan-ji 淮南子 [Huainanzi]. Shinshaku kanbun taikei (in Japanese). Vol. 54, 55, 62.

- Larre, Claude (1982). Le Traité VIIe du Houai nan tseu: Les esprits légers et subtils animateurs de l'essence [Huainanzi Chapter 7 Translation: Light Spirits and Subtle Animators of Essence]. Variétés sinologiques (in French). Vol. 67.

- Ames, Roger T. (1983). The Art of Rulership: A Study in Ancient Chinese Political Thought. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Le Blanc, Charles (1985). Huai nan tzu; Philosophical Synthesis in Early Han Thought: The Idea of Resonance (Kan-ying) With a Translation and Analysis of Chapter Six. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Major, John S. (1993). Heaven and Earth in Early Han Thought: Chapters Three, Four and Five of the Huainanzi. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Ames, Roger T.; Lau, D.C. (1998). Yuan Dao: Tracing Dao to Its Source. New York: Ballantine Books.

Television series

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Major 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Le Blanc (1993), p. 189.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 104; Creel 1970, p. 101.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 91.

- ^ Liu 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Meyer 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Goldin 2005a, p. 111.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 1-2,5.

- ^ Wong, Peter Tsung Kei (2022). "The Soundscape of the Huainanzi 淮南子: Poetry, Performance, Philosophy, and Praxis in Early China". Early China. 45. Cambridge University Press: 515–539. doi:10.1017/eac.2022.6. ISSN 0362-5028. S2CID 252909236.

- ^ a b c d Major 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Major (2010), p. 327,467.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 27,78.

- ^ a b Major 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 26-27.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 26-27,34,230,487,762; Creel 1970, p. 101; Goldin 2005a.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 418.

- ^ Mair (2000), p. 33.

- ^ Graham (1989), p. 170.

- ^ Hansen 2024.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 4-5,25-26,34,487.

- ^ Major 2010, p. 474-475.

Sources

[edit]- Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1970). What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-12047-8.

- Graham, A.C. (1989). Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9942-5.

- Le Blanc, Charles (1993). "Huai nan tzu 淮南子". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute for East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 189–95. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Mair, Victor H. (2000). "The Zhuangzi and its Impact". In Kohn, Livia (ed.). Daoism Handbook. Leiden: Brill. pp. 30–52. ISBN 978-90-04-11208-7.

- (Goldin, Paul R. (2005a). "Insidious Syncretism in the Political Philosophy of Huainanzi". University of Hawai'i Press: 90–111.

- Major, John S. (2010). The Huainanzi A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52085-0.

- Hansen, Chad (2024). "Zhuangzi". In Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2024 ed.). Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- Liu, Xiaogan (2014). Xiaogan Liu (ed.). Dao Companion to Daoist Philosophy. Springer. ISBN 9789048129270.

- Meyer, Andrew Seth (2012). The Dao of the Military. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231153331.

External links

[edit]- 淮南子 - Chinese Text Project

- 淮南子, original text in Chinese 21 chapters

- 淮南子, original text in Chinese 21 chapters

- 淮南子, original text in Chinese 21 chapters

- Tao, the Great Luminant, Morgan's translation

- Huainan-zi, Sanderson Beck's article

- Huainanzi, Chinaknowledge article