Hachikō

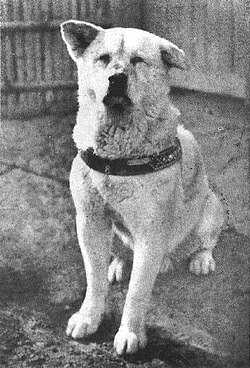

Hachikō (c. 1934) | |

| Species | Dog (Canis familiaris) |

|---|---|

| Breed | Akita |

| Sex | Male |

| Born | mid-November 1923[1][2] near Ōdate, Akita, Japan |

| Died | March 8, 1935 (aged 11) Shibuya, Tokyo |

| Resting place | Aoyama Cemetery |

| Known for | Faithfully waiting for the return of his deceased owner for more than nine years until Hachikō's death. |

| Title | Chūken Hachikō (忠犬ハチ公, 'faithful dog Hachikō' or 'loyal dog Hachikō') |

| Owner | Hidesaburō Ueno |

| Weight | 41 kg (90 lb) |

| Height | 64 cm (25 in)[3] |

| Appearance | White (peach white) |

| Awards |

|

Hachikō (ハチ公; mid-November 1923 – March 8, 1935)[1][2] was an Akita dog remembered for his strong dedication to his owner, Hidesaburō Ueno, for whom he continued to wait for almost 10 years following Ueno's death in 1925.

Hachikō was born in mid-November 1923, on a farm near Ōdate, Akita Prefecture, Japan.[4] In 1924, Hidesaburō Ueno, a professor at the Tokyo Imperial University, brought him to live in Shibuya, Tokyo as his pet. Hachikō would meet Ueno at Shibuya Station every day after his commute home. This continued until May 21, 1925, when Ueno died of a cerebral aneurysm infarction while at work. From then until his death on March 8, 1935, Hachikō would return to Shibuya Station almost every day to await Ueno's return.

After Ueno's death, Hachikō was treated very poorly by most people who worked at or came to Shibuya Station. This did not deter him. After he became nationally known, his story of fidelity and loyalty grew and he came to be treated better. He also had significant health problems his entire life. After he became known internationally, his story led to Helen Keller bringing the first Akita to America. Since his death, he continues to be remembered worldwide in popular culture with statues, movies and books.

Life

[edit]Birth and naming

[edit]There has been much confusion and misinformation about the birth and naming of Hachikō. Hachikō, a creamy-white Akita, was born in mid-November 1923,[1][2] at a farm located in Ōdate, Akita Prefecture, Japan. He was one of four purebred Akita puppies, all male, through his father Ōshinai-yama-gō ("Ōshinai mountain") and mother Goma-gō ("Sesame").[5] The suffix "gō" has no particular meaning but is used for purebred animals, art, airplanes, and trains.[6] Claims that Hachikō was not a purebred Akita have been discredited.[7] Much of the confusion surrounding his birth stems from a fake birth certificate issued in 1934. This fake certificate lists his date of birth as November 20, as well as wrong parents.[8] However, his birthdate is often celebrated as November 10.[9][10] Akita puppies were given to their new owners prior to them turning two months old. Since we know Hachikō was shipped from Ōdate on January 14, 1924, it is likely he was born after November 14, 1923.[11] Hachikō's true provenance was not proven until May 1975.[12]

Various theories have been espoused for the origin of Hachikō's name. Some sources say the name Hachi (八, “eight”) was chosen because Professor Hidesaburō Ueno noticed Hachikō's forepaws resembled the shape of the kanji for eight when he stood up.[13] Others say it was because Hachikō was the eighth puppy in a litter of eight puppies.[10] According to Professor Mayumi Itoh, the real reason the puppy was named Hachi has not been conclusively proven. Additional theories Itoh mentions are that at the time it was a popular name for dogs and that the name means good fortune.[14] Itoh offers this explanation as being more plausible:[14]

The decisive clue came from the four Akita puppies that Ueno had raised previously. They were named Tarō, Tarō II (or Jirō, depending on the source), Gorō, and Roku (or Rokurō). Tarō was the most common name for the first-born boy in Japan at that time. In turn, Jirō refers to the second-born boy. Gorō means the fifth-born boy. Roku means six, and Rokurō the sixth-born boy. Ueno most likely named the last Akita-inu Roku, because Rokurō sounds somewhat tongue tied. Following this sequence in numbers, Ueno should have named the next Akita puppy Shichi (seven) or Shichirō (the seventh-born boy). However, people native to Tokyo spoke the traditional Tokyo dialect, as some Londoners in England spoke with a Cockney accent. Many Tokyoites could not pronounce the word “shichi” articulately, and pronounced it “hichi,” instead. Therefore, Ueno skipped seven, and named the puppy Hachi (eight). He omitted “rō” from Hachirō (as he had done for Rokurō), because Hachirō also sounds somewhat tongue tied. Hence, the naming of Hachi came about. This would make sense. This interpretation of the naming of Hachi has never been presented in any of the literature on Hachi.

— Mayumi Itoh (2017, Hachikō: Solving Twenty Mysteries about the Most Famous Dog in Japan, pages: 51-53)

Hachikō is also known in Japanese as chūken Hachikō (忠犬ハチ公, 'faithful dog Hachikō' or 'loyal dog Hachikō'), with the suffix -kō (公) in the meaning of noble person, prince, duke, lord;[15] in this context, it was an affectionate addition to his name Hachi. The kō suffix seems to have become common after a 1932 article on Hachikō appeared in The Asahi Shimbun.[16]

Life with Ueno

[edit]![Young man with three dogs[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/Hachiko_puppy.webp/208px-Hachiko_puppy.webp.png)

Ueno was an agriculture professor at the Tokyo Imperial University and the pioneer of agricultural engineering in Japan.[18] Contrary to what is often reported, Ueno did not pay ¥30 for Hachikō. He was a gift from Chiyomatsu Mase, a former student of his.[a] Mase was head of the Arable Land Cultivation Section in Akita Prefecture. Mase arranged for Reizō Kurita, one of his employees, to find an Akita puppy for Ueno. Kurita moved to Akita Prefecture into the house right beside Hachikō's owners, Saitō Giichi and his wife Mura. Kurita became well acquainted with Mura and asked for a puppy for Ueno.[20] Kurita and two companions walked the 12.5 miles from the Saitō farm to the train station in a blizard.[21] Hachikō was sent in a straw bag with cookies,[b] which he did not eat, on a train journey to live with Ueno in Shibuya, Tokyo.[18][20][23] The puppy left Ōdate on January 14, 1924 and arrived in Tokyo on January 15, 1924,[c] at Ueno Station, not Shibuya Station as is often reported due a fake postcard the Shibuya stationmaster made. The arrival at Ueno Station was not firmly proven until November 1979.[25] These details of how Hachikō came to be Ueno's pet were not known until May 1975 when Yūkichi Muraoka, executive director of the Society for the Preservation of Akita-inu, found two letters from Kurita to Saiji Giichi, Saitō Giichi's son.[12] Saitō Giichi and Mura are also the maternal grandparents of Yasushi Akashi, a former United Nations Under-Secretary-General, the only Japanese person to hold such a position.[18][26]

Upon arrival in Tokyo, Hachikō was at first thought to be dead, due to an exhaustive bumpy train ride through mountains in the winter,[27] but Ueno and his common law wife, Yaeko Sakano, were able to bring him back to health after six months.[23][28] The exhausting train journey may have been the cause of Hachikō's chronic illnesses.[29] Ueno doted on the dog, allowing Hachi to sleep indoors and under his western-style bed, raising him with affectionate care.[30][31] Hachikō had digestive problems, causing diarrhea, for his whole life, so Ueno and Yaeko followed a strict dietary regimen for him.[32] Ueno would commute daily to work, and Hachikō would leave the house to greet him at the end of the day at Shibuya Station.[33] Locals and station staff soon became familiar with the pair and observed the dog’s daily routine. The pair continued the daily routine until May 21, 1925, when Ueno did not return.[34] Ueno died of a cerebral aneurysm infarction while in the office of a colleague, Hiroaki Yoshikawa, not while giving a lecture nor in a faculty meeting, though he had been at a faculty meeting that morning.[35]

Multiple moves

[edit]

That evening, Hachikō went to Shibuya Station as usual, but Ueno never returned. Hachikō, not understanding that his owner had died, showed up as usual in the evening and waited for Ueno’s arrival.[10][36] When Ueno failed to come home, Hachikō acted distressed and sniffed and paced around Ueno’s empty house.[13] On May 21, the day Ueno died, Yaeko wrapped Ueno's blood-stained shirt inside a futon and placed it in outdoor storage. The next day, May 22, Hachikō went missing. A servant found him in the outdoor storage three days later, on May 24. Hachikō had not eaten anything.[36] Ueno's wake was held at his home on May 25 and Hachikō stayed under Ueno's coffin.[37] The next day, May 26, Hachikō went back to Shibuya Station to wait for Ueno.[38] Despite having been with Ueno only about 15 months, Hachikō waited for Ueno, "commuting" almost daily for the next nine and half years,[d] and eventually attracted the attention of others. Many people who visited the Shibuya train station saw Hachikō daily. In the weeks that followed, Yaeko and colleagues made arrangements for the dog’s care. Hachikō was given to new caretakers numerous times, and sent to the countryside briefly, but repeatedly escaped or wandered back to the Shibuya area.[13] There is little verified information about Hachikō for the timeframe 1925-1928 and much of that is contradicting.[41]

