History of the Finnish language

The Finnish language is a Finnic language spoken mostly in Finland that descends from Proto-Finnic and in turn from Proto-Uralic. It is closely related to the Estonian language as well as less-spoken languages, such as Karelian and Veps, and is also distantly related to Hungarian.

The history of the Finnish language can be divided into multiple eras. The earliest phase, Early Finnish (varhaissuomi), lasted from its separation from the other Finnic languages sometime around the end of the first millennium AD until 1540. Around this time, the first Finnish texts of note that survive were written, marking the start of the Old Literary Finnish (vanha kirjasuomi) period. This lasted until the early 19th century, when some time around 1810–1820, the development of the Finnish language entered a new phase called Early Modern Finnish (varhaisnykysuomi). This developed into Modern Finnish (nykysuomi) around the 1870s, by 1880 at the latest.

Origins

[edit]

Finnish belongs to the Uralic language family and more specifically to the Finnic branch of this family.[1] Thus, Finnish has developed from Proto-Finnic, which in turn has developed from Proto-Uralic. Neither Proto-Uralic nor Proto-Finnic was written down, and what is known of them has been derived through historical linguistics. This includes reconstructions, which are traditionally marked with an asterisk (*).

Finnish is noted for its conservatism.[2] Many of the features reconstructed to Proto-Uralic, such as an agglutinating morphology, vowel harmony, consonant gradation, invariably initial (primary) stress, and possessive suffixes,[3] are still present in Finnish today. Among the Finnic features that are not found in the other Uralic languages are adjective–noun agreement, the analytic perfect and pluperfect tenses, and possibly the default word order being SVO instead of SOV, although the Finnic word order was likely flexible, as in Finnish today.[4]

Proto-Uralic was originally spoken east of the Ural Mountains, but after its dispersal not long before the 2nd millennium BC, Uralic languages had reached as far west as the upper reaches of the rivers Volga and Oka.[5] Slightly after the beginning of the spread of Sámi languages (to southeastern Finland by around 1000 BC and to Central Scandinavia by 200 AD), the Finnic speakers then began to spread along the upper Oka,[6] and the main group reached the northern and western coasts of Estonia around 800 BC. Shortly thereafter, they also reached southwestern and southern Finland.[7] Development of Proto-Finnic into Late Proto-Finnic took place in Northern Estonia and spread across the gulf into southwestern and southern Finland in the Roman Iron Age,[8] marking a second arrival into Finland.[9] The speakers of the earlier Finnic varieties as well as the Sámi-speaking populations that had already settled the same area shifted their language to Late Proto-Finnic.[10] Subsequently, Late Proto-Finnic continued its expansion north of the Gulf of Finland, along the Kokemäenjoki river valley, reaching Tavastia and then east to Karelia by the 8th century AD and Savonia between the 8th and 11th centuries AD. Upon reaching Karelia, Finnic unity began to break down.[11] As they spread, the Finnic speakers assimilated the Sámi-speaking populations living inland, eventually leaving the Sámi languages in what was once their northwestern periphery.[12]

The breakup of the Finnic languages can also be studied linguistically. After South Estonian and Livonian branched off, the remaining core of the Finnic languages then split into Northern Finnic (including Finnish) and Central Finnic (including Estonian).[13] Western Finnish (the western dialects of Finnish) represents a separate node in the tree under Northern Finnic. Eastern Finnish (the eastern dialects), also under Northern Finnic, is more closely related to Karelian and Ingrian;[14] they share a common proto-language, known in literature as Proto-Karelian (muinaiskarjala).[15] Therefore, Finnish has effectively developed from two different (albeit closely related) languages melding into one.[16]

Among the sound and grammatical changes that can be noted from Late Proto-Finnic to North Proto-Finnic are (with Finnish reflexes):[13]

- *kt, *pt > *ht (*koktu > kohtu)

- the third-person singular verb ending *-pi (*anta-pi > dialectal antavi, modern standard antaa)

- *kc > *ks, *pc > *ps (*kakci > kaksi, *lapci > lapsi)

- *ck > *tk (*pucki > putki)

- *c > *s (*cika > sika, *keüci > köysi), except in *cc, *cr

- sporadic *ai > *ei (*haina > heinä, *raici > reisi)

- *ë (e.g. Estonian õ) > *e (*tërva > terva, *lainëh > laine)

- development of *ö in non-initial syllables under vowel harmony (*näko > näkö).

Estimates put the number of Finnish words inherited from Proto-Uralic at around 300–400; despite their small number, they make up approximately 70–80 percent of average speech.[17] Inherited words include nouns related to relatives, body parts, animals, and plants, along with many basic verbs[18] and most of the pronouns.

Loanwords

[edit]The oldest loanwords in Finnish were already present in Proto-Uralic, which borrowed words from Indo-Iranian languages.[19] Proto-Finnic has many loanwords from the Baltic (over 250 words), Germanic (over 500) and Slavic languages (perhaps over 100).[8] After Proto-Finnic, Finnish has borrowed extensively from Swedish, accounting for about a half of all loanwords in the language.[20] Furthermore, many words were also borrowed from Middle Low German, even without Swedish mediation.[21] More recently, English has become the most important source of new loanwords, as it has in the rest of the Western world.[22]

Loanwords in Finnish, both old and new, include:

