Carolingian illumination

Carolingian illumination refers to the illuminated manuscripts produced in the Frankish Empire from the late 8th to the late 9th century. While the preceding Merovingian illumination was purely monastic in character, Carolingian illumination originated from the courts of the Frankish kings and the residences of prominent bishops.

The starting point was the court school of Charlemagne at the Aachen Palace, to which the manuscripts of the Ada group are assigned. At the same time, and probably in the same location, there existed the palace school, whose artists were influenced by Byzantine illumination. The codices of this school are also known, after their leading manuscript, as the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels. Despite all stylistic differences, both painting schools share a direct engagement with the formal language of late antique illumination and an effort toward a clarity of page design unprecedented until then. After Charlemagne's death, the center of illumination shifted to Reims, Tours, and Metz. While the court school dominated during Charlemagne's time, the works of the palace school were more strongly received in the later centers of book art.

The heyday of Carolingian illumination ended in the late 9th century. In the late Carolingian period, a Franco-Saxon school developed, which again increasingly adopted forms of the older Insular illumination, before a new era began with Ottonian illumination from the end of the 10th century.

Foundations of Carolingian illumination

[edit]Temporal and geographical framework

[edit]The classification of Carolingian art into an era is inconsistent: sometimes it is considered a distinct art epoch, more often it is summarized with other styles from the 5th to 11th centuries as early medieval art or with Ottonian art as Pre-Romanesque, and occasionally already included in the Romanesque era as early Romanesque.[1] Carolingian art was strongly tied to the respective ruling house and limited to the domain of the Carolingians, thus to the Frankish Empire. Art regions outside this area are not counted as Carolingian art. An exception is the Lombard Kingdom, which Charlemagne was able to conquer in 773/774, but which continued its own cultural traditions that strongly influenced Carolingian art. Conversely, the impulses of the Carolingian Renaissance also affected Italy, especially Rome.

The election of Pepin the Short in 751 as king of the Franks marks the beginning of the Carolingian royal dynasty, but an independent Carolingian art only began under Charlemagne, who was sole ruler of the Frankish Empire from 771 and was crowned emperor in 800. The first luxury manuscript commissioned by Charlemagne between 781 and 783 was the Godescalc Evangelistary. After the death of Louis the Pious, Charlemagne's successor, the empire was divided in 843 by the Treaty of Verdun into the three parts of West, East Francia, and Lotharingia. Lotharingia experienced several further divisions in the following decades, in which some areas fell to West and East Francia, while others became independent kingdoms and duchies in Lorraine, Burgundy, and Italy.

With the death of Louis the Child in 911, the line of the East Frankish Carolingians died out. The new king was Conrad the Younger from the Conradine family. After his death, the nobles of Franconia and the Duchy of Saxony elected Henry I in 919 as East Frankish king. With the transfer of royal dignity to the Saxon Liudolfings, later called Ottonians, the focus of art production also shifted to East Francia, where Ottonian art developed a pronounced independent character. In West Francia, royal dignity passed after the death of Louis the Lazy in 987 to Hugh Capet and thus to the Capetian dynasty. However, the heyday of Carolingian art had already ended throughout the Frankish region by the end of the 9th century; the later sparse and less significant works mostly reverted to older traditions.

Artists and patrons

[edit]

In Merovingian times, only monasteries were responsible for book production, but the Carolingian Renaissance originated from Charlemagne's court. The Godescalc Evangelistary, the Dagulf Psalter, and a plain manuscript[3] attest to Charlemagne as patron in dedication poems and colophons. Under Charlemagne's successors, short-lived workshops were also tied to the courts of the Carolingian emperors and kings or to prominent bishops closely connected to the royal court. Only the monastery of Tours remained productive for decades until its destruction in 853.

Most liturgical books were intended for the royal court. Some of the most precious codices served as gifts of honor; thus, the Dagulf Psalter was planned as a gift from Charlemagne to Pope Hadrian I, although it did not come to a handover due to Hadrian's death. A third group of manuscripts was produced for the empire's most important monasteries to carry the religious and cultural impulses emanating from the imperial court into the empire. Thus, the Saint-Riquier Gospels was intended for Charlemagne's son-in-law Angilbert, the lay abbot of Saint-Riquier, and in 827 Louis the Pious donated a gospel book (Soissons Gospels) from Charlemagne's court school to the church of Saint-Médard in Soissons. Conversely, the Touronian monastery under Abbot Vivian gave Charles the Bald the Vivian Bible in 846, which he probably donated to Metz Cathedral in 869/870.

Few early medieval illuminators are known by name. In an illustrated Terence manuscript, perhaps from Aachen, one of the three painters, Adelricus, hid his name in the gable ornament of a miniature.[4] According to his own statements, the learned Fulda monk Brun Candidus, who had spent some time at the Aachen court school under Einhard, painted the west apse of the Ratgar Basilica consecrated in 819 above the Boniface sarcophagus in Fulda Abbey.[5] This might have given him an important role in the Fulda painting school of the first half of the 9th century. It is hypothetical but not unlikely that he also worked as an illuminator and illustrated the vita of Abbot Eigil written by himself.[6]

