Draft:History of number theory

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about either yourself or your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Toukouyori Mimoto (talk | contribs) 20 days ago. (Update) |

originally forked from the history section in the number theory article

The history of number theory covers the development of the mathematical subfield. It focusses on number theory but also discusses related topics on arithmetic and numerology. One of the oldest branches of mathematics, number theory arose out of problems related to multiplications and division of integers.

From the ancient to post-classical periods, development was done independently around the world, starting in Babylon and Egypt. The ancient Greeks formalised number theory as a study. Their study included integer classes, divisibility, prime numbers, factorisation and Diophantine equations. Chinese mathematicians studied number theory for astronomy and the calendar, with their work culminating in the Chinese remainder theorem. In India, mathematicians innovated the use of zero and negative numbers and first studied Pell's equations. Development shifted to the Islamic world in the post-classical, expanding on Greek works.

Number theory witnessed a resurgence in Europe following the contributions of Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665), albeit it was again overshadowed by the development of calculus. He famously conjectured what would become Fermat's Last Theorem, and studied prime numbers. Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) authored over one thousand pages about number theory, frequently solving Fermat's assertions and extending ancient Greek works. Three European contemporaries continued the work in elementary number theory: Joseph-Louis Lagrange proved the four-square theorem and Wilson's theorem, Adrien-Marie Legendre proved specific cases of Fermat's Last Theorem, and Carl Friedrich Gauss introduced congruences.

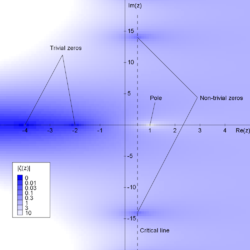

Euler's study of the zeta function formed a basis for the subfield of analytic number theory. Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet (1805-1859) pioneered the subfield's methods with a proof of his analytic theorem on arithmetic progressions. The subfield studies the distribution of primes and seeks for a function that approximates it. For example, would be proved by the end of the 19th century. Bernhard Riemann (1826-1866) found a connection between the zeta function and the prime-counting function, which he conjectured to be valid. By the 20th century, a plethora of subfields had had emerged, including algebraic, geometric, and combinatorial number theory. Algebraic number theory closed the millennium with the proof of Fermat's Last Theorem by Andrew Wiles.

Open questions remain, such as the Riemann hypothesis that is among the seven Millennium Prize Problems, Goldbach's conjecture on the representation of even numbers as the sum of two primes, and the existence of odd perfect numbers. Number theory was once regarded as the canonical example of pure mathematics with no applications outside the field. In 1970s, it became known that prime numbers would be used as the basis for the creation of public-key cryptography algorithms. Schemes such as RSA are based on the difficulty of factoring large composite numbers into their prime factors. Elementary number theory is taught in discrete mathematics courses for computer scientists.

Conception

[edit]

The history of number theory is the study of the historical development of the mathematical subfield. Number theory studies the structure and properties of integers as well as the relations and laws between them.[1] It arose out of problems related to multiplications and division of integers and is one of the oldest branches of mathematics alongside geometry. Its pre-modern period covers independent developments until the post-classical period. Modern number theory began in the 17th century. Influential subfields include elementary, analytic, algebraic, and geometric number theory.[2]

Number theory is closely related to arithmetic and some authors use the terms as synonyms.[3] In contemporary history, arithmetic is the study of numerical operations that extends to the real numbers. The ancient Greeks distinguished between "arithmētĭkḗ" and "logistikḗ". "Arithmētĭkḗ" is synonymous with the modern English "number theory", while "logistikḗ" is equivalent to "arithmetic", the practical use of numerical calculations. Number theory was reserved to scholars and royality.[4] In a more specific sense, number theory is restricted to the theoretical study of integers and focuses on their properties and relationships such as divisibility, factorization, and primality.[5] Traditionally, it is known as higher arithmetic.[6] The earliest appearance of the term number theory was in the 19th century.[7]

Another field that evolved alongside number theory is numerology. It treats numbers as objects of mystical properties. Pythagoreanism was a school of thought in ancient Greece that explored number theory on the premise of numerology. An influential type of numerology is gematria, which assigns numbers to alphabetical letters. The sum of letters in a word was said to reveal secrets, predict the future, and mark someone as evil. Numerology was not clearly distinguished from mathematics and is considered a pseudoscience in contemporary history.[8]

The earliest forms of arithmetic are sometimes traced back to counting and tally marks used to keep track of quantities. Some historians suggest that the Lebombo bone (dated about 43,000 years ago) and the Ishango bone (dated about 22,000 to 30,000 years ago) are the oldest arithmetic artifacts but this interpretation is disputed.[9] Some claim that tally marks on the Ishango bone list a sequence of prime numbers. Opponents argue that the concept of division, a precedent for prime numbers, evolved only after the rise of agriculture around 10,000 BC.[10] However, a basic sense of numbers may predate these findings and might even have existed before the development of language.[11]

Ancient to post-classical

[edit]A period of pre-modern developments in number theory is generally held to range from the dawn of civilisation to the 17th century. It covers fundamental concepts and theorems that rely on elementary proofs.[12] Development was done independently in cradles of civilisation in different around the globe. Early developments took place in Babylonia and Egypt. Influential developments include Greece, China, India, and the Islamic world.[13] Numerology motivated mathematicians from different cultures to study the nature of numbers.[14]

Early development

[edit]

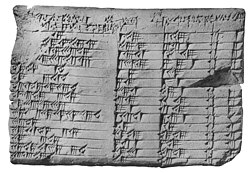

The development of number theory occurred independently and a systematic study did not exist. The knowledge of numbers existed in the early civilisations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and India. Surviving sources take the form of tablets, papyri, and carvings. The first positional numeral system was developed by the Babylonians starting around 1800 BCE. This was a significant improvement over earlier numeral systems since it made the representation of large numbers and calculations on them more efficient. They may have been familiar with prime factorisation.[15]

A famous Babylonian artefact of number theory is Plimpton 322. It is a fragment of a larger clay tablet, dated around 1800 BC, that contains a list of fifteen Pythagorean triples. A Pythagorean triple are three integers that satisfy the Pythagorean equation . Their study likely initiated with the observation of the triple (3, 4, 5). There is no academic consensus on the method of generation, purpose, and author. The triples are too large for the method to have been generated by brute force. Its purpose is theorised to be related to number theory, trigonometry, or astronomy. Some historians have considered it a teacher's catalogue of reciprocal pairs.[16]

Ancient Egyptian arithmetic took an additive approach to multiplication and division. They had a method of representing fractions as sums of distinct unit fractions. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, from around 1550 BC, has Egyptian fraction expansions of different forms for prime and composite numbers.[note 1] Around 300 BC, they knew a formula for the sum of triangular numbers.[note 2] Their awareness of Pythagorean triples is less certain. A problem in the Berlin Papyrus 6610 #1 involves finding integer terms that fulfil a Pythagorean equation, although the solution is a multiple of (3, 4, 5).[17]

Ancient Greece

[edit]While early civilizations primarily used numbers for concrete practical purposes like commercial activities and tax records, ancient Greek mathematicians began to explore the abstract nature of numbers. Their work survives in the form of book fragments and iterative copies.[18]