Ueno's students were so loyal to him that they had built a vacation home for him and Yaeko.[42] He had also adopted a daughter, Tsuruko. Tsuruko had married Yasushi Sakano and they had at least one child, a girl named Hisako, born in February 1924,[43] nickname Chako-chan. Ueno's passing was financially devastating for Yaeko and Tsuruko. Ueno's students sold the vacation house since Yaeko could not inherit it since they were never legally married, and used the proceeds to build a house in Tsurumaki in Setagaya ward in Shibuya and support the surviving family. These events took about two years and resulting upheaval was also hard on Hachikō, which is why there is so little verified information on him during this time.[44]

Ueno and Yaeko had two other dogs, an English Pointer named John, and a black mix named Esu.[17] Yaeko had to move out of their home in early July 1925, two months after Ueno's death. She could only take one dog to this rental home, Esu; apparently because she could not ask relatives to take care of him because he was aggressive. John and Hachikō went to a relative, Watanabe, who ran a kimono shop in Tokyo, where they were kept tied up all day, except for one walk a day. This stay only lasted a couple weeks and Hachikō went to Sada, Yaeko's elder sister, and her husband, Nenokichi Takahashi, in mid-July. Hachikō never saw John again.[45] Takahashi ran a business making barbershop chairs. They had a dog simply named "S", who got along well with Hachikō. This family lived in the Asakusa ward of Tokyo. While the Takahashi's took good medical and dietary care of Hachikō, they kept him tied up in the backyard all day to a barber chair and his diarrhea problems continued. According to “The Tale of Loyal Dog Hachi-kō” (1934), by Kazutoshi Kishi, one day Hachikō broke free of his nailed-down leash and got involved in a fight with others. Several spectators hit Hachikō with tools and wanted to kill him, but Kōichirō, son of the Takahashi's, stopped them. According to Kishi, Hachikō stayed with the Takahashi's until the summer or early fall of 1927. Hachikō then went to live with Yaeko in the house Ueno's student built for her in Setagaya. Here he was allowed to roam free again, but he trampled farm fields and did not get along well with Esu.[46] Much of Kishi's story is considered fiction and non-credible.[47]

In “Anthology of Hachi-kō Literature” (1991), Masaharu Hayashi relates the story of Tomokichi Kobayashi, the younger brother of Ueno's gardener, Kikusaburō Kobayashi, known as "Kiku-san”. Tomokichi lived in Kikusaburō's house during this time. Tomokichi states Hachikō only lived in Asakusa one month, but confirms he was tied to barber chair in the Takahashi's backyard. As it was clear Hachikō was unhappy, Yaeko asked Kikusaburō to take care of him. When Tomokichi went to pick up Hachikō from the Takahashi's in Asakusa, Hachikō was elated and according to Tomokichi, Hachikō knew he was going home to Shibuya. By this time Hachikō was so large no one could force him to move. Halfway back to Shibuya, Hachikō was exhausted and famished so he sat down and would not move. Tomokichi found a restaurant and fed Hachikō, so they continued the journey to Shibuya. There is also a report by a local historian, Kichiji Watanabe, of Hachikō being back in Shibuya near the Kobayashi residence April 1926, well before Yaeko's new home in Setagaya was completed.[48] The Kobayashi home was near the Shibuya Station. Tomokichi also denies a story that Hachikō broke free from the home in Asakusa and ran back to Ueno's former residence.[47] In addition to being Ueno's gardener, Kikusaburō was also his handyman and did chores and errands for him. Ueno was away convalescing when Hachikō arrived in Tokyo. He had asked his adopted daughter, Tsuruko, to pick up Hachikō, but Kikusaburō is the person who picked Hachikō up at Ueno Station on January 15, 1924.[49] He knew Hachikō from his gardening work, had played with him, and his home was a mere 20-minute walk from Shibuya Station, an area Hachikō knew well. In the summer of 1925, Yaeko made the hard decision to gift Hachikō to Kikusaburō as she knew he would be happy there.[50] It is possible, but unproven, that Hachikō lived with Yaeko one or more times during these moves. Tomokichi's is considered credible.[47]

Neverending search

[edit]

Despite the disruptions of moving around and not always being well treated, as soon as Hachikō moved in with the Kobayashis, he resumed traveling to Shibuya Station almost daily. Each day regardless of the weather conditions, he appeared in front of the station’s ticket gates, appearing precisely at the same spot and time when the train was due to arrive.[23][51][52] Kikusaburō had a son, Sadao, who was born January 5, 1924, ten days before Hachikō arrived in Tokyo, so they grew up together. In 1990 Hayashi also interviewed Sadao for his book “Anthology of Hachi-kō Literature”. Sadao reported that his father was devoted to Hachikō as a living memento of Ueno and treated him better than he treated his own children. Sadao also relates that Hachikō was so big that people were often afraid of him and that Hachikō was very afraid of the sound of guns, thunder, and lightning. Guns could be heard at their home from the nearby Yoyogi Military Exercise Field, which would send Hachikō hiding in the children's room closet, which he also did when he heard lightning.[53] If the sound of guns or lightning occurred when Hachikō was not at home, he would run into anyone's home to hide.[54] But Hachikō loved snow. He would slide downhill in snow, using his head and neck to steer.[55] Tomokichi remembered Hachikō fondly and loved spending time with him. He also says Ueno fed Hachikō raw meat, which may have caused Hachikō's dirofilariasis (heartworm). Tomokichi also denies the claims Ueno took Hachikō to classes, as Ueno knew some people were afraid of dogs.[56]

In the Spring of 1929 Hachikō developed a case of the mange so bad he lost all his hair and almost died. The Kobayashi family refused to give up on him and Hachikō eventually recovered. Prior to this Hachikō's left ear drooped slightly as a result of a dogfight. After this, his left ear drooped even more than it had before.[57] By 1933, Hachikō was getting old and the Kobayashis built a wooden bed with straw for him to stay in at Shibuya Station to help protect him from the winter cold. He kept "commuting" to the station until he started having trouble walking, which was about three months before he died. Afterwards, he would sometimes stay at Shibuya Station overnight. While they took excellent care of Hachikō, the Kobayashis felt he was usually sad, not acting quite the same as when Ueno was alive.[58] In addition to being known for stopping dogfights, Hachikō was known to be calm, gentle, composed, and dignified.[59]

While the Kobayashi brothers adored Hachikō, they were busy with their work, so they let him roam free. He would go to Shibuya Station every morning around 9am and return between 5-6pm. Thus began Hachikō's solo routine.[60]

Some vendors near Shibuya Station are known to have fed Hachikō and been kind to him.[61] However, initially most people were not so friendly. Hachikō, seen as a stray and nuisance because he was always alone,[51] was mistreated by most station workers, vendors, passengers, and children by acts such as being kicked, hit, pushed, having marks put on his face, and yakitori vendors pouring water on his face.[23][52][62] Because he was usually considered a stray and his collars were often stolen, Hachikō was caught by dog catchers several times. Fortunately one of the policemen knew him and would return him to the Kobayashi family.[63] In 1931-1932 a policeman was chasing a thief through the station but the policeman lost the thief in the crowd. Hachikō found the thief in the crowd and the policeman arrested him. Afterwards some people at the station started treating Hachikō better,[64] but the abuse did not fully stop. In January 1934 a group of 4th grade girls from the nearby Uguisudani Elementary School wrote a letter to Stationmaster Tadaichi Yoshikawa in which they donated money for Hachikō's statue and reported that they had recently seen a slightly older boy kick and step on Hachikō and a station employee pour water on him in the winter.[65] Despite this abuse, Hachikō kept coming almost every day. He normally walked with his head down and looked as if was in mourning.[66]

Hirokichi Saitō was a descendant of samurai and trained in fine art. He founded the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Dogs in May 1928 and studied Akitas and other breeds native to Japan. In July 1928 he saw Hachikō in front of a tea shop and tried to catch him, offering rice crackers, but Hachikō kept running off. Eventually Hachikō ran into Kikuzaburō's house and Saitō learned about Hachikō's life. This is when Saitō realized he had seen Hachikō twice before when he was horseback riding while a student, in 1924 and 1925.[67][68] A month later, in August 1928, Saitō published his first issue of the Registry of Japanese Dogs, which includes the first written record of Hachikō:[69]

Hachi must have missed the late Dr. Ueno Hidesaburō very much. Soon after Hachi was taken to the house of Dr. Ueno’s widow’s kin in Asakusa, Hachi was found at the former residence of Dr. Ueno . . . After Hachi had moved into Mr. Kobayashi Kikusaburō’s house, Hachi stopped going to the former Ueno residence, probably because he realized that the Ueno family was gone and a different family lived there. Therefore, Hachi seemed to miss Shibuya Station the most. Whenever Mr. Kobayashi unleashed Hachi, he went straight to Shibuya Station.

