Draft:Convex polyhedron

| This is a draft article. It is a work in progress open to editing by anyone. Please ensure core content policies are met before publishing it as a live Wikipedia article. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL Last edited by Dedhert.Jr (talk | contribs) 11 hours ago. (Update)

Finished drafting? or |

| Definition | bounded intersections of finitely many half-spaces |

|---|---|

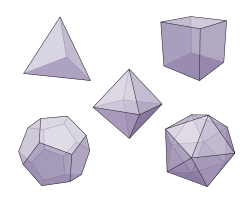

In geometry, a convex polyhedron (pl.: convex polyhedra) is a polyhedron whose interior is a convex set in the Euclidean space. It is a three-dimensional figure analogous to convex polygons in the Euclidean plane and convex polytopes in the Euclidean n-dimensional space. Many common families of polyhedra, such as cubes and pyramids, are convex. Famous types include Platonic solids and Archimedean solids.

Definition

[edit]Convex polyhedra are often defined as bounded intersections of finitely many half-spaces[1][2] or as the convex hull of finitely many points,[3] restricted in either case to intersections or hulls that have nonzero volume.

Types

[edit]

Notable types of convex polyhedra are the following:

- Prismatoids are the polyhedra whose vertices lie on two parallel planes and whose faces are likely to be trapezoids and triangles.[4] Examples of prismatoids are pyramids, wedges, parallelipipeds, prisms, antiprisms, cupolas, and frustums.

- Platonic solids are the five ancient polyhedra—tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, cube, and dodecahedron—described by Plato in the Timaeus.[5]

- Archimedean solids are the class of thirteen polyhedra whose faces are all regular polygons and whose vertices are symmetric to each other;[a] their dual polyhedra are the Catalan solids.[7]

- Johnson solids are the 92 convex polyhedra whose faces are all regular polygons.[8] These include the convex deltahedra, strictly convex polyhedra whose faces are all equilateral triangles.[9]

Less common types include:

- Symmetrohedron is the family of infinitely many highly symmetric convex polyhedra, coined by Craig S. Kaplan and George W. Hart, containing regular polygonal faces on symmetry axes with gaps on the convex hull filled by irregular polygons. This involves three-dimensional symmetric groups of tetrahedral, octahedral, and icosahedral symmetry.[10]

- Near-miss Johnson solid is a strictly convex polyhedron whose faces are close to being regular polygons, but some or all of which are not precisely regular. Thus, it fails to meet the definition of a Johnson solid, a polyhedron whose faces are all regular, though it "can often be physically constructed without noticing the discrepancy" between its regular and irregular faces.[10]

- Goldberg polyhedron is a convex polyhedron with hexagonal and pentagonal faces. Described by Goldberg (1937), it is obtained from regular octahedron, regular tetrahedron, and regular icosahedron.[11][12]

- A zonohedron is a convex polyhedron in which every face is a polygon that is symmetric under rotations through 180°.

General categories include:

- Convex polyhedra can be categorized into elementary polyhedra or composite polyhedra. Elementary polyhedra are convex, regular-faced polyhedra that cannot be produced into two or more polyhedra by slicing them with a plane.[13] Quite opposite to composite polyhedra, they can be alternatively defined as polyhedra constructed by attaching more elementary polyhedra. For example, triaugmented triangular prism is composite since it can be constructed by attaching three equilateral square pyramids onto the square faces of a triangular prism; the square pyramids and the triangular prism are elementaries.[14]

- Lattice polyhedra (or integral polyhedra) are convex polyhedra in which all vertices have integer coordinates.

Characterizations

[edit]The Euler characteristic stated that for any convex polyhedron, the calculation of its vertices, edges, and faces is always equal to 2; that is, .[15] A theorem by Alexandrov stated that every convex polyhedron is uniquely determined by the metric space of geodesic distances on its surface.