| Finnish | Source | Comparandum |

|---|---|---|

| arvo "value" | Indo-Iranian | Ossetian аргъ arǧ[19] |

| jumala "god" | Sanskrit द्युमत् dyumát[19] | |

| kehrä "spindle" | Sanskrit चात्त्र cāttra[19] | |

| orja "slave" | Sanskrit आर्य ā́rya[19] | |

| piimä "cultured buttermilk" | Avestan 𐬞𐬀𐬉𐬨𐬀𐬥 paēman[19] | |

| sata "hundred" | Sanskrit शत śatá[19] | |

| vasara "hammer" | Sanskrit वज्र vájra[19] | |

| hammas "tooth" | Baltic | Lithuanian žambas[23] |

| heimo "tribe" | Lithuanian šeima[23] | |

| kaikki "all" | Lithuanian kiek[23] | |

| kaula "neck" | Latvian kakls[23] | |

| lohi "salmon" | Latvian lasis[23] | |

| morsian "bride" | Lithuanian martì[23] | |

| sisar "sister" | Lithuanian sesuo[23] | |

| armas "dear" | Germanic | Old Norse armr[23] |

| ja "and" | Gothic 𐌾𐌰𐌷 jah[23] | |

| kansa "people" | Gothic 𐌷𐌰𐌽𐍃𐌰 hansa[23] | |

| kuningas "king" | Old English cyning[23] | |

| leipä "bread" | Old Norse hleifr[23] | |

| rengas "hoop, ring" | Old Norse hringr[23] | |

| valta "power, might" | Icelandic vald[23] | |

| äiti "mother" | Gothic 𐌰𐌹𐌸𐌴𐌹 aiþei[23] | |

| ammatti "occupation" | Middle Low German[24] ambacht | |

| häät "wedding" | Middle Low German[24] hȫge | |

| kirkko "church" | Middle Low German[24] kirke | |

| rehti "honest" | Middle Low German[24] recht | |

| rouva "madam, lady" | Middle Low German[24] vrouwe | |

| housut "trousers" | Swedish hosa[23] | |

| kahvi "coffee" | Swedish kaffe[23] | |

| laki "law" | Swedish lag[23] | |

| sielu "soul" | Swedish själ[23] | |

| tuoli "chair" | Swedish stol[23] | |

| tyyny "pillow" | Swedish dyna[23] | |

| vihkiä "to consecrate" | Swedish viga[23] | |

| lusikka "spoon" | Old East Slavic лъжька lŭžĭka[23] | |

| risti "cross" | Old East Slavic крьстъ krĭstŭ[23] | |

| tavara "goods" | Russian товар tovar[23] | |

In a 2018 article, linguist Kaisa Häkkinen estimated that out of the vocabulary present in a learner's dictionary, 49 percent of words were native, 46 percent were loanwords, and the remaining five percent had a disputed etymology. Out of the native vocabulary, 45 percent were older than Proto-Finnic, 52 percent were from the Proto-Finnic era, and the remaining 3 percent from after Proto-Finnic.[25]

- Indo-European and Indo-Iranian loans (12%)

- Old Germanic loans (39%)

- Swedish and German (including Low German) loans (17%)

- Baltic loans (12%)

- Slavic loans (5%)

- Internationalisms (15%)

Early Finnish

[edit]Early Finnish represents the earliest period of the Finnish language as separate from the other Finnic languages. Its start date is placed around 700 AD.[26] Some sources distinguish between Early and Medieval Finnish, with a crossover point around 1200.[26] By 1000 AD, there were four well-defined dialect regions: Southwest Finland, Tavastia, Karelia and Savonia.[27] These belonged to two diachronically distinct language groups of Western and Eastern Finnish. Southwest Finland and Tavastia belonged to Western Finnish, while Savonia and Karelia belonged to Eastern Finnish. Early (and Medieval) Finnish covers the western dialects, while the eastern dialects instead developed as part of Proto-Karelian during this time.

For reference, today, there are seven dialectal groups: the Southwest Finnish dialects, the Tavastian dialects, the South Ostrobothnian dialect, the Central and North Ostrobothnian dialects, the Peräpohjola dialects, the Savonian dialects, and the South Karelian dialects; the first five comprise the western dialects, and the last two the eastern dialects.[28] The South Ostrobothnian dialect likely developed between the 9th and 12th centuries.[29] The more northern dialects (the Central and North Ostrobothnian dialects and the Peräpohjola dialects) tend to display a mix of western and eastern features due to Karelian influence.[30][31]

Written attestations of Early Finnish are scant, mostly consisting of individual names of both people and locations since at least the 13th century.[32] Even such fragmentary records are useful to understand the history of Early Finnish and can be used to help establish approximate dates for certain sound changes.[33]

Among the sound changes that can be noted during the Early Finnish period (including Medieval Finnish) are:[34]

- the spirantization of *b > *ꞵ (> v), *d > *ẟ (/ð/), *g > *ɣ

- likewise, in consonant clusters before voiced consonants, *k > *ɣ, *p > *ꞵ (> v), *t > *ẟ (/ð/)

- *cc > *θθ

- *cr > *θr > *hr

- the diphthongization of *ee > *ie, *oo > *uo, *öö > *üö

- semi-long consonants merging with short consonants (e.g. *k' > *k)[35]

Heikkilä (2016) lists more changes, some of which were regional:[33]

- loss of word-final *-k and their corresponding intervocalic *ɣ (seemingly early)

- vocalization of (original) *k, *p, *t in clusters before voiced consonants

- *eü > *öü, *iü > *üü (in initial syllables)

- *lẟ > *ll, *nẟ > *nn, *rẟ > *rr

- *mꞵ > *mm

- elision of intervocalic *h between unstressed syllables

Apocope, at least in certain inflected forms, likely began around the 14th century and rapidly gained ground in the 15th century.[36] Western Finnish dialects began to be clearly distinct in the Late Middle Ages, but nevertheless remained relatively uniform due to high mobility until the 16th century.[37]

Proto-Karelian, which yielded the Eastern Finnish dialects, is thought to have undergone the elision of intervocalic *-d-, *-g-, the development of the plural marker *-loi-, and the labialization of *e in non-initial syllables when followed by labial consonants.[38] Diphthongization of *ee, *oo, *öö had not yet occurred in Proto-Karelian, and instead spread from the western dialects to Eastern Finnish and to Karelian through the Savonian dialects after the breakup of Proto-Karelian.[39]

The earliest known full sentence in Finnish is dated to around 1450 and appears in a travel journal primarily written in German: Mÿnna thachton gernaſt ſpuho ſom̅en gelen Emyna daÿda. These words are ascribed to the Bishop of Turku at the time.[40] During Swedish rule in Finland (starting from the 1150s), Swedish was the language of administration,[41] while Latin was used in the church; Finnish was merely the language of the common people. However, the Bishopric of Turku was using Finnish in church service already since 1492, when it was decreed that at least the Lord's Prayer, Hail Mary and the creed had to be written down and read to the people in their own language. None such texts have survived.[42][43]

