Camera Work

This article contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (December 2024) |

Camera Work was a quarterly photographic journal published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917. The journal presented photogravures and aimed to establish photography as a fine art. Since its release, Camera Work has been described as "consummately intellectual,”[1] and "a portrait of an age in which the artistic sensibility of the nineteenth century was transformed into the artistic awareness of the present day."[2]

Background

[edit]Alfred Stieglitz was an American photographer, editor, and publisher active in the 20th century.[3] He believed photography was a new field of expression and creation, equivalent to fine art. He promoted this philosophy, a component of Pictorialism,[4] by writing articles and organizing photography exhibitions. During his five-year tenure as editor of the journal Camera Notes (published by the Camera Club of New York), he attempted to change the perspective that photography was merely technical, held by the club's more traditional members. In 1902, he resigned as editor of Camera Notes due to his failure to change the club's view of photography as an art form.[5]

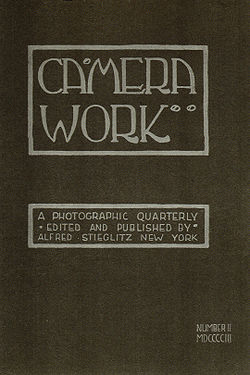

At the encouragement of close friend and fellow photographer Joseph Keiley, among others, Stieglitz developed the idea of an independent photography magazine free of conservative influences. In August 1902, he printed a two-page prospectus "in response to the importunities of many serious workers in photographic fields that I should undertake the publication of an independent magazine devoted to the furtherance of modern photography."[5] He stated the magazine would be self-published, and "owing allegiance only to the interests of photography."[5] The name Camera Work was a reference to the phrasing in his prospectus, meant to distinguish artistic photographers from the old-school technicians which frustrated him. To emphasize the journal's independent nature, every cover was imprinted with "Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly, Edited and Published by Alfred Stieglitz, New York".[6]

Design and production

[edit]

Stieglitz appointed Edward Steichen to design the cover: a plain, gray-green background with the magazine's title, acknowledgement of Stieglitz's editorial control, issue number, and date. These details were all set in an Art Nouveau-style typeface that Steichen created specifically for the journal. The advertisements at the back of each issue were also creatively designed and presented, often by Stieglitz himself. Eastman Kodak took the back cover ad for almost every issue, using the same typeface Steichen had designed for the cover at Stieglitz's insistence.[7]

Gravures were produced from the photographers' original negatives whenever possible. If the gravure came from a negative, this fact was noted in the accompanying text, and these gravures were noted to be original prints.[7]

Stieglitz personally tipped-in the photogravures in every issue, touching up dust spots or scratches when necessary.[8] This assured only the highest standards in all copies of the magazine, but sometimes delayed mailing. Stieglitz would not allow anyone else to tip in. When a set of prints failed to arrive for a Photo-Secession exhibition in Brussels, gravures from the magazine were hung instead. Because of their high visual quality, most viewers assumed they were looking at the original photographs.[5]

Before the first issue was printed, Stieglitz received 68 subscriptions for the new publication. Stieglitz insisted that 1000 copies of each issue be printed, regardless of the number of subscriptions. Under financial duress, he reduced the number to 500 for the final two issues. As of the first issue, the subscription rate was US $4 yearly, or US $2 for single issues.[7]

Publishing history

[edit]

Camera Work was published as a series of 50 issues between 1903 and 1917.

1903–1906

[edit]The inaugural issue of Camera Work was dated January 1903, but was actually mailed on December 15, 1902. In it, Stieglitz set forth the mission of the new journal:

"Photography being in the main a process in monochrome, it is on subtle gradations of tone and value that its artistic beauty so frequently depends. It is therefore highly necessary that reproductions of photographic work must be made with exceptional care, and discretion of the spirit of the original is to be retained, though no reproductions can do justice to the subtleties of some photographs. Such supervision will be given to the illustrations that will appear in each number of Camera Work. Only examples of such works as gives evidence of individuality and artistic worth, regardless of school, or contains some exceptional feature of technical merit, or such as exemplifies some treatment worthy of consideration, will find recognition in these pages. Nevertheless, the Pictorial will be the dominating feature of the magazine."[9]