They formalised number theory as a field of study, establishing core concepts such as divisibility, factorisation, the greatest common divisor, and Diophantine equations.[19] A further contribution was their distinction of various classes of numbers, such as even numbers, odd numbers, and prime numbers.[20] This included the discovery that numbers for certain geometric lengths are irrational and therefore cannot be expressed as a fraction of integers.[21]

Most early Greeks did not consider 1 to be a number. They only considered and above to be numbers. A few scholars in the Greek and later Roman tradition, including Nicomachus, Iamblichus, Boethius, and Cassiodorus, also considered the prime numbers to be a subdivision of the odd numbers, so they did not consider to be prime either. However, Euclid and a majority of the other Greek mathematicians considered as prime.[22]

Archaic to classical

[edit]The works of philosophers Thales of Miletus and Pythagoras in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE are often regarded as the inception of Greek mathematics. Pythagoras founded the school of thought that sought to understand number theory, geometry, astronomy, and music. Plato later reaffirmed the four divisions of the mathematical sciences. Believing that everything revolves around numbers, the Pythagoreans tended to assign them mystical properties. For example, they considered to represent reason as it is foundational to all other numbers. Further mystics are Philo, Nicomachus, and Iamblichus.[23]

They visualised numbers as amounts of pebbles and studied polygonal numbers based on their arrangement. This included triangular, square, and pentagonal numbers. They also distinguished between classes such as odd and even, perfect, and amicable numbers. A perfect number is an integer that equals the sum of its proper divisors and was deemed virtuous. Similarly, they considered a pair of distinct integers to be friendly when the sum of the proper divisors of each is equal to the other integer, such as and .[24]

Hellenistic to early Roman

[edit]

Euclid (c. 300 BC) compiled in his Elements contemporary knowledge of geometry and number theory. He incorporated earlier Pythagorean studies of integer properties. In contrast to the Pythagorean mysticism, he used formal proofs to establish mathematical truths and validate theories, a novel feature in ancient Greek mathematics. He ordered his proofs in a logically deductive sequence, ultimately having all results be based on a set of self-evident axioms.[25]

The earliest surviving records of the study of prime numbers come from the ancient Greeks. Euclid established fundamental results concerning them, such as the infinitude of primes, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, and the relation between Mersenne primes and perfect numbers. To prove the infinitude, he showed the construction of a larger prime from any arbitrary prime. Euclid's lemma captures an important property of prime numbers and is key for the proof of the fundamental theorem. The fundamental theorem states that every integer greater than 1 is either prime or uniquely composed of a product of prime numbers.[note 3][26] He proved the construction of perfect numbers from prime numbers of the form .[note 4][27] Another contribution to prime numbers was made by Eratosthenes (3rd century BC). He devised a method to identify all primes up to a given bound. The Sieve of Eratosthenes is still used to construct lists of primes.[28]

Euclid gave the Euclidean algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor of two numbers. This involves repeatedly performing division with remainder and shifting numbers. The method works because the remainder is always less than the divisor. He presented a formula with two parameters to generate all Pythagorean triples and proved their infinitude. And if the greatest common divisor of the parameters is 1, then it generates primitive Pythagorean triples.[29]

Neopythagorean Nicomachus (2nd century) wrote the first systematic work that focuses solely on number theory entitled Introduction to Arithmetic. His work lacked rigour compared to the Elements and was possibly intended for a wider audience. Statements are typically illustrated with an example but not proved. It mostly discusses integer classes and includes the additional abundant and deficient numbers. In contrast to Euclid, who had a geometric image of numbers, Nicomachus represented numbers using letters with assigned values.[30]

Late antiquity

[edit]

Diophantus (3rd century) was an influential figure in later Greek arithmetic because of his contributions to number theory and the application of arithmetic operations to algebraic equations. In his Arithmetica, he examined polynomial equations with positive rational variables and experimented with symbolic notation. His work contains problems involving equations of up to 3rd polynomial degree. For example, the Pythagorean equation is a 2nd degree equation with the Pythagorean triples as its solutions. In modern terms, Diophantine analysis studies equations with integer variables, as opposed to positive rational ones.[31]

An epigram published by Lessing in 1773 appears to be a letter sent by Archimedes to Eratosthenes.[32] The epigram proposed what has become known as Archimedes's cattle problem; its solution (absent from the manuscript) requires solving an indeterminate quadratic equation (which reduces to what would later be misnamed Pell's equation). As far as it is known, such equations were first successfully treated by Indian mathematicians. It is not known whether Archimedes himself had a method of solution.

China

[edit]Chinese motivation for number theory was to solve problems in astronomy and calendar calculations. This included problems that would later be part of modular arithmetic. An anonymous 4th century tretise titled Sunzi Suanjing contains the first example of the Chinese remainder theorem. An exercise seeks for a number that returns the remainders 2, 3, 2 when divided by 3, 5, 7, respectively. The author gave 23 as the solution but there are infinitely many solutions.[33][34][note 5]

Althought often cited as the first appearance of the theorem, it is a concrete example and not a general theorem [CN]. The result was later generalized with a complete solution called Da-yan-shu (大衍術) in Qin Jiushao's 1247 Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections.[35] There is also some numerical mysticism in Chinese mathematics,[note 6] but, unlike that of the Pythagoreans, it seems to have led nowhere.

India

[edit]

While Greek astronomy probably influenced Indian learning, to the point of introducing trigonometry,[36] it seems to be the case that Indian mathematics is otherwise an autochthonous tradition;[37][38] in particular, there is no evidence that Euclid's Elements reached India before the eighteenth century.[39]

Ancient Indian traditions made inquiry into the nature of numbers. The Vedas contained preference for certain numbers and number classes. The Jains classified the numbers into the subsets of countable, uncountable and infinite numbers. Powers of 10 were assigned individual names. Buddhists and Jains listed terms for powers up to . The Vedic texts Śulbasūtras concerning the geometry of altar construction details the Pythagorean theorem and Pythagorean triples. Post-classical Indian mathematicians further studied the concepts of irrationality and the number zero. Varāhamihira (6th century) and Brahmagupta (7th century) examined the arithmetic under irrational numbers like the certain square roots. They observed and set rules for the arithmetic treatment of the number zero, which allowed the expansion of the domain of numbers and the development of algebra.[40]

Āryabhaṭa (476–550 AD) showed that the linear Diophantine equation could be solved by a method called kuṭṭaka (literally pulveriser), which searches for solutions by trial-and-error. The procedure is related to the Euclidean algorithm, which was probably discovered independently in India. Āryabhaṭa seems to have had in mind applications to astronomical calculations. Mahāvīra (9th century) refined it by eliminating trial-and-error. He also expressed interest in quadratic equations, number partitions, and fractions.[41]

Brahmagupta provided a general solution for the linear Diphantine equation. He also gave solutions to specific cases of Pell's equation.[note 7] Later authors would follow, using Brahmagupta's technical terminology. A general procedure (the chakravala, or "cyclic method") for solving Pell's equation was found by Jayadeva (11th century); the earliest surviving exposition appears in Bhāskara II's Bīja-gaṇita (12th century). Further contributions were made by Śrīpati, Narayana Pandita, and Madhava of Sangamagrama.[42]