Midsphere and duality

[edit]

Some convex polyhedra possess a midsphere, a sphere tangent to each of their edges, which is intermediate in radius between the insphere and circumsphere for polyhedra in which all these spheres are present. Every convex polyhedron is combinatorially equivalent to a canonical polyhedron, a polyhedron that has a midsphere whose center coincides with the centroid of its tangent points with edges. The shape of the canonical polyhedron (but not its scale or position) is uniquely determined by the combinatorial structure of the given polyhedron.[16]

For every convex polyhedron , there exists a dual polyhedron having faces in place of the original's vertices and vice versa, and the same number of edges. The dual of a convex polyhedron can be obtained by the process of polar reciprocation. For a polyhedron that has a midsphere , the dual polyhedron also has the same midsphere . Hence, the face planes of the polar polyhedron pass through the circles on that are tangent to cones having the vertices of as their apexes, and the dual polyhedron's edges have the same points of tangency with the midsphere, at which they are perpendicular to the edges of .[17][18] Dual polyhedra exist in pairs, and the dual of a dual is just the original polyhedron again. Some polyhedra are self-dual, meaning that the dual of the polyhedron is congruent to the original polyhedron.[19]

Combinatorial structure

[edit]By forgetting the face structure, any polyhedron gives rise to a graph, called the skeleton of the polyhedron, with corresponding vertices and edges. Such figures have a long history: Leonardo da Vinci devised frame models of the regular solids, which he drew for Pacioli's book Divina Proportione, and similar wire-frame polyhedra appear in M.C. Escher's print Stars.[22] One highlight of this approach is Steinitz's theorem, which gives a purely graph-theoretic characterization of the skeletons of convex polyhedra: it states that the skeleton of every convex polyhedron is a planar graph with three-connected, and every such graph is the skeleton of some convex polyhedron. In other words, these are the connected graphs that can be drawn in the plane without any edges crossing, and that stay connected after removing any two of its vertices.[23]

A polyhedral graph is said to have Hamiltonian if there exists a cycle path passing through every vertex exactly once. A conjecture by Tait stated that every polyhedral cubic graph has a Hamiltonian cycle.[24] However, this conjecture was disproved by W. T. Tutte, giving a counterexample polyhedron with 25 faces, 69 edges, and 46 vertices.[25] Barnette later constrained the conjecture that remains unsolved nowadays, asking whether every bipartite cubic polyhedron is Hamiltonian or stating that every counterexample to Tait's conjecture is non-bipartite.[26]

Related theorems and problems

[edit]Many problems and open problems exist about convex polyhedra:[27][28][29]

- A shadow problem by Moser asks for estimating the function of a convex polyhedron's vertices. When a convex polyhedron with given vertices illuminated by parallel light rays at infinity, its shadow has at least the number of vertices, which is that function.[30]

- A Rupert property is a convex polyhedron where its copy of the same or similar size can pass through a hole in it.[31] It is conjectured that every convex polyhedron can have such a property, yet counterexampled by Steininger & Yurkevich (2021) with a Noperthedron—90 vertices, 240 edges, and 152 faces (150 triangles and 2 regular pentadecagons);.[32]

- inequalities for sums of edge lengths of polyhedra

- shadows of polyhedra

- dihedral angles of polyhedra

- rigidity of polyhedra

- counting polyhedra

- inscribable and circumscribable polyhedra

- lengths of paths on polyhedra

- polyhedra with congruent faces

- ordering the faces of a polyhedron

- the four color conjecture for toroidal polyhedra

Eberhard's theorem states about the sequences of polygonal faces in a three-dimensional simple convex polyhedron. Being simple means that every vertex of the polyhedron is incident to exactly three edges, hence incident to three angles of faces, and every edge is incident to two sides of faces.[33]

