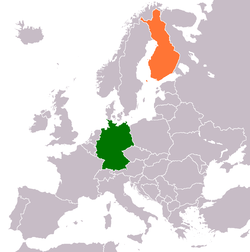

Finland–Germany relations

| |

Germany |

Finland |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Germany, Helsinki | Embassy of Finland, Berlin |

Finland–Germany relations are the bilateral relations between the Finland and Germany. Both countries are part of the European Union, are signatories of the Schengen Agreement, and are members of the eurozone and NATO. Germany fully supported Finland's application to join NATO, which resulted in membership on 4 April 2023.[1]

History

[edit]

Frankish era

[edit]The interaction between Finns and Germans can be traced back to the Viking Age, as Viking swords manufactured in the Carolingian Empire have been discovered in Finland.[2]

The Kingdom of Sweden 1100-1809

[edit]The authority of the Kingdom of Sweden became established in Finland from the 12th century onward. Sweden founded Swedish provinces in the Finnish territories. At that time, Finland was not known as a distinct concept but rather referred to as the Eastern Land of the Swedish Realm.[3]

During the Swedish rule, chartered towns with the right to engage in international trade were established in Finland. Turku and Vyborg became major commercial centers. German merchants settled in both cities, where they rose to prominence as leading burghers, becoming the most influential traders in Finland’s largest urban centers.[3]

Relations between Finland and the Holy Roman Empire were close. Finland’s trade was oriented toward the cities of the Empire and the Hanseatic League. Members of the Finnish nobility and clergy pursued studies at German universities.[3]

Sweden, Norway, and Denmark formed the Kalmar Union in 1397 as a counterbalance to the growing economic power of the Hanseatic League. The purpose of the Union was to promote internal markets and strengthen mutual security cooperation among the Nordic kingdoms.[3]

The Kalmar Union collapsed due to internal power struggles and was dissolved when Gustav Vasa ascended the Swedish throne. Sweden subsequently founded the city of Helsinki, intended to compete with Tallinn, a member city of the Hanseatic League.[3]

Vyborg evolved into the most German-influenced city in Finland. It has been characterized as architecturally reminiscent of Lübeck, reflecting the significant role played by trade families of German origin in the city’s development.[4]

In the 17th century, Sweden launched wars along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, conquering several German cities and territories. Finnish soldiers, known as “hakkapeliittas,” took part in these Swedish campaigns.[5][6]

Throughout the 18th century, Germany remained an important trading partner for Finland, continuing a centuries-long cooperation within the Baltic region.[3]

The Grand Duchy of Finland 1809-1917

[edit]Sweden lost Finland during the Finnish War of 1808–1809. The conflict was connected to the Napoleonic Wars. Sweden refused to join the Continental System against the United Kingdom, which led France, Denmark-Norway, and the Russian Empire to declare war on Sweden. As a result, Sweden found itself engaged in a two-front war.[4]

In 1809, Emperor Alexander I of Russia transformed Finland into an autonomous Grand Duchy. Thereafter, Finland’s trade expanded both toward Russia and Britain.[4]

Germany retained its prominent position among the Finnish educated classes and intelligentsia. Finns continued to seek scientific, artistic, and cultural instruction from Germany. Johan Vilhelm Snellman, the national philosopher of Finland, became acquainted with German philosophy at the University of Berlin (Humboldt University) during the years 1840–1841.[4][7][8]

German culture had a significant influence on Finland during the 19th century, particularly in the areas of urban life and education. Helsinki’s elevation to the status of Finland’s capital in 1812 brought with it a German-speaking population that played a central role in the city’s development. Carl Ludvig Engel was the main architect in Finland. The German language was, after Swedish and Russian, among the most important minority languages, and families of German origin held leading positions in commerce, education, and cultural institutions both in Helsinki and in Vyborg. German influences were also evident in literature, Romanticism, and the formation of national consciousness, although toward the end of the 19th century the role of the German language diminished in administration and education.[9][10]

German cultural impact extended into literature, Romanticism, and the shaping of nationalist ideas. However, towards the late 19th century, the status of the German language diminished in both administration and education as Finnish nationalism and the Finnish language rose in prominence. German influences were part of a broader European cultural exchange that contributed to Finnish national identity and culture during the 19th century.[11][12]

Specifically, German influence was strong in music and academia; prominent Finnish musicians studied in Germany, adopting German musical styles and educational models which shaped the Finnish music scene and institutions. Individuals such as Fredrik Pacius and Richard Faltin were key advocates of German culture in Finland, influencing academic and musical developments. German was also the main foreign language studied, and many guest lecturers at the Imperial Alexander University came from Germany, a leader in philosophy, human sciences, and natural sciences at the time.[13][10]

In Finland, German immigrants settled in the country. Among them was Heinrich Georg Franz Stockmann, who founded the Stockmann department store in 1862.[14]

The First World War began in 1914. The Grand Duchy of Finland, which was part of the Russian Empire, was allied with the United Kingdom and France, forming part of the Allies of World War I. The German Empire, Austria-Hungary, and Italy belonged to the Central Powers.[3]

