Greenwood, Mississippi

Greenwood, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Howard Street in Greenwood | |

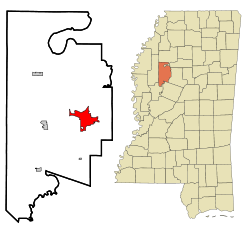

Location of Greenwood, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 33°31′07″N 90°12′02″W / 33.51861°N 90.20056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Leflore |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kendrick Cox (D)[1][2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 12.69 sq mi (302.87 km2) |

| • Land | 12.34 sq mi (301.95 km2) |

| • Water | 0.36 sq mi (0.92 km2) |

| Elevation | 128 ft (39 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 14,490 |

| • Density | 1,174.71/sq mi (453.56/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 38930, 38935 |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-29340 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403757[4] |

| Website | www |

Greenwood is a city in and the county seat of Leflore County, Mississippi, United States.[5] It is located approximately 96 miles north of the state capital, Jackson, at the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, Memphis, Tennessee is and 130 miles to its north. As of to the 2010 census, the population was 15,205. It is the principal city of the Greenwood Micropolitan Statistical Area.

The first European-American settlement in the area was established in 1834 next to the Yazoo River. A nearby settlement was founded by Chief Greenwood Leflore. The city was incorporated as "Greenwood" in 1844. It became a center of cotton planting in the 19th century, as it is located in the fertile Mississippi delta, and became a port for shipping cotton to markets along the Mississippi. Railroads built in the 1880s bolstered the local economy, especially the cotton business. In the first half of the 20th century, Cotton growing and processing became largely mechanized, reducing the need for sharecroppers and farmerworkers. Later in the 20th century, some farmers shifted to corn and soybeans.

Sally Humphreys Gwin planted 1,000 oak trees along the city's Grand Boulevard. Stokely Carmichael gave his "Black Power" speech in Greenwood in 1966.

History

[edit]

European settlement

[edit]The first settlement by European-Americnas in the area, next to the Yazoo River, was a trading post founded in 1834.[6]: 7 [7] Three miles up the river was another settlement founded by Chief Greenwood Leflore called Point Leflore. Soon an exchange of some parcels of land were made by Leflore for a commitment from the townsmen to maintain roads to the hilly area to the east and to some more established settlements to the northwest.[8]

The settlement was incorporated as "Greenwood" in 1844, named after the chief. During this period, the city began producing a crop much in demand, cotton, due its fertile location in the Mississippi delta's alluvial plain near the interseciton of the Tallahatchie and the Yalobusha rivers, which combine to form the Yazoo. The city became as a shipping point for cotton to markets in New Orleans, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Memphis, Tennessee, and St. Louis, Missouri.[9]

The construction of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad and the Georgia Pacific Railway through the city in the 1880s revitalized the local economy[6]: 8 and shortened transportation time to markets. Along the banks of the Yazoo, the city's Front Street became a hub for cotton factors and related businesses, and was nicknamed "Cotton Row".

20th century

[edit]Business was brisk into the 1940s except for during the boll weevil infestation in the early 20th century. A sign seen on the city's bridge over the Yazoo river read "World's Largest Inland Long Staple Cotton Market". Growing and processing cotton became mechanized in the first half of the 20th century, and thousands of tenant farmers, farmworkers and sharecroppers in the area were displaced. Later in the 20th century, as textile manufacturing moved out of the U.S., some local farmers began to grow corn and soybeans for animal feed instead of cotton.[10]

The U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the Garden Clubs of America have called city's Grand Boulevard one of America's 10 most beautiful streets. Sally Humphreys Gwin, a founder of the Greenwood Garden Club, planted 1,000 oak trees along the Grand Boulevard. In 1950, Gwin received a citation from the National Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution for her work in the conservation of trees.[11][12]

Activist Stokely Carmichael notably gave his "Black Power" speech during a March Against Fear rally which was held in Greenwood on June 16, 1966.[13]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.5 square miles (25 km2), of which 9.2 square miles (24 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.78 km2) is water. [citation needed]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Greenwood, Mississippi (Greenwood–Leflore Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

85 (29) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.9 (23.3) |

76.7 (24.8) |

82.8 (28.2) |

86.8 (30.4) |

91.7 (33.2) |

95.0 (35.0) |

97.9 (36.6) |

98.8 (37.1) |

96.0 (35.6) |

89.9 (32.2) |

81.8 (27.7) |

75.7 (24.3) |

99.8 (37.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.2 (12.3) |

58.8 (14.9) |

67.2 (19.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

82.9 (28.3) |

89.1 (31.7) |

91.5 (33.1) |

91.9 (33.3) |

87.3 (30.7) |

77.3 (25.2) |

65.7 (18.7) |

57.1 (13.9) |

74.8 (23.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.4 (6.9) |

48.3 (9.1) |

56.1 (13.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

72.3 (22.4) |

79.0 (26.1) |

81.5 (27.5) |

81.1 (27.3) |

75.6 (24.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

47.1 (8.4) |

64.0 (17.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 34.7 (1.5) |

37.9 (3.3) |

45.1 (7.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

61.7 (16.5) |

68.8 (20.4) |

71.6 (22.0) |

70.4 (21.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

52.4 (11.3) |

41.9 (5.5) |

37.0 (2.8) |

53.2 (11.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.6 (−8.6) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

