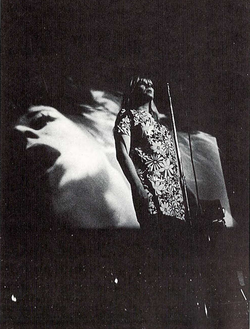

Exploding Plastic Inevitable

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable (originally known as the Erupting Plastic Inevitable[1] and later known as Plastic Inevitable or EPI), was a series of multimedia gesamtkunstwerk events organized by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey in 1966 and 1967, featuring musical performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico, screenings of Warhol's films, such as Eat, and dancing and mime performance art by regulars of Warhol's Factory, especially Mary Woronov and Gerard Malanga. The events were inspired by New York artist Bobb Goldsteinn, who had coined the term "multimedia" to describe his 1965 "lightworks".

In December 1966, Warhol included a one-off magazine called The Plastic Exploding Inevitable as part of the Aspen No. 3 package.[2]

Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable is also the title of an 18-minute film by Ronald Nameth with recordings from one week of performances of the shows which were filmed at Poor Richard's nightclub in Chicago, Illinois, in 1966.

Background

[edit]In 1963, Warhol was part of an avant-garde band called the Druds along with Patty Mucha, Lucas Samaras, Jasper Johns, Walter De Maria, La Monte Young, and Larry Poons. This project, albeit short-lived, demonstrates Warhol’s early engagement with performing music. By 1965, artist Bobb Goldsteinn began hosting Christmas parties for his friends which he called "Bob Goldstein’s Lightworks". In his Greenwich Village studio, Goldsteinn used manually synchronized light effects, slides, films, moving screens, and curtains of light under mirror balls to surround the spectator and simulate the effects of a visual jukebox.[3][4] Life magazine referred to the parties as "the seedbed of new sound and light concept,"[5] Women's Wear Daily proclaimed that "Lightworks' may well replace the discotheque, movies, TV, and everything else!",[6] and the New York Herald Tribune explained that "Bob Goldstein has managed to put into workable form something that lots of people have been reaching for... The problem for a long time has been to appeal to more than one of the senses at the same time".[7] The presentation became a continual happening, held both in New York City and in Southampton, Long Island at L’Oursin.[8][9]

By 1966, these performances by Goldsteinn led to him coining the term "multimedia", and also acted as an inspiration for Andy Warhol to create similar multimedia lightshows, first of which he held at the Electric Circus, an old venue which Warhol alongside Paul Morrissey, rented, redecorated and turned into a nightclub. Subsequently, Warhol began scouting for experimental rock bands to represent the music for what would later become the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, New York bands such as the Fugs and the Holy Modal Rounders were briefly considered by Warhol,[10] but in the end he ultimately chose the Velvet Underground, who were first introduced to him by Barbara Rubin, through Gerard Malanga, at the beatnik venue Café Bizarre in December 1965.[11][note 1] Warhol used Goldsteinn's name for the events, referring to them as "The Lightworks", though Goldsteinn quickly sent a cease and desist letter to Warhol, and the event's name was promptly changed to "The Balloon Farm", and later the "Exploding Plastic Inevitable".[12][13][14]

History

[edit]

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable had its beginnings in an event staged on January 13, 1966, at a dinner in the Delmonico Hotel for the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry. This event, called Up-Tight, included performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico, along with Malanga and Edie Sedgwick as dancers[15] and Barbara Rubin as a performance artist.[16] This lineup would later be present at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable's tour between 1966-67.

The first public EPI Happening, conceived of as a total immersion into a multimedia environment where the audience becomes part of the performance, was a 1966 month-long (April) performance at a Polish dance hall at 23 St. Marks Place in New York City called Polski Dom Narodowy (rechristened The Dom). That space would later become the Electric Circus. The Exploding Plastic Inevitable was advertised in The Village Voice as follows: "The Silver Dream Factory Presents The Exploding Plastic Inevitable with Andy Warhol/The Velvet Underground/and Nico."[17] For it, Warhol and Paul Morrissey rented The Dom[18] from the two light artists, Rudy Stern and Jackie Cassen,[19] and had it painted white so that movies and slide projections could be cast on the walls in wallpaper-like fashion. Five movie projectors were utilized along with five carousel-type slide projectors which could each change an image every ten seconds. Slides were projected directly onto the films, whose sound tracks would sometimes be played, and thus blend in with the lengthy live atonal Velvet Underground improvisations and their dark, provocative songs like "All Tomorrow's Parties", "Heroin" and "Venus in Furs".[13] A mirror ball also was utilized along with spot lights and strobe lights.[20]