More often than the painters, the scribe of a manuscript named himself in a dedication poem or in the colophon. The Godescalc Evangelistary and the Dagulf Psalter received their names after the scribes of the manuscripts. Both describe themselves as chaplains, suggesting that the scriptorium of Charlemagne's court school was connected to the chancery.[7] In the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, the monks Liuthard and Beringer name themselves as scribes.[8] The smaller a scriptorium was and the lower the demand of the illumination, the more likely it is that the scribe also executed the illumination.[9]

The book in Carolingian times and its transmission

[edit]

The books, produced in a labor-intensive process with expensive materials, were an extremely precious luxury item. All Carolingian manuscripts are written on parchment; the cheaper paper only reached Europe in the course of the 13th century. Particularly representative luxury manuscripts, such as the Godescalc Evangelistary, the Soissons Gospels, the Coronation Gospels, the Lorsch Gospels, and the Bible of St. Paul were written with gold and silver ink on purple-dyed parchment. Their book covers were decorated with ivory carving panels framed by goldsmith works studded with gems. In the miniatures, gouache painting dominated; rarer was the – usually colored – pen drawing.

Around 8000 manuscripts from the 8th and 9th centuries survive.[10] How great the book losses are due to Viking invasions, wars, iconoclastic storms, fires, and other violent causes, due to disregard or reuse of parchment as raw material, is hardly estimable. Surviving library catalogs provide information on the extent of some of the largest libraries. Thus, the book stock of St. Gallen Monastery rose in Carolingian times from 284 to 428,[11] Lorsch Abbey owned 590 in the 9th century,[12] and the monastery library in Murbach 335[11] manuscripts. Wills provide an idea of the extent of private libraries. The 200 codices that Angilbert bequeathed to his monastery Saint-Riquier[13] and among which was also the Saint-Riquier Gospels, were probably one of the largest libraries. Eccard of Mâcon bequeathed about twenty books to his heirs.[13] How large Charlemagne's library was, which was sold after his death according to his testamentary provisions, is unknown. In the Aachen library, all essential available works and numerous illustrated manuscripts were gathered, including many Roman, Greek, and Byzantine books.[14]

Most manuscripts were not illuminated at all, a small part modestly. As a rule, only the few major works of Carolingian illumination enter art historical literature. Valuable luxury manuscripts – especially if they were liturgical books – always enjoyed preferential treatment. The most exclusive codices were not utility literature but belonged as liturgical equipment to the church treasure or served primarily representative purposes, as the often minimal signs of use suggest.[15] Illustrations on the very durable parchment are also well protected from external influences in a closed book, and the codices were long stored not in open shelves but in chests, rarely in lockable cabinets. Thus, the illustrated manuscripts from Carolingian times have survived in relatively large numbers, and many miniatures have survived the past about twelve centuries in very good condition. Most surviving illustrated manuscripts are completely preserved; fragmentary transmission is rare. That nevertheless a considerable number of lost illuminated manuscripts must be reckoned with is proven by later illustrations that are aftereffects of non-preserved image templates.[16] In some cases, no longer existing illuminated codices are attested: thus a “golden psalter” of Queen Hildegard from the early days of Carolingian illumination.[17]

The easily meltable golden book covers, on the other hand, have withstood the grasp of later times only in a few cases. More often, the ivory panels of the bindings are preserved, but in no case in connection with the codex they originally adorned. The five panels of the Lorsch Gospels are today in the Vatican Museums. At least the lower ivory panel is not a Carolingian work but a late antique original, as an inscription on its back proves.[18] The only securely datable ivory panels are those of the Dagulf Psalter, which are exactly described in its dedication poem and thus could be identified with two panels in the Paris Louvre.[19] Illumination was in close interaction with ivory carving. The small-format, easily transportable artworks played an important role as mediators of ancient and Byzantine art. In contrast, only a few fragments of Carolingian large sculpture have survived, while works of goldsmithing are better preserved. In connection with illumination, the book cover of the Codex aureus of St. Emmeram from the court school of Charles the Bald is particularly interesting.

Due to the relatively good transmission situation, Carolingian illumination and miniature have greater significance for art history than those of other epochs, since all other art genres from Carolingian times are extremely poorly preserved. This applies especially to monumental fresco painting, which, like in the later Ottonian and Romanesque periods, was the leading genre of Carolingian painting. It must be assumed that every church as well as the palaces were painted with frescoes;[1] the minimal preserved remains, however, no longer allow a vivid idea of the former splendor of images. Mosaics in ancient tradition also played a role; thus, the palatine chapel in Aachen was decorated with a splendid dome mosaic.[1]

Precursors and influences

[edit]Merovingian illumination

[edit]

The Carolingian Renaissance formed in a pronounced “cultural vacuum”,[20] its center became Charlemagne's residence Aachen. Merovingian illumination, named after the Merovingian ruling dynasty preceding the Carolingians in the Frankish Empire, remained purely ornamental. The initials constructed with ruler and compass as well as title pages with arcades and inserted cross are almost the only form of illustration. From the 8th century, increasingly zoomorphic ornaments appeared, which became so dominant that in manuscripts from the women's abbey Chelles, entire lines consist exclusively of letters formed from animals. In contrast to the contemporary Insular illumination with proliferating ornamentation, Merovingian strove for a clear order of the page. One of the oldest and most productive scriptoria was that of the abbey Luxeuil founded in 590 by the Irish monk Columbanus, which was destroyed in 732. The abbey Corbie founded in 662 developed a pronounced own illustration style, Chelles and Laon were further centers of Merovingian book illustration. From the mid-8th century, this was strongly influenced by Insular illumination. A Gospel book from Echternach proves that in this monastery there was collaboration between Irish and Merovingian scribes and illuminators.