Old Literary Finnish

[edit]Mikael Agricola

[edit]

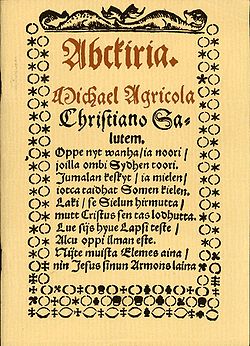

The period of Old Literary Finnish begins with the first known books to be printed in Finnish. They were written by Mikael Agricola, often referred to as the "father of Literary Finnish".[44] Agricola was a clergyman and a fluent speaker of both Swedish and Finnish. Under the Reformation period, both of the leading figures, Erasmus and Martin Luther, stressed that the word of God be accessible to the common people in their own language. After Luther's German translation of the Bible, Agricola set out to translate the Bible into Finnish.[45]

The first book was a primer written by Agricola called Abckiria, published in 1543. Today, it exists in complete form as a composite from multiple different editions.[44] The poem on the first page of Abckiria remains an enduring piece of Finnish literature even today:

| Oppe nyt wanha, ia noori / joilla ombi Sydhen toori / Jumalan keſkyt / ia mielen iotca taidhat Somen kielen. Laki / ſe Sielun hirmutta / mutt Criſtus ſen tas lodhutta. Lue ſijs hyue Lapſi teſte / Alcu oppi ilman eſte. Nijte muiſta Elemes aina / nin Jeſus ſinun Armons laina |

Learn now, old and young, |

Agricola completed translating the New Testament in 1548 but never fully translated the Old Testament due to a lack of funding.[44][45] He wrote in a southwestern dialect of Finnish, as Turku was effectively the capital of Finland at the time. However, his texts also displayed features from other dialects, as Agricola himself also acknowledged.[44] Furthermore, Agricola also incorporated various foreign features in Old Literary Finnish, deriving mainly from Swedish, but also from German and Latin. These include compound verbs, articles, and a passive structure like that of the Germanic languages; these are rare or even absent in modern Standard Finnish.[44][32] Approximately 60 percent of the vocabulary used by Agricola remain in use today.[46]

The orthography found in Agricola's works is different in many ways from that of modern Finnish. He modelled Finnish spelling after Swedish, German and Latin.[47] Spellings were much less consistent: the same sound could be spelled in multiple ways depending on the context, and the same letter could denote different sounds.[48] For example, the vowel /æ/ could be spelled as ä or e, and the consonant /k/ could be spelled as k, c or q depending on the following vowel. /ð/ (found in southwestern dialects at the time) was spelled as d or dh, /ɣ/ (unstable and seemingly disappearing) as g, gh, ghi, ghw, and /θθ/ (if not an affricate /ts/ by then) as tz.[48]

After Agricola

[edit]Agricola's writings remained highly influential for almost a century.[44] The first complete translation of the Bible into Finnish was finished in 1642.[49][32] This translation sought to eliminate some of the loanwords used by Agricola and to use fewer foreign sentence structures, showing a puristic tendency.[32][46] Nevertheless, Swedish and German influence was still apparent in at least the syntax.[49] Calques and foreign sentence structures remained common throughout the Old Literary Finnish period, as many texts were translations from Latin or Swedish.[50]

Spelling became more regular in the century following Agricola. Vowels and vowel length began to be marked more consistently, q ceased to be used (but c and k were still used), /ð/ came to be denoted by d, and /ɣ/ by g. These norms set by the 1642 Bible translation were largely followed by subsequent texts.[48] However, the spelling of sounds remained somewhat inconsistent until the late 19th century.[51]

Old Literary Finnish remained based on the southwestern dialects (specifically the variety spoken in Turku[46]). The language in the 1642 Bible translation was even more based on southwestern Finnish than Agricola's texts had been.[52] Features that differ from modern Standard Finnish include the inessive ending -s or -sa (modern standard -ssa),[53] frequent apocope (e.g. punaist for modern punaista, ylistem for modern ylistämme), and the adjectival ending -ia (modern -ea, e.g. hopia for modern hopea).[54] All of these features are still found in dialects today. In the late 17th century, Tavastian and Ostrobothnian dialects began influencing Old Literary Finnish; as the latter had elements of the eastern dialects, these too began to indirectly shape the literary Finnish language for the first time.[32]

Historical events continued shaping the development of Finnish dialects. After Sweden got control of Kexholm County in the 1617 Treaty of Stolbovo, Finnish speakers spread and replaced the Karelian language in most of the region, as most of the Eastern Orthodox Karelians fled to Russia. This included North Karelia, which was settled mainly by Savonians, with the original Karelians remaining only in a few villages. Ingria also saw an influx of Finnish speakers (see § Finnish abroad).[55][38] Finnish also continued spreading north: Kainuu was reached by the 16th century,[56] and Kainuu Sámi went extinct in the 18th century.[57]

Most Old Literary Finnish texts were of a religious nature, but there were also some legal and secular texts.[44][32] Noteworthy works include Henrik Florinus' collection of Finnish proverbs, the first of its kind.[46] In addition, the first dictionary including Finnish words by Ericus Schroderus was published in 1637,[49][58] and the first grammar of Finnish (written in Latin) was published in 1649; an earlier grammar was likely published in 1640 but has been lost.[32][49] The 18th century was a relatively quiet period of development; Finnish-language literature published at this time was predominantly religious.[32] Exceptions include a Finnish translation of the laws of Sweden (finished in 1734 but published only in 1759)[59] and the first scientific work written in Finnish (by Johan Abrahaminpoika Frosterus) in 1791.[46][59] Furthermore, Daniel Juslenius compiled the first comprehensive Finnish dictionary, Suomalaisen Sana-Lugun Coetus, published in 1745.

