Bering Strait crossing

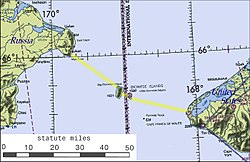

A Bering Strait crossing is a hypothetical bridge or tunnel that would span the relatively narrow and shallow Bering Strait between the Chukotka Peninsula in Russia and the Seward Peninsula in the U.S. state of Alaska. The crossing would provide a connection linking the Americas and Afro-Eurasia.

With the two Diomede Islands between the peninsulas, the Bering Strait could be spanned by a bridge or tunnel.

There have been several proposals for a Bering Strait crossing made by various individuals and media outlets. The names used for them include "The Intercontinental Peace Bridge" and "Eurasia–America Transport Link".[1] Tunnel names have included "TKM–World Link", "AmerAsian Peace Tunnel", and InterBering.[2] In April 2007, Russian government officials told the press that the Russian government would back a US$65 billion plan by a consortium of companies to construct a Bering Strait tunnel.[3]

History

[edit]

19th century

[edit]The concept of an overland connection crossing the Bering Strait goes back to the 19th century. William Gilpin, first governor of the Colorado Territory, envisaged a vast "Cosmopolitan Railway" in 1890 that would connect the entire world through a series of railways.[4][5]

Two years later, Joseph Strauss, who went on to design over 400 bridges and then serve as the project engineer for the Golden Gate Bridge, put forward the first proposal for a Bering Strait rail bridge in his senior thesis.[6] The project was presented to the government of the Russian Empire, but it was rejected.[7]

20th century

[edit]In 1904, a syndicate of American railroad magnates proposed (through a French spokesman) a Siberian–Alaskan railroad from Cape Prince of Wales in Alaska through a tunnel under the Bering Strait and across northeastern Siberia to Irkutsk via Cape Dezhnyov, Verkhnekolymsk, and Yakutsk (around 5,000 km [3,100 mi] of railroad to build, plus over 3,000 km [1,900 mi] in North America). The proposal was for a 90-year lease and exclusive mineral rights for 13 km (8 mi) on each side of the right-of-way. It was debated by officials and finally turned down on March 20, 1907.[8]

Czar Nicholas II approved the American proposal in 1905 (only as a permission, not much financing from the Czar).[9] Its cost was estimated at $65 million[10] and $300 million, including all the railroads.[9] These hopes were dashed with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution of 1905, followed by World War I.[11]

There was a Nazi plan to create a wide-gauge railroad called the Breitspurbahn to connect the cities of Europe, India, China, and ultimately North America via the Bering Strait.[citation needed]

Interest was renewed during World War II with the completion in 1942–1943 of the Alaska Highway, linking the remote territory of Alaska with Canada and the continental United States. In 1942, the Foreign Policy Association envisioned the highway continuing to link with Nome near the Bering Strait, linked by highway to the railhead at Yakutsk, using an alternative sea-and-air ferry service across the Bering Strait.[12] At the same time, the road on the Russian side was extended by building the 2,000-kilometer (1,200 mi) Kolyma Highway.[citation needed]

In 1958, engineer Tung-Yen Lin suggested the construction of a bridge across the Bering Strait "to foster commerce and understanding between the people of the United States and the Soviet Union."[13] Ten years later, he organized the Inter-Continental Peace Bridge, Inc., a nonprofit institution organized to further this proposal.[13] At that time, he made a feasibility study of a Bering Strait bridge and estimated the cost to be $1 billion for the 80 km (50 mi) span.[14] In 1994, he updated the cost to more than $4 billion. Like Gilpin, Lin envisioned the project as a symbol of international cooperation and unity, and dubbed the project the Intercontinental Peace Bridge.[15]

21st century

[edit]According to a report in the Beijing Times in May 2014, Chinese transport experts had proposed building a roughly 10,000-kilometer (6,200 mi) high-speed rail line from northeast China to the United States.[16] The project would include a tunnel under the Bering Strait and connect to the contiguous United States via Wales, Alaska, along the river to Fairbanks, Alaska, and along the Alaska Highway to Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.[citation needed]

Several American entrepreneurs have also advanced private-sector proposals, such as an Alaska-based limited-liability company, InterBering, founded in 2010 to lobby for a cross-straits connection, and a 2018 cryptocurrency offering to fund the construction of a tunnel.[17][18][19] In 2005, investor Neil Bush, younger brother of U.S. President George W. Bush and son of President George H. W. Bush, traveled abroad with Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church as he promoted a proposal to dig a transportation corridor beneath the Bering Strait. When questioned by Mother Jones during the Republican primary campaign of his brother Jeb Bush a decade later in 2015, he denied having supported the tunnel project and said that he had traveled with Moon because he supported "efforts by faith leaders to call their flock into service to others."[20]

