Chlorogonium

| Chlorogonium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chlorogonium euchlorum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Chlorophyta |

| Class: | Chlorophyceae |

| Order: | Chlamydomonadales |

| Family: | Haematococcaceae |

| Genus: | Chlorogonium Ehrenberg, 1836 |

| Species | |

Chlorogonium is a genus of green algae in the family Haematococcaceae.[1] It was first described by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1837, with the type species Chlorogonium euchlorum;[2] currently, around 30 species are accepted.[3] They are found in freshwater habitats worldwide.

Description

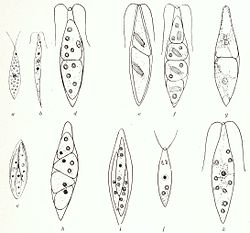

[edit]Chlorogonium consists of spindle-shaped or otherwise elongated cells, with two short, equal flagella at the anterior end of the cell.[3] Each cell contains more than three contractile vacuoles scattered throughout the cytoplasm.[4] There is a single chloroplast in the cell, which is parietal or spiral, filling most of the cell.[5] Pyrenoids are normally present, but in some conditions (such as in photoheterotrophic medium), some species do not produce pyrenoids.[4] At the center of the cell is a single nucleus.[2] The chloroplast generally has a prominent reddish eyespot in the anterior of the cell.[3]

Chlorogonium sensu stricto is characterized by a combination of ultrastructural features, mainly detectable via transmission electron microscopy. Pyrenoids are spherical to nearly angular in shape, and are covered in fragmented starch plates, and have tubular thylakoid membranes penetrating the pyrenoid matrix.[2] The stigma of Chlorogonium is composed of multiple reddish globules, arranged in a single layer.[6]

Reproduction

[edit]Asexual reproduction in Chlorogonium occurs by the formation of zoospores (termed zoosporogenesis). Four or eight zoospores (rarely two) are produced per sporangium (parent cell). During zoospore production, the first division is transverse so that one of the daughter protoplasts retains the original flagellar apparatus and stigma.[5] After the first division, the protoplasts divide once or twice more, eventually becoming elongated.[7] During zoosporogenesis, the sporangium retains flagella and is motile. Zoospores escape through the dissolution of the parental cell wall.[3]

Sexual reproduction has been observed in various Chlorogonium species, and ranges from isogamous to oogamous. The zygotes are spherical with a thick, flattened wall.[3]

Habitat

[edit]Chlorogonium is found in freshwater habitats worldwide,[5] or soil.[3] It most common in bodies of water that are nutrient-poor, dystrophic or filled with decaying leaves. It is most abundant in winter.[8]

Chlorogonium has a notable mutualistic relationship with the American toad, allowing the tadpoles to develop faster when covered with the algae.[9]

Taxonomy and identification

[edit]The taxonomic history of Chlorogonium is very complex. It was first delimited from Chlamydomonas in cell shape, since Chlorogonium generally has elongate, fusiform cells while Chlamydomonas has globose to ellipsoid cells.[10] In 1958, Hanuš Ettl delimited the Chlorogonium based on having multiple scattered contractile vacuoles (while Chlamydomonas has two apical contractile vacuoles). Since young cells of Chlorogonium have only two contractile vacuoles and marine species lack them altogether, this diagnostic character was discarded and most authors considered the mode of cell division as diagnostic for separating the two. In Chlamydomonas, division is longitudinal and each daughter protoplast forms its own flagella, whereas in Chlorogonium division is transverse and one daughter protoplast retains the original flagella.[5]

The most current circumscription of Chlorogonium involves both molecular and morphological data. This has led to the traditional morphologically defined Chlorogonium being recognized as paraphyletic, and the splitting of Chlorogonium into several genera, including Gungnir, Rusalka, Tabris, and Hamakko.[2][6] Morphological features separating these genera include: 1) number of contractile vacuoles and pyrenoids, 2) morphology of the starch plates surrounding the pyrenoids, 3) morphology of the thylakoids penetrating the pyrenoids, and 4) the number of layers of globules forming the stigma.[6]