The 1776 Bible translation, an updated version of the 1642 translation edited by Antti Lizelius, reformed spelling by eliminating c and standardizing on k.[46] Lizelius also started the first Finnish-language serial publication, Suomenkieliset Tieto-Sanomat, although it did not last for long. He also coined many new words, such as tapahtuma "event" and vuosituhat "millennium".[46] At this time, Finnish did not enjoy much prestige; Henrik Gabriel Porthan wrote that earlier in the 18th century, the clergy, gentry and townspeople had regularly used Finnish, but that this was actively changing "without any duress".[52]

Finnish was predominantly written in blackletter, more specifically Fraktur, until the early 20th century. This practice was so common that Finnish text could even be typeset in Fraktur to set it apart from text in other languages (such as Swedish) typed in Antiqua, even within the same sentence.[60] Texts aimed at educated readers transitioned to Roman type (Antiqua) earlier than those intended for the general public. The letter W was also replaced with the "Latin" V during this transition.

Early Modern Finnish

[edit]After Finland was conquered from Sweden by Russia in 1809, views regarding the Finnish language began to change significantly,[61] and the development of the Finnish language accelerated considerably during the Early Modern Finnish period.[32]

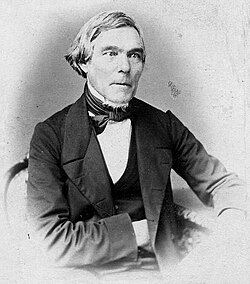

The founding of the Finnish Literature Society in 1831 was one of the key moments during this period. The organization was founded to promote literature written in Finnish and the academic study of the language. Elias Lönnrot, its first secretary,[61] would go on to edit the Finnish national epic Kalevala, which would prove very influential in the development of a Finnish national identity.[62]

Battle of dialects and sound changes

[edit]Old Literary Finnish was based practically entirely on Western Finnish, particularly on the southwestern Finnish dialects. This began to be questioned in the early 19th century in what is now often termed the "battle of dialects" (murteiden taistelu).[63] In 1820, Reinhold von Becker published an article in Turun Wiikko-Sanomat,[32] in which he argued that Eastern Finnish represented a better language than Western Finnish did. Despite this, Becker did not seek to have Western Finnish replaced entirely but to enrich the Finnish language with eastern elements.[61] When he released a Finnish grammar in 1824, he treated the Savonian dialects as the 'reference dialect' and portrayed some Savonian features as those of the standard language itself.[61] Carl Axel Gottlund went even further, liberally using the Savonian dialect in his writings, despite a lack of proficiency in Savonian and in Finnish in general.[61] Some have even claimed that Gottlund sought to replace Old Literary Finnish entirely with a new Finnish based on Savonian dialects, even though he himself wrote that he did not necessarily want to set an example for others to follow.[64]

Ultimately, the western dialects remained the foundation after authors came out in support of Old Literary Finnish. This included Gustaf Renvall, who argued for maintaining Western Finnish as the basis for Standard Finnish.[65] He also sought to weed out foreign (primarily Swedish and German) elements from it while accepting only some Eastern Finnish traits, mostly vocabulary but also some grammatical features.[61] A major influence in the adoption of eastern features was Elias Lönnrot, who had originally believed that standard Finnish should be based on the eastern dialects. He later came to believe that it should instead be a blend of different dialects. As the editor of Kalevala, Lönnrot held considerable sway, and his position prevailed.[61] Consequently, modern Standard Finnish is rather evenly based on both western and eastern features.[66] At the time, Eastern Finnish was also widely understood to include Karelian and Ingrian; a large part of the source material for Kalevala was gathered from regions speaking either of these two. Therefore, they also influenced the development of Standard Finnish during this period.[67]

Among the eastern features adopted into standard Finnish during the Early Modern Finnish period were the inessive ending -ssa/-ssä, accusative forms of personal pronouns ending in -t (e.g. minut) and the non-use of instructive forms of the third infinitive (pitää tekemän > pitää tehdä). Eastern vocabulary was also adopted into Standard Finnish;[68] some words even replaced their Western Finnish counterparts, such as ehtoo > ilta "evening", nisu > vehnä "wheat", and suvi > kesä "summer".[69] In addition, the third-person plural verb ending -vat/-vät replaced the earlier -t,[32] and word-initial consonant clusters—absent in Eastern Finnish even in loanwords—were simplified in many words.[61]

One of the important dialectal differences was the treatment of /ð/, /θθ/ and /ɣ/. Most Finnish dialects had lost these phonemes (/ɣ/ was probably lost everywhere by this point), but the result varied by dialect:

- /ð/ had been spelled as d since the Old Literary Finnish period. In most of the western dialects, it had become either /r/ or /l/, depending on the dialect. In Eastern Finnish (and most Ostrobothnian dialects), the corresponding *-d- was lost entirely[70] (in fact, lost already in Proto-Karelian;[38] but cases like *saada > saaha ~ soaha ~ suaha). Proponents of Eastern Finnish often supported getting rid of d from Standard Finnish entirely, but it ultimately remained;[70] however, some words in Standard Finnish (such as lähettää and viehättää) follow the Eastern Finnish pattern.[71] d came to be pronounced as a voiced plosive /d/ in Standard Finnish. This is often explained as foreign influence, deriving from a spelling pronunciation based on its pronunciation in Swedish.[72]

- /θθ/ (spelled tz in Old Literary Finnish) had usually become /tt/ in Western Finnish, while in Eastern Finnish, *cc had evolved into /ht/, /ss/ or /ts/, depending on the dialect.[73] Eventually, /ts/ became the standard pronunciation; this may be for a similar reason as above for /d/ (i.e., spelling pronunciation by Swedish speakers),[74] but /ts/ was also found in dialects spoken on the Karelian Isthmus.[73]

- /ɣ/ (spelled g in Old Literary Finnish) had been lost (it had already been unstable during Agricola's time[75]), but in Western Finnish, the result was often a glide (kulɣen > kuljen, raɣot > ravot, ulɣos > ulvos), while in Eastern Finnish, the corresponding *-g- was lost entirely (had been lost already in Proto-Karelian;[38] kulɣen > kulen, raɣot > raot, ulɣos > ulos).[76] In this case, Standard Finnish chose to follow a compromise:[61] mostly following Eastern Finnish, but -j- was kept, in line with Western Finnish, after a liquid and before -e- (e.g., kulɣen > kuljen, and by analogy also kulɣin > kuljin). Furthermore, /ɣ/ between two high round vowels became (or had become) /ʋ/ (e.g., suɣun > suvun).[75]

Another noteworthy change in spelling was that plosives after nasals and liquids began to be spelled as voiceless (mb > mp, ld > lt, nd > nt, ng /nk/ > nk, but ng /ŋŋ/ remains). This began in the late 18th century, but became common only in the 19th century.[77] Additionally, the letters x and z fell out of use, the former replaced by ks (first used by author Jaakko Juteini) and the latter (in tz) by ts.[65] Finnish has not had voiced plosives natively (since their early spirantization), although they are found in loanwords (chiefly from the 19th century onwards) and now also in the Standard Finnish pronunciation of d.