— Mayumi Itoh (2017, Hachikō: Solving Twenty Mysteries about the Most Famous Dog in Japan, page: 100)

Saitō also wrote:[70]

When Hachi moved into the Kobayashi residence, a newspaper deliveryman who lived in the neighborhood cared for Hachi, and gave him good amount of exercise. But he died soon afterward in a traffic accident. After that, Kobayashi alone could not give Hachi enough exercise, and ended up letting him go free. Then, Hachi went straight to Shibuya Station and this became a routine. Hachi left the Kobayashi residence in the morning and came back in the evening. He kept this routine every day . . . There was also a person in the neighborhood of Shibuya Station, who was kind to Hachi before he became famous. This person, about age 30, worked at a stationery store across the street from the police station, which was under the railroad tracks. I saw him often giving Hachi water. I met him and asked him to take care of Hachi, but this person died soon. Strangely, two of the few people who were kind to Hachi before he became famous died young . . . Hachi was too gentle a dog for his own good. He did not bark at other dogs or people. He only occasionally made a soft, low-pitched “woof” sound. I bought yakitori from the vendor for Hachi, and he played “paw,” “sit,” and “turn around” with me. When Mr. Kobayashi put an expensive collar and harness on him, people stole them right away. People also stole his ID tag, because it was considered a good-luck charm for safe childbirth. Despite the fact that Mr. Kobayashi had registered Hachi at the Yoyogi police station, dogcatchers mistook Hachi as a stray dog and caught him. This was so because people had stolen his ID tag and his collar and harness. When Hachi wandered into the small parcels room of Shibuya Station, employees smacked him and even painted graffiti on his face with Japanese ink. I once saw Hachi coming out of the station employees’ room, with dark circles around his eyes, looking like he was wearing black-framed eyeglasses. His snout had curved lines, looking like he was wearing a black mustache. I also saw the yakitori vendor chasing Hachi away in the evening. I felt sorry for Hachi. He looked sad as if he were in mourning.

— Mayumi Itoh (2017, Hachikō: Solving Twenty Mysteries about the Most Famous Dog in Japan, pages: 100-102)

Saitō's research found only 30 purebred Akitas in all of Japan, including Hachikō.[71] He returned to visit Hachikō several times and over the years he published many articles about Hachikō's steadfast loyalty. Saitō wrote a biography of Hachikō in September 1932, in Nihon-inu (Japanese Dogs), the newsletter of the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Dogs, reporting his description as: "going on 9, as: Name: Hachi-gō; Coat color: light yellow; Height: 64.5 centimeters (about 2 feet and 2 inches) from the ground to the shoulder; Weight: about 11 kan (41.3 kilograms or 91 pounds); and Tail: curled-up counter clockwise."[3]

National fame

[edit]

The first appearance of an article about Hachikō in Asahi Shimbun, on October 4, 1932, made him famous nationwide by highlighting his loyalty and mistreatment. Saitō had submitted the article but was not informed it was going to be printed. Its title was Itoshiya rōken monogatari: Ima wa yoninaki shujin no kaeri o machi-kaneru shichi-nenkan (Tale of a Poor Old Dog: Patiently Waiting for Seven Years for the Dead Owner). The journalist who wrote the article did not consult with Saitō and it is full of factual erorrs. Saitō got the newspaper to print a correction under the title Hachi-kō wa meiken (Hachi-kō is a Fine [Pedigree] Dog) that ran on November 5, 1932. The original was written by a journalist who worked for a national news agency and it ran all over Japan and unexpectedly made Hachikō famous.[72] People started to bring Hachikō food while he waited.[23][52][73] Teachers and parents used Hachikō as an example for children to follow. Teru Andō built a sculpture of the dog. All over Japan a keener awareness of the Akita breed grew. Hachikō's faithfulness also became a national symbol of loyalty.[74]

On November 6, 1932 Hachikō was one of only two dogs invited as guests to the first Japanese Dog Show in Ginza-Matsuya, a large Tokyo department store. Hachikō refused to get in the taxi for Kikusaburō to ride to the show until Yaeko came. Hachikō was very composed and popular at the show. Many people came just to see him.[75][76] Shinpa theater actor Masao Inoue became a fan of Hachikō and fed him.[77]

In June 1933 sculptor Teru Andō visited Saitō to confer about making a plaster statue of Hachikō. Andō was on the sculpture jury of the Imperial Fine Arts Academy. Andō and Saitō had known each other at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (currently Tokyo University of the Arts). Andō felt Hachikō had a special aura and was mesmerized by him. Andō decided to make the statue accurate, with the left ear drooping, rather than as an idealized Akita, which caused some backlash. The statue was well-received at the exhibition.[78]

As Hachikō's fame grew, so did the number of people coming to see him at the station. Consequently, on September 9, 1933, Stationmaster Yoshikawa hired a man named Satō (surname, given name not known) to take care of Hachikō. Saitō had checked Hachikō's ID tag but no one at the station bothered to until November 17, 1933, when Stationmaster Yoshikawa had Satō to do so. Satō found the ID tag No. Yo-125 on his collar. "Yo" indicates the Yoyogi police station. Despite not having shown interest in Hachikō before, such as not checking his ID tag, Yoshikawa started faking documents to capitalize on his fame.[79] Satō kept a 6-volume journal about Hachikō titled Chūken Hachi-kō kiroku (Record of Loyal Dog Hachi-kō), consisting of two three-volume sets. The first covers the time up to his death and is titled Shōten (Ascent to Heaven). The second set, titled Dōzō (Bronze Statue) covers the making of his statue. The Shibuya Station building burned during a World War II air raid on May 25, 1945. Satō's journal survived the many wartime Tokyo air raids and is kept at the Society for the Maintenance of the Hachi-kō Bronze Statue, in the Japan Railways Group (JR) East Japan Shibuya stationmaster’s office. Hachikō attended two more Japanese Dog Shows on November 3, 1933 and in September 1934. Both shows went well for him but by this time he was old and very tired.[80] On November 21, 1933 Hachikō was made a member of the Pochi Club, an international dog welfare organization and given their badge.[81] Hachikō appeared on the Japanese Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications New Year's postcard for 1934, Year of the Dog. The card was designed by Seiho Ōuchi.[82]

Death

[edit]

By November 1933, having turned age 10, Hachikō's age and medical conditions were taking a serious toll on him. By this time he had dirofilariasis (parasitic infection), which is caused by dirofilaria immitis (heartworm), and ascites (fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity), a complication of dirofilariasis. Saitō was concerned that Hachi might not make it through this winter.[83] Hachikō became very ill on February 6, 1934 but recovered on February 17. On February 18, the film star Yoshiko Kawada visited him at Shibuya Station. A photo was taken of just her in a kimono and Hachikō in which she is often mistaken for Yaeko, but there is no known photo of Yaeko and just Hachikō. At this time Stationmaster Yoshikawa played another trick on Hachikō by tying a red shipping tag that said "Handle with care" on him.[84] The Shibuya stationmaster also tried to have his name engraved on the base of the statue's pedestal.[85] In early March 1935, Hachikō became extremely ill. He began vomiting, stopped eating, and his abdomen was very swollen with the ascites.[86]

Hachikō died on March 8, 1935, at the age of 11, having been found around 6am, his body still warm. He was found at an alley entrance just north of the Takizawa Liquor Store at 41, 3-chōme, Nakadōri, Shibuya ward. This is near the Inari Bridge in Shibuya.[4] He was found at the alley entrance by Haruno Takizawa, wife of Seiji Takizawa, the owner of the liquor store. Haruno found Hachikō's body at the wooden gate to their house, which is at the alley entrance. She stroked him and called his name. Hachikō was found with his head towards the east, in the direction of Aoyama Cemetery, where Ueno rests.[86] Around 11pm the night before he died, Hachikō visited every store in front of Shibuya Station. Around midnight he visited every room at the station. Haruno's son, Ryōichi, eventually took over the liquor store. He states Hachikō used to come to the store often and they would feed him. All these last night visits may mean Hachikō was saying goodbye to people and places he knew well.[87] Haruno had one of her employees, Denzō Nishimura, run to report the death. The station sent two employees with a rickshaw to collect Hachikō's body. Newspapers all over Japan reported the death. It was also reported around the world, including Los Angeles, Paris, and Budapest.[88] Countless people were sad and upset, especially the Kobayashi's and Yaeko.[89] It is the only time in Japanese history there has been nationwide mourning for an animal.[90]

