Conspiracies in ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, evidence suggests that political conspiracies occasionally occurred within the royal palace, including plots against reigning monarchs. While most surviving texts are silent on internal struggles for influence, a limited number of historical and literary sources—some indirect, others more explicit—indicate instances of discord within the royal family. The polygamous nature of many pharaohs’ households, which often included numerous concubines residing in harem complexes, may have contributed to rivalries among royal women. In certain periods, these rivalries led to the formation of factions, with some individuals allegedly acting out of ambition or jealousy. These internal divisions sometimes culminated in plots against the king, typically with the aim of advancing the position of a secondary wife and her son in competition with the children of the Great Royal Wife.

During the Old Kingdom, the 6th Dynasty is associated with accounts of palace intrigue. According to the Egyptian priest and historian Manetho, Pharaoh Teti was assassinated by members of his own bodyguard. Archaeological evidence of a campaign of damnatio memoriae (erasure from history) supports the plausibility of this event. Pepi I is said to have survived a conspiracy, reportedly instigated by a royal wife, as recounted in the autobiography of Judge Ouni. The legendary figure of Queen Nitocris, mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus, is said to have avenged the assassination of her brother Merenre II by orchestrating the deaths of the conspirators, although the historical accuracy of this account remains debated. In the Middle Kingdom, the assassination of Amenemhat I is alluded to in two key literary sources: Instructions of King Amenemhat to his Son and the Story of Sinuhe. These texts imply that members of the royal household, including bodyguards, harem wives, and royal sons, may have been complicit. The writings suggest tensions surrounding the succession of Senusret I, the intended heir.

During the New Kingdom, the late 18th Dynasty witnessed episodes of political instability. The death of the Hittite prince Zannanza-Smenkhkare—possibly identified with Smenkhkare—during his journey to marry an Egyptian queen is regarded by some scholars as an assassination. The early 19th Dynasty saw speculation regarding the succession of Ramesses II. While earlier theories suggested he eliminated an elder brother, current scholarship considers this unlikely. Nevertheless, there may have been rivalries involving high-ranking officials, such as General Mehy, an adviser to Seti I. Following the death of Merenptah, succession disputes led to a series of conspiracies. Amenmes challenged his half-brother Seti II for the throne. The influential chancellor Bay supported the installation of the young king Siptah, before being executed on the orders of Queen Twosret, who was later overthrown by the general Sethnakht, founder of the 20th Dynasty. Ramesses III, considered a restorer of order, was himself the target of a major conspiracy. After a reign of over thirty years, he was assassinated in a plot involving Queen Tiye and her son, Prince Pentawer. The Judicial Papyrus of Turin documents the conspiracy, which implicated over thirty individuals, including palace officials, soldiers, priests, and magicians. Although the assassination was successful, the coup failed; Ramesses IV, the intended successor, ascended the throne.

Written sources

[edit]Egyptian Lexicon

[edit]The term "conspiracy", along with related terms such as "plot" and "conjuration", generally refers to a secret agreement among multiple individuals aimed at overthrowing an established authority, such as a government, or at targeting the life of a person in power, such as a head of state or high official.[1] In the context of ancient Egypt, the native language provides several terms that express similar concepts. These include iret sema ("to make a conjuration"), semayt ("enemy of the gods"), iret sebjou ("to make rebellion" against the pharaoh or the gods), and oua ("to meditate, devise, or plot".[2][3]

| Transcription | Hieroglyph | Translation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oua |

|

scheming, plotting | ||||||||

| ouat |

|

villains | ||||||||

| ouatou |

|

plotters | ||||||||

| sebit |

|

rebellion | ||||||||

| sebi |

|

rebel | ||||||||

| semayt |

|

group, troop, band | ||||||||

| sema |

|

to kill, to murder | ||||||||

| semat |

|

murderer |

Egyptian Texts

[edit]

Based solely on Egyptian textual sources, confirmed cases of pharaohs being assassinated as a result of conspiracies appear to be rare. Only two such incidents are clearly documented: the murder of Amenemhat I of the 12th Dynasty and that of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty. These two cases stand out among approximately 345 known rulers over Egypt’s 3,000-year dynastic history. The assassination of Amenemhat I is referenced in Instructions of King Amenemhat to his Son, a didactic text in which the deceased pharaoh is portrayed as addressing his son and successor, Senusret I, from the afterlife. The composition exists in several manuscript versions, the earliest dating to the 18th Dynasty, including the Millingen and Sallier II papyri. According to tradition, the scribe Khety authored the text shortly after Senusret’s accession. Widely regarded as a cornerstone of royal ideology, it remained in circulation for centuries and is even found in school exercises—often with significant errors—on ostraca up to the 30th Dynasty.[4] Another literary classic, the Story of Sinueh, indirectly alludes to a conspiracy at the time of Amenemhat I’s death. In the narrative, the protagonist overhears a clandestine conversation between plotters. Alarmed, he flees Egypt out of fear that he may be implicated, thereby providing insight into the atmosphere of political tension during the transition of power.[5]

The assassination of Ramesses III is more explicitly documented in what is commonly referred to as the "Harem Conspiracy". Contemporary judicial sources provide detailed accounts of the event. These include the Lee and Rollin papyri, the Rifaud texts, and most notably, the Judicial Papyrus of Turin. The latter contains records of legal proceedings against approximately thirty conspirators, categorized according to their level of involvement. Although the texts are couched in euphemistic and formulaic language—reflecting the gravity and taboo nature of regicide—they nevertheless confirm that the conspirators included individuals from within the royal household and administrative elite. Their names are often distorted in derogatory ways, but their official titles indicate their close proximity to the pharaoh.[6]

Other testimonials

[edit]This very limited number of documented conspiracies can be supplemented by accounts from Greek sources, though these are not corroborated by Egyptian records. Herodotus reports that Queen Nitocris avenged the murder of her brother by executing the conspirators (Histories II, 100),[7] suggesting that Merenre II may also have been assassinated. According to Manetho, King Teti (referred to as Othoes) was killed by his own bodyguards (Aegyptiaca, fr. 20–22),[8] a claim partially supported by archaeological evidence indicating the involvement of some members of his court. Similar suspicions surround Pepi I's entourage. Manetho also attributes the assassination of Amenemhat II by his eunuchs (Ægyptiaca, fr. 34–37).[9] A possible regicide in the 18th Dynasty has been proposed, not involving Tutankhamun, as is sometimes speculated, but rather his little-known predecessor, Smenkhkare. The identity of Smenkhkare remains uncertain; he is sometimes associated with Prince Zannanza, a Hittite royal mentioned in sources such as the Deeds of Šuppiluliuma and Mursili’s Prayer to All the Gods, which recount diplomatic correspondence between Emperor Šuppiluliuma and an unnamed Egyptian queen, likely, Akhenaten's widow.[10] Other pharaohs are known to have died violently, though historical sources do not explicitly link their deaths to conspiracies. These include Narmer, who is said to have died during a hunt; Senebkay and Bakenranef, who perished during conflicts between rival dynasties; Seqenenre Tao, killed during warfare with the Hyksos; Apries, during dynastic strife; Ptolemy XI, who was lynched by a mob; and Ptolemy XV Caesarion, who was executed by order of the Roman emperor Augustus.[11]

Mythological background

[edit]The Issue of Regicide

[edit]In ancient Egypt, as well as in several pre-colonial African kingdoms, regicide often carried a cosmo-mythological dimension. Among the Moundang of Chad, the king of Léré was ritually executed after seven years of rule, based on the belief that he would otherwise lose his ability to influence meteorological phenomena. Similarly, among the Shilluk of the White Nile, the king of Fachoda was reportedly executed by his guards upon recommendation from the royal wives when he was no longer considered physically capable of fulfilling his marital duties. These practices reflected a broader concern that the physical decline of a monarch could symbolically endanger the well-being of the entire community through a process of mimetic deterioration.[12] In ancient Egypt, such ideas were reflected in mythology, particularly in the Osiris myth, which played a central role in legitimizing pharaonic kingship. According to the myth, Osiris, the divine king, was killed in the 28th year of his reign as part of a plot orchestrated by his brother Set-Typhon. Set had secretly measured Osiris's body and commissioned the construction of a lavishly decorated chest to match his dimensions. At a banquet, Set promised to gift the chest to anyone who fit it perfectly. When Osiris lay down inside, the conspirators sealed the chest and cast it into the sea:

At the sight of this chest, all the guests were astonished and delighted. Typhon then jokingly promised to make a present of it to whomever, by lying down in it, filled it exactly. One after the other, all the guests tried it on, but none of them found it to their liking. Finally, Osiris entered and stretched himself out on it. At the same moment, all the guests rushed to close the lid (...) Once the operation was completed, the chest was carried up the river and lowered into the sea.

— Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris, excerpts from §. Translation by Mario Meunier[13]

Following Osiris's death, the narrative focus in texts such as The Contendings of Horus and Set shifts from punishment to succession.[n 1] A divine tribunal presided over by Ra was tasked with determining the rightful successor. The contest was between Set, a mature and powerful deity, and Horus, the youthful son of Osiris, who based his claim on hereditary legitimacy. Over many years, the two engaged in various contests. Ultimately, the tribunal ruled in favor of Horus, who was supported by Osiris from the afterlife, symbolizing his continued influence over agricultural fertility and divine order.[14]

In historical terms, three well-documented cases of regicide in ancient Egypt include the assassinations of Teti (6th Dynasty), Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty), and Ramesses III (20th Dynasty). Each of these rulers had reestablished dynastic authority and were of advanced age at the time of their deaths—Amenemhat and Ramesses are estimated to have been in their seventies. In the case of Ramesses III, modern medical analysis has revealed a serious heart condition that may have left him physically weakened. In all three cases, the conspiracies appear to have been timed at moments when the king's perceived sacred authority had waned. Notably, these events occurred shortly before the Sed Festival, a royal jubilee ritual intended to rejuvenate the king's divine and physical vitality, traditionally celebrated after thirty years of reign.[15]

Rules of Succession

[edit]

Ancient Egypt was a patriarchal society in which authority was primarily held by men, although women retained certain rights and freedoms. Across all social strata, sons were generally expected to inherit their father's profession. In the royal context, succession ideally passed to a son of the Great Royal Wife, but in the absence of such an heir, sons of secondary wives could also ascend to the throne.[16] The accession of a woman to the highest office was rare and typically associated with periods of dynastic instability or succession crises, such as in the cases of Nitocris and Sobekneferu, or when dynastic continuity was threatened by consanguinity, as with Hatshepsut, Neferneferuaten, and Twosret.[n 2]

Although Egyptian royalty did not have a codified system of succession, the Osiris myth provided a prevailing model: "Let the inheritance be given to the son who buries, according to the law of Pharaoh".[17] Royal funerals were held under the symbolic protection of Horus, son of Osiris. In this framework, a son’s role was to honor his deceased father by organizing his burial and sustaining his funerary cult. Applied to royal succession, the myth justified inheritance from father to son, with the living pharaoh (Horus) legitimized through his filial act toward the deceased pharaoh (Osiris). Accordingly, every new ruler was expected to attend his predecessor’s funeral to assert his legitimacy.[18] Biological descent, while relevant, was often secondary to ritual acknowledgment. More significant was the recognition of one's predecessor as a spiritual or symbolic father, affirmed by participating in funerary rites. For instance, Pharaoh Ay, who ascended the throne at around sixty years of age following the death of the young Tutankhamun, fulfilled the ritual and symbolic functions of a son, despite being of a generation that could have made him Tutankhamun’s grandfather.[19]

Becoming pharaoh required more than coronation—it necessitated presiding over the royal funeral. The physical presence of a royal body was therefore politically crucial.[n 3] In this context, the assassination of an aging ruler could be a strategic act, particularly if the designated heir was far from the court. The case of Amenemhat I illustrates this dynamic. Though attacked from a distance, his son Senusret I was quickly informed of the plot and hastened to the palace, where he took control of his father’s burial and succession. Thereafter, he consistently emphasized his filial piety in royal propaganda.[20] Beyond written accounts, royal succession in ancient Egypt was often influenced by charisma and internal competition, both among royal princes and within the palace elite and provincial administration. Ultimately, the candidate who secured the most support became pharaoh.[21] Symbolically, the dismembered body of Osiris was likened to the kingdom of Egypt itself. In reassembling Osiris’s body, Horus not only restored his father but also reconstituted the nation—each of the forty-two body parts representing one of the kingdom's forty-two regions.[22]

Cosmic Foes

[edit]

According to the ancient Egyptian belief in divine and immanent justice, moral actions attracted corresponding consequences: good brought good, and evil brought evil. The gods and the ancestors were thought to observe the actions of the living, and any wrongdoing was believed to invoke divine punishment. Pharaoh Khety III warned his son of this principle in a teaching that referenced the looting of the necropolis at Thinis: "I did a similar thing so that a similar thing happened".[23] This religious conception underpinned the legal framework of ancient Egypt and was especially evident in trials concerning regicide. In such cases, the pharaoh’s death was not interpreted as a sign of divine failure. Rather, the deceased king was portrayed as continuing to act from beyond the grave. Amenemhat I, for instance, addressed his son Senusret I in a didactic narrative known as The Instruction of Amenemhat, asserting his innocence and guiding his son. Similarly, in the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, it was Ramesses III—not his successor Ramesses IV—who was described as presiding over a tribunal composed of twelve judges, despite being deceased. In this context, the king speaks in the first person: "As for everything that was done, it was they who did it. May all that they have done fall on their heads! I am protected and exempted for eternity".[24]

Those convicted of conspiring against the king were depicted as the "abominations of the land." The act of shedding royal blood was considered a violation of cosmic and religious order—an offense against the gods themselves: "The abomination of every god and goddess, totally." Some of the accused were symbolically stripped of their identities through legal name changes that associated them with Apep, the primordial serpent and enemy of Ra, the sun god. Names such as Medsoure ("Ra hates him"), Panik ("the serpent-demon"), and Parêkamenef ("Ra the blind") underscored their exclusion from the social and divine order.[25] Egyptian belief held that the dead could harm one another in the afterlife, necessitating the eternal protection of the deceased king from enemies and accusers. To reinforce the king’s righteousness, his good deeds were publicly emphasized. Amenemhat I proclaimed his generosity: "There was no hunger in my years, and there was no thirst." In the Papyrus Harris I, Ramesses III catalogued his donations to temples, portraying himself as a benefactor. This narrative positioned the pharaoh as above reproach and shielded him from posthumous accusations. Conspirators were often portrayed as ungrateful, having betrayed a ruler who had shown them favor: "He neglected the many good things the king had done for him".[26] Evil, by its nature, was believed to invite obliteration. In the Old Kingdom, conspirators were subject to damnatio memoriae: their names were erased and their images defaced in their tombs. This symbolic destruction aimed to erase them both socially and magically. Once excluded from memory and ritual, these individuals were considered non-existent—banished from both the world of the living and the afterlife.[27][28]

Royal Palace

[edit]Crime Scenes

[edit]

Archaeology has revealed the existence of royal residences throughout ancient Egypt, dating from all historical periods, including Memphis (Old Kingdom), Lisht (Middle Kingdom), and Thebes, Pi-Ramesses (New Kingdom). The best-documented remains are the palace of Amenhotep III at Malkata and the royal residences of Akhenaten and Nefertiti at the city of Amarna. Several types of buildings can be identified according to their functions: governmental palaces, ceremonial palaces, and residential palaces.[29] The figure of the pharaoh was closely tied to the palace. The term "pharaoh" (Egyptian per-âa, meaning "Great House") originally referred to the royal palace itself. From the New Kingdom onwards, the term came to denote the person of the ruler through metonymy.[30]

Palace Guard

[edit]

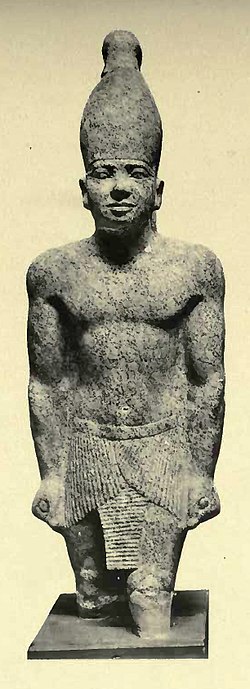

Many individuals were associated with the royal household, including servants, doctors, barbers, and craftsmen. In all periods, armed protection was necessary to ensure the safety of the sovereign.[29] This responsibility fell under the administration of the setep-sa, a term meaning "to escort, guard, or watch over," and by extension, "royal palace".[31] The structure of palace security, particularly in the earliest periods, remains difficult to reconstruct. During the Old Kingdom, the pharaoh was likely protected by a corps known as the Khentyou-she or Khentyou-she-khaset, translated as "Those who are in front of the gardens" and "Those who are in front of the gardens and mountains," respectively. This military unit was not limited to guarding the palace; it also secured royal funerary complexes and estates. Members of this corps served the king by producing agricultural goods, participating in royal hunts, and transporting resources to the palace. The guard operated within a hierarchical system, allowing capable individuals to rise through the ranks. Some viziers, such as Mereruka under Teti and Tjejou under Pepi I, began their careers in this corps.[32]