RATIONALE OF THE CHAKRAVALA PROCESS OF JAYADEVA AND BHASKARA II

Islamic world

[edit]

In the early ninth century, the caliph al-Ma'mun ordered translations of many Greek mathematical works and at least one Sanskrit work (the Sindhind, which may[43] or may not[44] be Brahmagupta's Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta). Diophantus's main work, the Arithmetica, was translated into Arabic by Qusta ibn Luqa (820–912). Part of the treatise al-Fakhri (by al-Karajī, 953 – c. 1029) builds on it to some extent.[45] The medieval Islamic mathematicians largely followed the Greeks in viewing 1 as not being a number.[46]

Perfect and amicable numbers were also of interest the Arab-speaking world. This is in part due to the importance given to them by Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic.[47] Thabit ibn Qurra and Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi made notable discoveries. Thabit derived a method for generating amicable numbers and found more pairs. He also translated Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic into Arabic. Analogous to amicable numbers, Abu Mansur discovered a method to obtain balanced numbers. Two integers are called balanced if both sums of the respective proper divisors equal one another.[48]

Around 1000 AD, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) solved problems involving congruences using what is now called Wilson's theorem, characterizing the prime numbers as the numbers that evenly divide . In his Opuscula, Alhazen considers the solution of a system of congruences, and gives two general methods of solution. His first method, the canonical method, involved Wilson's theorem, while his second method involved a version of the Chinese remainder theorem. He also conjectured that all even perfect numbers come from Euclid's construction using Mersenne primes, but was unable to prove it.[49] Another Islamic mathematician, Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi, observed that the sieve of Eratosthenes can be sped up by considering only the prime divisors up to the square root of the upper limit.[50] in Diophantine analysis, Abu-Mahmud Khujandi stated a special case of Fermat's Last Theorem for n = 3, but his attempted proof of the theorem was incorrect.[51] Fibonacci took the innovations from Islamic mathematics to Europe. His book Liber Abaci (1202) was the first to describe trial division for testing primality, again using divisors only up to the square root.[52]

Other than a treatise on squares in arithmetic progression by Fibonacci—who traveled and studied in north Africa and Constantinople—no number theory to speak of was done in western Europe during the Middle Ages. Matters started to change in Europe in the late Renaissance, thanks to a renewed study of the works of Greek antiquity. A catalyst was the textual emendation and translation into Latin of Diophantus' Arithmetica.[53]

Early modern

[edit]Modern number theory began in the early modern period. The field saw a resurgence in Europe after a period of obscurity. Mathematicians expanded on prior works by the ancient Greeks. The field remained exclusive to elementary number theory, which used elementary methods like proof by infinite descent.[54]

17th century

[edit]

Pierre de Fermat (1607–1665) revitalised the study in Western Europe and is sometimes considered the founder of modern number theory. His work is contained in letters to mathematicians and in private marginal notes like in a copy of Diophantus's Arithmetica.[55] Although he drew inspiration from classical sources, he rarely wrote any proofs.[56]

One of Fermat's first interests was perfect numbers and amicable numbers. These topics led him to work on integer divisors, which were from the beginning among the subjects of the correspondence (1636 onwards) that put him in touch with the mathematical community of the day.[57] In 1638, Fermat claimed that all whole numbers can be expressed as the sum of four squares or fewer.[58] Fermat also investigated the primality of the Fermat numbers ,[59] and Marin Mersenne studied the Mersenne primes, prime numbers of the form with itself a prime.[60]

In the field of congruences, he described a fundamental result that would become Fermat's little theorem: if a is not divisible by a prime p, then . It was later proved by Leibniz and Euler.[61] Further, if a and b are coprime, then is not divisible by any prime congruent to −1 modulo 4;[62] and every prime congruent to 1 modulo 4 can be written in the form .[63] These two statements also date from 1640; in 1659, Fermat stated to Huygens that he had proven the latter statement by the method of infinite descent.[64]

In Diophantine analysis, Fermat proved by infinite descent that has no non-trivial solutions in the integers [NONPRIMARY SOURCE]. Fermat also mentioned to his correspondents that has no non-trivial solutions, and claimed that this could also be proven by infinite descent.[65][note 8][66] He generalised the statements, claiming to have proved that there are no solutions to for all . Fermat posed the problem of solving Pell's equation as a challenge to English mathematicians. The problem was solved in a few months by Wallis and Brouncker.[67] Fermat considered their solution valid, but pointed out they had provided an algorithm without a proof (as had Jayadeva and Bhaskara, though Fermat was not aware of this). He stated that a proof could be found by infinite descent.

18th century

[edit]

The interest of Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) in number theory was first spurred in 1729, when his correspondent Christian Goldbach pointed him towards some of Fermat's work on the subject.[68] This has been called the "rebirth" of modern number theory,[69] after Fermat's relative lack of success in getting his contemporaries' attention for the subject.[70] Euler's work on number theory includes the following:[71]

Euler proved many of Fermat's assertions and expanded upon ancient Greek works. This includes Fermat's little theorem (generalised by Euler to non-prime moduli); the fact that if and only if ; initial work towards a proof that every integer is the sum of four squares (the first complete proof is by Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1770), soon improved by Euler himself[72]); the lack of non-zero integer solutions to (implying the case n=4 of Fermat's last theorem, the case n=3 of which Euler also proved by a related method).

In a 1742 letter, Euler received Goldbach's conjecture that every even number is the sum of two primes.[73] Euler proved Alhazen's conjecture (now the Euclid–Euler theorem) that all even perfect numbers can be constructed from Mersenne primes.[74]

Pell's equation, first misnamed by Euler.[75] He wrote on the link between continued fractions and Pell's equation.[76] Quadratic forms. Following Fermat's lead, Euler did further research on the question of which primes can be expressed in the form , some of it prefiguring quadratic reciprocity.[77]

Diophantine equations. Euler worked on some Diophantine equations of genus 0 and 1.[78] In particular, he studied Diophantus's work; he tried to systematise it, but the time was not yet ripe for such an endeavour—algebraic geometry was still in its infancy.[79] He did notice there was a connection between Diophantine problems and elliptic integrals,[79] whose study he had himself initiated.

He introduced methods from mathematical analysis to this area in his proofs of the infinitude of the primes and the divergence of the sum of the reciprocals of the primes .[80] In his work of sums of four squares, partitions, pentagonal numbers, and the distribution of prime numbers, Euler pioneered the use of what can be seen as analysis (in particular, infinite series) in number theory. Since he lived before the development of complex analysis, most of his work is restricted to the formal manipulation of power series. He did, however, do some very notable (though not fully rigorous) early work on what would later be called the Riemann zeta function.[81]

19th century

[edit]

At the start of the 19th century, Legendre and Gauss conjectured that as tends to infinity, the number of primes up to is asymptotic to , where is the natural logarithm of . A weaker consequence of this high density of primes was Bertrand's postulate, that for every there is a prime between and , proved in 1852 by Pafnuty Chebyshev.[82]

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) was the first to give full proofs of some of Fermat's and Euler's work and observations; for instance, the four-square theorem and the basic theory of the misnamed "Pell's equation" (for which an algorithmic solution was found by Fermat and his contemporaries, and also by Jayadeva and Bhaskara II before them.) He also studied quadratic forms in full generality (as opposed to ), including defining their equivalence relation, showing how to put them in reduced form, etc.

