Draft:Causes of the Third Crusade

| This is a draft article. It is a work in progress open to editing by anyone. Please ensure core content policies are met before publishing it as a live Wikipedia article. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL Last edited by AirshipJungleman29 (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update)

Finished drafting? |

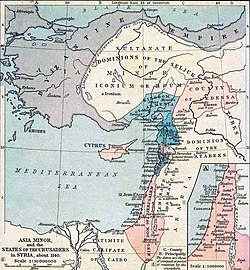

The prelude to the Third Crusade spans the period between the end of the Second Crusade in 1148 and the beginning of the Third Crusade in 1189.

The Second Crusade had concluded unsatisfactorily for the crusaders, who not only failed to achieve any concrete results but also had to witness, almost helplessly, the gradual Muslim unification of Syria accomplished by the atābeg (governor) of Aleppo, Nur al-Din, after 1150. Between 1163 and 1174, a new phase unfolded during which the Franks focused on Egypt, which was experiencing a difficult political situation. Ultimately, the Zengid Muslims prevailed, and Nur al-Din appointed a young subordinate named Saladin to lead Egypt, with whom he soon clashed due to Saladin’s ambitions for power. Upon Nur al-Din’s death, Saladin was able to unify both Syria and Egypt under his control, creating a solid Muslim state.

The crusaders faced a critical political situation after 1180, as they gradually lost ground, except for a few victories with limited impact. The dynastic crisis triggered by the death of the King Baldwin IV and the defeat at Hattin in 1187 paved the way for the Muslim reconquest of Jerusalem and many Christian settlements, a circumstance that prompted Pope Urban III and his immediate successor, Pope Gregory VIII, to proclaim a new crusade aimed at recapturing the holy city. This expedition saw the participation of the three main European sovereigns of the time, namely Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire, Philip II of France, and Richard I of England, but Jerusalem was never retaken by the crusaders.

Second Crusade

[edit]

The fall of Edessa, an important city held by the crusaders from 1098 to 1144, deeply shook Europe, which until then had observed the events unfolding in the Near East during the first half of the 12th century with relative passivity.[1] The possession of Edessa was also considered crucial for maintaining control of Jerusalem, located further south and in crusader hands for several decades.[1] The aggressive and astute policy adopted by the atābeg Zengi, the founder of the Zengid dynasty, had enabled the unification of the regions of Aleppo and Mosul under a single domain.[2] Crusader expansion was halted, with the County of Tripoli suffering the most significant damage from Muslim attacks.[2] Zengi’s immediate successor was his son Nur al-Din (Nūr ad-Din), who established himself in Aleppo and immediately focused on continuing the holy war against the Christians of Outremer.[3]

It was on these premises and the intense preaching activity of several church figures, most notably Bernard of Clairvaux, that Pope Eugene III proclaimed the Second Crusade.[4] Despite the involvement of the two most powerful European sovereigns of the first half of the 12th century, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, a series of issues compromised the expedition's outcome.[5][6] These included the lack of cohesion between Germans and French, the journey to the destination, during which a large number of soldiers died (most notably in the defeat at Dorylaeum on October 25, 1147),[7] and the decision to attack Damascus, the only city that intended to maintain peaceful relations with the crusaders due to its fear of Nur al-Din’s expansionist tendencies in Syria.[8] At the end of a brief five-day siege, the largest Frankish[note 1] army ever to arrive in the Near East withdrew from Damascus without achieving any concrete results.[9]

Unification of Syria

[edit]

The defeat suffered by the crusaders and the ongoing disputes in the Christian world allowed Nur al-Din to gradually complete the unification of all of Syria and significantly reduce the size of the Crusader states.[10] By enlisting many Turkmens and Kurds,[11] the atābeg soon achieved significant successes, such as the victory at the Inab in 1149, during which the Prince of Antioch, Raymond of Poitiers, lost his life.[6] This success enabled Nur al-Din to complete the conquest of the Orontes Valley.[6]