Insular illumination

[edit]

Until the Carolingian Renaissance, the British Isles were the refuge of Roman-early Christian tradition, which, however, through mixing with Celtic and Germanic elements, had produced an independent Insular style, whose sometimes violently expressive, ornament-preferring, and strictly two-dimensional character ultimately stood in antinaturalism directly opposed to ancient formal language.[21] Only exceptionally did Insular illuminations preserve classical design elements, such as the Codex Amiatinus (southern England, around 700) and the Codex Aureus of Stockholm (Canterbury, mid-8th century).

Through the Hiberno-Scottish mission emanating from Ireland and southern England, the European continent was strongly shaped by Insular monastery culture. In all of France, Germany, and Italy, Irish monks founded monasteries in the 6th and 7th centuries, the “Schottenklöster”. These included Annegray, Luxeuil, St. Gallen, Fulda, Würzburg, Sankt Emmeram in Regensburg, Trier, Echternach, and Bobbio. In the 8th and 9th centuries, a second Anglo-Saxon mission wave followed. Through this path, numerous illuminated manuscripts reached the continent, which had a strong influence on the respective regional formal languages, especially in script and ornamentation. While in Ireland and England, due to the Viking attacks from the end of the 8th century, book production largely came to a standstill, on the continent, illuminations in Insular tradition were still produced for some decades. Alongside the works of the Carolingian court schools, this branch of tradition remained alive and shaped the Franco-Saxon school in the second half of the 9th century, but the court schools also adopted elements of Insular illumination, especially the initial page.

Reception of antiquity

[edit]

The recourse to antiquity was the main characteristic of Carolingian art as such. The programmatic adaptation of ancient art was consistently oriented toward the late Roman emperorship and fit into the basic idea known as renovatio imperii romani, to claim the heritage of the Roman Empire in all areas. The arts fit as an elementary part into the intellectual current of the Carolingian Renaissance.

Of great importance for the reception of ancient art was the study of original works, which were still numerous in Rome. For the artists and scholars of the north who did not know Italy from personal observation, works of late antique illumination played an essential mediating role, for besides miniature, only the book reached directly into the workshops and libraries north of the Alps. The scriptorium in Tours is known to have used ancient originals as models. Thus, figures from the Vatican Virgil, which was in the possession of the Touronian library, were traced and appear in the Bibles.[22] Other ancient manuscripts in the possession of the significant library were the Cotton Genesis and the Leo Bible from the 5th century.[23] Many lost illustrated books of late antiquity are today only accessible through Carolingian copies.

Byzantium

[edit]Besides the original works, Byzantine illumination mediated the ancient heritage, which had been productively continued there in largely unbroken tradition. However, the Byzantine iconoclasm, which banned the religious cult of images between 726 and 843 and triggered a wave of image destruction, meant an important break in the continuity of transmission. With the Exarchate of Ravenna, Byzantium still had an important bridgehead in the west until the 8th century. Artists who had fled from Byzantium due to persecution for the image ban also promoted Roman art.[20] From Byzantine-influenced Italy, Charlemagne drew artists to his court who created the works of the palace school.

Italy

[edit]Italy was significant not only as a mediator of classical and Byzantine art. Rome experienced a particularly pronounced renovatio movement, which was related to the Carolingian Renaissance in the Frankish Empire.[24] Through its role as protectorate of the papacy, the Frankish Empire was closely connected to Rome, which, despite its decline since the Migration Period, was still considered caput mundi, the head of the world. In the years 774, 780/781, and on the occasion of his imperial coronation in 800, Charlemagne himself stayed in Rome for longer periods.

Since he had conquered the Lombard Kingdom in 774, rich cultural streams flowed from there to the north. The illuminations of Charlemagne's court school show similarities with Lombard works, and already the idea, new for Frankish kings, of commissioning luxury manuscripts could go back to models at the Lombard court in Pavia.[25]

Development of Carolingian illumination

[edit]There is no uniform Carolingian style. Instead, three branches have emerged, going back to very different painting schools. Two courtly painting schools were active at Charlemagne's Aachen court around 800 and are referred to as “court school” or “palace school”. On this basis, pronounced workshop styles developed, especially in Reims, Metz, and Tours, which rarely remained productive for longer than two decades and were strongly dependent on the respective tradition of the scriptorium, the extent and quality of the available library, as well as the personality of the patron. A third style, largely independent of the court schools, continued Insular illumination as the Franco-Saxon school and dominated illumination from the end of the 9th century.

Both courtly painting schools share the direct engagement with the formal language of late antiquity as well as the effort toward a clarity of page design unprecedented until then. While Insular and Merovingian illumination were characterized by abstract interlace patterns and schematized animal ornaments, Carolingian art again adopted classical ornaments with the egg-and-dart, the palmette, the vine scroll, and the acanthus. In figural painting, the artists strove for a comprehensible representation of anatomy and physiology, the three-dimensionality of bodies and spaces, as well as light effects on surfaces. Especially the element of plausibility overcame the previous schools, whose descriptive representations, unlike their abstract images, were “unsatisfactory, not to say ridiculous”.[26]

The clear order of illumination was only part of the Carolingian reformation of book affairs. It formed a conceptual unit with the careful redaction of standard editions of biblical books as well as the development of a uniform, clear script, the Carolingian minuscule. In addition – especially as decoration and structuring element – the entire canon of ancient scripts appeared, such as the uncial and the half-uncial.