E.P.I. shows, a barrage of flashing lights, multi-screened films, sadomasochistic mime, and noise music amplified into distortion, were later held in The Gymnasium in New York City and in various cities throughout Canada and the United States; including Chicago, Boston, Ann Arbor, Columbus, Ohio, Leicester, Massachusetts, Cleveland, Provincetown, Massachusetts, Los Angeles, and San Francisco where when asked to explain the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Warhol simply said that it's a totality.[13]

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable performed for the last time in May 1967, at Steve Paul's The Scene club in New York.[13]

Legacy

[edit]Additionally, Warhol's lights engineer Danny Williams pioneered many innovations that later became standard practice in psychedelic liquid light shows and subsequently rave culture.[21]

In 1966, from May 27–29 the EPI played the Fillmore in San Francisco, where Williams built a light show including stroboscopes, slides and film projections onstage.[22] At Bill Graham's request he was soon to come back and build more.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Gerard Malanga, the Bockris book's account of the introduction gets a few details wrong in regard to who was present in the Café Bizarre on which night. Also, according to Rosebud Pettet, Rubin made the introduction at Pettet's urging. All the sources seem to agree on one thing, however: It was Barbara Rubin who arranged the introduction.

References

[edit]- ^ Archives, The Voice (2018-09-26). "When the Voice Reviewed an Album for the Ages". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 22, 2025. Retrieved 2025-07-30.

- ^ "From the research laboratories of Andy Warhol comes this issue of Aspen Magazine". Evergreen Review. 11 (46). April 1967.

- ^ Eugenia Sheppard, "A Wham to the Senses," New York Herald Tribune, March 21, 1966

- ^ Thomas Meehan, "The Wiggy Scene," The Saturday Evening Post, October 22, 1966. Year 239. No. 22.

- ^ LIFE Magazine, May 27, 1966, Vol. 60, No. 21, p. 73

- ^ Ted James Jr., "Something New," Women's Wear Daily, January 21, 1966.

- ^ Eugenia Sheppard, "A Wham to the Senses," New York Herald Tribune, March 21, 1966.

- ^ Albert Goldman, Freakshow: Misadventures in the Counterculture, 1959-1971, New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001.

- ^ Leo Lerman, Mademoiselle, September 1966, Vol. 63, No. 5

- ^ "The Fugs". Bruno Ceriotti, rock historian. Retrieved 2025-06-25.

- ^ Bockris, Victor (1995). Transformer: The Lou Reed Story. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 102. ISBN 0-684-80366-6.

- ^ "Did You Know The Fillmore East's Joshua Light Show Really Started Here?". WestView News. 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2025-07-31.

- ^ a b c d [1] It Happened in 1966: Andy Warhol's Plastic Exploding Inevitable

- ^ Nevius, Michelle; Nevius, James (2009-03-24). Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. Simon and Schuster. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-4165-9393-5.

- ^ Joseph, Branden W. (Summer 2002). "'My Mind Split Open': Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable". Grey Room. 8: 80–107. doi:10.1162/15263810260201616. S2CID 57560227.

- ^ Blaetz, Robin, ed. (2007). Women's Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks. Duke University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780822340447.

- ^ Torgoff, Martin (2004). Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945–2000. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 156. ISBN 0-7432-3010-8. OCLC 54349574.

the silver dream factory.

- ^ [2] ingrid superstar gerard malanga paul morrissey and sterling morrison discuss EPI

- ^ Warhol, A. and Hackett, P. 1980. POPism: The Warhol' 60s. London: Hutchinson, p. 156

- ^ Warhol, A. and Hackett, P. 1980. POPism: The Warhol' 60s. London: Hutchinson, p. 156

- ^ "It Happened in 1966: Andy Warhol's Plastic Exploding Inevitable". msmokemusic.com. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ King, Homay (2014-11-25). "Moving On: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable". Retrieved 30 December 2019.