Despite some minor setbacks, Nur al-Din then caused the dissolution of the County of Edessa (July 1151), secured the wealthy city of Damascus without fighting its resisting Muslim lord (April 1154), and was responsible for the near-total destruction of the Principality of Antioch.[11][12] Meanwhile, the only significant conquest achieved by the crusaders, particularly by the King of Jerusalem Baldwin III, was the capture of Ascalon in 1153, an important port located just north of the modern Gaza Strip.[13]

Raids occurred intermittently in 1156 and were interrupted by a devastating earthquake that struck Syria, keeping both sides occupied with reconstruction for several months.[14] Peace was broken in February 1157, but although Nur al-Din’s attacks on Baniyas were unsuccessful,[15] the size of his domains eventually matched that of all the Frankish states combined.[16] When Nur al-Din fell seriously ill in October 1157, the crusaders attempted to capitalize on this through several raids.[17] The situation stabilized for some time along the Syro-Palestinian front when, in July 1158, the atābeg was defeated in the Battle of Butaiha.[18]

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos decided to travel to the eastern borders of his domains, an event that inspired optimism among the crusaders, who hoped it would secure them military support, and frustration among the Muslims, who feared the potential of that army.[19] Of his own accord, Nur al-Din immediately requested a pact of cooperation with Manuel in an anti-Seljuk context, offering gifts and declaring his readiness to release numerous Christian prisoners.[20][21] The emperor accepted the proposal in May 1159, as the Seljuks posed a far greater threat to him than the atābeg due to their aggressiveness.[20][21] Upon receiving news of the agreement, the Franks were deeply dismayed, realizing that Manuel had acted solely to strengthen the geopolitical weight of his empire, not to commit to fighting alongside them.[20]

Moreover, the cooperation agreement between Manuel and Nur al-Din was concretely implemented between late 1159 and early 1160, forcing the Seljuk sultan Kilij Arslan II, recognizing his inferiority, to accept becoming a vassal of Nur al-Din.[21] In the same year, Majd al-Din, milk brother of Nur al-Din, captured the Prince of Antioch Reynald of Châtillon following a raid in the Anti-Taurus Mountains.[22][note 2] In Antioch, Reynald had gained notoriety for his dissolute behavior and greed for wealth.[23] For this reason, during the sixteen years he remained in captivity, neither Baldwin III nor the people of Antioch showed much haste or interest in securing his release.[24]

While Nur al-Din was in the north, Baldwin III conducted minor raids around Damascus.[22] Najm al-Din Ayyub, Nur al-Din’s lieutenant (and father of Saladin), negotiated a three-month truce, after which the Franks launched another invasion.[25] In the autumn of 1161, Nur al-Din returned and secured another truce with Baldwin. With Antioch under nominal Byzantine control and the southern Crusader states too weak to launch further attacks in Syria, the atābeg decided to undertake an hajj (a pilgrimage to Mecca).[25] Upon his return in the first half of 1162, he learned of Baldwin III’s death, but despite the opportunity for a surprise attack, he chose to respect the crusaders’ mourning and refrained from offensive actions.[25]

Eager to expand his domains, Nur al-Din had set his sights on Egypt, ruled by the Fatimid dynasty and torn by a difficult political situation.[26] The idea of advancing toward that region soon spread among the Franks, particularly on the initiative of the new king Amalric I of Jerusalem, who succeeded the deceased Baldwin.[27] Like others, he was aware that a united Muslim Syria now had little chance of being quickly conquered, which is why he turned to a new objective.[28] The first campaign, undertaken by Amalric in September 1163, was merely exploratory and was halted by floods caused by the Nile.[27][29] Nevertheless, Amalric realized there was potential to establish a permanent presence in Egypt.