Russia feared that German forces might attempt a landing on the Finnish coast. Fortification work was initiated along the Finnish shoreline, but the events of the First World War did not extend to Finland itself.[15]

In the midst of the war, in 1917, Russia experienced major strikes, mass demonstrations, and widespread unrest. Emperor Nicholas II of Russia decided to abdicate as a result of the February Revolution. The Russian Empire collapsed, and a bourgeois Russian Republic was established in its place. The Communist Revolution began in October, overthrowing the republic and giving rise to Soviet Russia. Finland declared itself independent in December 1917.[3]

The Republic of Finland

[edit]Relations between both nations began after the German Empire recognised the newly independent Finnish state on January 4, 1918. In the ensuing Finnish Civil War, Germany played a prominent role siding with the White Army and training Finnish Jägers.[16] In one of the decisive battles of the war, German troops took Helsinki in April 1918.[17]

After the Finnish Civil War, a treaty was concluded between Finland and the Germany Empire that granted significant economic advantages to Germany. The Finnish White government initiated the Finnish Kingdom project. The Finnish Parliament elected Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse, the brother-in-law of German Emperor Wilhelm II, as Crown Prince and future King of Finland. Prince Frederick was on his way to Finland when he learned, while in Estonia, that the German Empire had been overthrown. As a result, he turned back and never arrived in Finland. Finland became a republic in 1919.[3][18]

Finland’s trade with the Weimar Republic in the 1920s was a significant part of Finland’s foreign commerce. The Weimar Republic was Germany’s form of government from 1919 to 1933, and Finland’s trade relations with Germany became especially important after trade between Finland and Russia nearly came to a halt. During the 1920s, Finland imported grain primarily from Russia and Germany, and the major export goods were wood-processing products, which made up about 90% of exports in the 1920s. Thus, forestry industry exports to Germany were substantial.[19][20]

During World War II, the secret protocol in Molotov–Ribbentrop pact enabled the Winter War (1939–40), a Soviet attack on Finland. Finland and Nazi Germany were "co-belligerents" against Soviet Union during the Continuation War (1941–44), but a separate peace with Soviet Union led to the Finnish-German Lapland War (1944–45).

Germany was divided after the Second World War into West Germany and East Germany. West Germany joined the EEC and NATO, becoming part of the Western bloc, whereas East Germany became a member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the Warsaw Pact, forming part of the Eastern bloc.[3]

After the Second World War, Finland continued its policy of neutrality, which it had pursued since 1935. During the Cold War, Finland’s social system was based on democracy and a market economy.[3]

Finland recognised both the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic (West and East Germany) in 1972 and it established diplomatic relations with East Germany in July 1972 and with West Germany in January 1973.[21] The two Germanys were reunified in 1990, giving rise to present-day Germany.[3]

The EEC Free Trade Agreement of Finland, concluded in 1973 and entering into force at the beginning of 1974, increased trade between Finland and the European Economic Community (including West Germany). On the basis of the agreement, the gradual abolition of most tariffs on industrial products by the end of 1977 improved Finland’s access to Western European markets, which boosted trade and investment opportunities with West Germany. This agreement was a significant part of Finland’s Western integration, strengthening trade relations with West Germany without EEC membership. It had a positive impact on the growth of Finland’s foreign trade volume toward Western European countries and increased direct investment in Finland from Western Europe. The agreement did not cover agricultural products, but it was a significant step in strengthening Finland’s economic ties with the West in the 1970s.[22][23][24]

Finland became a member of the European Union in 1995 and joined the Eurozone with Germany in 1999. Finland’s decision to join the EU strengthened the relations between Finland and Germany. In July 2022, Germany fully approved Finland's application for NATO membership.[3][25]

Trade

[edit]Traditionally, Finland’s principal export articles to Germany have included forest industry products - paper, cardboard, and pulp - alongside telecommunications equipment, motor vehicles, and iron and steel. The most significant import items have been motor vehicles as well as machinery and equipment.[26]

Approximately 400 Finnish companies operate subsidiaries or branch offices in Germany. Traditional players include Nokia, Wärtsilä, Kone, Stora Enso, UPM Kymmene, and Outokumpu. The most relevant sectors for Finland in Germany are IT and digitalization, bioeconomy, and environmental technology markets. German ports play a central role in transit traffic passing through Finland. Access to the German market is challenging, yet success in Germany serves as a guarantee of quality and expertise. Furthermore, cooperation as a partner or subcontractor to a German company offers entry into global corporate networks.[26]

About 350 German parent companies maintain subsidiaries in Finland, mainly in the pharmaceutical and logistics sectors. The most significant German enterprises and employers include Meyer Werft, Bayer, and Lidl. The German-Finnish Chamber of Commerce (DFHK) based in Helsinki is the largest bilateral chamber of commerce operating in Finland.[26]

Resident diplomatic missions

[edit]Finland also has a consulate general in Hamburg, two honorary consulates general in Düsseldorf and Munich.