Within Chlorogonium, species delimitation depends on the number of pyrenoids (and their presence/absence in photoheterotrophic growth conditions), size, shape, and position of the nucleus. However, many species of Chlorogonium have not been investigated with molecular or ultrastructural methods, so their taxonomic statuses are unknown.[4]

| Character | Chlorogonium sensu stricto | Gungnir | Rusalka | Tabris | Hamakko |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of contractile vacuoles | 4+ | 3+ | 2 or 3 | 2 | 4+ |

| Position of contractile vacuoles | Irregularly distributed | Irregularly distributed | Irregularly distributed | Apical | Irregularly distributed |

| Number of pyrenoids | 2 to many | 1 to many | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Starch plates covering pyrenoids | Fragmented | Fragmented | Unfragmented | – | Fragmented |

| Thylakoid membranes penetrating pyrenoids | Present, tubular | – | Present, tubular | – | Present, flattened |

| Position of nucleus | Among pyrenoids | Among pyrenoids | Posterior to pyrenoid | Central | Among pyrenoids |

| Number of layers of globules in stigma | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

See also

[edit]- Chlorococcum amblystomatis, a similar amphibian mutualistic alga

References

[edit]- ^ See the NCBI webpage on Chlorogonium. Data extracted from the "NCBI taxonomy resources". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ a b c d Nakada, Takashi; Nozaki, Hisayoshi; Pröschold, Thomas (2008). "Molecular phylogeny, ultrastructure, and taxonomic revision of Chlorogonium (Chlorophyta): emendation of Chlorogonium and description of Gungnir gen. nov. and Rusalka gen. nov". Journal of Phycology. 44 (3): 751–760. Bibcode:2008JPcgy..44..751N. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00525.x. PMID 27041433.

- ^ a b c d e f Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. "Chlorogonium Ehrenberg, 1836". AlgaeBase. University of Galway. Retrieved 2025-03-26.

- ^ a b c Nakada, Takashi; Soga, Tomoyoshi; Tomita, Masaru; Nozaki, Hisayoshi (2010). "Chlorogonium complexum sp. nov. (Volvocales, Chlorophyceae), and morphological evolution of Chlorogonium". European Journal of Phycology. 45 (1): 97–106. Bibcode:2010EJPhy..45...97N. doi:10.1080/09670260903383263.

- ^ a b c d Bicudo, Carlos E. M.; Menezes, Mariângela (2006). Gêneros de Algas de Águas Continentais do Brasil: chave para identificação e descrições (2 ed.). RiMa Editora. p. 508. ISBN 857656064X.

- ^ a b c d Nakada, Takashi; Nozaki, Hisayoshi (2009). "Taxonomic study of two new genera of fusiform green flagellates, Tabris gen. nov. and Hamakko gen. nov. (Volvocales, Chlorophyceae)". Journal of Phycology. 45 (2): 482–492. Bibcode:2009JPcgy..45..482N. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2009.00652.x. PMID 27033826.

- ^ Nozaki, Hisayoshi; Watanabe, Makoto M.; Aizawa, Kenichi (1995). "Morphology and paedogamous sexual reproduction in Chlorogonium capillatum sp. nov. (Volvocales, Chlorophyta)". Journal of Phycology. 31 (4): 655–663. Bibcode:1995JPcgy..31..655N. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.1995.tb02562.x.

- ^ John, David M.; Whitton, Brian A.; Brook, Alan J. (2021). The Freshwater Algal Flora of the British Isles (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 896. doi:10.1017/CHOL9781108784122. ISBN 978-1-108-78412-2.

- ^ Tumlison, Renn; Trauth, Stanley E. (July 2006). "A novel facultative mutualistic relationship between bufonid tadpoles and flagellated green algae" (PDF). Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 1: 51–55.

- ^ Bourrelly, P. (1966). Les algues d'eau douce. Initiation à la systématique. Tome I: Les Algues vertes. Paris: Boubée & Cie. pp. 1–512.