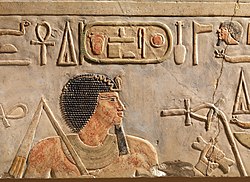

However, the loyalty of the palace guard was not guaranteed. In several well-documented conspiracies, members of the guard were directly involved. Teti and Amenemhat I were both assassinated in acts of treachery, and Pepi I reportedly survived two such plots. The royal administration, in response, maintained a general climate of suspicion.[28] In the Teaching for Merikare, Pharaoh Kheti III instructs his son to command the loyalty of his entourage and to suppress any signs of sedition.[33] The Story of Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhat situate the conspiracy against Amenemhat I within the royal palace at Lisht. On the night of 7 Hathor, year 30 of Amenemhat's reign (circa February 13, 1958 BCE),[34][n 4] the conspirators attacked, killing the palace guard and assassinating the king, who had been roused from sleep by the sound of weapons. Prior to the assassination, Sinuhe served as a shemsu, or "follower," an armed guard responsible for palace security and associated with the royal harem. After overhearing a conversation between two plotters, he realized the gravity of the political murder and fled into the desert, fearing he might be mistaken for a conspirator.[35]

Harem

[edit]

From the earliest periods, royal prestige in ancient Egypt was reflected in the practice of polygamy. Pharaohs were typically surrounded by a significant number of wives.

The royal harem, referred to in Egyptian as ipet-nesout ("king’s apartment") and per khener ("house of seclusion"), functioned as a parallel institution to the official royal administration. It housed the Great Royal Wife, secondary wives, and concubines. These women were referred to as khekerut nesut ("the king’s ornaments") and neferut ("the beauties"). Also residing in the harem were royal children and their nurses, the widows of deceased pharaohs, and a large number of attendants and servants. The institution was typically overseen by the Great Royal Wife or, in some cases, the Royal Mother.[36]

During times of dynastic instability, some women ascended to pharaonic power, including Nitocris, Sobekneferu, Hatshepsut, and Twousret. Numerous other women within the royal entourage played roles in political affairs. Competition among wives and concubines in the harem was often intense. As early as the Old Kingdom, textual evidence indicates that conspiracies occasionally formed around prominent women. Under the reign of Pepi I, the official Ouni was tasked with secretly investigating the conduct of a queen involved in a suspected conspiracy within the harem. In the Instructions of Amenemhat, the king reflects on a plot against him and alludes to female involvement: "Since I had not prepared for it [the attack], I had not considered it, and my mind had not considered the imperiousness of the servants. Had women previously recruited henchmen? Is it from inside the palace that troublemakers are extricated?".[37]

Conspiracies in the 6th Dynasty

[edit]The Murder of Teti

[edit]

The founder of the 6th Dynasty was Pharaoh Teti, known in Greek sources as Othoes. His accession to the throne appears to have been problematic, as he was not the son of his predecessor, Unas. It remains uncertain whether he was a usurper or by what means he came to power. However, dynastic continuity was not entirely broken, as Teti was married to Princess Iput, a daughter of Unas, making him the son-in-law of his predecessor.[38] There may have been unrest at the beginning of his reign. His Horus name, Sehoteptaoui, meaning "He who pacifies the Two Lands", likely alludes to efforts at restoring internal order, possibly through military action. The precise length of his reign is unknown. The South Saqqara Stone attests to at least 12 years, while the Ptolemaic historian Manetho, writing in the 2nd century BCE, claims that Teti ruled for thirty years before being assassinated by his bodyguards:[39]

The sixth dynasty consisted of six kings from Memphis.

1. Othoes for thirty years: he was assassinated by his bodyguards.— Manetho, fragment 20.

According to Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati, who led archaeological excavations of Teti's burial complex, several findings suggest that the king may indeed have been the victim of a conspiracy. Studies of the mastabas and tombs of his officials indicate that Teti took extraordinary measures for his personal security. The number of palace guards was significantly increased, and the service reorganized, with recruitment focused on a small circle of allied families, reflecting royal mistrust.[40] Additionally, many of the tombs from this period show evidence of deliberate defacement, likely part of a campaign of damnatio memoriae initiated early in the reign of his successor, Pepi I, Teti’s legitimate son. Numerous palace guards and servants were denied posthumous honors. This included individuals such as the guards Semdent, Irénakhti, Méréri, Mérou, and Ournou, the judge Iries, and the administrator Kaaper. Some tombs remain unfinished; in others, names were erased or figures were damaged, especially at the head and feet. Among the most senior disgraced officials were the vizier Hesi, the weapons supervisor Meréri, and the chief physician Séânkhouiptah.[41]

Userkare the Usurper

[edit]Teti's immediate successor was Pharaoh Userkare, whose reign was brief, lasting approximately one year. It remains uncertain whether Userkare was a son of Teti—possibly through a queen or concubine—or whether he had no direct dynastic claim. His name appears in both the Turin King List and the Abydos King List. Nevertheless, the possibility that he was a usurper is widely considered. His accession may have occurred through violent means, and he was likely deposed within months by a faction loyal to the legitimate royal line.[42] Evidence supporting this interpretation includes the absence of any mention of Userkare in the tomb inscriptions of high-ranking officials such as the viziers Inoumin and Khentika, who served under both Teti and Pepi I.[43] Additionally, the tomb of Méhi, a palace guard who served under Teti, Userkare, and Pepi I, contains inscriptions indicating that Teti’s name had been erased and replaced with that of another king—presumably Userkare. This name was later removed and replaced again with Teti’s.[44] The evidence suggests that Méhi may have transferred his allegiance from Teti to Userkare and, following Pepi I’s accession, attempted to realign with the legitimate royal line. This effort appears to have failed, as construction on his tomb was abruptly halted, and he was never buried there.[45]

Conspiracies under Pepi I

[edit]

According to Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati, two conspiracies took place during the reign of Pepi I. The first appears to have occurred early in his reign. The biography of the high official Weni (also known as Uni), inscribed in his mastaba at Abydos, records that a secret trial was held within the royal harem to investigate the conduct of a royal wife. Although the exact charges and outcomes are not specified, the case appears to have been of considerable seriousness:[46]

His Majesty appointed me Government Officer at Hiéracônpolis, because he trusted me more than any of his servants. I listened to the quarrels being alone with the vizier of the State in every secret affair and every thing that touched the name of the king, the royal harem, the tribunal of the Six (...). There was a trial in the royal harem against the royal wife, a great favorite in secret. His Majesty asked me to judge the case alone, without any State vizier or magistrate except myself, because I was capable, because I was successful in His Majesty's esteem, because His Majesty had confidence in me. It was I who put the minutes in writing, being alone, with a Government Officer in Hieracônpolis who was alone, even though my function was that of director of the employees of the great palace. No one in my position had ever heard a secret of the royal harem before, but His Majesty made me listen to it, (...).

— Biography of Ouni (excerpts). Translation by Alessandro Roccati.[47]

The precise length of Pepi I’s reign is uncertain. The historian Manetho credits him with a reign of fifty-three years,[48] while modern Egyptologists estimate a duration ranging from thirty-four to fifty years.[49] According to the Austrian Egyptologist Hans Goedicke, the trial took place in the 42nd year of the reign and involved a plot by the mother of Merenre I, Pepi's successor.[50] However, this theory is rejected by Naguib Kanawati, who argues that archaeological evidence points instead to a separate conspiracy around the 21st year of Pepi’s reign. This second conspiracy appears to have involved several courtiers, many of whom were the sons of men formerly trusted by Teti. The plot was likely orchestrated by Vizier Raour, whose tomb lies within Teti’s necropolis. Raour was the son of Shepsipouptah, a son-in-law of Teti. The conspiracy ultimately failed, and Raour was condemned.[51] His name and image were subsequently erased from his tomb as part of a damnatio memoriae.[52] While the specific goals of the conspiracy remain unclear, it is probable that the plotters intended to assassinate Pepi I and replace him with one of his sons.[53]

Revenge of Queen Nitocris

[edit]According to some ancient Greek historians, the 6th Dynasty ended with the reign of Queen Nitocris (Greek form of Neitiquerty). This claim should be treated with caution. The dynasty ruled around the 21st century BCE, while the sources citing these events, such as those by Herodotus and Manetho, date from almost 2,000 years later. The Ptolemaic historian Manetho of Sebennytos provides a highly romanticized portrait of the queen: "A certain Nitokris reigned, the most energetic of men and the most beautiful of women of her time, blonde with rosy cheeks. It is said that the third pyramid was built by the latter, ostensibly showing the aspect of a hill" (Ægyptiaca, fr.20–21).[54]

Herodotus also attributes dramatic actions to Nitocris. According to him, the penultimate pharaoh—likely Merenre II—was murdered in a conspiracy. Nitocris, identified as his sister, is said to have taken the throne and avenged his death by luring the conspirators to a banquet, where she drowned them by releasing Nile water through a hidden canal. Afterward, she allegedly committed suicide by leaping into a chamber filled with burning embers:[55]

They told me that the Egyptians, after having killed her brother, who was their king, gave her the crown; that she then sought to avenge his death, and that she killed a large number of Egyptians by artifice. [...] she let in the waters of the river through a large secret canal. [...] Nothing more is said about this princess, except that after doing this she rushed into an apartment covered in ashes, in order to escape the vengeance of the people.