Types of illustrated books and iconographic motifs

[edit]

The book gained special significance through the connection of text and image as an instrument for spreading the renovatio idea in the empire. At the center of the reform efforts for a uniform regulation of the liturgy stood the Evangeliary. The Psalter was the first type of prayer book. From about the middle of the 9th century, the spectrum of books to be illustrated expanded to include the full Bible and the sacramentary. The execution of these liturgical books was expressly entrusted in the Admonitio generalis of 789 only to experienced hands, perfectae aetatis homines.[27]

The main decoration of the Evangeliaries were depictions of the four Evangelists. The Maiestas Domini, the image of the enthroned Christ, appears rarely at first, Mary images and depictions of other saints almost not at all during the entire Carolingian epoch. In 794, the Synod of Frankfurt had dealt with the Byzantine iconoclasm and banned veneration of images, but assigned the task of instruction and teaching to painting. The Libri Carolini, whose author was probably Theodulf of Orléans, are considered the official statement of the circle around Charlemagne in this sense.[28] An early Maiestas Domini depiction appears in 781/783, thus a few years before the fixing of this position, in the Godescalc Evangelistary. After a Frankish synod loosened the provisions in 825, the scale of depictable themes expanded especially in the schools of Metz and Tours.[29] From the mid-9th century, the Maiestas Domini motif was a central motif especially of the Touronian Evangeliaries and Bibles[30] and now belonged together with the Evangelist portraits to a fixed iconological illustration cycle. In the Godescalc Evangelistary, the motif of the Fountain of Life appears for the first time, which is repeated in the Soissons Gospels. Another new motif was the Adoration of the Lamb. Canon tables with arcade framings belong to the fixed inventory of the Evangeliaries. Characteristic of Charlemagne's court school were throne architectures, which are absent in the works of the palace school as well as the schools of Reims and Tours. From Insular illumination, the illuminators adopted the initial page.

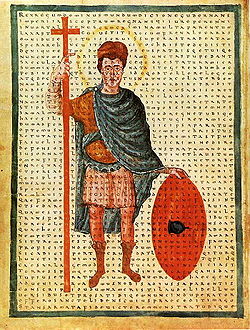

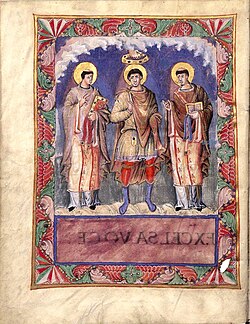

A central motif from the time of Louis the Pious was the ruler portrait, which appears especially in manuscripts from Tours. In terms of the programmatic appropriation of the Roman heritage in the sense of a renewal and thus the legitimation of Carolingian rule, this motif had special significance. From the comparison of the images with descriptions in contemporary literature, such as Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni and Thegan's Gesta Hludowici, it can be concluded that these are typological portraits in the spirit and after the model of Roman ruler portraits, enriched with naturalistic-portrait elements.[31] The sacral significance of the imperial office is thematized in almost all Carolingian ruler portraits, which accordingly appear especially in liturgical books. Often the Hand of God appears above the rulers. The sacral connotation is most clearly expressed in a depiction of the nimbed, cross-bearing Louis the Pious as illustration of De laudibus sanctae crucis by Rabanus Maurus.[2]

Besides the liturgical, relatively few secular books were illustrated, among which copies of late antique constellation cycles play a special role. Among these stands out an Aratea manuscript from around 830–840, which was copied several times later. The Bern Physiologus (Reims, around 825–850) is the most significant from a series of illustrated manuscripts of the natural history of the Physiologus. An important textbook for the Middle Ages was Boethius’ work De institutione arithmetica libri II, which was illuminated in Tours in the 840s for Charles the Bald.[32] Among the illustrated works of classical literature are especially manuscripts with comedies of Terence, which around 825 in Lotharingia[4] or in the second half of the 9th century in Reims,[33] as well as a manuscript with poems of Prudentius,[34] which possibly comes from the Reichenau Abbey and was illustrated in the last third of the 9th century.

Everyday scenes are found particularly numerous embedded in Psalm illustrations, such as in the Utrecht, the Stuttgart Psalter, and the Golden Psalter of St. Gallen. Other books like a martyrology of Wandalbert of Prüm[35] (Reichenau, third quarter of the 9th century) occasionally contain calendar pictures with peasant activities over the course of the year, dedication miniatures or depictions of writing monks. Historiography as well as legal texts played no role yet for Carolingian illumination. Vernacular literature was codified only in a few exceptions and by no means enjoyed the appreciation that would have been a prerequisite for illumination. This applies even to demanding Bible poetry like Otfrid's Gospel book.