Non-convex polyhedron

[edit]Prominent non-convex polyhedra include the star polyhedra. The regular star polyhedra, also known as the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, are constructible via stellation or faceting of regular convex polyhedra. Stellation is the process of extending the faces (within their planes) so that they meet. Faceting is the process of removing parts of a polyhedron to create new faces (or facets) without creating any new vertices.[34][35] A facet of a polyhedron is any polygon whose corners are vertices of the polyhedron, and is not a face;[34] for example, a polygon involving diagonals (face diagonals or space diagonals). The stellation and faceting are inverse or reciprocal processes: the dual of some stellation is a faceting of the dual to the original polyhedron.[36] Other examples are the Chazelle polyhedron[37] and toroidal polyhedra.[38]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Archimedean solids once had a fourteenth solid known as the pseudorhombicuboctahedron, a mistaken construction of the rhombicuboctahedron. However, it was debarred for not having the vertex-transitive property, leading it to be instead classified as a Johnson solid.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2003), Convex Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 221 (2nd ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 26, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0019-9, ISBN 978-0-387-00424-2, MR 1976856

{{citation}}: Missing pipe in:|ref=(help). - ^ Bruns, Winfried; Gubeladze, Joseph (2009), "Definition 1.1", Polytopes, Rings, and K-theory, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Dordrecht: Springer, p. 5, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.2630, doi:10.1007/b105283, ISBN 978-0-387-76355-2, MR 2508056.

- ^ Buldygin, V. V.; Kharazishvili, A. B. (2000), Geometric Aspects of Probability Theory and Mathematical Statistics, Springer, p. 2, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-1687-1, ISBN 978-94-017-1687-1

- ^ Kern, William F.; Bland, James R. (1938), Solid Mensuration with proofs, p. 75.

- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. (1997), Polyhedra, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–52, ISBN 978-0-521-55432-9, MR 1458063.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2009), "An enduring error" (PDF), Elemente der Mathematik, 64 (3): 89–101, doi:10.4171/EM/120, MR 2520469. Reprinted in Pitici, Mircea, ed. (2011), The Best Writing on Mathematics 2010, Princeton University Press, pp. 18–31.

- ^ Diudea, M. V. (2018), Multi-shell Polyhedral Clusters, Carbon Materials: Chemistry and Physics, vol. 10, Springer, p. 39, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64123-2, ISBN 978-3-319-64123-2.

- ^ Berman, Martin (1971), "Regular-faced convex polyhedra", Journal of the Franklin Institute, 291 (5): 329–352, doi:10.1016/0016-0032(71)90071-8, MR 0290245.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn (1952), "Deltahedra", Mathematical Gazette, 36 (318): 263–266, doi:10.2307/3608204, JSTOR 3608204.

- ^ a b Kaplan, Craig S.; Hart, George W. (27–29 July 2001), "Symmetrohedra: Polyhedra from Symmetric Placement of Regular Polygons", in Sarhangi, Reza; Jablan, Slavik (eds.), Bridges: Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science, Winfield, Kansas, United States of America

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ Goldberg, Michael (1937), "A class of multi-symmetric polyhedra", Tohoku Mathematical Journal, 43: 104–108.

- ^ Schein, S.; Gayed, J. M. (2014), "Fourth class of convex equilateral polyhedron with polyhedral symmetry related to fullerenes and viruses", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (8): 2920–2925, Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.2920S, doi:10.1073/pnas.1310939111, ISSN 0027-8424, PMC 3939887, PMID 24516137.

- ^ Hartshorne, Robin (2000), "Example 44.2.3, the "punched-in icosahedron"", Geometry: Euclid and beyond, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, New York, p. 464, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-22676-7, ISBN 0-387-98650-2, MR 1761093.

- ^ Timofeenko, A. V. (2010), "Junction of Non-composite Polyhedra" (PDF), St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal, 21 (3): 483–512, doi:10.1090/S1061-0022-10-01105-2.

- ^ Richeson, D. S. (2008), Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology, Princeton University Press, pp. 1–2, ISBN 9780691126777.

- ^ Schramm, Oded (1992-12-01), "How to cage an egg", Inventiones Mathematicae, 107 (1): 543–560, Bibcode:1992InMat.107..543S, doi:10.1007/BF01231901, ISSN 1432-1297.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973), "2.1 Regular polyhedra; 2.2 Reciprocation", Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.), Dover, pp. 16–17, ISBN 0-486-61480-8, MR 0370327.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn; Rollett, A.P. (1961), "3.2 Duality", Mathematical models (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 78–79, MR 0124167.