35.8 (2.1) |

46.5 (8.1) |

58.6 (14.8) |

63.9 (17.7) |

61.9 (16.6) |

48.0 (8.9) |

33.9 (1.1) |

25.7 (−3.5) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−4 (−20) |

15 (−9) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

49 (9) |

53 (12) |

52 (11) |

35 (2) |

27 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

2 (−17) |

−4 (−20) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.52 (115) |

5.04 (128) |

4.76 (121) |

5.82 (148) |

4.44 (113) |

3.74 (95) |

3.82 (97) |

3.21 (82) |

3.83 (97) |

3.41 (87) |

3.86 (98) |

5.33 (135) |

51.78 (1,315) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 107.4 |

| Source: NOAA[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 308 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,055 | 242.5% | |

| 1900 | 3,026 | 186.8% | |

| 1910 | 5,836 | 92.9% | |

| 1920 | 7,793 | 33.5% | |

| 1930 | 11,123 | 42.7% | |

| 1940 | 14,767 | 32.8% | |

| 1950 | 18,061 | 22.3% | |

| 1960 | 20,436 | 13.1% | |

| 1970 | 22,400 | 9.6% | |

| 1980 | 20,115 | −10.2% | |

| 1990 | 18,906 | −6.0% | |

| 2000 | 18,425 | −2.5% | |

| 2010 | 15,205 | −17.5% | |

| 2020 | 14,490 | −4.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 3,646 | 25.16% |

| Black or African American | 10,198 | 70.38% |

| Native American | 7 | 0.05% |

| Asian | 154 | 1.06% |

| Other/Mixed | 276 | 1.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 209 | 1.44% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 14,490 people, 4,924 households, and 2,793 families residing in the city.

2010 census

[edit]At the 2010 census,[18] there were 15,205 people and 6,022 households in the city. The population density was 1,237.7 inhabitants per square mile (477.9/km2). There were 6,759 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 30.4% White, 67.0% Black, 0.1% Native American, 0.9% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, <0.1% from other races, and 0.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.1% of the population.

Among the 6,022 households, 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.8% were married couples living together, 29.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.6% were non-families. 32.5% of all households were made up of individuals living alone and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.16.

Arts and culture

[edit]Mississippi Blues Trail markers

[edit]

Radio station WGRM on Howard Street was the location of B.B. King's first live broadcast in 1940. On Sunday nights, King performed live gospel music as part of a quartet.[19] In memory of this event, the Mississippi Blues Trail has placed its third historic marker in this town at the site of the former radio station.[20][21] Another Mississippi Blues Trail marker is placed near the grave of the blues singer Robert Johnson.[22] A third Blues Trail marker notes the Elks Lodge in the city, which was an important black organization.[23] A fourth Blues Trail marker was dedicated to Hubert Sumlin that is located along the Yazoo River on River Road. [24]

Government

[edit]Greenwood is governed under a city council form of government, composed of council members elected from seven single-member wards and headed by a mayor, who is elected at-large.

In 2025, Democrat Kenderick Cox defeated incumbent mayor Carolyn McAdams, who had been serving since 2009.[25][26][27]

Education

[edit]Greenwood Leflore Consolidated School District (GLCSD) operates public schools. Previously the majority of the city was in Greenwood Public School District while small portions were in the Leflore County School District.[28] These two districts consolidated into GLCSD on July 1, 2019.[29] Greenwood High School is the only public high school in Greenwood. As of 2014, the student body is 99% black. Amanda Elzy High School, outside of the Greenwood city limits, was formerly of the Leflore County district. It was recently taken over by the State of Mississippi for poor performance as a result of deficient leadership.

Pillow Academy, a private school, is located in unincorporated Leflore County, near Greenwood.

Delta Streets Academy, a newly founded private school located in downtown Greenwood, has an enrollment of nearly 50 students. It has continued to increase enrollment.

St. Francis Catholic School, run by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson, provides classes from kindergarten through sixth grade.[30]

In addition, North New Summit School provides educational services for special-needs and at-risk children from kindergarten through high school.