Adrien-Marie Legendre (1752–1833) was the first to state the law of quadratic reciprocity. He also conjectured what amounts to the prime number theorem and Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions. He gave a full treatment of the equation [83] and worked on quadratic forms along the lines later developed fully by Gauss.[84] In his old age, he was the first to prove Fermat's Last Theorem for (completing work by Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet, and crediting both him and Sophie Germain).[85]

Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) worked in a wide variety of fields in both mathematics and physics including number theory, analysis, differential geometry, geodesy, magnetism, astronomy and optics. The Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (1801), which he wrote three years earlier when he was 21, had an immense influence in the area of number theory and set its agenda for much of the 19th century. Gauss proved in this work the law of quadratic reciprocity and developed the theory of quadratic forms (in particular, defining their composition). He also introduced some basic notation (congruences) and devoted a section to computational matters, including primality tests.[86] The last section of the Disquisitiones established a link between roots of unity and number theory:

The theory of the division of the circle...which is treated in sec. 7 does not belong by itself to arithmetic, but its principles can only be drawn from higher arithmetic.[87]

In this way, Gauss arguably made forays towards Évariste Galois's work and the area algebraic number theory.

Modern

[edit]

Starting early in the nineteenth century, the following developments gradually took place:

- The rise to self-consciousness of number theory (or higher arithmetic) as a field of study.[88]

- The development of much of modern mathematics necessary for basic modern number theory: complex analysis, group theory, Galois theory—accompanied by greater rigor in analysis and abstraction in algebra.

- The rough subdivision of number theory into its modern subfields—in particular, analytic and algebraic number theory.

Analytic

[edit]Ideas of Bernhard Riemann in his 1859 paper on the zeta-function sketched an outline for proving the conjecture of Legendre and Gauss. Although the closely related Riemann hypothesis remains unproven, Riemann's outline was completed in 1896 by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin, and the result is now known as the prime number theorem.[89] Another important 19th century result was Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions, that certain arithmetic progressions contain infinitely many primes.[90]

Many mathematicians have worked on primality tests for numbers larger than those where trial division is practicably applicable. Methods that are restricted to specific number forms include Pépin's test for Fermat numbers (1877),[91] Proth's theorem (c. 1878),[92] the Lucas–Lehmer primality test (originated 1856), and the generalized Lucas primality test.[93]

Pafnuty Chebyshev (1821-1894) provided substantiated cases for the PNT such as the existence of primes within specific intervals.

Dirichlet

Kummer

Dedekind

Riemann

Kronecker

Algebraic

[edit]Algebraic number theory may be said to start with the study of reciprocity and cyclotomy, but truly came into its own with the development of abstract algebra and early ideal theory and valuation theory; see below. A conventional starting point for analytic number theory is Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions (1837),[94] whose proof introduced L-functions and involved some asymptotic analysis and a limiting process on a real variable.[95] The first use of analytic ideas in number theory actually goes back to Euler (1730s),[96] who used formal power series and non-rigorous (or implicit) limiting arguments. The use of complex analysis in number theory comes later: the work of Bernhard Riemann (1859) on the zeta function is the canonical starting point;[97] Jacobi's four-square theorem (1839), which predates it, belongs to an initially different strand that has by now taken a leading role in analytic number theory (modular forms).[98]

Geometric

[edit]Others

[edit]Karam 2000 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKaram2000 (help)

Contemporary

[edit]

Since 1951 all the largest known primes have been found using these tests on computers.[a] The search for ever larger primes has generated interest outside mathematical circles, through the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search and other distributed computing projects.[100]

The American Mathematical Society awards the Cole Prize in Number Theory. Moreover, number theory is one of the three mathematical subdisciplines rewarded by the Fermat Prize.

The idea that prime numbers had few applications outside of pure mathematics[b] was shattered in the 1970s when public-key cryptography and the RSA cryptosystem were invented, using prime numbers as their basis.[103]

Number theory was once regarded as the canonical example of pure mathematics with no applications outside the field. In 1970s, it became known that prime numbers would be used as the basis for the creation of public-key cryptography algorithms. Schemes such as RSA are based on the difficulty of factoring large composite numbers into their prime factors. Elementary number theory is taught in discrete mathematics courses for computer scientists.

The increased practical importance of computerized primality testing and factorization led to the development of improved methods capable of handling large numbers of unrestricted form.[104] The mathematical theory of prime numbers also moved forward with the Green–Tao theorem (2004) that there are arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions of prime numbers, and Yitang Zhang's 2013 proof that there exist infinitely many prime gaps of bounded size.[105]

One quirk of number theory is that it deals with statements that are simple to understand but require a high degree of sophistication to solve. Open questions remain, such as the aforementioned Riemann hypothesis that is among the seven Millennium Prize Problems, Goldbach's conjecture on the representation of even numbers as the sum of two primes, and the existence of odd perfect numbers.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Related to Egyptian fractions, primary pseudoperfect numbers were first investigated in 2000.

- ^ The th triangular number is defined as . Ancient Egyptians discovered the formula .

- ^ The fundamental theorem of arithmetic was proved in modern terms by Gauss. It was then extended to abstract algebra, Gaussian integers, Eisenstein integers etc.

- ^ Open questions remain on the existence of odd perfect numbers and infinitude of Mersenne primes.

- ^ The date of the text has been narrowed down to 220–420 AD (Yan Dunjie) or 280–473 AD (Wang Ling) through internal evidence (= taxation systems assumed in the text). See Lam & Ang 2004, pp. 27–28.

- ^ See, for example, Sunzi Suanjing, Ch. 3, Problem 36, in Lam & Ang 2004, pp. 223–224

- ^ Pell's equation is a Diophantine equation of the form , where is a positive nonsquare integer.

- ^ The first known proof was provided by Euler (1753; indeed by infinite descent).