After his death, Hachikō's remains were taken to the Veterinary Medicine Laboratory of the Komaba Agriculture College, College of Agriculture of the Imperial University of Tokyo, for a necropsy.[91] He was then cremated and the ashes of his internal organs were buried in Aoyama Cemetery, Minato, Tokyo where they rest beside Professor Ueno.[92] Hachikō's pelt was preserved after his death, and his taxidermy is on display at the National Science Museum of Japan in Ueno, Tokyo.[92][93][94]

On March 9, 1935 at 8am a memorial service was held at Hachikō's bronze statue. There were many people, flowers, various offerings, and Buddhist priests.[95] At this memorial service, Kurita realized the puppy he had sent from Ōdate was Hachikō when a colleague said, "Hachi-kō originally came from Ōdate around January 11, 1924, and was raised by our former teacher Ueno Hidesaburō."[96] However, he kept this quiet until 1957.[96] Hachikō's funeral was held on March 12, at 2pm, at Ueno's grave in Aoyama Cemetery, with Hachikō's son Kuma-kō—who was about 4 years old at the time, 16 monks, flowers and condolence money. About 10,000 people visited Hachikō's statue from March 8–12. The March 12 funeral at Aoyama Cemetery had about 60 people attend.[97]

Two necropsies were performed on Hachikō. The first began at 3pm on the day he died. It determined that Hachikō died of dirofilariasis (heartworm) and old age. It also found that he had dirofilaria immitis, ascites and liver fibrosis. There were also four yakitori skewers in Hachikō's stomach, but the skewers neither damaged his stomach nor caused death. The veterinarians preserved his heart, lungs, liver, spleen, and esophagus in glass jars. These are on public display at the Yayoi campus of the Museum of the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo. Some of his intestines were placed in his grave beside Ueno.[98] Despite no damage being found to his stomach, some people insist he died from eating yakitori skewers. Other evidence is that the yakitori vendors only came in the evening and Hachikō went there in the morning and he went on bad weather days when the vendors did not come to Shibuya Station. The yakitori debate was going on at least until the 1980s.[99]

In December 2010 a second necropsy began, also at the Yayoi campus. Its results, using all modern techologies, were released in March 2011.[100] Scientists finally settled the cause of Hachikō's death; his causes of death were both terminal carcinosarcoma (cancer) and dirofilaria immitis. They also found microfilariasis (baby roundworms). These conditions were centered around his heart and lungs. They also confirmed yakitori skewers had not damaged him.[100][101][102] Each year on March 8, Hachikō is honored with a ceremony of remembrance at Shibuya Station.[103][104] In 1934 the story of Hachikō was accepted for use in a textbook for second-graders in the upcoming April 1935 school year to teach morals, kindness, and gratitude.[105][106][107] Hachikō is still revered in Japan and his story is taught to children to teach unwavering loyalty, perseverance, and faithfulness.[108]

Graves of Hachikō, Ueno, and Yaeko

[edit]

Hachikō's grave can be difficult to find. More people visit it than any other grave in Aoyama cemetery. Every day there are offerings of flowers, food, and coins; especially on March 8. The directions are:[109]

The little grave of Hachi is called “Hachi-kō no hokora” (miniature shrine of Hachi-kō). It is formerly the “aiken no hokora” (miniature shrine of beloved dogs) of the late Ueno Hidesaburō. It stands at the right front corner of the lot of Ueno Hidesaburō’s grave at Aoyama Cemetery. Aoyama Cemetery is located at 32-2, 2-chōme Minami-Aoyama, Minato ward, Tokyo. It has easy access from three subway stations of Tokyo Metro subway lines (details below). The lot number for Ueno’s grave is “1-shu, ro, 6-gō (area), 12-gawa (plot).” It is located on the left side of the street from the funeral home, on the premises of the cemetery. Coming from the funeral home, turn to the left at the street in front, and the lot is on the left side. On the opposite side stand graves of such dignitaries as the past Japanese prime ministers Hamaguchi Osachi and Inukai Tsuyoshi, and the finance minister Inoue Jun’nosuke. The lot with Ueno’s grave is enclosed by a lattice fence made of bamboo.[298] Also, just outside his grave, at the right front corner of the lattice fence, is erected the Hachi-kō Memorial Stone, about 4.5 feet in height, made of Mikage-stone (granite). The inscription reads: “Chūken Hachi-kō no hi” (Memorial Stone for the Loyal Dog Hachi-kō).[299]

— Mayumi Itoh (2017, Hachikō: Solving Twenty Mysteries about the Most Famous Dog in Japan, pages: 189-190)

Yaeko died on April 30, 1961. She had requested to be buried next to Ueno. The head of the Ueno family refused as she and Ueno were never married. After 55 years of negotiations and cutting through red tape, part of her remains were allowed to be buried next to Ueno and Hachikō, at the Shirakawa-stone lantern at the grave site in Aoyama Cemetery.[110] This ceremony occurred on May 19, 2016, with both Ueno and Sakano families present. Yaeko's name and the date of her death were inscribed on the side of his tombstone, thus fulfilling the reunion of Hachikō's family. "By putting the names of both on their grave, we can show future generations the fact that Hachikō had two keepers." Shiozawa said.[111] "To Hachikō the professor was his father, and Yaeko was his mother," Matsui added.[111]

Saitō kept Hachikō's bones and skull in his study. However, they were burned during the Tokyo Air Raid of May 25, 1945, along with his house.[112] The surviving remains of Hachikō are in four places: 1) some of his intestines at the Aoyama Cemetery with Ueno and Yaeko, 2) heart and lungs, liver and spleen, and esophagus at the Yayoi campus, 3) the mount of his pelt at the National Museum of Nature and Science, Ueno Park, Taitō ward, Tokyo, and 4) the “the Soul of the Loyal Dog Hachi-kō,” urn at Jindai Temple, Chōfu, Tokyo. In the 1960s some the intestine remains of Hachikō from the Aoyama Cemetery were moved to this Jindai Temple.[113] Just like with the making of Hachikō's bronze statue, there was a controversy in making his mounted pelt. The statue was made with his droopy ear, but his mount was made with both ears erect. The taxidemists wanted to do their best work ever, so it took 3 months to make the mount.[114]

Legacy

[edit]The story of Hachikō has captivated innumerable people worldwide. Countless visitors, Japanese and foreigners, visit his statue in Shibuya each year.[115] A Japanese entertainment company began "Day of the Idol Dog" in 2009, honoring a dog every November 11. Its first honoree was Hachikō.[116] In July 2012, photos from Hachikō's life were shown at the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum[117] in Shibuya as part of the Shin Shuzo Shiryoten (Exhibition of newly stored materials) exhibition of newly stored materials.[118] Many Hachikō-themed goods are sold, including: clear folders, tote bags, holders, note books, candies, cookies, kasutera (sponge cakes), green tea, rice crackers, pancakes, chocolates, and sauce. Hachi-kō sauce is a long-time seller manufactured by none other than the Hachiko Sauce Company. Hachikō sauce is still being made as of 2025 is considered one of the best “Worcestershire” sauces in Japan. It has three different flavors (original, semi-thick, and fruit).[119]

Every year on April 8, since 1984, the Society for the Preservation of the Loyal Dog Hachi-kō Bronze Statue holds a Hachikō Festival at Shibuya Station. It is held on April 8 instead of May 8 as that combines Hachikō's death date with Buddha's birthday, which is called the Flower Festival.[120][121]

Statues of Hachikō

[edit]

At the same time Teru Andō, who had made the plaster statue, was planning a bronze statue, a senior hired a sculptor, Ōuchi, who had designed the New Year's postcard, to create a wooden statue of Hachikō. The senior claimed Ueno's family had endorsed him handling all of Hachikō's commissions, but this was a blatant fabrication. The senior made woodblock-print postcards and had Stationmaster Yoshikawa sign them. Andō was very concerned with this fraud and asked Saitō to begin a bronze statue. Saitō was opposed to this as he felt that should only be done after Hachikō died. Saitō tried to get the senior to cancel the wood block project and join in with Andō, but the senior refused to help or commit money he had earned. This senior also hired Ōuchi to make a miniature statue. Reluctantly, Saitō agreed to the bronze project of Andō. Saitō never took advantage of Hachikō nor did he enjoy being in the spotlight.[122] Saitō and Andō began the Fund to Create the Hachi-kō Bronze Statue on January 1, 1934, with large nationwide support, including academics, professionals, and schoolchildren. Funds were even sent from Korea, which was a Japanese colony at that time,[123] as well as China, Taiwan, and America.[123][85] One of the fundraisers attracted about 3,000 people.[124] There was debate among the fund members about both the pose of Hachikō and where the statue should be located. Some wanted him sitting down with his droopy ear and others preferred standing with traditional Akita looks. Some wanted it under the eaves of Shibuya Station, which the station controlled, and others wanted it just outside the station, which Tokyo City controlled. The sitting realistic pose was chosen, partly because Andō could not make the standing pose to his satisfaction and the statue was placed just under the station's eaves.[125] The bronze statue was unveiled at 1pm on April 21, 1934 at the station to much fanfare, with the area in front of the station packed with people very tightly.[126] The unveiling occurred in the freight parking area, not the statue's eventual location in the station's front, because of lack of space in the front. Saitō led the ceremony and Hachikō was there. Ueno's granddaughter, Hisako, then 10, actually cut the ribbon to unveil the statue, which she and Saitō barely got to because of the dense crowds.[127] From the time of the unveiling of the bronze statue in April 1934 until long after Hachikō died, many people falsely claimed to have dogs sired by him, even though only one descendant of his, a son, is known, Kuma-kō, who was owned by Yoshitarō Itō. Itō had a Fox Terrier named Debbie, who was Kuma-kō's mother. Debbie died and Hachikō apparently stayed monogamous after that.[128]