Media

[edit]Newspapers, magazines and journals

[edit]Television

[edit]AM/FM radio

[edit]- WABG, 960 AM (blues)

- WGNG, 106.3 FM (hip-hop/urban contemporary)

- WGNL, 104.3 FM (urban adult contemporary/blues)

- WGRM, 1240 AM (gospel)

- WGRM-FM, 93.9 FM (gospel)

- WMAO-FM, 90.9 FM (NPR broadcasting)

- WKXG, 92.7 FM (Country music) KIX-92.7

- WYMX, 99.1 FM (classic rock)

Filming location

[edit]Nightmare in Badham County (1976), Ode to Billy Joe (1976), and The Help (2011) were filmed in Greenwood.[31] The 1991 movie Mississippi Masala was also set and filmed in Greenwood.[32]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Railroads

[edit]Greenwood is served by two major rail lines. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Greenwood, connecting New Orleans to Chicago from Greenwood station.

Air transportation

[edit]Greenwood is served by Greenwood–Leflore Airport (GWO) to the east, and is located midway between Jackson, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee. It is about halfway between Dallas, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia.

Highways

[edit]- U.S. Route 82 runs through Greenwood on its way from Georgia's Atlantic coast (Brunswick, Georgia) to the White Sands of New Mexico (east of Las Cruces).

- U.S. Route 49 passes through Greenwood as it stretches between Piggott, Arkansas, south to Gulfport.

- Other Greenwood highways include Mississippi Highway 7.

Notable people

[edit]- Valerie Brisco-Hooks, Olympic athlete[33]

- C. C. Brown, professional football player[34]

- Nora Jean Bruso, blues singer and songwriter[35]

- Louis Coleman, Major League Baseball pitcher[36]

- Byron De La Beckwith, white supremacist, assassin of civil rights leader Medgar Evers[37]

- Carlos Emmons, professional football player[38]

- Betty Everett, R&B vocalist and pianist[39]

- James L. Flanagan, electrical engineer and speech scientist

- Alphonso Ford, professional basketball player[40]

- Webb Franklin, United States congressman[41]

- Morgan Freeman, actor[42]

- Jim Gallagher, Jr., professional golfer[43]

- Bobbie Gentry, singer/songwriter[44]

- Sherrod Gideon, professional football player[45]

- Gerald Glass, professional basketball player

- Guitar Slim, blues musician[46]

- Lusia Harris, basketball player[47]

- Endesha Ida Mae Holland, American scholar, playwright, and civil rights activist

- Dave Hoskins, professional baseball player

- Kent Hull, professional football player[48]

- Tom Hunley, ex-slave and the inspiration for the character "Hambone" in J. P. Alley's syndicated cartoon feature, Hambone's Meditations[49]

- Robert Johnson, blues musician[42]

- Jermaine Jones, soccer player for the New England Revolution and United States national team[50]

- Cleo Lemon, Toronto Argonauts quarterback[51]

- Walter "Furry" Lewis, blues musician[52]

- Bernie Machen, president of the University of Florida[53]

- Della Campbell MacLeod (ca. 1884 – ?), author and journalist

- Paul Maholm, baseball pitcher[54]

- Matt Miller, baseball pitcher[55]

- Mulgrew Miller, jazz pianist[56]

- Juanita Moore, actress[57]

- Carrie Nye, actress[58]

- W. Allen Pepper Jr., US federal judge[59]

- Fenton Robinson, blues singer/guitarist[60]

- Laverne Smith, NFL player

- Tonya Stewart, actress[61]

- Hubert Sumlin, blues guitarist[62]

- Donna Tartt, novelist[63]

- James K. Vardaman, Mississippi governor, senator, and white supremacist

- Charlie Wells, mystery writer, author of Let the Night Fall (1953) and The Last Kill (1955)

- Willye B. White, Olympic athlete[64]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "New Leadership Ushers in Historic Change in Greenwood and Clarksdale". Delta Daily News. Retrieved July 1, 2025.

- ^ Corder, Frank (June 5, 2025). "Democrats have good night in Mississippi mayor elections". Magnolia Tribune. Retrieved July 1, 2025.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Greenwood, Mississippi

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Donny Whitehead; Mary Carol Miller (September 14, 2009). Greenwood. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6786-0. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ Kalich, Tim (April 20, 1983). ""Accounts differ on settling of Williams Landing"". The Greenwood Commonwealth. p. 12. Retrieved July 12, 2025.

- ^ Smith, Frank E. (1954). The Yazoo River. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 57-58. ISBN 0-87805-355-7

- ^ "Greenwood, Mississippi | Advisory Council on Historic Preservation". www.achp.gov. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford. "Mississippi Farmers Trade Cotton Plantings for Corn", The New York Times, May 5, 2009

- ^ "NewspaperArchive® - Genealogy & Family History Records". Newspaperarchive.com. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Mario Carter. Mississippi Off the Beaten Path[permanent dead link], GPP Travel, 2007.

