| Choroid | |

|---|---|

Cross-section of human eye, with choroid labeled at top. | |

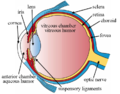

Interior of anterior half of bulb of eye. (Choroid labeled at right, second from the bottom.) | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Short posterior ciliary arteries, long posterior ciliary arteries |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | choroidea |

| MeSH | D002829 |

| TA98 | A15.2.03.002 |

| TA2 | 6774 |

| FMA | 58298 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The choroid, also known as the choroidea or choroid coat, is a part of the uvea, the vascular layer of the eye. It contains connective tissues, and lies between the retina and the sclera. The human choroid is thickest at the far extreme rear of the eye (at 0.2 mm), while in the outlying areas it narrows to 0.1 mm.[1] The choroid provides oxygen and nourishment to the outer layers of the retina. Along with the ciliary body and iris, the choroid forms the uveal tract.

The structure of the choroid is generally divided into four layers (classified in order of furthest away from the retina to closest):

- Haller's layer – outermost layer of the choroid consisting of larger diameter blood vessels;[1]

- Sattler's layer – layer of medium diameter blood vessels;[1]

- Choriocapillaris – layer of capillaries;[1] and

- Bruch's membrane (synonyms: Lamina basalis, Complexus basalis, Lamina vitra) – innermost layer of the choroid.[1]

Blood supply

[edit]The human eye is supplied by two largely distinct vascular systems: the retinal circulation, which nourishes the inner retina, and the uveal circulation (choroidal, ciliary body and iris), which nourishes the uvea and the outer retina (via the choroid). Both systems arise primarily from the ophthalmic artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery.[2]

The uveal circulation is supplied mainly by the posterior ciliary arteries (short and long), which enter the globe independently of the optic nerve. These arteries provide the dominant blood supply to the choroid and contribute importantly to perfusion of the optic nerve head (including the anterior portion of the optic nerve).[3] The retinal circulation derives primarily from the central retinal artery, which travels within the optic nerve and enters the eye at the optic disc. It then branches over the inner retinal surface into arterioles and capillaries supplying the nerve fiber and inner retinal layers.[2]

Retinal arteries behave as functional end-arteries with limited collateralization; consequently, focal obstruction can produce sectoral retinal ischemia. By contrast, the choroid exhibits a segmental vascular organization, and regional perfusion territories supplied by posterior ciliary arteries are clinically relevant because the macula and the anterior optic nerve (structures critical for central vision) depend strongly on choroidal perfusion.[3]

Imaging the choroid and its blood flow

[edit]

Structural features of the choroid can be assessed with optical coherence tomography (OCT), while choroidal vascular contrast is classically obtained with indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), an invasive dye-based method that is relatively robust for deeper choroidal vessels. Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) provides non-invasive motion-contrast maps but can be limited by depth-dependent sensitivity, segmentation/projection artifacts, and reduced sensitivity for very slow flow or deeper large vessels.

Laser-Doppler–based approaches provide an additional, non-invasive route to choroidal flow contrast. In ophthalmology, Laser Doppler holography (LDH) is a full-field, camera-based implementation that uses digital holography and temporal demodulation of reconstructed optical fluctuations to generate Doppler power maps that highlight blood-flow–related signals in retinal and choroidal vessels.[5]

Signal-processing refinements (e.g., spatio-temporal filtering and decomposition methods) have been reported to improve visualization of slower flow components and enhance choroidal vessel contrast in LDH datasets.[4]

Wide-field extensions of Doppler holography have also been described in conference literature for imaging choroidal blood flow over larger posterior-pole regions, with the aim of visualizing major choroidal arteries/veins and outflow patterns (including drainage toward vortex veins) that may be relevant in conditions such as the pachychoroid disease spectrum.[6]

In bony fish

[edit]Teleosts bear a body of capillaries adjacent to the optic nerve called the choroidal gland. Though its function is not known, it is believed to be a supplemental oxygen carrier.[7]

Mechanism

[edit]Melanin, a dark colored pigment, helps the choroid limit uncontrolled reflection within the eye that would potentially result in the perception of confusing images.