Meanwhile, the local vizier Shawar, ousted by his rival Ḍirghâm, reached Syria and asked Nur al-Din to send him aid.[27] Taking advantage of Amalric’s absence, Nur al-Din attempted to attack the smallest and most fragile of the Crusader states, the County of Tripoli.[29] However, the attack on Krak des Chevaliers, the region’s main fortress, known as the Battle of al-Buqaia in September 1163, failed thanks to the intervention of a group of French nobles (including Hugh VIII of Lusignan) returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[30] Nur al-Din then sent an army to Egypt led by his loyal Kurdish lieutenant Shirkuh, who brought along his young nephew Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb (who would later be known as Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn, Latinized as Saladin), enabling the vizier Shawar to return to power.[31][32] However, feeling threatened by Shirkuh’s troops camped at the gates of Cairo, the vizier broke the agreement with Nur al-Din and sought Amalric’s help in 1164.[31][33]

In an attempt to divert the crusaders’ attention from Bilbeis, where Shirkuh was located, Nur al-Din attacked the Principality of Antioch, massacring many Christian soldiers and capturing numerous crusader leaders in the Battle of Harim.[33] Nur al-Din, however, chose not to advance directly against Antioch, fearing it would provoke the intervention of the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos.[31][34] Since Amalric understood that prolonging his absence would lead to further territorial losses, he proposed an agreement with Shirkuh, whereby both would leave Egypt and preserve the status quo.[33] The Kurdish general, short on supplies, agreed, leaving Egypt in Shawar’s hands in November 1164.[33]

In 1167, Nur al-Din sent Shirkuh again to conquer Egypt, once more accompanied by the young Saladin.[31][35] Once again, Shawar called on Amalric for help, and the King of Jerusalem attempted to strike the enemy multiple times.[31] The crusader and Egyptian forces managed to halt Shirkuh, though without defeating him decisively, forcing him to retreat toward Alexandria.[36] In the end, Shirkuh sent Saladin to negotiate; the young man proved to be a skilled diplomat, securing an agreement whereby the Muslims would leave Egypt by sea with a safe-conduct.[37] In October 1168, Amalric decided to break the alliance with Shawar and attack Egypt, enticed by the prospect of gaining spoils and relics but lacking additional reinforcements.[38] He thus laid siege to Bilbeis and massacred its population, which immediately developed a strong aversion to the crusaders, initially seen as “liberators from the anarchic misrule of the Fatimid caliphate.”[39] As a result, Shawar turned to his old enemy Nur al-Din to defend himself against Amalric’s betrayal.[40] Lacking sufficient forces to sustain a prolonged siege of Cairo, Amalric ultimately decided to withdraw.[40] Meanwhile, the new alliance allowed Nur al-Din to extend his control over the entire northern part of the so-called Fertile Crescent and, thanks to Shawar’s weakness, to place a heavy claim on Egypt.[40]

Rise of Saladin and the crisis

[edit]

Shawar was sentenced to death for his alliance with the crusaders, while Shirkuh succeeded him as vizier of Egypt.[40] However, in 1169, Shirkuh died after only a few weeks of rule due to severe indigestion.[39] His nephew Saladin succeeded him in the role, rising to power at thirty-one and relatively unknown to the Egyptian people.[41] There has been much debate about the reason for his appointment, but it is generally believed he was a compromise candidate, proposed by the Syrian emirs and appointed by the caliph.[42] Over time, Nur al-Din regretted his decision, as he began to fear Saladin’s ambitions, especially after the success of his campaigns in Yemen, Cyrenaica, and Nubia.[43][44] On the two occasions when the atābeg urged Saladin to assist in the siege of Krak des Chevaliers, the Egyptian ruler always found an excuse, and his absence prevented its conquest.[44]

Nur al-Din considered mounting an expedition against his subordinate but died in 1174, leaving his empire to his eleven-year-old son As-Salih Ismail al-Malik.[45] Saladin was given an opportunity to insert himself into the struggles that erupted in Syria by Ibn al-Muqaddam, minister of al-Ṣāliḥ Ismāʿīl.[46] Ibn al-Muqaddam welcomed Saladin to Damascus, and Saladin positioned himself as the young emir’s guardian, immediately focusing on reconquering the territories that had declared autonomy after Nur al-Din’s death.[46] Some of his main adversaries were the Zengids, lords of Damascus, Baalbek, and Homs.[47] Hostile to Saladin, they were defeated in the Battle of the Horns of Hama on April 13, 1175, and were forced to sign a treaty acknowledging Saladin’s supremacy over all of Syria, except for Aleppo.[47] The geopolitical landscape had undergone significant changes; “instead of a confused conglomeration of petty states, there now existed a powerful and united Syria, with Egypt under its sovereignty.”[48] Saladin did not achieve decisive victories in Aleppo even in 1176 and narrowly escaped two assassination attempts that summer by the Assassins, who targeted him when he attacked Masyaf, their main stronghold.[49] Moving to Egypt, he struck an agreement not to attack the Assassins,[50] and became convinced of the need to continue the jihad (holy war) against the crusaders.[48]