- ^ Mitchell, Jerry (June 16, 2023). "On this day in 1966". Mississippi Today. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Greenwood Leflore AP, MS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". Data.census.gov. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "Greenwood Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Cloues, Kacey. "Great Southern Getaways - Mississippi" (PDF). Atlantamagazine.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 25, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ^ "Historical marker placed on Mississippi Blues Trail". Associated Press. January 25, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ^ "Film crew chronicles blues markers" (PDF). The Greenwood Commonwealth. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ Widen, Larry. "JS Online: Blues trail". Jsonline.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- ^ "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". Msbluestrail.org. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- ^ "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". Msbluestrail.org. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- ^ Edwards, Kevin (June 5, 2025). "Cox elected mayor; incumbent McAdams concedes". Greenwood Commonwealth.

- ^ "Greenwood General Election Results: Cox defeats McAdams". The Greenwood Commonwealth. June 3, 2025.

- ^ Edwards, Kevin (April 22, 2025). "Cox wins Democratic nomination for Greenwood mayor". The Greenwood Commonwealth. Retrieved June 5, 2025.

- ^ "SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Leflore County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "School District Consolidation in Mississippi Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Professional Educators. December 2016. Retrieved on July 2, 2017. Page 2 (PDF p. 3/6).

- ^ "Home". St. Francis Catholic School. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Barth, Jack (1991). Roadside Hollywood: The Movie Lover's State-By-State Guide to Film Locations, Celebrity Hangouts, Celluloid Tourist Attractions, and More. Contemporary Books, p. 169. ISBN 9780809243266.

- ^ "Mississippi Masala (1991) Filming & Production". IMDb. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Mike Celizic (February 11, 1985). "Stardom Comes too Slowly for Speedster". The Record. p. s09.

- ^ "C.C. Brown". Detroit Lions. Archived from the original on May 26, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Richard Skelly. "Nora Jean Bruso | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Louis Coleman Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ "A Little Abnormal: The Life of Byron De La Beckwith". Time. July 5, 1963. Archived from the original on April 5, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Football Signings in the Mid-South". The Commercial Appeal. February 7, 1991. p. D5.

- ^ "Betty Everett, 61, of 'The Shoop Shoop Song'". New York Times. August 23, 2001. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Bryan Crawford (October 29, 2009). "Ford left huge legacy in Euroleague basketball". Greenwood Commonwealth.

- ^ "Franklin, William Webster, (1941 - )". U.S. Congress. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "Carl Small Town Center Continues Making a Difference in the Delta". US Fed News. December 4, 2013.

- ^ Bill Burrus (July 19, 2012). "A hectic week for golfing Gallaghers". Greenwood Commonwealth.

- ^ John Howard (October 10, 2001). Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. University of Chicago Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-226-35470-5.

- ^ "Sherrod Gideon". TheProFootballArchives. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Scott Stanton (September 1, 2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Gallery Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7434-6330-0.

- ^ David Kenneth Wiggins (2010). Sport in America: From Colonial Leisure to Celebrity Figures and Globalization. Human Kinetics. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-4504-0912-4.

- ^ Sal Maiorana (January 2005). Memorable Stories of Buffalo Bills Football. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-58261-963-7.

- ^ "Mississippi Slave Narratives from the WPA Records". MSGenWeb. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Filip Bondy (April 27, 2010). Chasing the Game: America and the Quest for the World Cup. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-306-81905-6.

- ^ "Cleo Lemon". Nfl.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Paul Oliver (September 27, 1984). Songsters and Saints: Vocal Traditions on Race Records. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-26942-1.

- ^ "The President". University of Florida. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Paul Maholm Stats". Mlb.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ "Matt Miller Stats". Mlb.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Bob Doerschuk (2001). 88: The Giants of Jazz Piano. Backbeat Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-87930-656-4.

- ^ "Juanita Moore dies at 99; 'Imitation of Life' actress earned Oscar nod". Los Angeles Times. January 2, 2014.

- ^ Max Apple (1976). Mom, the Flag, and Apple Pie: Great American Writers on Great American Things. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-385-11459-2.

- ^ The Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory. Vol. 10. LexisNexis. 1996. p. 1135. ISBN 9781561601783.

- ^ Nigel Williamson; Robert Plant (April 2, 2007). The rough guide to the blues. Rough Guides. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-84353-519-5.

- ^ Bob McCann (2010). Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. McFarland. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-7864-5804-2.

- ^ Jas Obrecht (2000). Rollin' and Tumblin': The Postwar Blues Guitarists. Miller Freeman Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-87930-613-7.

- ^ Tracy Hargreaves (September 1, 2001). Donna Tartt's The Secret History: A Reader's Guide. Continuum. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8264-5320-4.

- ^ Martha Ward Plowden (January 1996). Olympic Black Women. Pelican Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4556-0994-9.