Illumination in the time of Charlemagne

[edit]

The monastic and strongly Insular-influenced Merovingian book culture initially continued unaffected by the change of the Frankish ruling dynasty. This changed abruptly at the end of the 8th century when Charlemagne (reign 768–814) gathered the most significant figures of his time at his court in Aachen to reform the entire intellectual life. After his Italy trip in 780/781, Charlemagne appointed the Briton Alcuin as head of the court school, whom he had met in Parma and who had previously led the school of York. Other scholars at Charlemagne's court were Peter the Deacon or Theodulf of Orléans, who also taught Charlemagne's children as well as young nobles at court. Many of these scholars were sent after some years as abbots or bishops to important places in the Frankish Empire, for with the renewal idea was connected the will that the intellectual achievements of the court should radiate to the entire giant empire. Thus Theodulf became bishop of Orléans, Alcuin in 796 appointed bishop of Tours. For him, Einhard took over the leadership of the court school.

Around 800, two very different groups of luxury manuscripts for liturgical use in the great monasteries and at the episcopal sees were created at Charlemagne's court. The two manuscript groups are referred to either after outstanding works as “Ada group” or “group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels” or as “court school” or “palace school of Charlemagne”. The illustrated texts of both workshop groups are in the closest connection, while the illustrations themselves have no stylistic points of contact. The relationship of the two painting schools to each other has therefore long been disputed. For the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels, a different patron than Charlemagne has been repeatedly discussed,[22] but the evidence speaks for a localization at the Aachen court.[36]

The Ada group or court school

[edit]

The first luxury manuscript that Charlemagne commissioned between 781 and 783, thus immediately after his Rome trip, was the Godescalc Evangelistary named after its scribe. Possibly this work was not yet created in Aachen but in the royal palace Worms.[17]

The large initial page, ornamental letters, and part of the ornamentation come from the Insular, but nothing recalls Merovingian illumination. The new in the illumination are the decorative elements taken from antiquity, the plastic-figural motifs, as well as the used script. The full-page miniatures – the enthroned Christ, the four Evangelists, as well as the Fountain of Life – strive for real corporeality and a logical connection to the depicted space and thus became style-forming for the following works of the court school. The text was written with golden and silver ink on purple-dyed parchment.

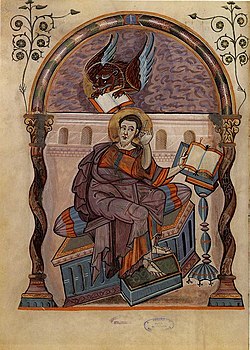

The manuscripts of the Ada group from the court school, which can certainly be localized in Aachen, share the conscious engagement with the ancient heritage as well as a consistent image program. They probably oriented themselves mainly on late antique models from Ravenna.[37] Besides splendid arcade and Insular-influenced initial decoration pages imitating architectural motifs or gem-studded picture frames belong large-area Evangelist portraits to the equipment, which vary a basic type many times since the Ada Gospels. The figures with clearly contoured internal drawing are given corporeality for the first time since Roman times by swelling, rich garments, three-dimensionality to the space.[38] The images share a certain horror vacui, the fear of emptiness, so expansive throne landscapes fill the pages with the Evangelist portraits.

Around 790, the first part of the Ada Gospels and a Gospels of Saint-Martin-des-Champs were created. It was followed by the Dagulf Psalter, also named after its scribe, written before 795, which according to the dedication poem was commissioned by Charlemagne himself and was intended as a gift for Pope Hadrian I. Still at the end of the 8th century, the Saint-Riquier Gospels and the Harley Gospels in London are to be dated, around 800 the Soissons Gospels as well as the second part of the Ada Gospels and around 810 the Lorsch Gospels. A fragment of a Gospel book in London[39] concludes the series of illustrated manuscripts from the court school. After Charlemagne's death, it apparently dissolved.[28] As determining as its influence was until then, it seems to have left only few traces for the illumination of the following decades.[28] Aftereffects can be detected in Fulda, Mainz, Salzburg, and in the vicinity of Saint-Denis as well as some northeast Frankish scriptoria.[16]

The group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels or palace school

[edit]

A second manuscript group, probably also to be localized in Aachen,[29] but clearly differing from the illustrations of the court school, stands rather in Hellenistic-Byzantine tradition and groups around the Coronation Gospels, which was produced around 800. According to legend, Otto III found the luxury manuscript when opening Charlemagne's grave in 1000. Since then, the also artistically most significant manuscript of this workshop group was part of the Imperial Regalia, and the German kings took the coronation oath on the Evangeliary. In distinction to the court school, the manuscripts of the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels are attributed to a palace school of Charlemagne. It includes four further manuscripts: The Treasury Gospels, the Xanten Gospels, and a Gospel book from Aachen,[40] all to be dated to the early 9th century.

The manuscripts of the group of the Vienna Coronation Gospels have no predecessors in northern Europe in their time. The effortless virtuosity with which the late antique forms were realized must have been learned by the artists in Byzantium, perhaps also in Italy.[29] In comparison with the Ada group of the court school, they especially lack the horror vacui. The figures of the Evangelists, moved by dynamic swings, are depicted in the posture of ancient philosophers. Their powerfully modeled bodies, airy and light-flooded landscapes, as well as mythological personifications and other classical motifs give the works of this group the atmospheric and illusionistic character of Hellenistic painting.

During Charlemagne's lifetime, the palace school seems to have been a relatively isolated special case of illumination, which stood in the shadow of the court school.[29] After Charlemagne's death, however, it was this painting school that exerted much stronger influence on Carolingian illumination than the Ada group.