In his first editorial, Stieglitz expressed gratitude to a group of photographers to whom he was indebted. He listed them in the following order: Robert Demachy, Will Cadby, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Frank Eugene, James Craig Annan, Clarence H. White, William Dyer, Eva Watson, Frances Benjamin Johnston, and R. Child Baley.[10] Over the next fourteen years, he published many of their photographs.[5]

During this early period, Stieglitz used Camera Work to expand the same vision and aesthetics that he had promoted in Camera Notes. He used the services of the same three assistant editors who worked with him on Camera Notes: Dallett Fuguet, Joseph Keiley, and John Francis Strauss. Over the years, both Fuguet and Keiley contributed extensively to the journal through their own articles and photographs.[11] Strauss’ role appears to have been more in the background. Neither Stieglitz nor his associate editors received a salary for their work, nor were any photographers paid for having their work published.[5]

One of the purposes of the new journal was to serve as a vehicle for the Photo-Secession, an invitation-only group that Stieglitz founded in 1902 to promote photography as an art form.[7] Much of the work published in Camera Work came from the Photo-Secession exhibitions he hosted, and soon rumors circulated that the magazine was intended only for those involved in the Photo-Secession. In 1904, Stieglitz attempted to counter this idea by publishing a full-page notice in the journal in order to correct the "erroneous impression…that only the favored few are admitted to our subscription list." He then went on to say, "…although it is the mouthpiece of the Photo-Secession that fact will not be allowed to hamper its independence in the slightest degree."[9]

While making this proclamation in the journal, Stieglitz continued to unabashedly promote the Photo-Secession in its pages. In 1905, he wrote, "the most important step in the history of the Photo-Secession," was taken with the opening of his photography gallery that year. "Without the flourish of trumpets, without the stereotypes, press-view or similar antiquated functions, the Secessionists and a few friends informally opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York."[8]

1907–1909

[edit]Throughout its publication, Camera Work became intertwined with all aspects of Stieglitz's life. He lived to promote photography as an art form and to challenge the norms of how art is defined.[5] As his own successes increased, from recognition of his own photos and through his efforts to organize international exhibitions of photography, the content of Camera Work reflected these changes. Articles began to appear with such titles as "Symbolism and Allegory" (Charles Caffin, No 18 1907) and "The Critic as Artist" (Oscar Wilde, No 27 1909), and the focus of Camera Work turned from primarily American content to a more international scope.

Stieglitz also continued to intertwine the walls of his galleries with the pages of his magazine. Stieglitz's closest friends (Steichen, Demachy, White, Käsebier and Keiley) were represented in both, while many others were granted one but not the other.[10] Increasingly, a single photographer was given the preponderance of coverage in an issue, and in doing so Stieglitz relied more and more on his small circle of old supporters. This led to increased tensions among Stieglitz and some of his original colleagues, and when Stieglitz began to introduce paintings, drawings and other art forms in his gallery, many photographers saw it as the breaking point in their relationship with Stieglitz.

In 1909, Stieglitz was notified about yet another sign of the increasingly difficult times. London's Linked Ring, which for more than a decade Stieglitz had looked to as model for the Photo-Secession, finally dissolved.[5] Stieglitz knew this signaled the end of an era, but rather than be set back by these changes, he began making plans to integrate Camera Work even further into the realm of modern art.

1910–1914

[edit]

In January, 1910, Stieglitz abandoned his policy of reproducing only photographic images, and in issue 29 he included four caricatures by Mexican artist Marius de Zayas. From this point on Camera Work would include both reproductions of and articles on modern painting, drawing and aesthetics, and it marked a significant change in both the role and the nature of the magazine. This change was brought about by a similar transformation at Stieglitz's New York gallery, which had been known as the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession until 1908. That year he changed the name of the gallery to "291", and he began showing avant-garde modern artists such as Auguste Rodin and Henri Matisse along with photographers. The positive responses he received at the gallery encouraged Stieglitz to broaden the scope of Camera Work as well, although he decided against any name change for the journal.[2]

This same year a huge retrospective exhibition of the Photo-Secession was held at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. More than 15,000 people visited the exhibition over its four-week showing, and at the end the Gallery purchased twelve prints and reserved one room for the permanent display of photography. This was the first time a museum in the U.S. acknowledged that photography was in fact an art form, and, in many ways, it marked the beginning of the end for the Photo-Secession.[2]