The King Amalric had died, like Nur al-Din, in 1174, leaving the throne of Jerusalem to his nearly thirteen-year-old son Baldwin IV, who was afflicted with leprosy.[51][52] The Frankish world was divided on the course of action to take, split between a faction favoring peace with the Muslims, believing the time was not ripe for battle, and a more uncompromising, hardline faction.[53] The latter group prevailed, leading to incessant military expeditions against Egypt from 1175 to 1178.[54] In particular, when Philip of Flanders arrived in 1177, Baldwin and the Byzantine delegates were convinced of the real possibility of a successful campaign.[54] These expectations were dashed when Philip refused to participate,[54] but Baldwin IV pressed forward nonetheless. As war flared up again, the Christian king achieved a significant victory on November 25, 1177, in the Battle of Montgisard, catching Saladin’s army by surprise as it marched toward Jerusalem and managing, with a significantly smaller force, to prevail; it is said that Saladin escaped capture only by chance.[55][56] The Muslim sovereign had a chance to redeem himself on June 10, 1179, when at Marjayoun, near Mount Lebanon, he decisively defeated Baldwin and his entourage.[57][58] He then secured another victory by attacking the Christian king’s castle at Jacob’s Ford between August 24 and 29.[59]

Although a truce had been sealed in 1181, the newly freed Prince of Antioch Reynald of Châtillon, renouncing the negotiations and constantly engaging in plundering, continued to attack caravans passing through the Beqaa Valley and, in particular, one of pilgrims heading to Mecca for the hajj.[60] The fragile crusader political situation allowed Reynald to extend his piratical activities to the Red Sea, with his galleys making navigation extremely dangerous for Muslims traveling to the Holy City of Islam.[61] The violence perpetrated against pilgrims sparked widespread hatred in the Muslim world toward Reynald.[61] Despite ordering him to cease his raids, Reynald disobeyed, prompting Saladin to attack him; Baldwin had the foresight to accept Reynald’s request for assistance and came to his aid.[61] Saladin launched an offensive in May 1182, and the two armies clashed in July at the Battle of Belvoir Castle, fought near the namesake castle.[62] Although the Franks resisted, the victory was not decisive and allowed Saladin to attack Beirut shortly afterward.[62] The stronghold, however, was robust and did not surrender, forcing the attackers to retreat.[63] In 1183, Saladin became convinced of the need to secure the strategic fortress of Kerak, held by Reynald of Châtillon.[64] At the end of November, he initiated the siege, but he abandoned it a few days later upon learning of the approach of Baldwin’s army.[65] The Christian king, increasingly weakened by the leprosy from which he suffered, died in 1185, and the throne passed to his nephew Baldwin V, then only a five-year-old child.[66] The regency of Jerusalem was thus held by Raymond III of Tripoli.[66]

The following year, Baldwin V died, and he was succeeded by Princess Sibylla (sister of Baldwin IV and mother of Baldwin V), who named her new husband Guy of Lusignan as king consort in September or October 1186.[67] The internal division within the crusader world was more evident than ever in this specific historical context.[68] One of the most tangible conflicts was between Guy of Lusignan and Raymond III of Tripoli, which arose following Baldwin V’s death: Raymond had refused to recognize Guy’s authority as king of Jerusalem.[69] It was only the barons who dissuaded Guy from sparking a war with Raymond, who in 1186 signed “a pact of security and guarantee” with Saladin.[69][70]