Strategic military concerns

[edit]Proposals to construct a strait crossing predate the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Russo-Ukrainian war, which began in February 2014. Russia's actions have raised serious scepticism about its possible realization in the near future, especially regarding the proposed crossing's impact on the national security of the United States and Canada, considering that such a bridge or a tunnel would effectively enable Russian armed forces, paramilitary troops, spies, and saboteurs to gain a land bridge directly to North America.[21][22] Even before the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, commentators on the proposed link have flagged strategic military concerns as a factor in any decision to build the crossing.[23][24][25]

Technical concerns

[edit]

Geologic faults

[edit]Several major geologic faults run through the Bering Strait region, although some are offshore, and their exact offshore extent is still debated. Key faults include the Kaltag and Bendeleben faults on land, and the Bering Fracture Zone offshore, which is the site of significant seismic activity and tectonic plate boundaries.

Distance

[edit]The straight distance between Russia and Alaska is 82.5 kilometers (51.3 mi). If the two parts would be connected by building a bridge, or, even more likely, a series of bridges, while using the Diomede Islands as intermediate points, the length of the three separate bridges, spanning across water from one island to another, would be 36.0 km (22.4 mi), 3.8 km (2.4 mi), and 36.8 km (22.9 mi), or 76.6 km (47.6 mi) in total.[26][27][28]

Depth of water

[edit]The depth of the water is a minor problem, as the strait is no deeper than 55 meters (180 ft),[15] comparable to the English Channel. The tides and currents in the area are not severe.[13]

Weather-related challenges

[edit]Restrictions on construction work

[edit]The route is just south of the Arctic Circle, and the location has long, dark winters and extreme weather, including average winter lows of −20 °C (−4 °F) and temperatures approaching −50 °C (−58 °F) in cold snaps. This would mean that construction work would likely be restricted to five months of the year, around May to September, and centered during the summer.[15]

Exposed steel

[edit]The extreme arctic weather also poses a significant challenge to exposed steel and other construction materials.[clarification needed][15][29] In Lin's design, concrete covers all structures to simplify maintenance and to offer additional stiffening.[15]

Ice floes

[edit]Although there are no icebergs in the Bering Strait, ice floes up to 1.8 meters (6 ft) thick are in constant motion during certain seasons, which could produce forces on the order of 44 meganewtons (9,900,000 pounds-force; 4,500 tonnes-force) on a pier.[13]

Tundra in the surrounding regions

[edit]Roads on either side of the strait would need to be constructed in a way that enables them to cross extensive areas of tundra unhindered, requiring either an unpaved road or another solution to avoid the obstructing effects of permafrost.[30][31][32]

Likely route and expenses

[edit]

Bridge option

[edit]If the bridge is chosen over the tunnel as a type of fixed-link crossing, the most technically and economically feasible option would be to connect Wales, Alaska, to a location south of Uelen. In this case, predictions suggest that the link would likely not consist of a single, uninterrupted bridge but would rather be divided into several bridges that would be interconnected with each other by the Diomede Islands, located in the middle of the Bering Strait.[33]

In 1994, Lin estimated the cost of a bridge to be "a few billion" dollars.[15] The roads and railways on each side were estimated to cost $50 billion.[15] Lin contrasted this cost to petroleum resources "worth trillions".[15] Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering estimates the cost of a highway, electrified double-track high-speed rail, and pipelines at $105 billion (in 2007 US dollars), five times the original cost of the 1994 50-kilometer (31 mi) Channel Tunnel.[34]

Connections to the rest of the world

[edit]This excludes the cost of new roads and railways to reach the bridge. Aside from the technical challenges of building two 40-kilometer (25 mi) bridges or a more than 80-kilometer (50 mi) tunnel across the strait, another major challenge is that, as of 2022[update], there is nothing on either side of the Bering Strait to connect the bridge to.

The Russian side of the strait, in particular, is severely lacking in infrastructure. No railways exist for over 2,800 kilometers (1,700 mi) in any direction from the strait.[35] The nearest major connecting highway is the M56 Kolyma Highway, which is currently unpaved and around 2,000 kilometers (1,200 mi) from the strait.[36] However, by 2042, the Anadyr Highway is expected to be completed, connecting Ola and Anadyr, which is only about 600 kilometers (370 mi) from the strait.[37]

On the U.S. side, an estimated 1,200 kilometers (750 mi) of highways or railroads would have to be built around Norton Sound, through a pass along the Unalakleet River, and along the Yukon River to connect to Manley Hot Springs Road – in other words, a route similar to that of the Iditarod Trail Race. A project to connect Nome, 160 kilometers (100 mi) from the strait, to the rest of Alaska by a paved highway (part of Alaska Route 2) has been proposed by the Alaskan state government, although the very high cost ($2.3 to $2.7 billion, about $3 million per kilometer, or $5 million per mile) has so far prevented construction.[38]

In 2016, the Alaskan road network was extended westwards by 80 kilometers (50 mi) to Tanana, 740 kilometers (460 mi) from the strait, by building a relatively simple road. The Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities project was supported by local indigenous groups such as the Tanana Tribal Council.[39]

Track gauge

[edit]

Another complicating factor is the different track gauges in use. Mainline rail in the US, Canada, China, and the Koreas uses a standard gauge of 1435 millimeters. Russia uses the slightly broader Russian gauge of 1520 mm.