-

Embassy of Finland in Berlin

-

Embassy of Germany in Helsinki

See also

[edit]- Foreign relations of Finland

- Foreign relations of Germany

- Germans in Finland

- Kingdom of Finland (1918)

References

[edit]- ^ "Germany backs Sweden and Finland's potential NATO membership bids". euractiv.com. 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ HS, Jarmo Huhtanen (2018-09-09). "Maan uumenista on Suomessa paljastunut viime vuosina valtavasti tuhatvuotisia viikinkimiekkoja – Löydöt hämmästyttävät jopa arkeologian tohtoria". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Aminoff, Jukka (2021). Suomen Ruotsi ja Venäjä: Suomi muuttuvien maailmanjärjestysten keskellä. Helsinki: Readme.fi. ISBN 978-952-373-254-4.

- ^ a b c d "VirtuaaliViipuri - Saksalainen vaikutus Wiipurissa". virtuaaliviipuri.fi. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Airo, Paavo (2024-10-18). "Hakkapeliitat sotivat suomalaisille mainetta 400 vuotta sitten". Reserviläinen (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Bojesen, -Bjørn Arnfred; Julkaistu, Andreas Abildgaard | (2023-02-01). "Suomalainen ratsuväki pelasti päivän ja nosti Ruotsin suurvallaksi". historianet.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "K1, J3: Snellman Saksassa | Henkinen Eurooppamme | Yle Areena". areena.yle.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "tietokulma | Snellman palasi Saksaan". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 2006-11-14. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Wickberg, Nils Erik (1973). Carl Ludvig Engel. Helsinki.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Klinge, Matti (2020). Eurooppalainen Helsinki. Kirjokansi. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-951-858-185-0.

- ^ "Nationalismi muuttuu kansalliskiihkoksi – HiMa". www.hi3.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "FMQ - Universal, national or Germanised?". www.fmq.fi. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "Saksankielinen Helsinki". Suomi-Saksa Yhdistysten Liitto ry (in Finnish). 2025-09-26. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Kuisma, Markku; Finnilä, Anna; Keskisarja, Teemu; Sarantola-Weiss, Minna, eds. (2012). Hulluja päiviä, huikeita vuosia: Stockmann 1862-2012. Helsinki: Siltala. ISBN 978-952-234-086-3.

- ^ "Helsinki ensimmäisessä maailmansodassa". Yle Luovat sisällöt ja media (in Finnish). 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ John Horne, ed. (2011). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley & Sons. p. 561. ISBN 9781118275801.

- ^ "Apr 13, 1918: Germans capture Helsinki, Finland". History.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Saarinen, Hannes. "Friedrich Karl (1868 - 1940)". kansallisbiografia.fi. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "Suomen sata vuotta viennin vetämänä". Kauppapolitiikka (in Finnish). 2017-11-30. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Teija, Sutinen (1990-04-23). "Suomen metsäteollisuus kiinnosti ulkomaalaisia jo 1920-luvulla Saksa havitteli raakapuuta ja valtaa kansainvälisissä kartelleissa". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ Leatherman, Janie (2003). From Cold War to Democratic Peace: Third Parties, Peaceful Change, and the OSCE. Syracuse University Press. pp. 97–102. ISBN 9780815630326.

- ^ "Suomi ja Länsi-Euroopan taloudellinen integraatio". Elävä arkisto (in Finnish). 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "Tilastokeskus - Miten Suomi nousi köyhyydestä?". stat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "Yli sata vuotta globalisaation aalloilla – Suomen ulkomaankauppa ja kauppapolitiikka 1800-luvun lopulta nykypäivään". Työn ja talouden tutkimus LABORE (in Finnish). 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2025-10-16.

- ^ "Germany ratifies NATO membership for Finland, Sweden". www.reuters.com. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ a b c "Kahdenväliset suhteet". Suomi ulkomailla: Saksa (in Finnish). Retrieved 2025-10-16.

Further reading

[edit]- Cohen, William B., and Jörgen Svensson. "Finland and the Holocaust." Holocaust and Genocide Studies 9.1 (1995): 70-93.

- Hentilä, Seppo. "Maintaining neutrality between the two German states: Finland and divided Germany until 1973." Contemporary European History 15.4 (2006): 473-493.

- Holmila, Antero. "Finland and the Holocaust: A reassessment." Holocaust and Genocide Studies 23.3 (2009): 413-440. online[dead link]

- Holmila, Antero, and Oula Silvennoinen. "The Holocaust Historiography in Finland." Scandinavian Journal of History 36.5 (2011): 605-619. online[dead link]

- Lunde, Henrik O. Finland's War of Choice: The Troubled German-Finnish Coalition in World War II (Casemate, 2011).

- Rusi, Alpo. "Finnish-German Relations and the Helsinki-Berlin-Moscow Geopolitical Triangle." in The Germans and Their Neighbors (Routledge, 2019) pp. 179-198.

- Tarkka, Jukka. Neither Stalin nor Hitler : Finland during the Second World War (1991) online

- Vehviläinen, Olli. Finland in the second world war: between Germany and Russia (Springer, 2002).