Paradoxically, it was Reynald of Châtillon, despised by both Guy and Raymond, who prompted the two rivals to set aside their differences.[71][72] Reynald had attacked another wealthy caravan during a time of peace, depriving its members of their freedom;[72][73] Saladin demanded that the prisoners be released and the cargo returned.[72][73] Guy also ordered Reynald to release the captives, but the king’s request went unheeded.[72][73] On March 13, 1189, Saladin, who was waiting for a pretext to break the peace and launch an offensive northward, declared war on the Franks and set out from Damascus.[74] The situation forced the crusaders to temporarily set aside their disputes, as it was said that the Kurdish sultan led “an enormous army, like an ocean.”[72] The defeat suffered by the Grand Master of the Templars, Gerard de Ridefort, at the Cresson, near Nazareth on May 1, 1187, exacerbated the problem.[75] It became clear that Saladin aimed for Jerusalem and that his interest in this goal was driven by strategic motives.[76] It was only at the last moment that Guy of Lusignan and a reluctant Raymond III of Tripoli reconciled, concentrating their combined forces at Sephorie, in the heart of Galilee, halfway between the city of Tiberias and the sea.[77] This mobilization allowed them to muster about 1,500 knights and 20,000 foot soldiers, in addition to local sentries.[77]

At the time of Saladin’s attack, Tiberias seemed destined to succumb to enemy pressure, so much so that within an hour, the lower city had already been lost by the crusaders.[78] The severity of the situation required the Franks who came to the rescue to find a solution quickly. The crusader army was in poor condition, exhausted by the scorching July heat and thirst, aware of its numerical inferiority, and demoralized by the ongoing conflicts among its commanders.[79] Raymond III was entirely skeptical of the decisions imposed by Guy, supported by both Prince Reynald of Châtillon and the Templar master Gerard de Ridefort.[80] Questionably, Guy had allowed Saladin time to encamp and secure the strategically superior position, namely the shores of Lake Tiberias.[80] In contrast, he had positioned himself on barren hills east and south of the lake.[80] On the evening of July 3, King Guy decided to march with his army to the Horns of Hattin, basaltic ridges not far from the city of Tiberias.[81] During the night, the crusader soldiers found themselves completely surrounded by Saladin, who had set fire to the surrounding dry grass, as the wind was blowing toward his enemies.[80] Under these conditions, the crusader armies were easily massacred in the Battle of Hattin, during which Saladin likely led the largest army he had ever commanded (approximately 30,000 men).[71] Raymond managed to escape the disaster by breaking through and fleeing to Tiberias, while the main culprits of the defeat—Guy of Lusignan, Reynald of Châtillon, and Gerard de Ridefort—were taken prisoner.[80] While treating the barons and the king courteously, the despised Reynald was harshly rebuked by Saladin and, when he responded in sharp tones, “the sultan beheaded him with his own hand.”[81][82] Saladin ordered that the Christians not be killed, and his order was respected.[82] Many of the prisoners reached Damascus, where they were sold as slaves; it is said that their price fell so low that one man reportedly bought a slave in exchange for a pair of sandals.[83] Guy was held first in Nablus and then in Latakia, but was released in 1188 due to the persistent pleas of his wife, Sibylla.[84] This was not an act of mercy: Saladin calculated that Guy’s release would cause discord in the Christian world, and his subsequent personal struggles to maintain the royal title proved the sultan’s calculation correct.[85]

The defeat at Hattin turned into “an unprecedented disaster.”[82] With the Frankish cavalry decimated and the bulk of the crusader army annihilated, Saladin first seized the important port city of Acre on July 10, then Beirut (August 6, 1187), and finally the other ports of Lebanon.[86] On September 5, after prolonged fighting, Ascalon fell.[86] When Saladin appeared before the gates of Jerusalem, he offered the crusaders the chance to surrender with their lives spared.[82] The defenders, however, refused to relinquish control of the city without a fight, leading to a battle.[82] After two weeks, resistance proved impossible to sustain, and on October 2, 1187, the occupants surrendered.[82][87] Violence against Christian prisoners was avoided on Saladin’s orders.[87] They were allowed to ransom themselves by paying a relatively low sum of money.[82] Since some poor individuals could not afford it, the sultan released many of them without demanding any ransom.[88]