— Herodotus, Histories – Book 2, 100. Translation by Larcher.[56]

No Egyptian sources confirm this episode, and as such, it remains impossible to determine whether it reflects a historical event or a later anecdotal tradition.[57] Archaeological evidence has yet to verify the reign of Nitocris or the alleged assassination of Merenre II. Nevertheless, the historical existence of a ruler named Neitiquerty is supported by fragment 43 of the Turin King List. However, it remains uncertain whether this name refers to Queen Nitocris or to a male ruler, possibly King Netjerkarê.[58]

Assassination of Amenemhat I

[edit]Tragic Night at the Palace

[edit]

The assassination of Amenemhat I in the 30th year of his reign, and the turbulent circumstances under which his eldest son Senusret I succeeded him, are documented in two major literary sources: the Story of Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhat to his Son. At the time of the king's death, preparations were underway for his first Sed-festival, a ritual intended to renew his divine authority. However, Amenemhat had yet to publicly designate a successor, creating uncertainty within the royal court.[59] His natural heir and co-regent, Prince Senusret, was absent from the capital, engaged in military campaigns in the Libyan desert—likely to conduct raids that would fund the extravagant costs of the upcoming jubilee.[60] Amid this context, a major conspiracy unfolded. One night, members of the palace guard, specifically those associated with the harem, rebelled and entered the royal apartments, ultimately assassinating the pharaoh. This dramatic event is recounted in the Instructions of Amenemhat, a text in which the deceased king speaks from beyond the grave:[61]

It was after dinner, after dark. As I had taken a moment to relax, I lay down on my bed, let myself go, and my mind began to follow my somnolence. So the weapons of protection were set in motion against me, and I found myself treated like a desert snake. When I awoke to the fight and regained my senses, I realized that it was a battle involving the bodyguards. As for the fact that I rushed in with weapons in hand, I made the cowards retreat under the blows. But there are no brave men at night, there are no lone fighters. Success cannot come without a protector.

— Instructions of Amenemhat to his son. Translation by Pascal Vernus.[62]

At the beginning of the Story of Sinouhe, it is recounted that Senusret was informed of the attack by a messenger while still on campaign. He likely also learned that several of his brothers, present in the army, may have been involved in the conspiracy. Without alerting anyone, he returned hastily to the palace, leaving his forces behind, fearing he might also become a target. The exact means by which he regained control of the government or secured the throne remain unknown. It is, however, historically attested that the early years of Senusret I’s reign were marked by civil unrest, and that he was compelled to suppress factions opposed to his rule with considerable force.[63]

Crime suspects

[edit]Instructions of Amenemhat to His Son and the Story of Sinuhe suggest that members of the royal family were involved in the conspiracy. In the former text, Amenemhat I, speaking from the afterlife, gives his son Senusret I cautious advice. The pharaoh is portrayed as a lonely figure, devoid of loyal family, friends, or servants:

So beware of subjects who don't come forward and for whom no one has worried about the terror they may inspire. Do not approach them when you are alone. Don't trust a brother. Keep away from friends. Don't make friends. There's no point! When you sleep, let your own heart watch over you, for a man has no followers on the day of trouble.

— Instructions of Amenemhat to his son, (excerpt). Translation by Claude Obsomer.[64]

Unless a judicial papyrus—like that which details the conspiracy against Ramesses III—is discovered, the names of the plotters and the rival brother who opposed Senusret I may never be known. Still, one plausible hypothesis has been proposed. Amenemhat I’s accession remains somewhat obscure, but it is widely accepted that he rose from the position of vizier to become pharaoh. He founded the 12th Dynasty at Lisht, succeeding Mentuhotep IV, the last ruler of the 11th Dynasty, based in Thebes.

In 1956, Georges Posener proposed that the plot may have originated in Thebes. The rival brother may have been the son of a secondary wife of Amenemhat I and a descendant of the Theban Mentuhotep line. If so, the conspiracy might have aimed to restore the royal court and administrative power to Thebes.[65] Further speculation was offered by Lilian Postel in 2004. She noted that the identity of King Qakarê Intef remains uncertain.[66] Known only through graffiti in Lower Nubia, his name—Intef—was borne by several rulers of the 11th Dynasty, and his Horus Name – Sénéfertaouyèf (He who makes the two lands beautiful) – is very close to the Horus Name – Séankhtaouyèf (He who invigorates his two lands) – of Mentuhotep III, the last great representative of the 11th Dynasty. Under these circumstances, and with due caution, it is tempting to associate this figure with the unrest reported in Upper Egypt at El-Tod and Elephantine early in Senusret’s reign.[67]

Murder of Amenemhat II

[edit]

With regard to the 12th Dynasty, the historian Manetho reports the assassination of a pharaoh named Ammanemês—that is, Amenemhat. However, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that this is not Amenemhat II, whose death is described in Egyptian literary sources, but rather his grandson, Amenemhat II, the son of Senusret I:

The 11th dynasty comprised sixteen pharaos from Thebes who reigned for forty-three years. After them, Ammenemês assumed the role during sixteen years (…). The twelfth dynastie comprised seven pharaos from Diospolis

1. Sesonchosis, son of Ammenemês

2. Ammanemês, for thirty-eight years: he was murdered by his own eunuchs.

3. Sesôstris, for forty-eight years (…)— Manetho, Ægyptiaca, fr. 32 and 34.[68]

Interpreting this statement is complex. Manetho’s original work is lost; what survives are epitomes—quotes or summaries of his writings—passed down by Jewish and Christian authors from the first centuries CE. As a result, it is difficult to reconstruct Manetho’s exact views. Egyptologists generally believe that Manetho may have confused Amenemhat II with Amenemhat I, whose assassination by palace guards is well attested in Egyptian sources. Such a mistake would not be unusual, given the numerous inconsistencies in Manetho’s accounts, especially regarding reign lengths. Nonetheless, the possibility of a second regicide during the 12th Dynasty cannot be entirely ruled out. Manetho’s report of Teti’s assassination (under the Greek name Othoes) is now widely accepted by scholars despite the lack of corroborating Egyptian texts. Archaeological evidence—such as damaged tombs and damnatio memoriae—supports the claim. The same could conceivably apply here.[69]

At present, Amenemhat II’s reign remains poorly documented, and many aspects of his rule are uncertain. He ruled for at least thirty-five years, a figure that aligns reasonably well with Manetho’s claim of thirty-eight years. His reign appears to have been marked by diminished central authority and growing competition from powerful provincial governors.[70]

The Zannanza Affair

[edit]The Murder of a Hittite Prince

[edit]

According to Hittite records, following the death of the Egyptian pharaoh—identified in Hittite texts as Nipkhourouriya[n 5]—his widow sent a diplomatic message to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I. The letter stated:

My husband is dead. I have no sons. But they say your sons are many. If you give me one of your sons, he will be my husband. I will never take one of my servants as my husband! [...] I'm afraid.

— Geste de Shouppilouliouma.[71]

After initial hesitation and inquiries to confirm the sincerity of the proposal, Suppilliuma agreed to the request and dispatched one of his sons, Prince Zannanza, to Egypt. However, according to Hittite archives, Zannanza never arrived. Reports sent to the Hittite court claimed that he had been killed en route. It is believed that an Egyptian faction opposed to the alliance may have orchestrated his assassination:

When they brought this tablet, they spoke thus: "The men of Egypt have killed Zannanza" and reported this: "Zannanza is dead". And when my father heard the news of Zannanza's murder, he began to lament about Zannanza and, addressing the gods, he spoke thus: "O gods! I have done nothing wrong, yet the men of Egypt have done this against me, and what's more, they have attacked the border of my country!"

