Daniele Barbaro

Daniele Matteo Alvise Barbaro (also Barbarus) (8 February 1514 – 13 April 1570)[1] was an Italian cleric and diplomat. He was also an architect, writer on architecture, and translator of, and commentator on, Vitruvius.[2]

Barbaro's fame is chiefly due to his vast output in the arts, letters, and mathematics. A cultured humanist, he was a friend and admirer of Torquato Tasso, a patron of Andrea Palladio,[3] and a student of Pietro Bembo.[2] He was also friends with Pierre Arélin, Niccolô Franco, Bernardo Tasso, and Benedetto Varchi.[4] Francesco Sansovino considered Daniele to be one of the three best Venetian architects, along with Palladio and Francesco's father Jacopo.[5] Barbaro was praised as a man of science by Anton Francesco Doni, Cardinal Bernardo Navagero, Paolo Paruta, Sperone Speroni, and Bernardino Tomitano.[6] Francesco Barozzi dedicated his Opusculum to Daniele Barbaro.[7]

Biography

[edit]He was born in Venice, the son of Francesco di Daniele Barbaro and Elena Pisani, who was daughter of the banker Alvise Pisani and Cecilia Giustinian.[8] Barbaro studied philosophy, mathematics, and optics at the University of Padua[9] and became a member of the faculty there in 1540.[10] In 1545, Barbaro financed and supervised the construction of the University of Padua's botanical gardens and has been credited their design.[11] This is the world's oldest Botanical Garden.[12] A marble arch was later erected in his honor at the University.[13]

From 1548 to 1552 Barbaro served the Republic of Venice as ambassador to the court of Edward VI of England [14][15][16] His report on England and the English is considered one of the best written by any Venetian ambassador.[17]

In 1550, while still in England the Pope selected Barbaro as Patriarch of Aquileia[18][16][19] an ecclesiastical appointment that required the approval of the Venetian Senate. His appointment may have been secret (in pectore) to avoid causing diplomatic complications. Barbaro also served as a representative at the Council of Trent.[16][20][21] Barbaro was also elected official historian of the Republic of Venice, succeeding Cardinal Bembo.[22][23]

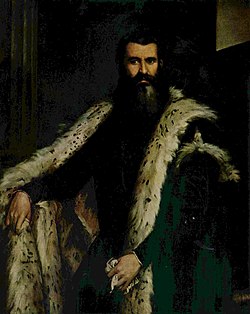

On the death of his father, he inherited a country estate with his brother Marcantonio Barbaro. They commissioned Palladio to design their shared country home Villa Barbaro, which is now part of a World Heritage Site. Palladio and Barbaro visited Rome together and the architecture of the villa reflects their interest in the ancient buildings they saw there.[24][25] The interior of the villa is decorated with frescoes by Paolo Veronese, who also painted oil portraits of Daniele; one reproduced in this article shows him dressed as a Venetian aristocrat, the other shows him in clerical dress.[26]

Barbaro died in Udine. His will refers to his collection of purchased and constructed astronomical instruments.[27] Daniele renounced his inheritance in favor of his brother Marcantonio and was buried in an unmarked grave behind the Church of San Francesco della Vigna instead of the family chapel there.[28] Daniele commissioned the church's altarpiece of The Baptism of Christ (c. 1555) by Battista Franco.[11]

Works

[edit]

Barbaro may have designed the Palazzo Trevisan in Murano, alone or in collaboration with Palladio. Like at the Villa Barbaro, Paolo Veronese and Alessandro Vittoria probably also worked on the project, which was completed in 1557.[11][29]

His works include:

- (1542) Exquisitae in Porphyrium Commentationes.[16]

- (1542) Predica de' sogni, published under the pseudonym of Reverend padre Hypneo da Schio.[16]

- (1544) Edited an edition of the commentaries on Aristotle's Rhetoric written by his great-uncle Ermolao Barbaro.[30][16]

- (1545) Edited an edition of Ermolao Barbaro's Compendium scientiae naturalis.

- (1556) An Italian translation with extended commentary of Vitruvius' Ten Books of Architecture, published as Dieci libri dell'architettura di M. Vitruvio.[2][31] The work was dedicated to Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este, patron of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli.[11][16]

- (1567) He later simultaneously published a revised Italian edition and a Latin edition entitled M. Vitruvii de architectura. The original illustrations of Vitruvius' work have not survived, and Barbaro's illustrations were done specially by Andrea Palladio, and engraved by Johann Chrieger. As well as being important as a discussion of architecture, Barbaro's commentary was a contribution to the field of aesthetics in general. El Greco, for example, owned a copy. Earlier translations had been made, by Fra Giovanni Giocondo (1511) and Cesare Cesariano (1521), but this work was considered the most accurate version to date. Barbaro clearly explained some of the more technical sections and discussed the relationship between nature and architecture, though he also acknowledged the way Palladio's theoretical and archeological expertise contributed to the work.[11][16] In his commentary, Barbaro shows knowledge of Pedro de Medina's Art of Navigation as well as the works of Leon Battista Alberti, Federico Commandino, Albrecht Dürer, Sebastian Münster, Johannes Stabius and Johannes Werner.[32]

- (1567) Dell'Eloquenza Dialogo[16]

- (1568) La pratica della perspettiva, a book on perspective for artists and architects.[11][16] This work describes how to use a lens with a camera obscura.[33]

- an unpublished and unfinished treatise on the construction of sundials (De Horologiis describendis libellus, Venice, Biblioteca Marciana, Cod. Lat. VIII, 42, 3097). The latter work was supposed to have discussed other instruments as well, including the astrolabe, the planisphere of Spanish mathematician Juan de Rojas, the navigation instrument cross-staff, the torquetum, an astronomical instrument and Abel Foullon's holometer, a surveying instrument.