Meanwhile, the crusaders who survived the defeat at Hattin had taken refuge in Tyre, the most fortified city along the coast.[89] The sultan hesitated, fearing that the city could withstand a prolonged siege.[89] This gave the occupants of Tyre, aided by the arrival of reinforcements led by Conrad of Montferrat, time to prepare adequately and repel the siege that took place between November 1187 and January 1188.[90] Despite this, the crusader situation appeared desperate, considering the heavy losses suffered and the fact that the few strongholds that escaped Saladin’s advance (Tyre, Tripoli, and Antioch) seemed on the verge of Islamic conquest.[91]

Preparations for the Third Crusade

[edit]

According to tradition, Pope Urban III died of stroke on October 20, 1187, upon hearing of these events, just managing to complete the writing of the encyclical Audita tremendi.[92] The new pontiff, Gregory VIII, declared that the fall of Jerusalem was to be considered God’s punishment for the sins of Christians in Europe.[92] It was thus decided to prepare for a new crusade: Henry II of England and Philip II of France ended the war that had pitted them against each other, and both imposed the so-called Saladin tithe, “a ten percent tax on income and movable goods” to finance the expedition.[93] The Archbishop of Canterbury, Baldwin of Exeter, alone, while traveling through Wales, managed with great fervor to convince numerous men to set out for the Holy Land (as recounted by Gerald of Wales in his Itinerario).[93] At Gisors, on January 22, 1188, King Philip Augustus of France and King Henry II of England temporarily resolved their differences and decided to embark on the crusade.[93][note 3]

Prominent participants in the Third Crusade included Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire, along with the aforementioned kings of France and England, and numerous other groups of European fighters who went to the Holy Land hoping to recapture Jerusalem.[94] For instance, the Pisans, led by their archbishop Ubaldo Lanfranchi, were joined in the late summer of 1189 by the Genoese and Venetians.[94] Over the summer, various French and Burgundians arrived, including, for example, Theobald V of Blois and his brother Stephen I of Sancerre.[95] On September 1, a large fleet carrying various Frisians and Danes (estimated, likely exaggeratedly, at around 500) landed,[96] of whom only about a hundred survived the crusade.[94] During their journey, they had conquered Alvor, taking it from the Moors on behalf of the Portugal.[94] A small fleet of London fighters also left the Thames in August and reached Portugal a month later. There, as had happened forty years earlier with other Englishmen, they agreed to serve temporarily the Portuguese king Sancho I.[96] With their help, he was able to wrest from the Almohads, after a siege, the castle of Silves, located east of Cape of St. Vincent.[96] On September 2, a baron of Hainaut, James of Avesnes, arrived overseas with some Flemings; “a soldier of great renown,” he became one of the crusade’s commanders.[94] The Bretons then completed their journey, and shortly afterward, in mid-September, various French barons appeared.[97] On the 24th, the Archbishop of Ravenna Gerard and the Landgrave of Thuringia Louis III arrived, the latter succeeding James of Avesnes as the crusade’s leader.[98] On September 29, the Londoners who had helped conquer Silves continued their journey through the Strait of Gibraltar and arrived at their destination some time later.[96] The last to complete their journey were other Danes, accompanied by an unspecified nephew of King Canute VI.[98]

Arrivals ceased during the winter but resumed in the spring of 1190. Count Henry II of Champagne, leading a large contingent composed of most of the forces of the French king Philip Augustus, arrived on July 27 and immediately took command.[98] Also arriving were some Normans, who distinguished themselves when they intercepted a Muslim ship with reinforcements and supplies for Acre on June 6, 1191.[98] The continuous and steady influx of men, ships, and various resources (including materials for building siege engines) continued throughout the months while awaiting the arrival of the three main European monarchs who had decided to participate in the crusade.[98]

Third Crusade and consequences

[edit]

Despite the involvement of the three aforementioned great European sovereigns, the outcome of the Third Crusade did not achieve its intended goals. Frederick Barbarossa did not even reach the Holy Land, as he died while fording the Saleph river in Cilicia,[99] while Philip Augustus of France and Richard I of England arrived at Acre by ship and provided support in the ongoing siege, capturing it in July 1191.[100]