- ^ A 44-digit prime number found in 1951 by Aimé Ferrier with a mechanical calculator remains the largest prime not to have been found with the aid of electronic computers.[99]

- ^ For instance, Beiler writes that number theorist Ernst Kummer loved his ideal numbers, closely related to the primes, "because they had not soiled themselves with any practical applications",[101] and Katz writes that Edmund Landau, known for his work on the distribution of primes, "loathed practical applications of mathematics", and for this reason avoided subjects such as geometry that had already shown themselves to be useful.[102]

References

[edit]- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Boyer & Merzbach 1991, Platonic arithmetic and geometry

- Romanowski 2008, pp. 302–303

- HC staff 2022b

- MW staff 2023

- Bukhshtab & Pechaev 2020

- Page 2022, p. 16

- ^

- Wilson 2020, pp. 1–2

- Karatsuba 2020

- Campbell 2012, p. 33

- Robbins 2006, p. 1

- ^

- Duverney 2010, p. v

- Robbins 2006, p. 1

- ^

- ^

- Page 2022, pp. 16–17

- Ore 1948

- Tiwari 1992, p. 27

- ^

- Burgin 2022, pp. 2–3

- Ore 1948, pp. 1, 6, 8, 10

- Thiam & Rochon 2019, p. 164

- ^ Rudman 2007, pp. 62–65

- ^

- ^ Kleiner 2012, Early Roots to Fermat

- ^

- ^ Ore 1948

- ^

- ^

- Kleiner 2012, pp. 3–4

- Chahal 2025, pp. 71–72

- Rudman 2010, Pythagorean Triples

- Zhmud 2018, pp. 14–15

- ^

- Gillings 1974

- Corry 2015, p. 26

- Watkins 2014, p. 31

- Rudman 2010, Berlin Papyrus 6610 #1

- Burton 2011, Egyptian Arithmetic

- ^

- Burgin 2022, pp. 4–5, 15

- Brown 2010, p. 184

- Romanowski 2008, p. 303

- Nagel 2002, p. 178

- Burton 2011, pp. 83–84

- ^

- Burgin 2022, p. 15

- Madden & Aubrey 2017, p. xvii

- Burton 2011, 4.3 Euclid's Number Theory

- Dunham 2025

- ^

- Burgin 2022, p. 31

- Payne 2017, p. 202

- ^

- Burgin 2022, pp. 20–21

- Bloch 2011, p. 52

- ^

- Caldwell et al. 2012, pp. 3–4

- Tarán 1981

- ^

- Burgin 2022, p. 16

- Lützen 2023, p. 19

- Katz & Montelle 2024, pp. 38–39

- ^

- Burton 2011, p. 95

- Dunham 2025

- Burgin 2022, pp. 16–20

- ^

- Burgin 2022, p. 15

- Madden & Aubrey 2017, p. xvii

- Burton 2011, 4.3 Euclid's Number Theory

- Dunham 2025

- Kleiner 2012, p. 4

- ^ Burgin 2022, p. 66

- ^

- Stillwell 2010, p. 40

- Kleiner 2012, pp. 4–5

- ^

- ^

- Burton 2011, p. 177

- Kleiner 2012, pp. 4–5

- ^

- Burton 2011, Nicomachus's Introductio Arithmeticae

- Katz & Montelle 2024, pp. 50–51

- Goldman 1998, p. 2

- ^

- Burgin 2022, pp. 29–31

- Klein 2013a, p. 12

- Chahal 2025, Diophantus and Number Theory

- Kleiner 2012, p. 5

- Katz & Montelle 2024, pp. 82–83

- ^ Vardi 1998, pp. 305–319

- ^

- Kleiner 2012, p. 6

- Dunham 2025

- ^ Sunzi Suanjing, Chapter 3, Problem 26. This can be found in Lam & Ang 2004, pp. 219–220, which contains a full translation of the Suan Ching (based on Qian 1963). See also the discussion in Lam & Ang 2004, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Dauben 2007, p. 310

- ^ Plofker 2008, p. 119

- ^ Any early contact between Babylonian and Indian mathematics remains conjectural.

- ^ Plofker 2008, p. 42

- ^

- Plofker 2008, p. 119

- Mumford 2010, p. 387

- ^ Hayasi 2008, pp. 1763–1765

- ^

- Hayasi 2008, p. 1765

- Mumford 2010, p. 388

- Plofker 2008, p. 119

- ^

- Plofker 2008, p. 194

- Kleiner 2012, p. 6

- Hayasi 2008, p. 1765

- ^ Colebrooke 1817, p. lxv, cited in Hopkins 1990, p. 302. See also the preface in Sachau & Bīrūni 1888 cited in Smith 1958, pp. 168

- ^ Pingree 1968, pp. 97–125, and Pingree 1970, pp. 103–123, cited in Plofker 2008, p. 256.

- ^ Rashed 1980, pp. 305–321.

- ^ Caldwell et al. 2012, p. 6

- ^ van der Waerden 1961, Ch. IV

- ^ Berggen 2007, pp. 560–563

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- ^ Mollin 2002

- ^

- Razvi 1991, p. 358

- Bijli 2004, p. 44

- ^ Mollin 2002

- ^ Bachet, 1621, following a first attempt by Xylander, 1575

- ^

- Dunham 2025

- Goldman 1998, pp. 1, 86

- ^

- Apostol 1976, p. 5

- Weil 1984, pp. 45–46

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 118. This was more so in number theory than in other areas (Mahoney 1994, pp. 283–289). Bachet's own proofs were "ludicrously clumsy" (Weil 1984, p. 33).

- ^ Mahoney 1994, pp. 48, 53–54. The initial subjects of Fermat's correspondence included proper divisors and many subjects outside number theory; see the list in the letter from Fermat to Roberval, 22.IX.1636, Tannery & Henry 1891, Vol. II, pp. 72, 74, cited in Mahoney 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Faulkner, Nicholas; Hosch, William L. (2017). "Numbers and Measurements". Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-1-5383-0042-8. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ Sandifer, C. Edward (2014). How Euler Did Even More. Mathematical Association of America. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-88385-584-3.

- ^ Koshy, Thomas (2002). Elementary Number Theory with Applications. Academic Press. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-12-421171-1.

- ^ Sandifer 2007, p. 45

- ^ Tannery & Henry 1891, Vol. II, p. 204, cited in Weil 1984, p. 63. All of the following citations from Fermat's Varia Opera are taken from Weil 1984, Chap. II. The standard Tannery & Henry work includes a revision of Fermat's posthumous Varia Opera Mathematica originally prepared by his son Fermat 1679.

- ^ Tannery & Henry 1891, Vol. II, p. 213.

- ^ Tannery & Henry 1891, Vol. II, p. 423.

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 115

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 115–116

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 92.

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 2, 172.

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 2 and Varadarajan 2006, p. 37

- ^ Varadarajan 2006, p. 39 and Weil 1984, pp. 176–189

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Yuan, Wang (2002). Goldbach Conjecture. Series In Pure Mathematics. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). World Scientific. p. 21. ISBN 978-981-4487-52-8.

- ^ Stillwell 2010, p. 40

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 174. Euler was generous in giving credit to others (Varadarajan 2006, p. 14), not always correctly.

- ^ Weil 1984, p. 183.

- ^ Varadarajan 2006, pp. 44–47.

- ^ Varadarajan 2006, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Weil 1984, p. 181.

- ^ Narkiewicz 2000, p. 11

- ^ Varadarajan 2006, pp. 45–55; see also chapter III.

- ^ Tchebychev, P. (1852). "Mémoire sur les nombres premiers" (PDF). Journal de mathématiques pures et appliquées. Série 1 (in French): 366–390.. (Proof of the postulate: 371–382). Also see Mémoires de l'Académie Impériale des Sciences de St. Pétersbourg, vol. 7, pp. 15–33, 1854

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 332–334.

- ^ Weil 1984, pp. 337–338.

- ^ Goldstein & Schappacher 2007, p. 14.