In 1933 Andō began making about ten 6-inch high statues of Hachikō in a lying down posture. He kept one himself, one to Empress Dowager Sadako, one to Emperor Hirohito, and one to Empress Nagako. The rest went to his friends. The one he kept himself had its front legs partially melted in the large Tokyo air raid fires of May 25, 1945, but it was recovered. Andō and his daughter both perished in this fire.[129]

Shortly after the Marco Polo Bridge incident on July 7, 1937, the Japanese government began expansion and militarization its economy, people, and material for war. This incident is considered the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War and became part of the Pacific War, which was part of World War II. The government would requistion material for the war effort, put children as young as middle-schoolers into the work force, and censored the media. By 1943 the situation for metals was so desperate that items like zoo guard rails and memorial plaques for animals were being requisitioned. If need be animals would be euthanized so that their cage metal could be used.[130] Dogs were euthanized as they required food. Only German Shepherds were exempt because they were military dogs. Akitas were the first targets because they ate lots of food and their fur could be used for coats. At the end of World War II only 15-16 purebred Akitas were alive in Japan. If you refused to donate your pet, you were treated as a traitor. Some people were even arrested and tortured for not cooperating with the war effort.[131] As the 1944 recycling drive began, Hachikõ 's statue at Shibuya Station became a target. Saitō says people put a white sash on it and wrote “Conscript it” on the sash. At the end of 1944 the Railways Bureau informed Saitō that they were going to melt down the statue. Saitō got Transportation Vice Minister to agree to put the statue in storage.[132] The statue was taken down on October 12, 1944 amid an emotional farewell ceremony. Per the agreement, it was supposed to stay in storage. The Railways Bureau went back on the storage agreement and donated it to the war effort.[133] Many were saddened and considered this the "Second Death" of Hachikõ.[134] It was eventually melted down on August 14, 1945 in Hamamatsu,[135] one day before Emperor Hirohito announced surrender, ending World War II.[112][136] The statue became parts for locomotive machinery, not bullets as is sometimes reported.[137] Saitō was not aware of this until late 1947 because he had evacuated Tokyo for Kyoto during the war and stayed there a couple years after the war. The Japan National Tourist Organization asked him about the statue because a lot of people wanted to see it, including Americans. Saitō told them the statue was safe.[138] In late 1947 Takeshi Andō, son of Teru, sent Saitō a letter that made him very grief stricken because it informed Saitō that during the war Teru and his daughter died in the May 25, 1945 air raid, the air raid burned down his house and art works, Takeshi himself had been drafted and had served on the front lines, the plaster statue had burned in the same air raid, and that Takeshi needed Saitō's help in making a second Hachikō statue.[135][138]

Materials and money were in short supply in post-war Japan. Despite this, in late 1947 the Committee to Recreate the Hachi-kō Bronze Statue was created to build a second statue. The Japan National Tourist Organization was also influential in these efforts.[139] The officials of the Supreme Commander Allied Powers (SCAP) initially resisted these efforts because they saw Hachikō's loyalty as promoting devotion to imperialism. Eventually they realized Hachikō had nothing to do with that.[140] Despite the economic hardships of the post-war era, many common people donated money for the second statue, as well as many influential people. Many Americans had heard about the fate of the first statue and donated money.[141] Takeshi Andō began working on the new statue even though at the beginning there was not enough metal. In addition, he had no real-life model and had to rely on photographs and Saitō's measurements. Years later, Takeshi admitted he had melted down one of his father's master works that had been damaged in the war to make the second statue. The original statue's pedestal had survived the war so they used that for the new statue. Two bronze plaques describing Hachikō's provenance, one in English and one in Japanese, were attached to the pedestal.[142]

On August 15, 1948, third anniversary of Hirohito's surrender announcement, Takeshi Andō, unveiled a second statue.[143][144] Children representing England, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and the United States were there.[145] The new statue still stands and is a popular meeting spot. The Shibuya Station entrance near this statue is named Hachikō-guchi, meaning "The Hachikō Entrance/Exit", at the southeast part of the station,[133] is one of Shibuya Station's five exits. The precise spot where Hachikō waited is now marked with bronze paw prints.[146] Although Hachikō is highly revered in Japan and around the world, there are people who still disrespect him. The Shibuya statue is near a late-night party area and some people, generally young adult females, climb on top of the statue and "perform acts that attract public attention".[147] This second statue has been moved at about ten times due to construction projects, but also stays at the station.[148] In 1984 the bronze statue of Hachikõ was reunited with Ueno when the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo realized the bronze bust they had was that of Ueno and he had been Hachikō's owner, so they sent it to Shibuya Station.[120] Saitō founded the Japan Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (JSPCA) in May 1948 and served as one of its leaders until he died on September 19, 1964.[149][150] Takeshi died on January 13, 2019 at age 95.[143] The front legs and muzzle of this statue are now shiny because so many people have touched it. Takeshi is happy about this as it show many people truly care about Hachikō.[151]

Another statue is in Hachikō's hometown, in front of Ōdate Station; it was unveiled at Ōdate Train Station on July 8, 1935.[152] This statue was also melted down during the 1945 recycling efforts.[153] Fund raising for a new one began in 1962 and it was unveiled in May 1964 in front of Ōdate Station. It depicts Hachikō standing, a female laying down, and three puppies and is called "Group Statues of Akita-inu". On November 14, 1987, a solo statue of Hachikō standing was erected, just several meters from the group statue.[154][155] A stone statue of Hachikō and stone steles were erected at the Saitō family residence, his birthplace, in Ōdate in 2003. The steles describe his provenance.[156] In 2004, a new statue of Hachikō was erected in front of the Akita-inu Hall in Ōdate.[157][155][158]

After the release of the American movie Hachi: A Dog's Tale (2009), which was filmed in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, the Japanese Consulate in the United States helped the Blackstone Valley Tourism Council and the city of Woonsocket to reveal an statue of Hachikō identical to the one at Shibuya Station at the Woonsocket Depot Square, which was the location of the "Bedridge" train station featured in the movie.[159] This statue in Woonsocket was bronze and was bought on eBay. It is smaller than the one in Shibuya and its creation was not authorized. Andō had approved of Woonsocket getting a statue, but he was unaware a look-alike unapproved replica ending up being bought. An Akita-mix named Hachi stood in for Hachikō at the dedication ceremony.[160][161]

On March 9, 2015, the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo, Ueno's alma mater and workplace where he commuted every workday during his time with Hachikō, made a bronze statue depicting Ueno returning to meet Hachikō to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Hachikō's death.[162][163] The statue was sculpted by Tsutomu Ueda from Nagoya and depicts an excited Hachikō jumping up to greet his master at the end of a workday.[164] Ueno is dressed in a hat, suit, and trench coat, with his briefcase placed on the ground. Hachikō wears a studded harness as seen in his last photos.[165] In a ceremony attended by the Japanese Ambassador in October 2016, a bronze statue of Hachiko and Dr. Ueno, identical to the one on the Yayoi Campus of the University of Tokyo, was installed in Abbey Glen Pet Memorial Park in Lafayette Township, New Jersey, USA.[166][167]