Lexicon

[edit]The Finnish lexicon was in dire need of new words in the 19th century.[78] While loanwords were one option, it was considered easier for Finnish speakers to learn new terms derived within the language. New words were formed using derivative suffixes, but many proved irregular until a better understanding of Finnish morphology developed. Besides the use of suffixes, compounds and phrases were also created to express new concepts.[79] Moreover, dialectal words were adopted to the standard language with new meanings (such as juna "line (of things)" > "train", kone "tool" > "machine", and tehdas "place where something is done, worksite" > "factory"). Terms were not created only for new concepts; some were coined to replace existing loanwords in the spirit of linguistic purism.[61]

The single most prolific coiner was Elias Lönnrot, the author of the Kalevala and one of the founders of the Finnish Literature Society. The folk poetry in Kalevala inspired many new words in Standard Finnish. Lönnrot also edited a major Finnish-Swedish dictionary (published in 1880), which introduced a large number of new coinages by Lönnrot and others like Antero Warelius. Lönnrot's coinages (either new words or words adopted with new meanings) include itsenäinen "independent", kansallisuus "nationality", kirjallisuus "literature", kuume "fever", laskimo "vein", monikko "plural", muste "ink", ongelma "problem", tasavalta "republic", and yksikkö "singular".[80][78]

Wolmar Styrbjörn Schildt (Volmari Kilpinen), besides being a prolific translator, was known to coin new words in lists, which he published or sent to Lönnrot. Schildt's coinages that remain in use include aste "degree", esine "thing, object", henkinen "mental", kirje "letter (written correspondence)", myymälä "shop, store", taide "art", and tiede "science".[81][78][82] He also coined henkilö "person", though he later regretted coining a word ending in ö.[78] Perhaps the most ambitious of Schildt's ideas was to change Finnish spelling by using a circumflex (e.g. â) to mark long vowels instead of doubling the letter (aa). This did not catch on despite Schildt's insistence, as Finnish orthography had already become too established.[32][83]

Daniel Europaeus coined many new words, but was never liked by his peers. He came from a partly lowly background, and he was said to be hard to work with. Europaeus also gathered more folk poetry for an expanded edition of Kalevala, including the Kullervo story arc. Some of the words Europeaus coined that are still used are eduskunta "(the Finnish) parliament", enemmistö "majority", huvila "villa", suunnikas "parallelogram", and tasa-arvo "equality".[78][84][85]

Paavo Tikkanen was the editor-in-chief of Suometar, an important newspaper for the development of new Finnish vocabulary.[78] He is credited with coining the words mielipide "opinion", teollisuus "industry"[86] and valtio "state, polity".[78]

Several others also coined multiple words into Standard Finnish, and these include (with some examples for each):

- Reinhold von Becker: ihmiskunta "humanity", keksintö "an invention", sanomalehti "newspaper"; from dialects he adapted sivistää "to civilize"[87]

- Samuel Roos: sähkö "electricity"; from dialects he adapted kaasu "gas", kasvi "plant"[88]

- Abraham Poppius: maantieto "geography"; from dialects he adapted kerätä "to gather", tilaisuus "occasion"[89]

- Carl Axel Gottlund: huutokauppa "auction", kirjasto "library", sepittää "to make up, coin (a word)"[90]

- Pietari Hannikainen: käsityöläinen "artisan, craftsman", neuvosto "council", tulevaisuus "future"[86]

- August Ahlqvist: lähettiläs "emissary", puolue "(political) party"[91]

However, not all proposed coinages were successful, and many (perhaps even the majority) fell out of use. For example, Lönnrot coined the word lieke for electricity, but Roos's sähkö won out in the end.[78]

Status of Finnish

[edit]The growing status of Finnish soon led to a conflict between those favoring Finnish (the "Fennomans") and those favoring Swedish (the "Svecomans").[61] Many of the Fennomans, such as Johan Vilhelm Snellman, were themselves native Swedish speakers who learned to speak Finnish, resulting—for the first time—in a significant population of Finnish-speaking intellectuals.[92]

Academic interest in Finnish grew; many grammars were published in the 1840s and 1850s.[61] Antero Warelius conducted ethnographic studies and surveyed Finnish dialects.[93] Carl Niclas Keckman was appointed as the first lecturer of Finnish in 1829.[94] The first professorship in Finnish language and literature was established at University of Helsinki in 1850;[61] Matthias Castrén was appointed as the first professor, but after he died in 1852,[95] he was replaced by Lönnrot.[61] In 1858, the first Finnish-language school was established in Jyväskylä, largely thanks to Schildt's efforts.[61][78]

A major victory for the Fennomans came in 1863, when Emperor of Russia Alexander II passed the language act that made Finnish an official language in Finland for the first time.[96]

By the end of the Early Modern Finnish period, Finnish was widely used in education, administration, and the justice system.[97] In 1870, Aleksis Kivi published what is widely considered the first Finnish-language novel, Seitsemän veljestä, marking an important development in Finnish literature.

Modern Finnish

[edit]In the Modern Finnish period, new words—both coinages and borrowings—have continued to enter the language. Grammatical and morphological changes have slowed, but not entirely ceased. There has been a preference towards shorter forms (e.g. kutsumus > kutsu, saapi > saa, pojallansa > pojallaan), as well as to further undo Swedish influence on grammar and syntax. Particles like kun and kuin are now distinguished, and the rules for whether to spell certain verbs with -ottaa or -oittaa have been defined.[61][98]

Linguistic purism has continued into the Modern Finnish period. E. A. Saarimaa's language guide, published in 1930, criticized the extensive Swedish influence on Finnish and proved highly influential in the coming decades. Some of the features criticized by Saarimaa have largely disappeared from Finnish, while others remain.[99]

Finland lost approximately 10% of its territory in the Second World War. The South Karelian dialects were affected the most, as most of the dialect region was ceded to the Soviet Union. The dialects were diffused throughout Finland as a result of the resettlement of Finns from the ceded regions to the rest of the country.[100]

The Finnish Language Office (Kielitoimisto) was established in 1945 as part of the Finnish Literature Society. In 1976, it was integrated into the Institute for the Languages of Finland,[101] which remains the authority on Finnish language planning. Nykysuomen sanakirja, the most comprehensive monolingual Finnish dictionary, was published between 1951 and 1961.