- ^ From the preface of Disquisitiones Arithmeticae; the translation is taken from Goldstein & Schappacher 2007, p. 16

- ^ See the discussion in section 5 of Goldstein & Schappacher 2007. Early signs of self-consciousness are present already in letters by Fermat: thus his remarks on what number theory is, and how "Diophantus's work [...] does not really belong to [it]" (quoted in Weil 1984, p. 25).

- ^ Apostol 2000, pp. 1–14

- ^ Apostol 1976, 7. Dirichlet's Theorem on Primes in Arithmetical Progressions

- ^ Chabert 2012, p. 261

- ^ Rosen 2000, p. 342

- ^ Mollin 2002

- ^ Apostol 1976, p. 7.

- ^ See the proof in Davenport & Montgomery 2000, section 1

- ^ Iwaniec & Kowalski 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Granville 2008, pp. 322–348.

- ^ See the comment on the importance of modularity in Iwaniec & Kowalski 2004, p. 1

- ^ Cooper & Hodges 2016, pp. 37–38

- ^

- Ziegler 2004

- Rosen 2000, p. 245

- ^ Beiler 1999, p. 2

- ^ Katz 2004

- ^ Kraft, James S.; Washington, Lawrence C. (2014). Elementary Number Theory. Textbooks in mathematics. CRC Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4987-0269-0.

- ^

- Pomerance 1982

- Bauer 2013, p. 468

- Klee & Wagon 1991, p. 224

- ^ Neale 2017, pp. 18, 47.

Sources

[edit]- Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Introduction to analytic number theory. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90163-3. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1981). "An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Review of Hardy & Wright.)". Mathematical Reviews (MathSciNet). American Mathematical Society. MR 0568909. (Subscription needed)

- Apostol, Tom M. (2000). "A centennial history of the prime number theorem". In Bambah, R.P.; Dumir, V.C.; Hans-Gill, R.J. (eds.). Number Theory. Trends in Mathematics. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 1–14. MR 1764793.

- Aryabhata (1930). The Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa: An ancient Indian work on Mathematics and Astronomy. Translated by Clark, Walter Eugene. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Bauer, Craig P. (2013). Secret History: The Story of Cryptology. Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-6186-1.

- Becker, Oskar (1936). "Die Lehre von Geraden und Ungeraden im neunten Buch der euklidischen Elemente". Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik, Astronomie und Physik. Abteilung B:Studien (in German). 3: 533–553.

- Beiler, Albert H. (1999) [1966]. Recreations in the Theory of Numbers: The Queen of Mathematics Entertains. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-21096-4. OCLC 444171535.

- Berggen, Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". In Katz, Victor (ed.). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9. Retrieved 2025-09-02.

- Bijli, Shah Muhammad and Delli, Idarah-i Adabiyāt-i (2004) Early Muslims and their contribution to science: ninth to fourteenth century Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, Delhi, India, page 44, OCLC 66527483

- Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). The Real Numbers and Real Analysis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-72177-4.

- Boyer, Carl Benjamin; Merzbach, Uta C. (1991) [1968]. A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8. 1968 edition at archive.org

- Brezinski, Claude (1991). History of Continued Fractions and Padé Approximants. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-58169-4.

- Brown, David (2010). "The Measurement of Time and Distance in the Heavens Above Mesopotamia, with Brief Reference Made to Other Ancient Astral Science". In Morley, Iain; Renfrew, Colin (eds.). The Archaeology of Measurement: Comprehending Heaven, Earth and Time in Ancient Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11990-0.

- Bukhshtab, A.A.; Nechaev, V. I. (2014). "Elementary number theory". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Retrieved 2025-09-01.

- Bukhshtab, A. A.; Nechaev, V. I. (2016). "Natural Number". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Bukhshtab, A. A.; Pechaev, V. I. (2020). "Arithmetic". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Burgin, Mark (2022). Trilogy Of Numbers And Arithmetic - Book 1: History Of Numbers And Arithmetic: An Information Perspective. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-12-3685-3.

- Burton, David M. (2011). The History of Mathematics: An Introduction. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-338315-6.

- Caldwell, Chris K.; Reddick, Angela; Xiong, Yeng; Keller, Wilfrid (2012). "The history of the primality of one: a selection of sources". Journal of Integer Sequences. 15 (9): Article 12.9.8. MR 3005523. Archived from the original on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-01-15. For a selection of quotes from and about the ancient Greek positions on the status of 1 and 2, see in particular pp. 3–4. For the Islamic mathematicians, see p. 6.

- Campbell, Stephen R. (2012). "Understanding Elementary Number Theory in Relation to Arithmetic and Algebra". In Zazkis, Rina; Campbell, Stephen R. (eds.). Number Theory in Mathematics Education: Perspectives and Prospects. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-50143-2.

- Chabert, Jean-Luc (2012). A History of Algorithms: From the Pebble to the Microchip. Springer. p. 261. ISBN 978-3-642-18192-4.

- Chahal, J.S. (2025). Number Theory and Geometry through Histor. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-003-61354-1.

- Colebrooke, Henry Thomas (1817). Algebra, with Arithmetic and Mensuration, from the Sanscrit of Brahmegupta and Bháscara. London: J. Murray. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Cooper, S. Barry; Hodges, Andrew (2016). The Once and Future Turing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-107-01083-3.

- Corry, Leo (2015). A Brief History of Numbers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870259-7.

- Dauben, Joseph W. (2007), "Chapter 3: Chinese Mathematics", in Katz, Victor J. (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India and Islam : A Sourcebook, Princeton University Press, pp. 187–384, ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9

- Davenport, Harold; Montgomery, Hugh L. (2000). Multiplicative Number Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 74 (revised 3rd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95097-6.

- Davenport, H. (2008). The Higher Arithmetic: An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-45555-1.

- Dickson, Leonard Eugene (1952). History of the Theory of Numbers (8th ed.). Chelsea. ISBN 978-0-511-45555-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Dunham, William (12 March 2025). "Number theory". Britannica. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- Duverney, Daniel (2010). Number Theory: An Elementary Introduction Through Diophantine Problems. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4307-46-8.

- Edwards, Harold M. (November 1983). "Euler and Quadratic Reciprocity". Mathematics Magazine. 56 (5): 285–291. doi:10.2307/2690368. JSTOR 2690368.

- Edwards, Harold M. (2000) [1977]. Fermat's Last Theorem: a Genetic Introduction to Algebraic Number Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 50 (reprint of 1977 ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-95002-0.

- Effinger, Gove; Mullen, Gary L. (2022). Elementary Number Theory. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-003-19311-1.

- Fermat, Pierre de (1679). Varia Opera Mathematica (in French and Latin). Toulouse: Joannis Pech. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Frei, Günther (1994). "The Reciprocity Law from Euler to Eisenstein". In Chikara, Sasaki; Mitsuo, Sugiura; Dauben, Joseph W. (eds.). The Intersection of History and Mathematics. Birkhäuser. pp. 67–90. ISBN 978-3-0348-7521-9.

- Friberg, Jöran (August 1981). "Methods and Traditions of Babylonian Mathematics: Plimpton 322, Pythagorean Triples and the Babylonian Triangle Parameter Equations". Historia Mathematica. 8 (3): 277–318. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(81)90069-0.