After the Buffalo show, Stieglitz began showcasing more art in Camera Work. In 1911, a double issue was devoted to reproductions and analysis of Rodin's drawings, and analysis of the work of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso. While this was a very bold move to promote modern art, it did not sit well with the photographers who still made up most of the subscription list. Half of the existing subscribers immediately cancelled their subscriptions.[2]

By 1912, the number of subscriptions had dropped to 304. The shift away from photography to a mix of other art and photography had cost Stieglitz many subscribers,[7] but he did not change his editorial direction. To inflate the issues' marketplace value and attract subscribers, Stieglitz began to destroy unwanted copies. The price of back issues soon increased substantially, but the number of paid subscriptions continued to dwindle.[7]

1915–1917

[edit]By 1915, the cultural changes and the economic effects of the war finally took its toll on Camera Work. The number of subscribers dwindled to just thirty-seven, and both the costs and even the availability of the paper on which it was printed became challenging. Coupled with the public's decreased interest in pictorial photography, these problems simply became too much for Stieglitz to bear. He published issue 47 in January, 1915, and devoted most of it what Steichen referred to as a "project in self-adulation".[2] Three years earlier Stieglitz had asked many of his friends to tell him what his gallery "291" meant to them. He received sixty-eight replies and printed all of them, unedited (including Steichen's previously mentioned opinion), in issue 47. As another sign of the changing times, only four of the comments came from photographers – all of the rest were from painters, illustrators and art critics.[5] It was the only issue that did not include an illustration of any kind.

Issue 48 did not appear until October 1916, sixteen months later. In the interim, two important events occurred. At the insistence of his friend Paul Haviland, Stieglitz began releasing another journal, 291, which was intended to bring attention to his gallery of the same name. This effort occupied much of Stieglitz's time and interest from the summer of 1915 until the last issue was published in early 1916. In April 1916, Stieglitz finally met Georgia O'Keeffe, although the latter had gone to see exhibits at "291" since 1908. The two immediately were attracted to each other, and Stieglitz began devoting more and more of his time to their developing relationship.

In issue 48, Stieglitz introduced the work of a young photographer, Paul Strand, whose photographic vision was indicative of the aesthetic changes now at the heart of Camera Work's demise. Strand shunned the soft focus and symbolic content of the Pictorialists and instead strove to create a new vision that found beauty in the clear lines and forms of ordinary objects. By publishing Strand's work, Stieglitz was hastening the end of the aesthetic vision he had championed for so long.[11]

In June 1917, the final issue of Camera Work was published. This issue was devoted almost entirely to Strand's photographs. Even after the difficulties of publishing the last two issues, Stieglitz did not indicate he was ready to give up; he included an announcement that the next issue would feature O’Keefe's work. Soon after publishing this issue, however, Stieglitz realized that he could no longer afford to publish Camera Work or to run "291" due to the effect of the war and the changes in the New York art scene. He ceased publication of both journals with no formal announcement or notice.

After ending publication, Stieglitz had several thousand unsold copies of Camera Work, along with more than 8,000 unsold copies of 291. He sold most of these in bulk to a ragman, and gave away or destroyed the rest. Almost all extant copies came from original subscribers' collections.

Legacy

[edit]For most of its life, Camera Work was universally praised by both photographers and critics. Critics wrote the following upon the first publication of Camera Work:

- "When Camera Notes was at its height, it seemed impossible for it to be surpassed. We can only say that in this case it has been passed, that Stieglitz has out-Stieglitzed Stieglitz and that, in producing Camera Work he has beaten that record which he himself held, which no one else has ever approached."[12]

- "For Camera Work as a whole we have no words of praise too high, it stands alone; and of Mr. Alfred Stieglitz American photographers may well be proud. It is difficult to estimate how much he has done for the good of photography, working for years against opposition and without sympathy, and it is to his extraordinary capacity for work, his masterful independence which compels conviction, and his self-sacrificing devotion that we owe the beautiful work before us."[13]