Noteworthy 20th-century neologisms that became accepted in Standard Finnish include haastatella "to interview" (Artturi Kannisto, 1907),[102] elokuva "film, movie" (Artturi Kannisto, 1927),[103] mainos "advertisement" (E. A. Saarimaa, 1928),[104] muovi "plastic" (Lauri Hakulinen, 1947),[105] juontaa "to host, present (an event)" (Hannes Teppo, 1951),[106] and palaute "feedback" (1970).[107]

Today, Finnish and Swedish are the two official languages in Finland.[108] Finnish is also one of the official languages of the European Union.[109]

Finnish abroad

[edit]In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Finns mainly from Savonia moved to the forests in western Sweden and eastern Norway and became known as the Forest Finns. The Finnish language survived among them until the 1960s.[110] In the 19th century, Carl Axel Gottlund documented the Forest Finns extensively, advocated for their rights and helped raise attention for their cause in Finland.[64]

In the 17th century, after the Ingrian War, Sweden gained control of Ingria. The Finnic-speaking populations of Ingria, Izhorians and Vots, were of Eastern Orthodox faith. Sweden encouraged Lutheran Finnish settlers to move to the region; they became the Ingrian Finns. By the end of the century, they comprised three-fourths of the population of Ingria.[111] The Ingrian Finnish dialects survived in the region until the Soviet genocide in the 1920s and 1930s.

Finnish speakers also persisted in northern Sweden and Norway. The Finnish speakers in Sweden were separated from the speakers in Finland after 1809, when Russia annexed Finland from Sweden, resulting in a new border. These speakers in the Torne River Valley were thus isolated from 19th-century developments in Finnish, and their language is now referred to as Meänkieli. Whether it is an independent language from Finnish is disputed, although it is recognized as an official minority language in Sweden.[112] Large numbers of Finnish speakers began to move to Norway in the 18th and 19th centuries, and their language is now known as the Kven language; similar to Meänkieli, it is an officially recognized minority language in Norway,[113] and its status as an independent language is disputed.

Finnish migrations resulted in the emergence of a Finnish diaspora in North America. American Finnish does not represent a single, unified variety, as emigrants from different regions brought their dialects with them. While American Finnish has many borrowings from English, they are adapted to fit Finnish phonology and often represent only specialized terms, rather than the core vocabulary.[114] In 2013, Finnish was spoken by 26,000 people in their homes in the United States,[115] and there are also speakers in Canada.

A second Finnish-speaking minority emerged in Sweden mainly due to emigration from the 1950s to the 1970s. In Sweden, Finnish (as separate from Meänkieli) has been an officially recognized minority language since 1999.[116]

References

[edit]- ^ Laakso, Johanna (2001). "The Finnic languages". Circum-Baltic Languages. Studies in Language Companion Series. Vol. 54. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. clxxix–ccxii. doi:10.1075/slcs.54.09laa. ISBN 978-90-272-3057-7.

- ^ Piechnik, Iwona (2014-12-22). "Factors influencing conservatism and purism in languages of Northern Europe (Nordic, Baltic, Finnic)". Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis. 2014 (131, 4): 400. doi:10.4467/20834624SL.14.022.2729. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Aikio, Ante (2022). "Proto-Uralic". In Bakró-Nagy, Marianne; Laakso, Johanna; Skribnik, Elena (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–27. ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4.

- ^ Laakso, Johanna (2022). "Finnic: General introduction". In Bakró-Nagy, Marianne; Laakso, Johanna; Skribnik, Elena (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 240–253. ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4.

- ^ Grünthal et al. 2022, pp. 21, Supplements p. 20: "The Uralic spread took place rapidly (...) The I-I contact episode gives a reliable absolute date for the Uralic divergence and dispersal: not long before 4000 BP." (...) "the western frontier of the Uralic family (...) lay along the upper Volga and Oka."

- ^ Grünthal et al. 2022, Supplements pp. 20–21: "Saamic moved (...) reaching southeastern Finland c. 3000 BP, and some time after that spread to central Scandinavia perhaps as early as 200 CE, (...) Finnic spread separately, starting slightly later. Moving along waterways of what Lang 2018:310 terms the Southwest Passage (middle-upper Oka to the south coast of the Gulf of Finland) (...) it took ancestral Pre-Finnic speakers over half a millennium to reach the Baltic coast."

- ^ Lang 2018, p. 213–214.

- ^ a b Saarikivi, Janne (2022). "The divergence of Proto-Uralic and its offspring: A descendant reconstruction". In Bakró-Nagy, Marianne; Laakso, Johanna; Skribnik, Elena (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–58. ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4.

- ^ Lang 2018, p. 220–222.

- ^ Lang 2018, p. 225.

- ^ Lang 2018, p. 225–226.

- ^ Aikio, Ante (2012). "An Essay on Saami Ethnolinguistic Prehistory" (PDF). Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia/Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (266). Helsinki: 63–117.

- ^ a b Kallio, Petri (2014). "The Diversification of Proto-Finnic". In Ahola, Joonas; Frog (eds.). Fibula, Fabula, Fact: The Viking Age in Finland (Studia Fennica Historica 18). Helsinki, Finland: Finno-Ugric Society. pp. 155–168.

- ^ a b "Itämerensuomi". Suomen vanhimman sanaston etymologinen verkkosanakirja EVE (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Itkonen, Terho (1983). "Välikatsaus suomen kielen juuriin". Virittäjä (in Finnish). 87 (3/1983): 349–386.

- ^ Lehtinen 2007, pp. 156, 166–167.