Illumination in the time of Louis the Pious

[edit]

After Charlemagne's death, court art shifted under Louis the Pious (reign 814–840) to Reims, where in the 820s and early 830s under Archbishop Ebbo especially the dynamically moved image conception of the Vienna Coronation Gospels was received. Ebbo was considered before his appointment to Reims in 816 as “librarian of the Aachen court”[41] and brought the heritage of the Carolingian Renaissance with him. The Reims artists rooted in another painting tradition transformed the already lively style of the palace school into an expressive line style with nervously swirling line guidance and ecstatically excited figures. The sketchy images with dense, jagged stroke guidance show the greatest possible distance to the calm image structure of the Aachen court school. In Reims and in the nearby Hautvillers Abbey were created as main works around 825 the Ebbo Gospels and perhaps by the same artist the extraordinary Utrecht Psalter illustrated with uncolored pen drawings as well as the Bern Physiologus and the Blois Gospels.[42] The 166 representations of the Utrecht Psalter show besides paraphrasing illustrations of the Psalms numerous everyday scenes.

Besides the imperial court, the great imperial abbeys and bishop's residences with powerful scriptoria gradually came to the fore again. From 796 until his death in 804, Alcuin, previously religious and cultural advisor to Charlemagne, was delegated as abbot to St. Martin in Tours to carry the renewal idea to this important city of the Frankish Empire. Under the image-critical Alcuin, the scriptorium flourished, but illustrations were initially absent from the manuscripts, so that the so-called Alcuin Bibles were only decorated with remarkable figural illumination in the time of his successors.

Under Archbishop Drogo of Metz (823–855), an illegitimate son of Charlemagne, the Metz school tied in with Charlemagne's court school. The Drogo Sacramentary created around 842 is the main work of this atelier, from whose works among others an astronomical-computistic textbook[43] is preserved. The original achievement of the Metz school is the historiated initial, that is, the ornamental letter populated with scenic representations, which was to become the most characteristic element of all medieval illumination.

The court schools of Charles the Bald and Emperor Lothar

[edit]

After the division of the Frankish Empire in the Treaty of Verdun in 843, Carolingian illumination reached its highest bloom in the circle of the now West Frankish king Charles the Bald (reign 840–877, emperor 875–877). Head of Charles's court school, sometimes referred to after the significance of Corbie Abbey for the book art of the epoch as school of Corbie, was John Scotus Eriugena, who as art theorist formulated the aesthetic conception of the entire Middle Ages in a groundbreaking way. A leading role for illumination was taken over by the monastery in Tours under the abbots Adalard (834–843) and Vivian (844–851). From about 840, huge illustrated full Bibles were created, which were intended among other things for monastery foundations, including around 840 the Moutier-Grandval Bible and 846 the Vivian Bible. After the peace agreement of Charles with his brother in 849, the monastery was also in close connection with Emperor Lothar I. With the Lothar Gospels, the school of Tours reached its artistic peak. The Tours workshop stood under immediate and strong influence of the Reims school. The scriptorium of Tours was the only one of the entire Carolingian period that remained productive over several generations, but with the destruction by the Normans in 853, its heyday ended abruptly.

If Tours is to be regarded until then as the location of Charles the Bald's court school, then after the destruction of the monastery probably St. Denis near Paris took over this role,[30] where Charles the Bald became lay abbot in 867. From the time after 850 come some particularly richly decorated manuscripts, including a Psalter (after 869) and a sacramentary fragment. The most splendid manuscripts are the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which was illuminated around 870 on behalf of Charles the Bald, and the Bible of St. Paul written at about the same time with gold ink on purple ground with 24 full-page miniatures and 36 initial decoration pages.

The court school of Emperor Lothar was probably located in Aachen.[44] It took up the style of Charlemagne's palace school again and apparently had close contact with the Reims scriptorium, as the Kleve Gospels shows.

Illumination outside the court schools

[edit]

While the most significant book illustrations were created at the Carolingian courts or in abbeys and episcopal residences closely connected to the court, many monastic ateliers cultivated their own traditions. Some of these were shaped by Insular illumination or continued the Merovingian style. In some cases, independent achievements occurred. The book art of Corbie Monastery had already played an important role for illumination in Merovingian times, and the script of the monastery is considered the basis of the Carolingian minuscule. Remarkable is a Psalter from Corbie[45] (around 800), whose figure initials cannot be connected either with courtly Carolingian or with Insular illumination and which points ahead to Romanesque illumination. Already around 788, the richly equipped Montpellier Psalter was created in Mondsee Abbey, which was probably intended for a member of the Bavarian ducal family.

A special case are the Bibles and Evangeliaries written in the first quarter of the 9th century under Bishop Theodulf in Orléans. Theodulf was next to Alcuin the leading theologian at Charlemagne's court and probably author of the Libri Carolini. Even more than Alcuin, he was critical of images, and so the codices from his scriptorium[46] are indeed elaborately designed purple-dyed and written with gold and silver ink luxury manuscripts, but their painterly decoration is limited to canon tables. Also a Gospel book from the monastery Fleury,[47] which belonged to the diocese of Orléans, contains besides 15 canon tables only one miniature with the Evangelist symbols.