Despite Stieglitz's initial statement that Camera Work "owes allegiance to no organization or clique",[9] in the end it was primarily a visual showcase for his work and that of his close friends. Of the 473 photographs published in Camera Work during its fifteen-year publication, 357 were the work of just fourteen photographers: Stieglitz, Steichen, Frank Eugene, Clarence H. White, Alvin Langdon Coburn, J. Craig Annan, Hill & Adamson, Baron Adolf de Meyer, Heinrich Kühn, George Seeley, Paul Strand, Robert Demachy, Gertrude Käsebier and Anne Brigman. The remaining 116 photographs came from just thirty-nine other photographers.[5]

Three complete sets of Camera Work have notably sold at auction: a complete set of all 50 in original binding sold at Sotheby's in October 2011 for $398,500;[14] a second complete set, kept in contemporary clamshell cases, sold in 2007 for $229,000;[15] and a complete set bound into book volumes sold in October 2016 for $187,500.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

York Minster: 'In sure and Certain Hope', by Frederick H. Evans. Camera Work No 4, 1903

-

Severity, by Robert Demachy. Camera Work No 5, 1904

-

The Rose, by Eva Watson-Schütze. Camera Work No 9, 1905

-

Experiment in Three-Color Photography, by Edward Steichen. Camera Work No 15, 1906

-

Miss Doris Keane, by Paul B. Haviland. Camera Work No 39, 1912

-

Mary, by Sarah Choate Sears. Camera Work No 18, 1907

-

Black Bowl, by George Seeley. Camera Work No 20, 1907

-

Spider-webs, by Alvin Langdon Coburn. Camera Work No 21, 1908

-

Drops of Rain, by Clarence H. White. Published in Camera Work No 23, 1908

-

Dawn, by Alice Boughton. Camera Work No 26, 1909

-

The White House, James Craig Annan. Camera Work No 32, 1910

-

The Steerage, by Alfred Stieglitz. Camera Work No 36, 1911

-

Drawing (Nude), by Auguste Rodin. Published in Camera Work No 34/35, 1911

-

Marchesa Casati, by Adolf de Meyer. Camera Work No 40, 1912

-

A Snapshot: Paris, by Alfred Stieglitz. Camera Work No 41, 1913

-

Group on a Hill Road - Granada, by J. Craig Annan. Camera Work No 45, 1914

-

Theodore Roosevelt, by Marius De Zayas. Published in Camera Work No 46, 1914

-

White Fence, by Paul Strand. Published in Camera Work, No 49-50, 1917

See Also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Andrew Roth (2001). The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century. NY: PPP Editions. p. 7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b c d e Jonathan Green (1973). Camera Work: A Critical Anthology. NY: Aperture. pp. i, 12–23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Richard Whelan (2000). Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Writings. Millerton, NY: Aperture. p. ix.

- ^ Alfred Stieglitz. Camera Work. The complete Photographs 1903-1917. Taschen TMC Art. 1997. pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Richard Whelan (1995). Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography. NY: Little, Brown. pp. 189–223. ISBN 978-0-316-93404-6.

- ^ "Camera Work: Back In Print | PhotoSeed". Retrieved September 26, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Camera Work: The Complete Photographs 1903-1917. Taschen. 2008.

- ^ a b Dorothy Norman (1973). Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer. NY: Random House. pp. 48–68.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b c Alfred Stieglitz (January 1903). "Introduction". Camera Work (1): 4.

- ^ a b Weston Naef (1978). The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 120–134.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b Katherine Hoffman (2004). Stieglitz : A Beginning Light. New Haven: Yale University Press Studio. pp. 213–222.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ R. Child Bayley (1903). "Camera Work". Photography. 15: 738.

- ^ A. Horsley Hinton (January 1903). "Camera Work". The Amateur Photographer. 37 (953): 4.

- ^ "Sotheby's: Alfred Stieglitz, Editor: Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly". Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Sotheby's: Alfred Stieglitz, Editor: Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly". Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Sotheby's: Alfred Stieglitz, Editor: Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly". Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Find here every photogravure from Camera Work

- Camera Work at The Modernist Journals Project: a cover-to-cover, searchable digital edition of all 50 issues, from January 1903 (No. 1) through June 1917 (No. 49-50). PDFs of all 50 issues may be downloaded for free from the MJP website.

- Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly online at Heidelberg University Library

- Facsimile set of Camera Work, republished