- ^ Haikala, Topias (2022-10-21). "Ennen suomea ja saamea Suomen alueella puhuttiin lukuisia kadonneita kieliä — kielitieteilijät ovat löytäneet niistä jäänteitä" (in Finnish). University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lehtinen 2007, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holopainen, Sampsa (2019). Indo-Iranian borrowings in Uralic : Critical overview of sound substitutions and distribution criterion. University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-51-5729-4.

- ^ Gertsch, Mia (2018-08-27). "Testaa tunnistatko lainasanan – suomen kielen sanastosta suurin osa on lainattua". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Bentlin, Mikko (2008). Niederdeutsch-finnische Sprachkontakte - Der lexikalische Einfluss des Niederdeutschen auf die finnische Sprache während des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia (in German). Vol. 256. Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5667-02-8.

- ^ Korhonen, Riitta (2008). "Englantia kaikilla kielillä – harmittaako?". Kielikello. 3/2008 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Suomen sanojen alkuperä (in Finnish). Helsinki, FI: SKS. 2000. ISBN 951-717-712-7.

- ^ a b c d e Häkkinen, Kaisa. Chronological stratification of the vocabulary of Finnish (2010)

- ^ a b Häkkinen, Kaisa (2018). "Suomi on kuuden kerroksen kieli". Tiede (in Finnish) (1/2018). Sanoma Media Finland: 36–43.

- ^ a b Kallio 2017, pp. 7.

- ^ Lehtinen 2007, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Savolainen, Erkki (1998). "Suomen murteet" [Finnish dialects]. Internetix (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 30 December 2005.

- ^ Puumala, Anne (2022-11-27). "Tutkimus paljastaa uutta tietoa eteläpohjalaisten kaukaisista juurista – Astelivatko meren takaa tulleet mahtikauppiaat kauan sitten Kyrönjoen rantoja?". Ilkka-Pohjalainen (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-21.

- ^ Paunonen, Heikki. Suomen murteiden ryhmittelystä ja niiden suhteesta viron murteisiin (2023). p. 221

- ^ Häkkinen 2016, pp. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lång, Markus (1996). "Suomen ja viron kirjakielestä: katsaus historiaan ja kielenohjailuperiaatteisiin". Markus Långin kotisivu (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 2012-02-04.

- ^ a b Heikkilä, Mikko (2016). "Varhaissuomen äännehistorian kronologiasta". Sananjalka (in Finnish). 58: 136–158.

- ^ Kallio 2017, pp. 9.

- ^ Kallio 2017, pp. 12.

- ^ Kallio 2017, pp. 14.

- ^ Kallio 2017, pp. 19.

- ^ a b c d Kallio, Petri (2018). "Muinaiskarjalaista dialektologiaa" (PDF) (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Kallio 2017, pp. 11.

- ^ Wulf, Christine (1982). "Zwei Finnische Sätze aus dem 15. Jahrhundert". Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher (in German). 2: 90–98.

- ^ Häkkinen 2016, pp. 17.

- ^ Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhaan kirjallisuuteen. 1. Prologi. Ennen kirjasuomea". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Häkkinen 2016, pp. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhaan kirjallisuuteen. 2. Vanha kirjasuomi 1540-1640". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b Heininen, Simo. "Agricola, Mikael (1510 - 1557)". National Biography of Finland. The Finnish Literature Society. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Palkki, Riitta (2000). "Abckiriasta almanakkaan: kirjoitetun suomen alkuvuosisadat". Kielikello. 1/2000 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 74–76.

- ^ a b c Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhan kirjasuomen ortografiaan". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b c d Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhaan kirjallisuuteen. 3. Vanha kirjasuomi 1640-1700". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 3.

- ^ "Vanha kirjasuomi kielimuotona: Vanhan kirjasuomen oikeinkirjoituksen piirteitä". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-21.

- ^ a b Kolehmainen, Taru (2009). "Pipliasuomesta yleissuomeen". Kielikello. 2/2009 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-21.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 128.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 112, 117, 160.

- ^ Torikka, Marja (2003). "Karjala". Kielikello. 1/2003 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Keränen, Jorma (1984). Kainuun asuttaminen (in Finnish). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto.

- ^ Irja Seurujärvi-Kar (2011). ""We Took Our Language Back" – The Formation of a Sámi Identity within the Sámi Movement and the Role of the Sámi Language from the 1960s until 2008" (PDF). p. 39. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

...Kainuu Sámi (used until 16th–18th century in the area of the Forest Sámi people in central Finland and in the Republic of Karelia).

- ^ "Kansalliskielet: Suomen kieli". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhaan kirjallisuuteen. 4. Vanha kirjasuomi 1700-luku". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Mäkipere, Tuovi (2023-01-07). "Tiesitkö: Koukeroinen fraktuura eli suomenkielisten tekstien kirjaintyyppinä pitkään – nykyään sitä näkee lähinnä kaupan karkkihyllyssä". Maaseudun Tulevaisuus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Forsman Svensson, Pirkko. "Katsaus vanhaan kirjallisuuteen. 5. 1800-luvun kirjasuomi". Virtuaalinen vanha kirjasuomi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Vento, Urpo. "The Role of The Kalevala" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 292.

- ^ a b Laitinen, Lea (2018-01-25). "Kymmenen kohtaa aiheesta Carl Axel Gottlund ja kieli". Juvan kulttuurisivut (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b Lauerma, Petri (2022). "Kolme aaltoa, rokotus ja karanteeni". Kielikello. 3/2022 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 6.

- ^ Kallio, Petri. Muinaiskarjalan uralilainen tausta (2018)

- ^ Vilppula, Matti (1984). "Kirjakieli ei "ala rappeutumaan"". Kielikello. 2/1984 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Häkkinen 2016, pp. 125.

- ^ a b Pulkkinen, Paavo (1994). "Mahotonta ahistusta". Kielikello. 2/1994 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Punttila, Matti (2001-11-13). "Mistä kirjakieleemme tuli d?". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Nordlund, Taru (13 January 2012). "Standardization of Finnish orthography: From reformists to national awakeners". In Baddeley, Susan; Voeste, Anja (eds.). Orthographies in Early Modern Europe. De Gruyter. pp. 351–372. doi:10.1515/9783110288179.351. ISBN 978-3-11-028817-9.