— Mourshilli's II prayers against the plague.[72]

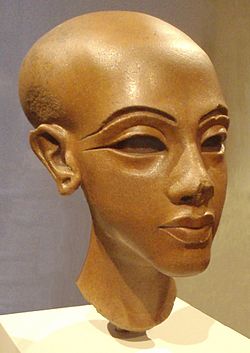

Merytaton's Intrigues

[edit]

The Hittite texts refer to the Egyptian queen as Dakhamunzu, meaning "The King's Wife".[73] Her precise identity remains uncertain. Egyptologists have suggested several possible figures, including Nefertiti, Kiya, Meritaten, and Ankhesenamun.[74] According to Marc Gabolde, a scholar specializing in the 18th Dynasty and the Amarna period, the most plausible candidate is Meritaten, the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Meritaten became Great Royal Wife after her mother's presumed death in the sixteenth year of Akhenaten's reign.[n 4] Akhenaten himself died shortly thereafter, in year 17.[75]

In the ensuing power vacuum, Meritaten—or her political faction—may have sought to consolidate power by excluding rival claimants, such as the young prince Tutankhamun, who was likely between four and six years old at the time.[76] In an attempt to form a strategic alliance, Meritaten is believed to have contacted the Hittites, requesting a royal consort to legitimize her position. Prince Zannanza was sent for this purpose, and according to some interpretations, priests in Meritaten’s circle even prepared a royal title for him: Ânkhéperourê Smenkhkarê.[n 6] However, the prince was either assassinated en route or died shortly after arrival, preventing his installation as pharaoh. Following this, Meritaten appears to have assumed the throne herself under the regnal name Ânkhetkhéperourê Nefernéferouaton.[n 7] Her reign was brief, lasting approximately three years. Her ultimate fate remains unknown, and her burial site has not been identified. Nor do we know where she was buried. It probably wasn't very sumptuous, or it would have been discovered by now. After her disappearance from historical records, Tutankhamun assumed the throne, supported by influential figures such as Ay and Horemheb.[77] The identity of those responsible for Zannanza’s death remains a subject of debate. One possible suspect is General Horemheb, who held command of the Egyptian military at the time.[78]

Twilight of the 18th Dynasty

[edit]The death of Tutankhamun

[edit]

Tutankhamun, one of the most well-known pharaohs of ancient Egypt, owes his modern fame largely to the discovery of his nearly intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922. Analysis of his mummy has established that the young king died between the ages of sixteen and seventeen, likely within the first months of his tenth regnal year.[79] The absence of contemporary Egyptian textual evidence regarding the cause of death has led to a range of modern hypotheses, including murder, accident, or illness. The theory that Tutankhamun was assassinated was first proposed in 1971 by R. G. Harrison of the University of Liverpool. Following an X-ray examination of the mummy conducted in 1968, Harrison reported the presence of a bone fragment embedded in the skull's resin deposits. This was interpreted as evidence of a fatal blow to the back of the head, suggesting the young pharaoh may have been deliberately killed.[80] The hypothesis was later supported by Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves, who explored the possibility in his 1990 publication on Tutankhamun.[81]

In 2006, American crime investigators Gregory M. Cooper and Michael C. King applied modern criminal profiling techniques and suggested possible suspects, including the treasurer Maya, Queen Ânkhésenamon, the "Divine Father" Ay and General Horemheb—two of whom (Ay and Horemheb) would later succeed Tutankhamun on the throne.[82] However, the assassination theory was re-evaluated in light of new evidence. As early as 2002, a critical reassessment of the 1968 radiographs challenged the validity of the skull trauma interpretation.[83] In 2005, a multidisciplinary team conducted a high-resolution CT scan of the mummy. These scans found no evidence of cranial trauma, effectively ruling out the earlier theory of a fatal head injury. Instead, the analysis revealed that the king had suffered a severe compound fracture in his left leg shortly before death. Given his poor general health, including signs of genetic disorders and a compromised immune system, it is now believed that Tutankhamun likely died from complications related to this leg injury—specifically, sepsis resulting from infection.[84]

Eviction of Prince Nakhtmin

[edit]

The final years of Egypt's 18th Dynasty were characterized by dynastic instability and intense political competition. Pharaoh Tutankhamun ascended the throne as a child, likely between six and seven years old, and died without an heir before reaching his twenties. His untimely death created a power vacuum that enabled individuals outside the immediate royal family to claim the throne. Four key figures emerged during this transitional period: the royal advisor Ay, and three prominent military officials—Horemheb, Nakhtmin, and Paramessu. Ay and Horemheb held the highest governmental offices under Tutankhamun. Upon the king’s death, Ay assumed the throne and initially maintained a tense but non-confrontational relationship with Horemheb, continuing the dynamics of their previous roles. However, this balance soon shifted. Horemheb engaged in several propagandistic efforts to bolster his own legitimacy, including inscriptions on statues emphasizing his administrative competence. These actions appear to have been aimed at undermining Ay’s authority as pharaoh. At the same time, Ay, already an elderly man, began to prepare for his succession by elevating Nakhtmin—likely his son or nephew—as crown prince and assigning him important state duties, some of which may have previously been overseen by Horemheb. The exact timing of Nakhtmin’s promotion remains unclear, but it may have led to growing tensions and rivalry between the two factions. There is no definitive evidence that Horemheb actively deposed Ay, who died after a short reign of approximately four years. Despite Nakhtmin being designated as Ay’s successor, it was Horemheb who ultimately ascended the throne. The circumstances surrounding this transition remain uncertain. There is no direct documentation that Horemheb physically removed Nakhtmin from power, nor is it known whether Nakhtmin died of natural causes prior to Ay’s death.[85]

However, if Nakhtmin was still alive at the time, his exclusion from the throne may indicate a successful political maneuver by Horemheb during the transitional period. One hypothesis suggests that Nakhtmin may have been overseeing Ay’s funeral and preparing for coronation when Horemheb seized the opportunity to assume power.[86] After consolidating his rule, Horemheb initiated a damnatio memoriae against Ay and his supporters. This included erasing their names and images from monuments and official records. Queen Ânkhésenamun, the widow of Tutankhamun, was also subjected to erasure from public memory.[87] Horemheb reigned for several years and designated his vizier, Paramessu, as his successor. Upon Horemheb’s death, Paramessu ascended the throne under the name Ramesses I, thereby founding the 19th Dynasty and inaugurating a new era in ancient Egyptian history.[88]

Ramesses II and the question of Dynastic rivalry

[edit]The suggestion that Ramesses II may have faced dynastic rivalry—possibly even from within his own family—has been popularized in modern historical fiction and has sparked scholarly debate. French writer and Egyptologist Christian Jacq explored this theme in his 1995–1996 pentalogy Ramesses, a series of historical novels that depict an elder brother, named Shenar, who was allegedly excluded from succession and came into conflict with Ramesses. The series was a commercial success, with approximately 13 million copies sold by 2004, including 3.5 million in France alone.[89][90] While fictionalized, Jacq’s narrative raises the broader question of whether Ramesses II’s claim to the throne was ever challenged, either before or during his long reign of 67 years.

The Méhy Case

[edit]

In 1889, James Henry Breasted noticed at Karnak a modified and then erased figure in a war scene depicting Seti I, father of Ramesses II, fighting Libyans. Breasted hypothesized that this figure represented an elder brother of Ramesses, removed from succession after Ramesses' accession. As the individual had no preserved name, Breasted referred to him as "X." In hypotheses published in 1905 and revised in 1924, Breasted suggested that Ramesses conspired to supplant this elder brother immediately following Seti I’s funeral.[91] For a time, the name Nebenkhasetnebet was proposed for this hypothetical prince. However, no conclusive evidence exists that Seti I had more than one son.[92]

In 1977, further excavations led Egyptologist William Murname to conclude that the Karnak figure was not a fallen prince but a soldier named Mehy, a commoner of unknown origin. Mehy was known for his logistical and organizational abilities, particularly during military campaigns. His proximity to Seti I appears to have been greater than his titles suggest. Although Mehy held influence at court, there is no evidence that he was designated as heir, a position previously filled by other commoners such as Ay, Horemheb, and Ramesses I before their ascensions. As Seti’s close associate, Mehy may have been viewed with suspicion or even fear by the young Ramesses—possibly even by Seti himself in his final years.[93] It is therefore plausible that Ramesses saw Mehy as a potential rival. Throughout his reign, Ramesses II repeatedly affirmed his legitimacy, possibly to deter members of the powerful military caste—Mehy or others—from challenging his authority.[94]

Treaty of Extradition

[edit]