The Fulda painting school was apparently one of the few in the succession of the Aachen court school.[28] This dependence is clearly evident in the Fulda Gospels in Würzburg[48] from the mid-9th century. Beyond that, however, it also borrowed from Greek models, so the nimbed figure of Louis the Pious in a copy of de laudibus sanctae crucis[2] by Rabanus Maurus is entirely enveloped by the text as a picture poem and thus refers to depictions of Constantine the Great.[49] Rabanus Maurus, a student of Alcuin, was abbot of Fulda Monastery until 842.

The transition to Ottonian art

[edit]

After the death of Charles the Bald in 877, a barren period of about a hundred years began for the visual arts. Only in the monasteries did illumination – mostly at a comparatively modest level – continue, the courts of the Carolingian rulers no longer played a role. With the shift in power relations, the East Frankish monasteries gained increasing importance. Especially the initial style of St. Gallen Monastery, but also the illuminations of the monasteries Fulda and Corvey took on a mediating role to Ottonian illumination. Further monastic centers of the East Frankish Empire were the scriptoria in Lorsch, Regensburg, Würzburg, Mondsee, Reichenau, Mainz, and Salzburg. Especially the monasteries near the Alps were in close artistic exchange with Upper Italy.

In today's northern France, the Franco-Saxon school had developed, intensified since the second half of the 9th century, whose book decoration was largely limited to ornamentation and again drew on Insular illumination. Saint-Amand Monastery had a pioneering role, besides which the abbeys St. Vaast in Arras, Saint-Omer, and St. Bertin appeared. An early example of this style is a Psalter written for Louis the German in the second quarter of the 9th century from Saint-Omer. The most significant manuscript of the Franco-Saxon school is the Second Bible of Charles the Bald, which was created between 871 and 873 in Saint-Amand Monastery.

Only around 970 did a new, completely different style set in in illumination under the changed conditions of the now Saxon ruling house.[51] Ottonian art is also called “Ottonian Renaissance” in analogy to Carolingian, but it hardly drew directly on ancient models. Rather, influenced by Byzantine art, it referred to Carolingian illumination. In doing so, Ottonian illumination developed a pronounced own, homogeneous formal language, but at its beginning stood adaptations of Carolingian works. Thus the Maiestas Domini of the Lorsch Gospels was exactly, though reduced, copied in the late 10th century on Reichenau in the Petershausen Sacramentary and in the Gero Codex.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kluckert, Ehrenfried (2007). Rolf Toman (ed.). Romanesque Painting [Romanik. Architektur, Skulptur, Malerei] (in German). o.O.: Tandem Verlag. p. 383.

- ^ a b c d Cod. 652 (in German). Vienna: Austrian National Library. Literature: Mütherich/Gaede, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Rome, Vallicelliana.

- ^ a b Rome, Vaticana, Vat. lat. 3868. Literature: 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit, Volume 2, pp. 719–722.

- ^ Vita Aegil II c. 17, 131–137

- ^ Christine Ineichen-Eder, Künstlerische und literarische Tätigkeit des Candidus-Brun von Fulda. In: Fuldaer Geschichtsblätter 56, 1980, pp. 201–217, here p. 201; pp. 209f.; cf. the critical edition by Gereon Becht-Jördens, pp. XXIX-XL; the illustrations ibid. p. 31; p. 39; p. 42. The only manuscript, after which the Jesuit Christoph Brouwer edited the text in his Sidera illustrium et sanctorum virorum published in Mainz in 1616 and from which he published copperplate reproductions of three illustrations in his Antiquitatum Fuldensium libri IV published in Antwerp in 1612, was probably lost during the Thirty Years' War with the Fulda library.

- ^ Fillitz, p. 25.

- ^ Walther/Wolf, p. 98.

- ^ Jakobi-Mirwald, pp. 149f.

- ^ Pierre Riché: Die Welt der Karolinger, p. 249. Reclam, Stuttgart 1981. The number is based on the state of knowledge in the 1960s.

- ^ a b Pierre Riché: Die Welt der Karolinger, pp. 251ff. Reclam, Stuttgart 1981.

- ^ Lexikon der Buchkunst und der Bibliophilie, ed. by Karl Klaus Walther, p. 47. Weltbild, Munich 1995.

- ^ a b Pierre Riché: Die Karolinger, p. 393. dtv, Munich 1991.

- ^ Grimme, p. 34.

- ^ Jakobi-Mirwald, pp. 215ff.

- ^ a b Mütherich 1999, p. 564.

- ^ a b Mütherich 1999, p. 561.

- ^ Bering, pp. 219f.

- ^ Magnus Backes, Regine Dölling: Die Geburt Europas, pp. 96ff. Naturalis Verlag, Munich n.d.

- ^ a b Erwin Panofsky: Die Renaissancen der europäischen Kunst, p. 58. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: Die Renaissancen der europäischen Kunst, p. 60. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ^ a b Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 239.

- ^ Bering, p. 137.

- ^ Bering, pp. 110f.

- ^ John Mitchell: Karl der Große, Rom und das Vermächtnis der Langobarden, in: 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit, Volume 2, p. 104.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: Die Renaissancen der europäischen Kunst, p. 62. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990.

- ^ Capitularia regum Francorum 1. Ed. by Georg Heinrich Pertz. Monumenta Germaniae Historica 3, Leges in folio 1. Hanover 1835, unchanged reprint Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7772-6505-5, pp. 53–62 No. 22. [Also accessible as Online Edition

- ^ a b c d Holländer, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d Holländer, p. 249.