See also

[edit]- Perfection (Aesthetic perfection)

- Portrait of Daniele Barbaro

- Barbaro family

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alberigo, Giuseppe (1964). "BARBARO, Daniele Matteo Alvise". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 6.

- ^ a b c Burke 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Burke 1998, p. 155.

- ^ "Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne", J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Michaud, 1811-28., pg. 331 [1]

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist art, Volume 1", Jane Turner, New York, 2000, pg. 112 [2] ISBN 0333760948

- ^ Venice and the Renaissance, Manfredo Tafuri, trans. Jessica Levine, 1989, MIT Press, p.126 [3] ISBN 0262700549

- ^ Venice and the Renaissance, Manfredo Tafuri, trans. Jessica Levine, 1989, MIT Press, p.133 [4] ISBN 0262700549

- ^ Tafuri, Manfredo (1989). Venice and the Renaissance. Translated by Levine, Jessica. Cambridge, Mass. ISBN 0-262-20072-4. OCLC 19123670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ Rose, Rose & Wright 1857, p. 136.

- ^ "Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne", J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Michaud, 1811-28., pg. 331 [5]

- ^ a b c d e f Turner 2000, p. 113.

- ^ "Palladio's architecture and its influence", Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi [6] ISBN 0486239225

- ^ "Rivista, Volume 1", Collegio araldico, 1903, pg. 365 [7]

- ^ "Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne", J Fr Michaud; Louis Gabriel Michaud, Paris, Michaud, 1811-28., pg. 330 [8]

- ^ "Rivista, Volume 1", Collegio araldico, 1903, pg. 365 [9]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rose, Rose & Wright 1857, p. 137.

- ^ "Palladio's architecture and its influence", Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi [10] ISBN 0486239225

- ^ "Renaissance education between religion and politics", Paul F. Grendler, Aldershot: Ashgate,2006, pg. 72, [11] ISBN 0860789896

- ^ "Palladio's architecture and its influence", Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi [12] ISBN 0486239225

- ^ "The Gentleman's magazine, Volume 223", London, 1867, pg. 737 [13] ISBN 0521651298

- ^ "Rivista, Volume 1", Collegio araldico, 1903, pg. 365 [14]

- ^ "Palladio's architecture and its influence", Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi [15] ISBN 0486239225

- ^ "Rivista, Volume 1", Collegio araldico, 1903, pg. 365 [16]

- ^ "Palladio's architecture and its influence", Joseph C. Farber, Henry Hope Reed, New York: Dover Publications, 1980, pg. xi [17] ISBN 0486239225

- ^ Venice and the Renaissance, Manfredo Tafuri, trans. Jessica Levine, 1989, MIT Press, p.129 [18] ISBN 0262700549

- ^ "Villa Barbaro: Architecture, Knowledge and Arcadia". Australian National University. 2003. Archived from the original on 9 March 2004.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist art, Volume 1", Jane Turner, New York, 2000, pg. 113 [19] ISBN 0333760948

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist art, Volume 1", Jane Turner, New York, 2000, pg. 113 [20] ISBN 0333760948

- ^ Venice and the Renaissance, Manfredo Tafuri, trans. Jessica Levine, 1989, MIT Press, p.122 [21] ISBN 0262700549

- ^ Turner 2000, p. 112.

- ^ Grendler 2006.

- ^ Venice and the Renaissance, Manfredo Tafuri, trans. Jessica Levine, 1989, MIT Press, p.122 [22] ISBN 0262700549

- ^ "Renaissance vision from spectacles to telescopes", Vincent Ilardi, Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 2007, pg. 220 [23] ISBN 9780871692597

References

[edit]- Burke, Peter (2 November 1998). The European Renaissance: Centers and Peripheries. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-19845-1.

- Grendler, Paul F., ed. (1 January 2006). "XI: The Leaders of the Venetian State, 1540–1609: a Prosopographical Analysis". Renaissance Education Between Religion and Politics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-86078-989-5.

- Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John; Wright, Thomas (1857). A New General Biographical Dictionary. Vol. 3. T. Fellowes. pp. 136–137.

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław (1974). Petsch, D. (ed.). History of Aesthetics, vol. III: Modern Aesthetics. Translated by Kisiel, Chester A.; Besemeres, John F. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-90-279-3943-2.

- Turner, Jane (2000). Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist Art. Grove's Dictionaries. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1-884446-02-3.