Despite its exceptional length—sixty-seven years—the reign of Ramesses II was not marked by a large number of major military campaigns. During the first decade, five campaigns were conducted in the region of Syria-Palestine, notably including the famous battle of Kadesh (Year 5) and the siege of Dapur (Year 8).[n 4] Additionally, a raid into Libya occurred around Year 6 or 7, and a revolt in Nubia was suppressed in Years 19–20. Hostilities with the Hittite Empire (referred to in Egyptian and Hittite sources as the land of Khatti) appear to have ceased following the death of Hittite emperor Muwatalli II. He was succeeded by his son, Mursili III, who was eventually deposed by his uncle Hattusili III. The latter, seeking to legitimize his rule in the eyes of foreign powers, initiated diplomatic overtures to Egypt. These efforts culminated in the signing of a peace treaty with Ramesses II in Year 21 of the Egyptian king’s reign. The alliance was further strengthened by two diplomatic marriages, with Ramesses marrying Hittite princesses in Years 34 and 40.[95]

The treaty between Ramesses II and Hattusili III placed significant emphasis on the extradition of political refugees and conspirators. It detailed legal consequences for treachery, including capital punishment and mutilation. Although the treaty applied to both sides, it appears to have been primarily a Hittite initiative, aimed at securing the return of opponents to Hattusili. For instance, Mursili III, following his deposition, sought refuge in Egypt (Year 18), triggering a diplomatic incident:[96]

If an important man flees the land of Egypt and arrives in the land of the great master of the Khatti, or in a city or region belonging to the possessions of Ramesses-loved-of-Amon, the great master of the Khatti must not receive him. He must do what is necessary to deliver him to Ousermaâtrê Sétepenrê, the great king of Egypt, his master.

If one or two unimportant men flee and take refuge in the land of Khatti to serve another master, they must not be allowed to remain in the land of Khatti; they must be brought back to Ramesses-beloved-of-Amon, the great king of Egypt.

If an Egyptian, or even two or three, flee from Egypt and arrive in the land of the great master of Khatti, (...) in this case, the great master of Khatti will apprehend him and hand him over to Ramesses, the great ruler of Egypt: he will not be blamed for his mistake, his house will not be destroyed, his wives and children will live, and he will not be put to death. No injury will be inflicted on him, neither to the eyes, nor to the ears, nor to the mouth, nor to the legs. No crime will be imputed to him (follows the reciprocity clause on the Hittite side, using exactly the same terms).

— Treaty of Hittito-Egyptian (excerpt). Translation by Christiane Desroches Noblecourt.[97]

This clause was reciprocated by the Egyptian side using identical language, reflecting the mutual commitment to suppress political dissent and ensure regional stability.

Conspiracies of the 19th Dynasty

[edit]

The period between the death of Merneptah, son of Ramesses II, and the end of the 19th Dynasty was marked by approximately fifteen years of political instability. During this time, three pharaohs—Seti II, Amenmesse, and Siptah—and one queen, Twosret succeeded one another before Sethnakht, founder of the 20th Dynasty, ultimately seized power. For Ramesses III, only Seti II was considered a legitimate ruler in the interim between Merneptah and his father Sethnakht. This raises the question of why Amenmesse, Siptah, and Twosret were later regarded as illegitimate. Due to the scarcity and inconsistency of surviving documentation, this transitional period presents significant challenges for Egyptologists, particularly in reconstructing the genealogical relationships between these figures. Moreover, much of the political activity occurred in the capital, Pi-Ramesses, of which few archaeological remains have been recovered, and no archives have survived. It is generally accepted that all major political actors of the time were members of the Ramesside lineage. During his long reign of sixty-seven years, Ramesses II fathered an exceptionally large number of offspring, with at least fifty sons and fifty-three daughters known by name.[98] As a result, the number of his grandchildren was extensive, though remains largely undetermined due to the fragmentary state of the historical record. Many of these descendants held key positions within Egypt’s civil, military, and religious institutions. Following the death of Merneptah, pre-existing rivalries within the royal family escalated into open conflict. Several powerful factions emerged, each backing different descendants of Ramesses II. These internal disputes centered around the legitimacy of Merneptah’s successors and culminated in a series of successions that were contested both at the time and by later rulers. Seti II, Amenmesse, Siptah, and Twosret thus became central figures in a broader dynastic struggle, with only Seti II ultimately recognized as legitimate by the succeeding regime.[99]

Amenmes Revolt Against Seti II

[edit]

Upon the death of Merenptah, his son Seti II ascended the throne. Born to Queen Isetnofret, Seti was approximately twenty-five years old at the time of his accession.[100] The early months of his reign appear to have been relatively peaceful. However, this period of calm likely masked underlying familial tensions. Seti's authority was fragile, and it seems he faced internal challenges, particularly from the faction surrounding his wife Twosret. Twosret, designated as Great Royal Wife, is believed to have been a granddaughter of Ramesses II, either through her mother or father. Her considerable influence—and the apparent vulnerability of Seti II—may be reflected in the unusual location of her tomb (KV14) in the Valley of the Kings, situated near Seti’s own tomb (KV15), rather than in the Valley of the Queens where queens were traditionally buried.[101] The reason for this exceptional placement remains uncertain. Notably, around the time this privilege was granted to Twosret (late in Year 2 of Seti II's reign), the usurper Amenmesse emerged, suggesting that the increasing influence of the queen and her clan may have destabilized an already delicate familial balance.[102]

Amenmesse, whose origins lie within the Ramesside lineage, was probably the son of Queen Takhat, one of Merneptah's wives and a daughter of Ramesses II. This would make Seti II and Amenmesse half-brothers, transforming the political conflict into a dynastic rivalry.[103] Amenmesse had a degree of legitimacy and attracted substantial support, particularly in southern Egypt, including Nubia and Thebaid. Among his key backers was Roma-Roy, the influential High Priest of Amun in Thebes.[104] Although Amenmesse attempted to advance northward, his progress was halted near Abydos, a region that remained loyal to Seti II.[105] For a few years, Amenmesse maintained power in the southern part of the country, but Seti II eventually reasserted control. The fate of Amenmesse remains uncertain; he was likely eliminated by his rival, and he was never interred in the tomb prepared for him (KV10). No funerary cult for Amenmesse is attested archaeologically, indicating that he may have been deliberately consigned to oblivion.[106] Following his defeat, Amenmesse’s memory was subjected to damnatio memoriae, with his name erased from monuments. A broad administrative purge also took place in the Thebaid, removing all officials who had supported his regime.[107]

Plots of chancellor Bay

[edit]

The weakening of Seti II’s authority is reflected in the rapid ascent of the ambitious Chancellor Bay. Of Syrian origin, Bay experienced a meteoric rise within the Egyptian administration. He initially served as a royal scribe and cupbearer early in Seti II’s reign, and by the end, had attained the influential position of grand chancellor.[108] Seti II died in the sixth year of his reign without designating a successor, as his son, Prince Seti Merenptah, had predeceased him. This dynastic vacuum intensified existing rivalries within the Ramesside family. Two primary factions emerged: one centered around Queen Twosret, the king’s widow, and the other around Chancellor Bay, now the most powerful figure at court. For a time, Bay held the upper hand. It is widely believed that the young Siptah ascended the throne due to Bay’s influence. The chancellor even claimed credit for placing Siptah on the throne, stating that he had “established the king on his father’s throne".[109] Siptah, later regarded as illegitimate, was not a son of Seti II. His mother, a woman named Soterery, was also of Syrian origin. His father's identity remains uncertain, though he was likely Amenmesse, the half-brother of Seti II. Bay appears to have elevated a pliable figure to the throne in order to consolidate his own authority. Siptah was very young at the time of his accession—likely between twelve and fifteen years old—and suffered from a debilitating foot condition, possibly caused by a genetic disorder or poliomyelitis.[110] This physical limitation made it difficult for the young pharaoh to assert independent power. Bay thus established a system of dual governance, managing the administrative affairs of the state while Siptah performed the ceremonial and religious functions of kingship. Bay’s ambitions extended to the afterlife: he claimed the rare privilege of a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV13), located opposite that of Siptah (KV47), underscoring his exceptional status.[111] Initially, Queen Twosret was compelled to enter into a pragmatic alliance with Bay in order to maintain governmental continuity. However, by the fifth year of Siptah’s reign, tensions between the queen and the chancellor escalated. The power struggle culminated in Bay’s downfall. Branded a “great enemy”—a term denoting a traitor or conspirator—Bay was executed or assassinated. The exact circumstances remain unclear, and it is uncertain whether he faced a formal trial or fell victim to a plot orchestrated by Twosret and her allies.[112][113]

Rivalry between Sethnakht and Twosret

[edit]