List of statues of Hachikō

[edit]| Name | Location | Year | Name of Creation | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hachikō Plaster Statue I (two miniature replicas exist, one found only in 2014) | Tokyo | 1933 | Teru Andō | Burned during air raid in 1945[135][138][168][169] |

| Hachikō Miniature Lying-Down Statue | Tokyo | 1933 | Teru Andō | Presented to Empress Dowager Sadako, Emperor Hirohito, and Empress Nagako, friends, Andō kept one (two perfect statues in the same style were found in 2013 and 2014)[129][168][169] |

| Hachikō Bronze Statue I | JGR Shibuya Station Tokyo | 1934 | Teru Andō | Melted down in 1945[135][168] |

| Replica of Hachikō Bronze Statue I | JR Ōdate Station | 1935 | Melted down in 1945[153][168] | |

| Hachikō Plaster Statue II-a | JR Tsuruoka Station, Yamagata prefecture | 1947 | Takeshi Andō | “Discovered” in 2004[168][170] |

| Hachikō Plaster Statue II-b | Kagoshima City Museum of Art | 1948 | Takeshi Andō | Collected in 1978[171][172] |

| Hachikō Bronze Statue II | JR Shibuya Station | 1948 | Takeshi Andō | [143][144][168] |

| Group Statues of Akita-inu | JR Ōdate Station | 1964 | Zen’ichirō Aikawa | Hachikō, a mother dog and three puppies[154][168] |

| Hachikō Bronze Statue III | JR Ōdate Station | 1987 | Yoshio Matsuda | [154][155][168] |

| Replica of Hachikō Bronze Statue III | JR Ōdate Station, Hachikō Shrine | 1989 | Made in styrofoam, remade in bronze in 2009[168][173] | |

| Imitation of Hachikō | Fujishima Community Square | 2001 | Made in bronze[168][170] | |

| Hachikō Stone Statue and Stone Steles | Saitō Family Residence | 2003 | Birthplace of Hachikō, Ōdate[156][168] | |

| Hachikō Bronze Statue III (“Hachi-kō longing for his hometown”) | Akita-inu Hall, Ōdate | 2004 | Yoshio Matsuda | [157][155][158][168] |

| Imitation of Hachikō Bronze Statue II | Woonsocket, Rhode Island | 2012 | Bought on eBay[160][161][168] | |

| Paired Bronze Statues of Dr. Ueno and Hachi | Hisai Kintetsu Station, Tsu, Mie prefecture | 2012 | Katsuji Inagaki | A derby was added to Dr. Ueno’s head, Dec. 2016[168][174] |

| Paired Bronze Statues of Dr. Ueno and Hachi | Faculty of Agriculture, University of Tokyo, Yayoi campus | 2015 | Tsutomu Ueda | [162][163][164][168] |

| Paired Bronze Statues of Dr. Ueno and Hachi | Abbey Glen Pet Memorial Park in Lafayette Township, New Jersey | 2016 | Identical to the one on the Yayoi Campus of the University of Tokyo[166][167][171] | |

| Small Bronze Statue of Hachi | Miyashita Park, Shibuya, Tokyo | 2020 | In “Shibuya Hachi Compass”[171][175] |

Birthdays

[edit]On November 10, 2012, Google commemorated what would have been Hachikō's 89th birthday by uploading a Google Doodle that depicts the famous dog waiting by the Shibuya Station railway and holding Ueno's hat in his mouth.[9] On November 10, 2023, the Japanese people commemorated what would have been Hachikō's 100th birthday. Events included visits to the Shibuya Station, songs, and dances.[176] A holographic display of Hachikō was installed at the Akita Dog Visitor Center in Odate, Akita Prefecture, greeting guests who came by to celebrate his birth.[177]

In media

[edit]

Hachikō was the subject of the 1987 film Hachikō Monogatari (ハチ公物語, "The Tale of Hachikō") directed by Seijirō Kōyama, which told the story of his life from his birth up until his death and had spiritual reunion with his master.[178][179] Considered a blockbuster success, the film was the last big hit for Japanese film studio Shochiku Kinema Kenkyū-jo.[180] This was the highest grossing film in Japan in 1987 and received the Yamaji Fumiko Film Award.[116] Another film based on Hachikō is the 2015 Telugu film, Tommy.[181]

"Jurassic Bark" (2002), episode 7 of season 4 of the animated series Futurama has an extended homage to Hachikō, with Fry discovering the fossilized remains of his dog, Seymour. After Fry was frozen, Seymour is shown to have waited for Fry to return for 12 years outside Panucci's Pizza, where Fry worked, never disobeying his master's last command to wait for him.[182]

Hachikō is also the subject of a 2004 children's book entitled: Hachikō: The True Story of a Loyal Dog, written by Pamela S. Turner and illustrated by Yan Nascimbene.[183] Another children's book, a short novel for readers of all ages called Hachiko Waits, written by Lesléa Newman and illustrated by Machiyo Kodaira, was published by Henry Holt & Co. in 2004.[184]

In the Japanese manga One Piece, there is a similar story with a dog named ChouChou.[185]

In the video game: The World Ends with You (2007), the Hachikō statue is featured, it's referenced on several occasions. The location of Shibuya statue plays a role in the narrative of the game. The statue is featured again in the sequel: Neo: The World Ends with You (2021).[186][187]

Producer Vicki Shigekuni Wong saw the Hachikō statue while visiting Shibuya in the 1980s and was so moved by his life that after returning to the United States,[188] she adopted a Shiba Inu dog and named it Hachi. When her beloved dog, Hachikō, died at the age of 16, she decided to make a film about Hachiko, a symbol of the strong bond between dogs and humans.[189] The resulting film, Hachi: A Dog's Tale (released August 2009), is an American movie starring actor Richard Gere, directed by Lasse Hallström, about Hachikō and his relationship with an American professor and his family following the same story, but different. For example, Hachikō was a gift to professor Ueno, this part is entirely different in the American version.[190] The movie was filmed in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, primarily in and around the Woonsocket Depot Square area and also featured Joan Allen and Jason Alexander. The role of Hachi was played by three Akitas: Leyla, Chico, and Forrest. Mark Harden describes how he and his team trained the three dogs in the book: "Animal Stars: Behind the Scenes with Your Favorite Animal Actors."[191] After the movie was completed, Harden adopted Chico.[190]

Hachikō himself in media

[edit]Hachikō himself made at least two media appearances in 1934, the zenith of his notoriety after the statue unveiling. In 1994, Nippon Cultural Broadcasting in Japan was able to restore a recording of Hachikō barking, Junjō bidan Hachi-kō (Heartwarming Story of Hachi-kō), from an old 78 RPM record by Kikusui Records that had been broken into several pieces. The pieces were melded together using a laser. A huge advertising campaign ensued and on Saturday, May 28, 1994; 59 years after his death, millions of radio listeners tuned in to hear Hachikō's bark.[192] It is reported to sound like the "feeble howling of an old wolf", akin to "Wohw. Wohw. Wohw."[193] In December 1934 Hachikō made a cameo in a movie Arupusu taishō (King of the [Japan] Alps). In one scene a man is telling an audience about the information on Hachikō's bronze statue plaque. A boy is uninterested and the man asks him why. The boy, stroking Hachikō's neck, says “You come here, Mister. This is the real Hachi-kō. The Hachi-kō Bronze Statue isn’t interesting. Be kind to the real Hachi, instead.”[193]

Yaeko Sakano

[edit]

Yaeko Sakano (坂野 八重子, Sakano Yaeko),[e] often referred as Yaeko Ueno, was the unmarried partner of Hidesaburō Ueno for almost 10 years until his death in 1925. Being unmarried, she could not inherit Ueno's assets.[41] Hachikō was reported to have shown great happiness and affection towards her whenever she came to visit him. Tomokichi Kobayashi, with whom Hachikō lived for many years, reported that Hachikō only jumped for joy upon seeing: Yaeko and Ueno. She was also the person that could get him into a taxi.[75][76] Yaeko stated no other dog understood people the way Hachikō did and that he was truly gentle.[195] Yaeko died on April 30, 1961,[194] at the age of 76 and was buried at a temple in Taitō, further away from Ueno's grave, despite her requests to her family members to be buried with her partner. In 2013, Yaeko's documents, indicating that she wanted to be buried with Ueno, were found by Sho Shiozawa, who is a professor of the University of Tokyo. Shiozawa was also the president of the Japanese Society of Irrigation, Drainage, and Rural Engineering, which manages Ueno's grave at Aoyama Cemetery.[111] On November 10, 2013, which marked the 90th anniversary of the birth of Hachikō, Sho Shiozawa and Keita Matsui, a curator of the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial, felt the need of Yaeko to be buried together with Ueno and Hachikō.[196] The process began with willing consent from the Ueno and Sakano families and the successful negotiations with management of the Aoyama Cemetery.[197] However, due to regulations and bureaucracy, the process took about 2 years.[110] Shiozawa also went on as one of the organizers involved with the erection of bronze statue of Hachikō and Ueno which was unveiled on the grounds of the University of Tokyo on March 9, 2015, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Hachikō's death.[162][163]