- ^ a b Holländer, p. 253.

- ^ Laudage, pp. 92f.

- ^ Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, Msc.Class.5. Literature: 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit, Volume 2, pp. 725–727.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 7899. Literature: Mütherich/Gaehde, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 264. Literature: Mütherich/Gaehde, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Rome, Vaticana, Reg. lat. 438. Literature: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Liturgie und Andacht im Mittelalter, pp. 82–83. Published by the Archdiocesan Diocesan Museum Cologne. Belser, Stuttgart and Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7630-5780-3

- ^ Thus among others Fillitz, p. 22.

- ^ Jakobi-Mirwald, p. 238.

- ^ Lexikon des Mittelalters, col. 842.

- ^ London, British Library, Cotton Clausius B. V.

- ^ Brescia, Biblioteca Queriniana, Ms. E. II. 9.

- ^ Grimme, p. 45.

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 265.

- ^ Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, Cod. 3307. Literature: Mütherich/Gaehde, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bering, p. 134.

- ^ Amiens, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 18. Literature: Fillitz, p. 34; 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit, Volume 2, pp. 811–812.

- ^ Paris Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 9380 (so-called Theodulf Bible from Orléans); Manuscript in Le Puy, Treasury; Gospel book from Tours, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 22; Gospel book from Fleury, Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 348. Literature: Bering, pp. 135f.

- ^ Bern, Burgerbibliothek, Cod. 348. Literature: Mütherich/Gaehde, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Würzburg, University Library, Mp. theol. fol. 66

- ^ Grimme, p. 53.

- ^ Lorsch Gospels.

- ^ Erwin Panofsky: Die Renaissancen der europäischen Kunst. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1990, pp. 64–65.

External links

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Kunibert Bering: Kunst des frühen Mittelalters (Kunst-Epochen, Volume 2). Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-018169-0; pp. 248–263

- Bernhard Bischoff: Katalog der festländischen Handschriften des neunten Jahrhunderts (mit Ausnahme der wisigotischen)

- Part 1: Aachen – Lambach. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03196-4

- Part 2: Laon – Paderborn. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-447-04750-X

- Bernhard Bischoff: Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne, translated and edited by Michael Gorman (= Cambridge Studies in Palaeography and Codicology 1), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, ISBN 0-521-38346-3

- Peter van den Brink, Sarvenaz Ayooghi (eds.): Karl der Große – Charlemagne. Karls Kunst. Catalog of the special exhibition Karls Kunst from June 20 to September 21, 2014 at the Centre Charlemagne, Aachen. Sandstein, Dresden 2014, ISBN 978-3-95498-093-2 (on illumination passim)

- Hermann Fillitz: Propyläen-Kunstgeschichte, Volume 5: Das Mittelalter 1. Propyläen-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-549-05105-0

- Ernst Günther Grimme: Die Geschichte der abendländischen Buchmalerei. DuMont, Cologne 3rd edition 1988, ISBN 3-7701-1076-5 (chapter Karolingische Renaissance, pp. 34–57).

- Hans Holländer: Die Entstehung Europas. In: Belser Stilgeschichte. Study edition, Volume 2, edited by Christoph Wetzel, Belser, Stuttgart 1993, pp. 153–384 (on illumination pp. 241–255).

- Christine Jakobi-Mirwald: Das mittelalterliche Buch. Funktion und Ausstattung. Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-018315-4 (chapter Karolinger und Ottonen, pp. 237–249).

- Wilhelm Koehler: Die karolingischen Miniaturen. Three volumes, Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft (Denkmäler deutscher Kunst), formerly Verlag Bruno Cassirer, Berlin 1930–1960, continued by Florentine Mütherich, Volumes 4–8, Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, later Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 1971–2013

- Johannes Laudage, Lars Hageneier, Yvonne Leiverkus: Die Zeit der Karolinger. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-89678-556-7

- Lexikon des Mittelalters: Buchmalerei. 1983, Volume 2, cols. 837–893 (contributions by K. Bierbrauer, Ø. Hjort, O. Mazal, D. Thoss, G. Dogaer, J. Backhouse, G. Dalli Regoli, H. Künzl).

- Florentine Mütherich, Joachim E. Gaehde: Karolingische Buchmalerei. Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0395-3

- Florentine Mütherich: Die Erneuerung der Buchmalerei am Hof Karls des Großen, in: 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit. Vol. 3: Beiträge zum Katalog der Ausstellung Paderborn 1999. Handbuch zur Geschichte der Karolingerzeit. Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2456-1, pp. 560–609

- Christoph Stiegemann, Matthias Wemhoff: 799. Kunst und Kultur der Karolingerzeit. Karl der Große und Papst Leo III. in Paderborn. Vols. 1 and 2: Katalog der Ausstellung Paderborn 1999. Vol. 3: Beiträge zum Katalog der Ausstellung Paderborn 1999. Handbuch zur Geschichte der Karolingerzeit. Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2456-1

- Ingo F. Walther, Norbert Wolf: Meisterwerke der Buchmalerei. Taschen, Cologne et al. 2005, ISBN 3-8228-4747-X

- Michael Embach, Claudine Moulin und Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: Die Handschriften der Hofschule Kaiser Karls des Großen. Individuelle Gestalt und europäisches Kulturerbe, Verlag für Geschichte und Kultur, Trier 2019, ISBN 978-3-945768-11-2