Following the elimination of Chancellor Bay, Queen Twosret sought to consolidate her authority, although the young Siptah remained nominally pharaoh. The limited surviving documentation suggests that she may have aspired to establish a regency akin to that of Hatshepsut during the minority of Thutmose III.[114] However, Siptah died shortly thereafter, in the sixth year of his reign, at an estimated age of between twenty and twenty-five. The cause of his death is unknown. Upon his passing, Twosret assumed full royal authority and appears to have disregarded Siptah's reign, dating her regnal years not from his death but from that of her husband, Seti II.[115] The final phase of Twosret's rule is poorly documented. The latest attested date from her reign is Year 8, suggesting that her period of sole rule lasted less than two full years. Her successors, Setnakhte and Ramesses III, did not acknowledge her as a legitimate monarch.[116] A civil conflict likely erupted in the northern regions of Egypt, and the instigator appears to have been Setnakhte, founder of the 20th Dynasty. A member of the military elite, Setnakhte may have opposed the idea of a woman ruling Egypt. Notably, he dated the beginning of his reign not from his ultimate victory, but from the moment he initiated hostilities against Twosret following Siptah’s death.[117] Setnakhte’s ancestry remains obscure, and no existing records directly connect him to the Ramesside line. However, it is improbable that all surviving grandsons and great-grandsons of Ramesses II would have passively accepted the ascension of an entirely new royal house without opposition.[5] The prevailing hypothesis is that Twosret lost her grip on power amid conflict with the faction descended from Prince Khaemweset, with the influential vizier Hori likely supporting Setnakhte’s claim.[118] Nothing definitive is known about the circumstances of Twosret’s death. Despite the political turmoil, Setnakhte appears to have overseen her burial in tomb KV14, presumably as a strategy to legitimize his own rule.[119] He later appropriated KV14 for his own tomb, further consolidating his royal image.[120] Interestingly, Sethnakht would later take over KV14 for his own tomb.[121] Setnakhte died after a short reign of approximately two years and was succeeded by his son, Ramesses III, who was already in his forties at the time.[122]

Conspiracy against Ramesses III

[edit]The facts

[edit]

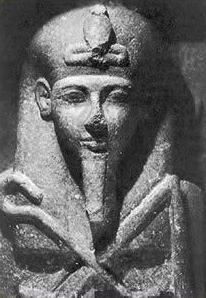

In the 32nd year of Ramesses III's reign, a major coup attempt known as the Harem Conspiracy was launched with the aim of replacing the designated heir, the future Ramesses IV, son of Queen Iset, with Prince Pentawer, son of Queen Tiye, a secondary wife. This event is attested in several ancient documents, most notably the Judicial Papyrus of Turin and the Papyrus Harris. In 2012, medical imaging of Ramesses III’s mummy revealed a deep throat wound, consistent with having been fatally cut, suggesting that the assassination attempt may have succeeded despite official records indicating otherwise.[123][124] The textual sources, which rely heavily on formulaic and euphemistic language, do not clearly acknowledge the king’s murder, likely reflecting an unwillingness to directly record such a regicidal act.[125] The conspiracy involved a wide network of individuals, including many high-ranking members of the royal harem. Armed forces were mobilized to march on the palace, and the plot extended into the provinces, where conspirators recruited agents to foment unrest. Despite the scope of the conspiracy, Queen Tiye’s faction failed to place Prince Pentawer on the throne. Ramesses IV, having secured his succession, convened a tribunal of twelve judges to prosecute the conspirators. Approximately thirty individuals were found guilty, both for their direct involvement and for complicity. Twenty-two were executed, and eleven—including Prince Pentawer—were allowed or compelled to commit suicide.[126] The conspiracy also reflected a broader erosion of central authority. During the trial, three judges and two police officers were found to have accepted bribes—allegedly in the form of promises of illicit harem gatherings—and were punished by the mutilation of their noses and ears.[127] A supernatural dimension also played a role in the conspiracy. The plotters enlisted the services of priests skilled in witchcraft, aiming to weaken the king's spiritual protection. In Egyptian royal ideology, the pharaoh was identified with the sun god Ra, while sedition was equated with the chaos serpent Apep. To undermine this divine order, magical acts were reportedly used to neutralize the palace guards and dismantle the ritual protections surrounding the king.[128]

Ramesses III's throat slit

[edit]

Among the pharaohs suspected of having fallen victim to a conspiracy, Ramesses III is the only one whose mummy has been identified with certainty. His remains were discovered on July 6, 1881, by Gaston Maspero in the royal cache at Deir el-Bahari (TT320), alongside approximately fifty other royal and princely mummies. On June 1, 1886, Maspero unwrapped the mummy to examine it.[129] Now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the body is wrapped in a brownish-orange shroud, secured with simple linen strips. The face is obscured by a dense layer of embalming resin. The king’s head and face appear to have been closely shaved, the eyelids removed, and the eye sockets emptied and filled with linen. The arms are crossed over the chest, with both hands laid flat on the shoulders. The body presents a robust appearance, and the estimated age at death is around sixty-five years.[130][131] Initial X-ray examinations conducted in the 1960s failed to clarify the cause of death. In his 1993 biography of the pharaoh, Egyptologist Pierre Grandet argued that the Harem Conspiracy may not have resulted in the king's death, suggesting instead that the plot served more as a political pretext than a successful regicidal act.[132]

However, a 2012 study led by Zahi Hawass provided strong evidence that Ramesses III died violently.[133] CT images revealed a deep transverse wound to the throat, located just below the larynx. Measuring approximately 70 mm in width, the injury penetrates to the bone between the fifth and seventh cervical vertebrae. All vital soft tissue structures in the area—including the trachea, esophagus, and major blood vessels—were severed, indicating that the wound would have caused almost immediate death. A small amulet in the shape of the wedjat (Eye of Horus), about 15 mm in diameter and made of semi-precious stone, was inserted by embalmers into the lower right edge of the wound—presumably for protective and restorative purposes in the afterlife.[134]

Main conspirators

[edit]

The Harem Conspiracy was fundamentally a succession dispute. Pharaoh Ramesses III had designated his son, Prince Ramesses—born to Queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert—as his heir. At the time of the conspiracy, this prince held the titles of Crown Prince, General, and Royal Scribe. The objective of the conspirators was to overturn the king’s decision and install Prince Pentawer, son of Queen Tiye, as ruler. Preparations for Pentawer’s accession appear to have been advanced, including the drafting of a royal titulary:

Pentawer, the one given this other name. He was brought before the court because he had been in league with Tiye, his mother, when she was plotting with the women of the harem, rebelling against her master. He was brought before the cupbearers for questioning. They found him guilty. He was left in his place. He killed himself.

— "Judicial Papyrus of Turin" (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[135]

According to the court documents, Queen Tiye emerged as the principal instigator of the conspiracy. Utilizing her influence within the harem, she mobilized other women from the institution. The list of convicts includes at least six women, identified as wives of palace porters.[135] The plot also implicated high-ranking harem officials who were charged with the pharaoh’s personal security. These included Panik, director of the king’s chamber, and his deputy Pendouaou, scribe of the same office. Additionally, several administrative officials were convicted of failing to report the conspiracy: the controllers Patchaouemdiimen, Karpous, Khâmopet, Khâemmal, the cupbearer Sethyemperdjehouty, the scribe Pairy, and the harem lieutenant Imenkhâou.[136]

One of the most prominent conspirators was the chamberlain Pabekkamen. He acted as a liaison between the harem and outside supporters, transmitting messages to rally armed resistance against the king:

He was put on trial because he had joined forces with Tiye and the women of the harem. He began to take their messages outside to their mothers and brothers who were there, namely, "Gather people, wage war to rebel against your master!"

— "Judicial Papyrus of Turin" (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[137]

List of conspirators

[edit]Most of the names of the conspirators involved in the plot against Ramesses III were subsequently erased from monuments where they had been inscribed. In judicial records such as the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, the names of the accused were altered into so-called “names of infamy.” These modified names preserved the original phonetic structure but inverted their meaning, effectively transforming them into curses.[138]

The list below is taken from the Papyrus judiciaire:

| Infamous name[n 8] | Meaning | Real name | Meaning | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pebekkamun | The blind servant of Amun | Never revealed[n 9] | Amun's servant | Chef de la chambre.[n 10] |

| Mesedsourê | Ra hates him | Meryrê | Ra's beloved | Cupbearer |

| Panik | The devil | Harem master | ||

| Pendouaou | Scribe to the harem master | |||

| Karpous | Harem controller | |||

| Khâemopet | He who appeared in Opet | Harem controller | ||

| Khâemmal | He who appeared in Mal | Harem controller | ||

| Sethyemperdjehouty | Seth is in Thoth's temple | Harem controller | ||

| Sethyemperamon | Seth is in Amun's temple | Cupbearer | ||

| Oulen | Cupbearer | |||

| Âshahebsed | He who is abundant in the Sed festival | Pebekkamen assistant | ||

| Palik | Cupbearer and scribe | |||

| Libou Yenen | Cupbearer | |||

| Six women | Wives of men at the harem gate | |||

| Payiri, son of Roumâ | Head of treasury | |||

| Binemouaset | Evil in Thebes | Khâemouaset | He who appeared in Thebes | Leader of the Kush troops |

| Payis | The bald | Pahemnétjer | The priest | General |

| Messouy | He who is hated | Scribe in the House of life | ||

| Parâkamenef | Ra blinds him | Parâherounemef | Ra is on his right | Chief ritualist priest |

| Iyry | Ritualistic priest, chief priest of the goddess Sekhmet of Bubastis | |||

| Nebdjéfaou | Cupbearer | |||

| Shâdmesdjer | He whose ear is cut off | Ousekhnemtet | He whose walk is easy | Scribe in the House of life |

| Pentawer | He of the great woman | Never revealed | Son of Ramesses III and Tiye | |

| Tiye | Ramesses III's wife | |||

| Hentouenimen | Mistress of Amun | Cupbearer | ||

| Amunkhâou | Amun's apparition | Harem substitute | ||

| Pairy | Scribe to the King's chamber |

Witchcraft

[edit]During the investigation, the judges concluded that the conspirators had enlisted the assistance of priests skilled in sorcery to further their aims.