Mystery of Hidesaburō Ueno and Yaeko Sakano's son

[edit]Hidesaburō and Yaeko were long reported as not having any children,[43] except for one mention in Yaeko's own written records on Hachikō. She writes "Hachi was a gentle dog. When he was just one year old, our son was born. Hachi was also gentle with our baby. I often found Hachi in the baby’s room and sleeping with our son. Hachi was so affectionate with our son that I sometimes tucked them into bed together. This made Hachi very happy."[198] and Professor Itoh writes "That her son was born when Hachi was one year old has never been mentioned in any document, to the knowledge of this author."[198] Kazuto Ueno, of the Society for the Preservation of the Bronze Statues of Dr. Ueno Hidesaburō and Hachi-kō, is the possible grandson of Hidesaburō. He was introduced as such at a paired statue dedication of and Ueno in Hisai, Mie in 2012.[174] He was also present at the first “Best Idol Dog” presentation in 2009.[43] He grew up in Ueno Hidesaburō’s home prefecture, Mie Prefecture There is no death record of a son of Hidesaburō and Yaeko dying young. He is the son of their once-mentioned son, Jin Ueno. It is possible that the Ueno family took this child away because he was illegitimate to give him legal protections, which was a common practice during that time. Jin grew up in Hisai, and was a "nephew" of Hidesaburō, though Hidesaburō and Yaeko were not allowed to see him. Jine became the mayor of Hisai and a member of the Mie Prefecture Assembly.[43] Jin was also the legal custodian of Hidesaburō's grave in Aoyama Cemetery. But Kazuto was born in 1937. Yaeko could have mistaken Hisako's birth in February 1924 with an earlier birth of her son. Jin was born July 31, 1912 and is old enough to be Kazuto's father. There is a 1999 TV documentary about Hachikō in which Kazuto made an appearance as Dr. Ueno’s grandson. The documentary showed a family genealogy of the Ueno family in which Jin is Hidesaburō's sole son and Kazuto as Jin’s eldest son. In this documentary Kazuto stated: “Someone once told me that my grandfather had raised his dogs as if they had their own dignity, just as human beings have a dignity.” This proves Hidesaburō and Yaeko did have a son, Jin, and he is the father of Kazuto.[43]

Helen Keller and Stevie Wonder

[edit]

Helen Keller visited Akita Prefecture in June 1937 and knew of and asked about Hachikō. She began keeping Akita's as pets and introduced them to America. She intended to visit Korea, China, and the Hachikō statue in Shibuya, but her visit was cut short by the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. So was not able to "meet" Hachikō on that trip.[199] Her first Akita, Kamikaze-Go (“divine wind”), whom she called Kami for short, was taken to meet her in Tokyo when she had to sail back to America. The first Akita given to her was Kamikaze-Go, who was the first Akita to travel overseas from Japan and the first Akita in America. He died of an distemper two months after arriving in America on November 18, 1937 and Keller was given Kamikaze-Go's brother in June 1, 1939 in Tokyo, Kenzan-Go (“steep mountain”), Go-go for short. Japan-US relations were in serious decline by then and there concern on both sides as to whether "G-go" would make it to America safely.[199][200][201][202] Keller and Go-Go were great companions from day one. Go-Go even spent his first night at Keller's home sleeping at the foot of her bed.[203] Go-go died in 1944 or 1945. After the end of World War II, many Americans brought many more Akitas, who were actually Shepherd-Akita mixes, back to America. These dogs became known as the American Akitas.[199] On August 30, 1948, she touched the re-made statue of Hachikō at Shibuya Station, just 15 days after it was unveiled.[f]

Stevie Wonder had his younger brother travel to Akita Prefecture in 2000 to find him an Akita puppy. He had an Akita when he was young and insisted on getting a Japanese Akita this time as he felt they were the real Akitas.[204]

Shibuya Ward Minibus

[edit]

In 2003, in Shibuya ward, a minibus (officially called "Shibuya-ward Community Bus") started routes in the ward, nicknamed "Hachikō-bus".[205] The buses are different colors (red, orange, blue) to denote which of the three routes they run. The buses are short and narrow to aid in navigating Shibuya's congestion. People can hear the theme song Hachikō-basu no uta (ハチ公バスのうた), the "Hachikō Bus Song", in this bus. The song service began in July 2006.The Shibuya-ward school district adopted the song and elementary schools in the area play it during lunch time.[205][206][207][208]

Similar cases

[edit]See also

[edit]- Argos – Odysseus's faithful dog in the Odyssey

- Balto – Siberian husky and sled dog (1919–1933)

- Fido – Italian dog (1941–1958)

- Greyfriars Bobby – Skye Terrier

- List of individual dogs

- Loyalty – Monument in Tolyatti, Russia

- Man's best friend – Common phrase referring to domestic dogs

- Nipro Hachiko Dome – Stadium in Ōdate, Akita, Japan

- Pet ownership in Japan

- Shep – Border Collie who lived in Fort Benton, Montana

- Stargazing Dog – Japanese manga by Takashi Murakami

- Togo – Sled dog who ran in the 1925 serum run to Nome, Alaska

Notes

[edit]- ^ Weak sources say Ueno himself bought Hachikō for ¥30, but quality sources do not support this.[19]

- ^ The straw bag was a yoko-dawara, a miniature-size kome-dawara, which is used for carrying rice with a high heat retention capacity.[22]

- ^ Itoh gives an extremely detailed account of the dates and circumstances of Hachikō's journey to Tokyo, describing train schedules, natural events, and a letter.[24]

- ^ If you add 9 years, 9 months and 15 days to Ueno's date of death you get Hachikō's date of death. Hachikō only did not commute if he was physically away from the Shibuya area or ill.[39][40]

- ^ Yaeko's original maiden name is unknown. While she often went by Yeako Ueno, she could not legally take that name nor inherit Ueno's property because they were not married. However, she was often referred to as his wife and by the surname Ueno. They were long reported to have no children, but they had a son.[43] Ueno adopted a girl named Tsuruko, birth surname unknown. Tsuruko married a man named Yasushi Sakano. Yaeko legally adopted Sakano and then legally took the surname Sakano. Therefore, she was also known by the last name Sakano.[194] Ueno's family had wanted him to marry another woman but Ueno during the wedding he snuck out the back door.[41]

- ^ Some sources report September 5, 1948.[143][146][199]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Itoh, Mayumi (2017). Hachikō: Solving Twenty Mysteries about the Most Famous Dog in Japan (Kindle). Amazon.com Kindle E-book. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-197-33-8013-9.

- ^ a b c Itoh, Mayumi (2023). Hachikō: At the Centennial of his Birth (Kindle). Amazon.com Kindle E-book. p. 7. ISBN 979-837-01-9191-6.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 103

- ^ a b "Hollywood the latest to fall for tale of Hachiko". The Japan Times. Kyodo News. June 25, 2009. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 19–23

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 23

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 19–23, 102–106, 111, 154–155

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b "Hachiko's 89th Birthday". Google Doodles. November 10, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Hachikō". Akita Club of America. January 16, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 21, 27–28, 31, 112–113

- ^ a b c "Hachikō, the Faithful Dog". Nippon.com. September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 51–53

- ^ "Kō (公)" [Kō (male)]. Kotobank.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved September 16, 2025.

人や動物の名前に付けて,親しみ,あるいはやや軽んずる気持ちを表す。

[Used after the names of people or animals to express affection or slight contempt] - ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 99–101

- ^ a b Itoh 2023, pp. 35–37

- ^ a b c Itoh 2017, p. 25

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 244

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 27

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 30

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 12

- ^ a b c d e "Hachiko: The world's most loyal dog turns 100". BBC. July 1, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 27–31, 46

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 35–44

- ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 112–114

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 35

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 53

- ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 34–35

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 53–56

- ^ "東大ハチ公物語" [The story of Hachikō and Dr. Ueno]. ハチ公と上野博士の物語 (in Japanese). University of Tokyo. Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 54–56, 77

- ^ "ハチ公 やっと博士のもとへ" [Hachiko finally reaches the professor]. 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun Digital. March 4, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ "ハチ公の飼い主 上野先生" [Hachiko's owner, Professor Ueno]. ニュースがわかるオンライン (in Japanese). News Gawakaru. December 22, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 62

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 67

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 263

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 67–69

- ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 37, 63–64, 106, 118, 180–182, 184–185, 236

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 92, 121, 164

- ^ a b c Itoh 2017, p. 73

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 42

- ^ a b c d e f Itoh 2023, pp. 240–241

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 73–74

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 75–76

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 77–79

- ^ a b c Itoh 2017, p. 81

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 79–81

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 44, 84–85

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 82–83

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 84

- ^ a b c "The Legend of Hachiko". Japan Times. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 84–87

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 91

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 261

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 84–85

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 91–93, 200

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 91–93

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 93–94

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 89

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 94

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 94–96, 100

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 68

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 110–111

- ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 98–99

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 96

- ^ Bouyet, Barbara (2002). Akita, Treasure of Japan, Volume II. Hong Kong: Magnum Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 0-9716146-0-1.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 97–100

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 100

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 100–102

- ^ Kajiwara, Naoto (1975). "The History of The Akita Dog: The Early ( 1926-1945 ) Showa Period (1926-1989 )". Shin Journal-sha: 63–71. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 103–105

- ^ Thangham, Chris V. (August 17, 2007). "Dog faithfully awaits return of his master for past 11 years". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Skabelund, Aaron Herald (September 23, 2011). "Canine Imperialism". berfrois.com. Berfrois. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 108–110, 115

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 257–258

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 115

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 115–119

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 19–20, 102, 119–121

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 121–122

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 123–124

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 124

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 126

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 132–137

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 141

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 158–159

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 159–162

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 174

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 162–164

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 167

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 165–179

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 164

- ^ "Opening of the completely refurbished Japan Gallery of National Museum of Nature and Science". The National Science Museum, Tokyo. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

In addition to the best-loved specimens of the previous permanent exhibitions, such as the faithful dog Hachikō, the Antarctic explorer dog Jiro and Futabasaurus suzukii, a plesiosaurus native to Japan, the new exhibits feature a wide array of newly displayed items.