- von Fritz, Kurt (2004). "The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum". In Christianidis, J. (ed.). Classics in the History of Greek Mathematics. Berlin: Kluwer (Springer). ISBN 978-1-4020-0081-2.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1966) [1801]. Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Translated by Waterhouse, William C. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-96254-2.

- Gillings, R.J. (1974). "The recto of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. How did the ancient Egyptian scribe prepare it?". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 12 (4): 291–298. doi:10.1007/BF01307175. MR 0497458. S2CID 121046003.

- Goldfeld, Dorian M. (2003). "Elementary Proof of the Prime Number Theorem: a Historical Perspective" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Goldman, Jay R. (1998). The Queen of Mathematics: A Historically Motivated Guide to Number Theory. Wellesley (Mass.): CRC Press. ISBN 1-56881-006-7.

- Goldstein, Catherine; Schappacher, Norbert (2007). "A book in search of a discipline". In Goldstein, C.; Schappacher, N.; Schwermer, Joachim (eds.). The Shaping of Arithmetic after C.F. Gauss's "Disquisitiones Arithmeticae". Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 3–66. ISBN 978-3-540-20441-1. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Granville, Andrew (2008). "Analytic number theory". In Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre (eds.). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11880-2. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Grigorieva, Ellina (2018). Methods of Solving Number Theory Problems. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-319-90915-8.

- Porphyry (1920). Life of Pythagoras. Translated by Guthrie, K. S. Alpine, New Jersey: Platonist Press. Archived from the original on 2020-02-29. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- Guthrie, Kenneth Sylvan (1987). The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Phanes Press. ISBN 978-0-933999-51-0.

- Hafstrom, John Edward (2013). Basic Concepts in Modern Mathematics. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-31627-7.

- Hardy, Godfrey Harold; Wright, E. M. (2008) [1938]. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921986-5. MR 2445243.

- Hayashi, Takao (2008). "Number Theory in India". In Seline, Helaine (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- HC staff (2022b). "Arithmetic". American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics, Volume 1: From Thales to Euclid. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Hindry, Marc (2011). Arithmetics. Universitext. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2131-2. ISBN 978-1-4471-2130-5.

- Hopkins, J. F. P. (1990). "Geographical and Navigational Literature". In Young, M. J. L.; Latham, J. D.; Serjeant, R. B. (eds.). Religion, Learning and Science in the 'Abbasid Period. The Cambridge history of Arabic literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32763-3.

- Huffman, Carl A. (8 August 2011). "Pythagoras". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Fall 2011 ed.). Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ITL Education Solutions Limited (2011). Introduction to Computer Science. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-6030-7.

- Iwaniec, Henryk; Kowalski, Emmanuel (2004). Analytic Number Theory. American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications. Vol. 53. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-3633-0.

- Plato (1871). Theaetetus. Translated by Jowett, Benjamin. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- Karam, P. Andrew (2000). "Advances in Number Theory between 1900 and 1949". In Schlager, Neil (ed.). Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Gale. pp. 252–254. ISBN 0-7876-3938-9.

- Karatsuba, A.A. (2020). "Number theory". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Retrieved 2025-05-03.

- Katz, Shaul (2004). "Berlin roots – Zionist incarnation: the ethos of pure mathematics and the beginnings of the Einstein Institute of Mathematics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem". Science in Context. 17 (1–2): 199–234. doi:10.1017/S0269889704000092. MR 2089305. S2CID 145575536.

- Katz, Victor J.; Montelle, Clemency, eds. (2024). Sourcebook in the Mathematics of Ancient Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691202815.

- Klee, Victor; Wagon, Stan (1991). Old and New Unsolved Problems in Plane Geometry and Number Theory. Dolciani mathematical expositions. Vol. 11. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-88385-315-3.

- Karam, P. Andrew (2000). "Advances in Number Theory between 1900 and 1949". In Schlager, Neil (ed.). Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Gale. pp. 252–254. ISBN 0-7876-3938-9.

- Kleiner, Israel (2000). "The Development of Number Theory during the Nineteenth Century". In Schlager, Neil (ed.). Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Gale Group. pp. 196–198. ISBN 0-7876-3937-0.

- Kleiner, Israel (2005). "Fermat: The Founder of Modern Number Theory". Mathematics Magazine. 78 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1080/0025570X.2005.11953295.

- Kleiner, Israel (2012). Excursions in the History of Mathematics. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-8268-2.

- Lam, Lay Yong; Ang, Tian Se (2004). Fleeting Footsteps: Tracing the Conception of Arithmetic and Algebra in Ancient China (revised ed.). Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-696-0. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Libbrecht, Ulrich (1973), Chinese Mathematics in the Thirteenth Century: the "Shu-shu Chiu-chang" of Ch'in Chiu-shao, Dover Publications Inc, ISBN 978-0-486-44619-6

- Long, Calvin T. (1972). Elementary Introduction to Number Theory (2nd ed.). Lexington, VA: D.C. Heath and Company. LCCN 77171950.

- Lozano-Robledo, Álvaro (2019). Number Theory and Geometry: An Introduction to Arithmetic Geometry. American Mathematical Soc. ISBN 978-1-4704-5016-8.

- Lützen, Jesper (2023). A History of Mathematical Impossibility. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286739-1.

- Madden, Daniel J.; Aubrey, Jason A. (2017). An Introduction to Proof Through Real Analysis. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-31472-1.

- Mahoney, M. S. (1994). The Mathematical Career of Pierre de Fermat, 1601–1665 (Reprint, 2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03666-3. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Mendell, Henry (2018). "Why Did the Greeks Develop Proportion Theory? A Conjecture". In Sialaros, Michalis (ed.). Revolutions and Continuity in Greek Mathematics. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-056365-8.

- Milne, J. S. (18 March 2017). "Algebraic Number Theory". Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Mollin, Richard A. (2002). "A brief history of factoring and primality testing B. C. (before computers)". Mathematics Magazine. 75 (1): 18–29. doi:10.2307/3219180. JSTOR 3219180. MR 2107288.

- Montgomery, Hugh L.; Vaughan, Robert C. (2007). Multiplicative Number Theory: I, Classical Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84903-6. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Moore, Patrick (2004). "Number theory". In Lerner, K. Lee; Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth (eds.). The Gale Encyclopedia of Science. Vol. 4 (3rd ed.). Gale. ISBN 0-7876-7559-8.

- Euclid; Proclus (1992). A Commentary on Book 1 of Euclid's Elements. Translated by Morrow, Glenn Raymond. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02090-7.

- Mueller, Ian (1981). Philosophy of mathematics and deductive structure in Euclid's Elements. Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13163-6. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- Mumford, David (March 2010). "Mathematics in India: reviewed by David Mumford" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 57 (3): 387. ISSN 1088-9477. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- MW staff (2023). "Definition of Arithmetic". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- MW Staff (10 September 2025). "Numberumber theory". www.merriam-webster.com.

- Nagel, Rob (2002). U-X-L Encyclopedia of Science. U-X-L. ISBN 978-0-7876-5440-5.

- Nagel, Ernest; Newman, James Roy (2008). Godel's Proof. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5837-3.

- Narkiewicz, Wladyslaw (2000). "1.2 Sum of Reciprocals of Primes". The Development of Prime Number Theory: From Euclid to Hardy and Littlewood. Springer Monographs in Mathematics. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-540-66289-1.