The Judicial Papyrus of Turin names several individuals involved in these practices: Parêkamenef, identified as a magician; Messoui and Shâdmesdjer, scribes of the House of Life; and Iyry, director of the pure priests of Sekhmet. The House of Life functioned as a repository of religious and magical texts, while the cult of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet was associated with ritual and incantatory knowledge. According to the Papyrus Rollin, magical texts were illicitly removed from the royal archives, soporific potions were prepared, and wax figurines were crafted to magically disable palace guards:

He began to make magical writings to disorganize and throw into confusion, making some wax gods and some philtres to render human limbs powerless, and handing them over to Pebekkamen(...) and the other great enemies with these words, "Bring them in," and, sure enough, they brought them in. And when he brought them in, the evil deeds he did were done.

— Papyrus Rollin (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[139]

Sentences

[edit]

According to the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, Ramesses III, or more precisely his son Ramesses IV, who invoked his late father's legal authority, established a twelve-member commission to judge the conspirators. This commission included two treasury chiefs, Montouemtaouy and Payefraouy; a senior courtier, the flabellum bearer Kar, five cupbearers, Paybaset, Qédenden, Baâlmaher, Pairousounou, and Djéhoutyrekhnéfer; the royal herald Penrennout, two scribes from the dispatch office, Mây and Parâemheb; and the army standard-bearer Hori. Three members of the commission, bribed during the investigation by General Payis, were also prosecuted. Paybaset was replaced by the cupbearer Méroutousyimen, while the replacements for Mây and Hori remain unknown.[140]

The accused, all referred to as "great enemies," were brought before the "investigation office" and questioned. They quickly confessed to their involvement in the conspiracy.[141]

The judges prepared several lists of defendants. Those on the first list had their names changed, ensuring their eternal infamy. These individuals were executed, but the exact method of execution is not specified in the texts, which simply state, "Their punishment has come to them." Those in the second category, such as Pentawer due to his close ties to the royal family, were condemned to commit suicide. The text notes, "They were left to their own devices in the interrogation room. They took their own lives before any violence was done to them." Corrupt judges who were involved in the conspiracy had their ears and noses mutilated. Paybaset, one of the accused judges, committed suicide following this public punishment.[142][143]

The fate of Queen Tiye and the other women of the harem who were involved in the conspiracy remains unclear, as available sources provide no further details regarding their outcomes.[144]

Notes

[edit]- ^ This myth was recorded during the Ramesside period on a papyrus found at Deir el-Medineh. It is advised to consult the articles: Horus and Set.

- ^ Hatshepsut's presence compensated for the physical weakness of her husband Thutmose II and the youth of Thutmose III; Neferneferuaten compensated for the young age of the weak Tutankhamun and Tausert for that of Siptah.

- ^ The theft of the Osirian relics by Set and their recovery by Anubis-Horus is one of the main themes of the Jumilhac Papyrus (Greco-Roman period). For a translation, see Jacques Vandier, Le Papyrus Jumilhac (in French), Paris, CNRS, 1961.

- ^ a b c The years were counted from each new coronation. As soon as a pharaoh was enthroned, the count started again at year 1.

- ^ Hittite transcription of the Egyptian name Néferkhéperourê the Name of Nesout-bity of king Akhenaton (Gabolde 2015, p. 70).

- ^ These two names mean "The becomings of Ra are alive, He whom the Ka of Ra makes efficient", respectively the name of Nesout-bity and the name of Sa-Ra; two of the five components of the titulature.

- ^ These two names mean "Ra's becomings are alive, Aten's perfection is perfect" (Dessoudeix 2008, pp. 310–311).

- ^ Name inscribed in the Judicial Papyrus of Turin

- ^ While the name itself was never revealed, the meaning itself was. Thus, the name can be reconstructed as either Bakamun or Hemamun.

- ^ i.e. head of the king's "valets de chambre"

References

[edit]- ^ Dictionnaire Le Robert illustré (in French), 1997, pp. 320, 308 et 317.

- ^ Collectif 2004, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramesses III », p. 14.

- ^ Bonnamy & Sadek 2010, pp. 129, p. 533–534 and p. 547–548.

- ^ Vernus 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Obsomer 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Collectif 2004, pp. 12–13, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramesses III »

- ^ Herodotus, Book 2, §.

- ^ Manetho, pp. 53–57.

- ^ Manetho, p. 67.

- ^ Collectif 2004, pp. 5–9, « Assassiner le pharaon ! »

- ^ Collectif 2004, pp. 3–5, Marc Gabolde, « Assassiner le pharaon ! »

- ^ Adler 1982, Adler 2000

- ^ Plutarch (trans. Mario Meunier), Isis et Osiris, Guy Trédaniel éditeur, 2001, p. 57–58.

- ^ Broze, Michèle (1996). Mythe et roman en Égypte ancienne. Les aventures d'Horus et Seth dans le Papyrus Chester Beatty I (in French). Louvain: Peeters..

- ^ Menu 2008, pp. 107–119.

- ^ Jean Leclant (directeur), Dictionnaire de l'Antiquité (in French), Paris, PUF, 2005 (réimpr. 2011), ISBN 9782130589853, p. 1878–1879 : Reine (Égypte).

- ^ Gabolde 2015, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Jan Assmann, Mort et au-delà dans l'Égypte ancienne (in French), Monaco, Le Rocher, 2003, ISBN 2-268-04358-4, p. 80–95.

- ^ Gabolde 2015, pp. 396–401 and passim.

- ^ Obsomer 2005.

- ^ Collectif 2004, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramsès III », p. 11–12.

- ^ Sylvie Cauville, Dendara : Les chapelles osiriennes, Le Caire, IFAO, coll. « Bibliothèque d'étude », 1997 ISBN 2-7247-0203-4. Vol.1 : Transcription et traduction (BiEtud 117), vol. 2 : Commentaire (BiEtud 118).

- ^ Vernus 2001, p. 145.

- ^ Koenig 2001, pp. 296–297.

- ^ Koenig 2001, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Vernus 1993, p. 155.

- ^ Assmann 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b Kanawati 2003.

- ^ a b Husson & Valbelle 1992, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Adolf Erman, Hermann Ranke, La civilisation égyptienne, Tubingen, 1948 (French translation by Payot, 1952, p. 79).

- ^ Bonnamy & Sadek 2010, p. 604

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 14–21.

- ^ Vernus 2001, p. 138 and following.

- ^ Obsomer 2005, p. 53, note 3

- ^ Obsomer 2005, pp. 47 and 52–53

- ^ Christiane Desroches Noblecourt (2000). La femme au temps des pharaons (in French). Paris: Stock/Pernoud. ISBN 978-2-234-05281-9. OCLC 46462982. auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.

- ^ Vernus 2001, p. 167.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, p. 148.

- ^ Aufrère 2010, pp. 95–100.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 14–24.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, p. 89.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, p. 163.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Roccati 1982, pp. 187–197

- ^ Manetho, p. 53.

- ^ Dessoudeix 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Aufrère 2010, pp. 100–102.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 177–182.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Kanawati 2003, p. 185.

- ^ Aufrère 2010, pp. 103–106.

- ^ Aufrère 2010, pp. 95–106.

- ^ Herodotus, Book II. §..

- ^ Clayton 1995, p. 67.

- ^ Aufrère 2010, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Favry 2009, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Menu 2008, p. 118

- ^ Favry 2009, pp. 31–34.