- ^ a b Kettunen, Lauri (1940). Suomen murteet III A. Murrekartasto [Dialects of Finnish III A. Dialect atlas.] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023.

- ^ E. N. Setälä (1890). Yhteissuomalaisten klusiilien historia: luku yhteissuomalaisesta äännehistoriasta (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. p. 177.

- ^ a b Häkkinen 2016, pp. 83.

- ^ Punttila, Matti (2001-12-18). "Murteellisuuksia kirjakielessä". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lauerma, Petri. "Kirjakieli 1800-luvulla: Kirjakielen ortografian kehitys". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ali-Hokka, Heikki (2024-02-28). "Lönnrot ja muut kielinerot tehtailivat sanoja: "tiede" ja "taide" jäivät käyttöön, "pölkäre" ei kelvannut kuutioksi". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ "Kirjakieli 1800-luvulla: Kirjakielen sanaston kehitys". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 295–299.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Lönnroth, Harry; Laukkanen, Liisa (2023). "Wolmar Schildt suomentajana". Sananjalka (in Finnish). 65: 281–290.

- ^ Audejev-Ojanen, Pirkko (2006-12-21). "Venytysmerkkilöt – Wolmar Schildtin omat kirjaimet". Verkkomakasiini – Jyväskylän yliopiston kirjaston tiedotuslehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Pihlaja, Riitta (2014-03-21). "Hankala savitaipalelainen toi suomen kieleen tasa-arvon, huvilan ja eduskunnan". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Kivimäki, Petri (2020-11-30). "Tämä kummallinen mies keksi kymmeniä sanoja, joita sinäkin käytät päivittäin – ilman häntä Tolkienin maailmankuulu fantasiaklassikko olisi voinut jäädä syntymättä". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ a b Hakulinen 1961, pp. 300.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 294.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 295.

- ^ Hakulinen 1961, pp. 300–301.

- ^ "Käsikirjasto: Fennomania". SKS: Kieli ja identiteetti (in Finnish). Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ "Warelius, Anders". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). 1921. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ Matti, Klinge. "Keckman, Carl Niclas (1793 - 1838)". Kansallisbiografia (in Finnish). Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Salminen, Tapani. "Castrén, Matthias Alexander (1813 - 1852)". Kansallisbiografia (in Finnish). Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Trötschkes, Rita (2013-06-11). "Keisarivierailu vauhditti yhteiskunnan muutosta". Yle (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 9.

- ^ Lehikoinen & Kiuru 1991, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Kolehmainen, Taru (2009). "Kielenhuoltoa svetisismien varjossa". Kielikello. 3/2009 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Leskinen, Heikki (1974). "Karjalaisen siirtoväen murteen sulautumisesta ja sen tutkimisesta". Virittäjä (in Finnish). 78 (4/1974): 361–378.

- ^ "Kielitoimiston historia". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Aapala, Kirsti. "Sanojen alkuperä: Haastatella". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Aapala, Kirsti. "Sanojen alkuperä: Elokuva". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Aapala, Kirsti. "Sanojen alkuperä: Mainos". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Aapala, Kirsti. "Sanojen alkuperä: Muovi". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Häkkinen, Kaisa (2004). Nykysuomen etymologinen sanakirja (in Finnish). Helsinki: WSOY.

- ^ Eronen, Riitta (2015). "Sanakilpailuja ja kilpailusanoja". Kielikello. 1/2015 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ "Suomen ja ruotsin kieli". Oikeusministeriö (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ "Languages". European Union. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Auramo Paaer, Sanna (2022-09-30). "Keitä ovat metsäsuomalaiset ja mistä he tulivat?". SVT.se (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ "Ruotsin kuningaskunnan Inkeri". Tietävä (in Finnish). Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Mantila, Harri (2000). "Meänkieli, yksi Ruotsin vähemmistökielistä". Kielikello. 3/2000 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Saloranta, Antti; Heikkola, Leena Maria (2025-05-07). "Mitä kveenille kuuluu? Vähemmistökielen elvytys Norjassa". Kielikello (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- ^ Virtaranta, Pertti (1992). Amerikansuomen sanakirja = A Dictionary of American Finnish (in Finnish). Siirtolaisuusinstituutti. ISBN 951-9266-43-7.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English". United States Census Bureau. October 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Ehrnebo, Paula (2000). "Suomesta virallinen vähemmistökieli Ruotsissa". Kielikello. 3/2000 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten keskus. Retrieved 2025-09-20.

Bibliography

[edit]- Grünthal, Riho; Heyd, Volker; Holopainen, Sampsa; Janhunen, Juha A.; Khanina, Olesya; Miestamo, Matti; Nichols, Johanna; Saarikivi, Janne; Sinnemäki, Kaius (2022-08-29). "Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread". Diachronica. 39 (4): 490–524. doi:10.1075/dia.20038.gru. ISSN 0176-4225.

- Hakulinen, Lauri (1961). The Structure and Development of the Finnish Language. Indiana University Publications Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 3. Translated by Atkinson, John. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Häkkinen, Kaisa (2016). Spreading the Written Word: Mikael Agricola and the Birth of Literary Finnish. Translated by Pearl, Leonard. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 978-952-222-755-3.

- Kallio, Petri (2017). "Äännehistoriaa suomen kielen erilliskehityksen alkutaipaleilta". Sananjalka (in Finnish). 59: 7–24.

- Lang, Valter (2018). Läänemeresoome tulemised. Muinasaja teadus 28 (in Estonian). Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus. ISBN 978-9949-77-662-7.

- Lehikoinen, Laila; Kiuru, Silva (1991). Kirjasuomen kehitys (in Finnish). Helsinki: Helsingin yliopiston suomen kielen laitos. ISBN 951-45-5073-0.

- Lehtinen, Tapani (2007). Kielen vuosituhannet (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-951-746-896-1.

Further reading

[edit]- "Kirjakieli 1800-luvulla". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-09-20.

- Lauerma, Petri (2018). "The development of 19th century Finnish vocabulary in the light of Martti Rapola's word collection". Folia Uralica Debreceniensia. 25. Debrecen: Debrecen University Press.