In humans and most other primates, melanin occurs throughout the choroid. In albino humans, frequently melanin is absent and vision is low. In many animals, however, the partial absence of melanin contributes to superior night vision. In these animals, melanin is absent from a section of the choroid and within that section a layer of highly reflective tissue, the tapetum lucidum, helps to collect light by reflecting it in a controlled manner. The uncontrolled reflection of light from dark choroid produces the photographic red-eye effect on photos, whereas the controlled reflection of light from the tapetum lucidum produces eyeshine (see Tapetum lucidum).

History

[edit]The choroid was first described by Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE) around 400 BCE, calling it the "chitoon malista somphos" (more spongy tunic [than the sclera]).[8] Democritus likely saw the choroid from dissections of animal eyes.[9]

About 100 years later, Herophilos (c. 335 – 280 BCE) also described the choroid from his dissections on eyes of cadavers.[10][11]

Clinical significance

[edit]Choroid is the most common site for metastasis in the eye due to its extensive vascular supply. The origin of the metastases are usually from breast cancer, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and kidney cancer. Bilateral choroidal metastases are usually due to breast cancer, while unilateral metastasis is due to lung cancer. Choroidal metastases should be differentiated from uveal melanoma, where the latter is a primary tumour arising from the choroid itself.[12]

See also

[edit]Additional images

[edit]-

Schematic cross section of the human eye; choroid is shown in purple.

-

Laser Doppler imaging of retinal and choroidal blood flow

-

Iris, front view

-

The terminal portion of the optic nerve and its entrance into the eyeball, in horizontal section

-

The interior of the posterior half of the left eyeball

-

Structures of the eye labeled

-

This image shows another labeled view of the structures of the eye

-

Calf's eye dissected to expose the choroid: its tapetum lucidum is iridescent blue

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e MRCOphth Sacs questions

- ^ a b Kiel JW. The Ocular Circulation. NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved 2025-12-24.

- ^ a b Hayreh, S. S. (November 1975). "Segmental nature of the choroidal vasculature". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 59 (11): 631–648. doi:10.1136/bjo.59.11.631. PMC 1017426. PMID 812547.

- ^ a b Puyo, Léo; Paques, Michel; Atlan, Michael (2020). "Spatio-temporal filtering in laser Doppler holography for retinal blood flow imaging". Biomedical Optics Express. 11 (6): 3274–3287. doi:10.1364/BOE.392699. PMC 7316027. PMID 32637254.

- ^ Puyo, Léo; Paques, Michel; Fink, Mathias; Sahel, José-Alain; Atlan, Michael (2019). "Choroidal vasculature imaging with laser Doppler holography". Biomedical Optics Express. 10 (2): 995–1012. arXiv:2106.00608. doi:10.1364/BOE.10.000995. PMC 6377881. PMID 30800528.

- ^ Atlan, M. (2025). "Wide-field Doppler Holography of Choroidal Blood Flow". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. Retrieved 2025-12-24.

- ^ "Eye (Vertebrate)" McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, vol. 6, 2007.

- ^ Dolz-Marco, R., Gallego-Pinazo, R., Dansingani, K. K., & Yannuzzi, L. A. (2017). The history of the choroid. In J. Chhablani & J. Ruiz-Medrano (Eds.), Choroidal Disorders (Vol. 1–5, pp. 1–5). Academic Press. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805313-3.00001-6

- ^ Rudolph, Kelli (2012). "Democritus' Ophthalmology". The Classical Quarterly. 62 (2): 496–501. doi:10.1017/S0009838812000109. ISSN 0009-8388.

- ^ Staden, Heinrich von (1989). Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria: Edition, Translation and Essays. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23646-1.

- ^ Reverón, R. (2015). Herophilos, the great anatomist of antiquity. Anatomy, 9(2), 108–111. doi:10.2399/ana.15.003 https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/371071

- ^ Arepalli S, Kaliki S, Shields CL (February 2015). "Choroidal metastases: origin, features, and therapy". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 63 (2): 122–127. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.154380. PMC 4399120. PMID 25827542.

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 08008loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University