- ^ Grünbaum, B.; Shephard, G.C. (1969), "Convex polytopes" (PDF), Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 1 (3): 257–300, doi:10.1112/blms/1.3.257, MR 0250188, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-22, retrieved 2017-02-21. See in particular the bottom of page 260.

- ^ Lawson-Perfect, Christian (13 October 2013), "An enneahedron for Herschel", The Aperiodical, retrieved 7 December 2016

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1948), Regular Polytopes, London: Methuen, p. 8

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1985), "A special book review: M.C. Escher: His life and complete graphic work", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 7 (1): 59–69, doi:10.1007/BF03023010, S2CID 189887063. Coxeter's analysis of Stars is on pp. 61–62.

- ^ Grünbaum (2003), pp. 235–244.

- ^ Tait, P. G. (1884), "Listing's Topologie", Philosophical Magazine, 5th Series, 17: 30–46. Reprinted in Scientific Papers, Vol. II, pp. 85–98.

- ^ Tutte, W. T. (1946), "On Hamiltonian circuits" (PDF), Journal of the London Mathematical Society, 21 (2): 98–101, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-21.2.98.

- ^ Barnette, David W. (1969), "Conjecture 5", in Tutte, W. T. (ed.), Recent Progress in Combinatorics: Proceedings of the Third Waterloo Conference on Combinatorics, May 1968, New York: Academic Press, MR 0250896.

- ^ Croft, Hallard T.; Falconer, Kenneth J.; Guy, Richard K. (1991). "Polygons, Polyhedra, and Polytopes". Unsolved Problems in Geometry. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Springer New York. p. 48–78. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0963-8_3. ISBN 978-1-4612-6962-5. Retrieved 2025-12-10.

- ^ Shephard, G. C. (1968). "Twenty Problems on Convex Polyhedra: Part I". The Mathematical Gazette. 52 (380). Mathematical Association: 136–147. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3612678. Retrieved 2025-11-22.

- ^ Shephard, G. C. (1968). "Twenty Problems on Convex Polyhedra Part II". The Mathematical Gazette. 52 (382). Mathematical Association: 359–367. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3611851. Retrieved 2025-11-22.

- ^ Lagarias, Jeffrey C.; Luo, Yusheng; Padrol, Arnau (2018), Moser's Shadow Problem, arXiv:1310.4345.

- ^ Jerrard, Richard P.; Wetzel, John E.; Yuan, Liping (April 2017), "Platonic passages", Mathematics Magazine, 90 (2), Mathematical Association of America: 87–98, doi:10.4169/math.mag.90.2.87, S2CID 218542147.

- ^ Steininger, Jakob; Yurkevich, Sergey (December 27, 2021), An algorithmic approach to Rupert's problem, arXiv:2112.13754.

- ^ Grünbaum (2003), pp. 253–271, 13.3 Eberhard's theorem.

- ^ a b Bridge, N.J. (1974), "Facetting the dodecahedron", Acta Crystallographica, A30 (4): 548–552, Bibcode:1974AcCrA..30..548B, doi:10.1107/S0567739474001306.

- ^ Inchbald, G. (2006), "Facetting diagrams", The Mathematical Gazette, 90 (518): 253–261, doi:10.1017/S0025557200179653, S2CID 233358800.

- ^ Malloy, Kaoime (2014), The Art of Theatrical Design: Elements of Visual Composition, Methods, and Practice, Taylor & Francis, p. 203, ISBN 978-1-317-69426-7.

- ^ Si, Hang; Goerigk, Nadja (2016), "On Tetrahedralisations of Reduced Chazelle Polyhedra with Interior Steiner Points", Procedia Engineering, 163: 33–45, doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.11.013

- ^ Croft, Hallard; Falconer, Kenneth; Guy, Richard (1991), Unsolved Problems in Geometry: Unsolved Problems in Intuitive Mathematics, p. 76, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0963-8, ISBN 978-1-4612-0963-8