The rivalry between Philip and Richard turned into a constant political struggle over which of the two sovereigns held supreme command.[101] This prompted Philip, who had also fallen ill, to return to his homeland with the promise not to attack Richard’s possessions in Normandy, a decision that sparked the anger of the English.[101][102] The Plantagenet sovereign thus remained the only monarch of the three who had come from Europe and led the remaining fighters southward, proving himself a skilled general.[103] Saladin noted his abilities in the Battle of Jaffa and Arsuf and seriously feared that Jerusalem was in danger.[104]

However, fearing he lacked sufficient forces to capture it and that it would be impossible to hold even if successful, the English king never attacked Jerusalem, causing widespread discontent among his ranks. His patience was tested by the disputes that arose among the Franks at Acre (such as the contention over the role of king of Jerusalem, disputed by Guy of Lusignan and Conrad of Montferrat),[105] and his health deteriorated due to the unhealthy Palestinian climate.[106] This prompted him to pursue diplomatic negotiations with the Muslims, which had never entirely ceased, but the English king’s skills in this area were not as adept as his military ones. When he learned that his brother John was causing problems in England due to his policies, Richard became convinced to return home.[106] Saladin, realizing that his troops were exhausted from such a grueling conflict, agreed to a truce, known as the Treaty of Ramla (September 2, 1192).[107][108] Under the terms of the agreement, ratified by Saladin the following day, the crusaders gained the coastal cities from Tyre to Jaffa.[106][107] Unarmed pilgrims were also granted access to Jerusalem’s holy sites, which remained in Saladin’s hands, and free passage for Muslims and Christians between the states was guaranteed; Ascalon was to be demolished and returned to the Saracens.[106][107]

Thus ended the Third Crusade, and Richard faced a journey as troubled as his outward one.[108] Saladin died shortly afterward, and internal conflicts soon erupted among his heirs vying for his legacy.[108] The Christian world’s dissatisfaction with the expedition’s outcome soon manifested, and new campaigns were organized. This was the case with the Crusade of 1197, led by Henry VI to fulfill the vow made by his father Frederick Barbarossa, which had not been realized, but this enterprise also proved inconclusive, despite the reconquest of Beirut.[109] The most significant and organized expedition after 1192 would not occur until 1204, with the Fourth Crusade.[110]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Arabs referred to Western Europeans collectively as Franks (Ifranj). The term should be understood as synonymous with "crusader."

- ^ According to Jean Richard, this event took place on November 23, 1161: Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ It remains a matter of historiographical debate whether Henry II truly intended to follow through on this promise. His death rendered the question moot: Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b c Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b c d Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b c d Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2022). The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). The Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ a b c Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ril131was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Grousset, René (1998). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem [History of the Crusades and the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem] (in French). Payot.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Flammarion.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2022). The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ a b c d e Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ a b c Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Flammarion. ISBN 978-0-674-28397-8.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Flammarion. ISBN 978-0-674-28397-8.

- ^ a b Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ a b c d e Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ a b Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ a b Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ a b Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ a b c d e Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2011). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ a b c d Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ a b c d e Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- ^ a b Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- ^ a b c d Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2022). The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ a b c Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.

- ^ a b c Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- ^ Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2022). The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bridge, Antony (2023). Dio lo vuole: storia delle crociate in Terra Santa [God Wills It: History of the Crusades in the Holy Land] (in Italian). Translated by Gianni Scarpa. Odoya. ISBN 978-88-6288-836-3.

- Eddé, Anne-Marie (2014). Saladin (in French). Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Flammarion. ISBN 978-0-674-28397-8.

- Grousset, René (1998). Storia delle crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Roberto Maggioni. Casale Monferrato: Piemme. ISBN 978-88-384-4007-6.

- Richard, Jean (1999). La grande storia delle crociate [The Great History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by Maria Pia Vigoriti. Rome: Newton & Compton editori. ISBN 978-88-798-3028-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2022). The Crusades: A History. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Runciman, Steven (2005). Storia delle Crociate [History of the Crusades] (in Italian). Translated by A. Comba; E. Bianchi. Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-17481-1.