- ^ Kimura, Tatsuo. "A History Of The Akita Dog". Akita Learning Center. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 22, 33, 166–168

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 22, 33

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 169–173

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 179–180

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 179–185

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 185–187

- ^ "Mystery solved in death of legendary Japanese dog". news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2015.

- ^ "Worms, not skewer, did in Hachiko". The Japan Times. March 4, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ American Kennel Club (listed author): Complete Dog Book: The Photograph, History, and Official Standard of Every Breed Admitted to AKC Registration, and the Selection, Training, Breeding, Care, and Feeding of Pure-bred Dogs, Howell Book House, 1985, p. 269. ISBN 0-87605-463-7.

- ^ Tremain, Ruthven (1984). The Animals' Who's Who: 1,146 Celebrated Animals in History, Popular Culture, Literature, & Lore. New York: Scribner. p. 105. ISBN 0-684-17621-1.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 149–150

- ^ オン ヲ 忘レルナ [Jinjo Elementary School Training Manual for Children” Volume 2] (in Japanese). Ministry of Education. November 22, 1934. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Skabelund, Aaron (2011). Empire of Dogs. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 1, 6, 88. ISBN 978-0801450259.

- ^ Hassler, David (2002). "The Prayer Wheel". Prairie Schooner. 76 (1): 109. JSTOR 40636036. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 189–190

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 191

- ^ a b c "Remains of Hachiko master's wife reinterred with husband, famously loyal dog". Mainichi Daily News. May 20, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 215

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 191–195

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 197–207

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 318

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 308

- ^ "Shibuya City / Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum". Shibuya City. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ Ohmoro, Kazuya (June 16, 2012). "Shibuya museum showcases last photo of loyal pooch Hachiko". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 115–116, 312

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 231–232

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 246

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 126–127

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 127–131

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 139

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 131–132

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 143–145

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 143–144

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 147, 169, 309–311

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 152

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 209–210

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 210, 213–215, 270–272

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 210

- ^ a b Robertson, Jennifer (2018). "Robot Reincarnation: Rubbish, Artefacts, and Mortuary Rituals". Consuming Life in Post-Bubble Japan: A Transdisciplinary Perspective. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 165. doi:10.2307/j.ctv56fgjm.12. ISBN 978-94-6298-063-1. JSTOR j.ctv56fgjm.12.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 210–212

- ^ a b c d Itoh 2017, pp. 212–213, 217

- ^ Toland, John (2003). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1939-1945. New York: The Modern Library. pp. 838, 849. ISBN 9780812968583.

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 174

- ^ a b c Itoh 2017, pp. 215–217

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 219

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 219–222

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 222

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 222–223

- ^ a b c d "Sculptor of faithful dog Hachiko's statue dies at 95". Kyodo News. March 9, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ a b Newman, Lesléa (2004). Hachiko Waits. New York: Macmillan. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-0-8050-7336-2. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 223–225

- ^ a b "Helen Keller". Akita Club of America. January 17, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Cybriwsky, Roman (1988). "Shibuya Center, Tokyo". Geographical Review. 78 (1): 59–60. Bibcode:1988GeoRv..78...48C. doi:10.2307/214305. JSTOR 214305. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 227

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 247

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 76

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 330

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 152–154

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 217

- ^ a b c Itoh 2017, pp. 227–231

- ^ a b c d "Akita Dog Museum in Odate". Japan Travel. July 23, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 277–279

- ^ a b "Akita Dog Museum". Visit Akita. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 279

- ^ "Sights ~ Hachikō statue ~ Woonsocket". iheartrhody.com. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 285–288

- ^ a b Itoh 2023, pp. 189–190

- ^ a b c Paje, Jessica A. (April 21, 2015). "Hachiko Statue University of Tokyo". Japan Travel. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Hachiko, Japan's most loyal dog, finally reunited with owner in heartwarming new statue in Tokyo". Sora News 24. February 11, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 282

- ^ "Hachiko Statue University of Tokyo – Japan Tourism Guide and Travel Map". Japan Travel. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Dimon, JoAnn (January 7, 2017). "Hachi-Ko Unveiled In NJ Pet Cemetery". Akita Club of America. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ a b Obernauer, Ed (October 10, 2016). "Japanese ambassador dedicates local memorial". New Jersey Herald. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Itoh 2017, p. 293

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 301–305

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 295–298

- ^ a b c Itoh 2023, pp. 201–202

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 198

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 277–278

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 279, 284–285

- ^ Itoh 2023, pp. 252–253

- ^ Tamura, Hikoshi (November 13, 2023). "Events celebrating loyal dog Hachiko's 100th birthday held in north Japan city". Mainichi Shimbun. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Yoshida, Koichi (November 13, 2023). "Akita celebrates 100 years since birth of Hachiko with hologram". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ "過去興行収入上位作品" [Past top-grossing films] (in Japanese). Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ "邦画興行収入ランキング" [Japanese film box office ranking]. SF MOVIE DataBank (in Japanese). General Works. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Ciecko, Anne Tereska (2006). Contemporary Asian Cinema: Popular Culture in a Global Frame. Oxford: Berg Publishers. pp. 194–195. ISBN 1-84520-237-6.

- ^ "Tommy Telugu Movie Review, Rating". APHerald [Andhra Pradesh Herald]. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Matthew (August 1, 2022). "'Futurama' writer on lessons of 'Jurassic Bark,' one of the most devastating half-hours of TV ever made". Syfy. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Turner, Pamela S. Hachikō: The True Story of a Loyal Dog. Publishers Weekly. ISBN 978-0-618-14094-7. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ "Hachiko Waits". lesleakids.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Chou-Chou". Behind The Voice Actors. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Jupiter. The World Ends with You (Nintendo DS). Square Enix.

Shiki: You know it. Hey, if we make it through this...let's meet up in the RG. You, me, and Beat. You might not recognize me, so...I know! I'll bring Mr. Mew with me. We can be a team again!

- ^ Jupiter. The World Ends with You (Nintendo DS). Square Enix.

Shiki: Neku? See you on the other side. You know the meeting place. Hachiko! / Neku: Heh. It's a date.

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 308–309

- ^ "Outdoor Movie Screening: HACHI - A Dog's Tale". Japan Foundation Los Angeles. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ a b Itzkoff, Dave (September 24, 2010). "Film Has Two Big Names and a Dog, but No Big Screens". The New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ Ganzert, Robin; Anderson, Allen; Anderson, Linda; Becker (Foreword), Marty (Foreword) (2014). Animal Stars: Behind the Scenes with Your Favorite Animal Actors (Hardcover) (1st ed.). New World Library. pp. 296 pages. ISBN 978-1608682638. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Reid, T.R. (June 3, 1994). "Japan's Hero Barks from Beyond the Grave". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 146–147

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, p. 70

- ^ Itoh 2017, pp. 260–261

- ^ "In love and death". The Nation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Itoh 2023, p. 233

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 260–263

- ^ a b c d Itoh 2017, pp. 321–325

- ^ "Deep and Beautiful Bond between Helen Keller and Akita Dogs". Akita-Inu News. October 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- ^ Blazeski, Goran (February 13, 2017). "Helen Keller had a Japanese Akita dog named Kamikaze-go; She was the first to bring an Akita dog to the United States". The Vintage News. Retrieved September 17, 2025.

- ^ Ogasawara, Ichiro. "Helen Keller and Akitas". Akita Learning Center. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ Gibeault, Stephanie. "Hellen Keller, Accomplished & Inspirational Icon, Was a Lifelong Dog Lover". American Kennel Club. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Itoh 2017, p. 326

- ^ a b Itoh 2017, pp. 146–147, 312–314

- ^ "コミュニティバス「ハチ公バス」が28日から運行開始" [Community bus "Hachiko Bus" begins operation on the 28th] (in Japanese). Shibukei. March 1, 2003. Retrieved September 16, 2025.

- ^ "Hachiko Bus". Kanpai Japan. March 4, 2025. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

- ^ "Hachiko Bus". Fujikyu. Retrieved September 23, 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Itoh, Mayumi (2013). Hachi: The Truth of the Life and Legend of the Most Famous Dog in Japan. Amazon.com Kindle E-book. ASIN B00BNBWDQ4.

- Lifton, Betty Jean (2012). Taka-chan and I: A Dog's Journey to Japan. NYR Children's Collection. ISBN 978-1590175026.

- Ormeron, Anastasia (2021). Hachi&Friends. Amazon.com. ASIN B0921HP6MG.

- Skabelund, Aaron Herald (2011). Empire of Dogs: Canines, Japan, and the Making of the Modern Imperial World. Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute. Columbia University. ISBN 978-0-8014-5025-9.

- Turner, Pamela S. (2004). Hachiko: The True Story of a Loyal Dog. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618140947.

External links