- Neugebauer, Otto E. (1969). The Exact Sciences in Antiquity. Vol. 9. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2.

- Neugebauer, Otto E.; Sachs, Abraham Joseph; Götze, Albrecht (1945). Mathematical Cuneiform Texts. American Oriental Series. Vol. 29. American Oriental Society etc.

- OED Staff (n.d.). "Number theory". oed.com.

- Ore, Øystein (1948). Number Theory and Its History. McGraw-Hill. Dover reprint, 1988, ISBN 978-0-486-65620-5.

- Page, Robert L. (2003). "Number Theory, Elementary". Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (Third ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-227410-7.

- O'Grady, Patricia (September 2004). "Thales of Miletus". The Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- Page, Robert L. (2002). "Number Theory, Elementary". In Meyers, Robert A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology: Num-Phos (3rd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 15–38. ISBN 0-12-227421-0.

- Payne, Andrew (2017). The Teleology of Action in Plato's Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879902-3.

- Pingree, David; Ya'qub, ibn Tariq (1968). "The Fragments of the Works of Ya'qub ibn Tariq". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 26.

- Pingree, D.; al-Fazari (1970). "The Fragments of the Works of al-Fazari". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 28.

- Plofker, Kim (2008). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- Pomerance, Carl (December 1982). "The Search for Prime Numbers". Scientific American. 247 (6): 136–147. Bibcode:1982SciAm.247f.136P. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1282-136. JSTOR 24966751.

- Ponticorvo, Michela; Schmbri, Massimiliano; Miglino, Orazio (2019). "How to Improve Spatial and Numerical Cognition with a Game-Based and Technology-Enhanced Learning Approach". In Vicente, José Manuel Ferrández; Álvarez-Sánchez, José Ramón; López, Félix de la Paz; Moreo, Javier Toledo; Adeli, Hojjat (eds.). Understanding the Brain Function and Emotions: 8th International Work-Conference on the Interplay Between Natural and Artificial Computation, IWINAC 2019, Almería, Spain, June 3–7, 2019, Proceedings, Part I. Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-19591-5.

- Qian, Baocong, ed. (1963). Suanjing shi shu (Ten Mathematical Classics) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. Archived from the original on 2013-11-02. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Rademacher, Hans (1942). "Trends in research: The analytic number theory". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 48 (6): 379–401. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- Rashed, Roshdi (1980). "Ibn al-Haytham et le théorème de Wilson". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 22 (4): 305–321. doi:10.1007/BF00717654. S2CID 120885025.

- Razvi, Syed Abbas Hasan (1991) A history of science, technology, and culture in Central Asia, Volume 1 University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan, page 358, OCLC 26317600

- Robbins, Neville (2006). Beginning Number Theory. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-0-7637-3768-9.

- Robson, Eleanor (2008). Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09182-2.

- Romanowski, Perry (2008). "Arithmetic". In Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth; Lerner, K. Lee (eds.). The Gale Encyclopedia of Science (4th ed.). Thompson Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-2877-2.

- Rose, H. E. (2002). "Number Theory, Algebraic and Analytic". In Meyers, Robert A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology: Num-Phos (3rd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 0-12-227421-0.

- Rosen, Kenneth H. (2000). "Theorem 9.20. Proth's Primality Test". Elementary Number Theory and Its Applications (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-201-87073-2.

- Rudman, Peter S. (2007). How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years. New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-477-4.

- Rudman, Peter S. (2010). The Babylonian Theorem: The Mathematical Journey to Pythagoras and Euclid. Amherst: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-773-7. Retrieved 2025-08-31.

- Sachau, Eduard; Bīrūni, ̄Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad (1888). Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy and Astrology of India, Vol. 1. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Sandifer, C. Edward (2007). How Euler Did It. MAA Spectrum. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-563-8.

- Serre, Jean-Pierre (1996) [1973]. A Course in Arithmetic. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 7. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90040-7.

- Smith, D. E. (1958). History of Mathematics, Vol I. New York: Dover.

- Stillwell, John (2010). Mathematics and Its History. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4419-6052-8.

- Stillwell, John (2019). A Concise History of Mathematics for Philosophers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-45623-4.

- Tannery, Paul; Fermat, Pierre de (1891). Charles Henry (ed.). Oeuvres de Fermat. (4 Vols.) (in French and Latin). Paris: Imprimerie Gauthier-Villars et Fils. Volume 1 Volume 2 Volume 3 Volume 4 (1912)

- Tanton, James (2005). "Number theory". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-5124-0.

- Tarán, Leonardo (1981). Speusippus of Athens: A Critical Study With a Collection of the Related Texts and Commentary. Philosophia Antiqua : A Series of Monographs on Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 39. Brill. pp. 35–38. ISBN 978-90-04-06505-5.</ref>

- Iamblichus (1818). Life of Pythagoras or, Pythagoric Life. Translated by Taylor, Thomas. London: J. M. Watkins. For other editions, see Iamblichus#List of editions and translations

- Thiam, Thierno; Rochon, Gilbert (2019). Sustainability, Emerging Technologies, and Pan-Africanism. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-22180-5.

- Tiwari, Sarju (1992). "A Mirror of Civilization". Mathematics in History, Culture, Philosophy, and Science (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-404-6. LCCN 92909575. OCLC 28115124. Retrieved November 13, 2025.

- Truesdell, C. A. (1984). "Leonard Euler, Supreme Geometer". Leonard Euler, Elements of Algebra. Translated by Hewlett, John (reprint of 1840 5th ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-96014-2. This Google books preview of Elements of algebra lacks Truesdell's intro, which is reprinted (slightly abridged) in the following book:

- Truesdell, C. A. (2007). "Leonard Euler, Supreme Geometer". In Dunham, William (ed.). The Genius of Euler: reflections on his life and work. Volume 2 of MAA tercentenary Euler celebration. New York: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-558-4. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Varadarajan, V. S. (2006). Euler Through Time: A New Look at Old Themes. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-3580-7. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Vardi, Ilan (April 1998). "Archimedes' Cattle Problem" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (4): 305–319. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.545. doi:10.2307/2589706. JSTOR 2589706. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- van der Waerden, Bartel L. (1961). Science Awakening. Vol. 1 or 2. Translated by Dresden, Arnold. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Watkins, John J. (2014). Number Theory: A Historical Approach. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15940-9.

- Weil, André (1984). Number Theory: an Approach Through History – from Hammurapi to Legendre. Boston: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-3141-3. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Weisstein, Eric W. (2003). CRC Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-347-2.

- Wilson, Robin (2020). Number Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879809-5.

- Yi, Ouyang (n.d.). Development of modern algebra and number theory since Galois and Kummer (PDF). Hefei: University of Science and Technology of China. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-12-05. Retrieved 2025-08-30.

- Zhmud, Leonid (2018). "Early Mathematics and Astronomy". In Keyser, Paul T.; Scarborough, John (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Science and Medicine in the Classical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199734146.

- Ziegler, Günter M. (2004). "The great prime number record races". Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 51 (4): 414–416. MR 2039814.

- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "History of number theory", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.