Solutions to this break of gauge include:

- To have all cargo in containers, which are fairly easily reloaded from one train to another. This is used on the increasingly popular China–Europe rail freight route, which has two breaks of gauge. It is possible to transfer a 60-container train in one hour.[citation needed]

- Another solution is variable gauge axles for locomotives and rolling stock, such as those made by Talgo. A gauge changer modifies the gauge of the wheels while the train traverses the GC equipment at a speed of 15 km/h (4.2 m/s), which is about 4 seconds per railcar. This is faster than is possible with the transfer of ISO containers.[citation needed]

The TKM–World Link

[edit]

The TKM–World Link (Russian: ТрансКонтинентальная магистраль, English: Transcontinental Railway), also called ICL-World Link (Intercontinental link), was a planned 6,000-kilometer (3,700 mi) link between Siberia and Alaska to deliver oil, natural gas, electricity, and rail passengers to the United States from Russia. Proposed in 2007, the plan included provisions to build a 103-kilometer (64 mi) tunnel under the Bering Strait, which, if built, would have been the longest tunnel in the world,[40] surpassing the 60-kilometer (37 mi) Line 3 (Guangzhou Metro) tunnel. The tunnel was intended to be part of a railway joining Yakutsk, the capital of the Russian republic of Yakutia, and Komsomolsk-on-Amur, in the Russian Far East, with the western coast of Alaska.[41] The Bering Strait tunnel was estimated to cost between $10 billion and $12 billion, while the entire project was estimated to cost $65 billion.[40]

In 2008, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin approved the plan to build a railway to the Bering Strait area, as part of a development plan to run until 2030. The more than 100-kilometer (60 mi) tunnel would have run under the Bering Strait between Chukotka, in the Russian far east, and Alaska.[42] The cost was estimated as $66 billion.[43]

In late August 2011, at a conference in Yakutsk in eastern Russia, the plan was backed by some of President Dmitry Medvedev's top officials, including Aleksandr Levinthal, the deputy federal representative for the Russian Far East.[41] Supporters of the idea believed that it would be a faster, safer, and cheaper way to move freight around the world than container ships.[41] They estimated it could carry about 3% of global freight and make about $7 billion a year.[41] Shortly after, the Russian government approved the construction of the $65 billion Siberia-Alaska rail and tunnel across the Bering Strait.[42]

Observers doubted that the rail link would be cheaper than transport by shipping, bearing in mind that the cost for rail transport from China to Europe is higher than by ship (except for expensive cargo where lead time is important).[44]

In 2013, the Amur–Yakutsk Mainline connecting the Yakutsk railway (2,800 km or 1,700 mi from the strait) with the Trans-Siberian Railway was completed. However, this railway is meant for freight and is too tightly curved for high-speed passenger trains. Future projects include the Lena–Kamchatka Mainline and Kolyma–Anadyr highway. The Kolyma–Anadyr highway has started construction, but will be a narrow gravel road.[citation needed]

US–Canada–Russia–China railway

[edit]In 2014, China was considering the construction of a US-Canada-Russia-China 350 km/h (220 mph) bullet train that would be 13.000 kilometers (8,078 miles) long and would include a 200-kilometer (120 mi) underwater tunnel crossing the Bering Strait, allowing passengers to travel between the United States and China in approximately two days.[45][46][47]

Although the press was skeptical of the project, China's government-run media agency, China Daily, claimed that China possessed the necessary technology.[48] It was unknown who was expected to pay for the construction, although China had, in multiple other construction projects, offered money and assistance to build and finance them; however, upon the projects' completion, it regularly demanded the return of the money through fees or rents.[49][50][51]

Trans-Eurasian Belt Development

[edit]In 2015, another possible collaboration between China and Russia was reported, part of the Trans-Eurasian Belt Development, a transportation corridor across Siberia that would also include a road bridge with gas and oil pipelines between the easternmost point of Siberia and the westernmost point of Alaska. It would link London and New York by rail and superhighway via Russia if it were to go ahead.[52]

China's Belt and Road Initiative has similar plans, so the project would work in parallel for both countries.[53]

See also

[edit]- Alaska-Alberta Railway Development Corporation

- Artificial island

- Beringia

- Cosmopolitan Railway

- Eurasian Land Bridge

- Intercontinental and transoceanic fixed links

- Land reclamation

- List of straits

- Pan-American Highway

- Transportation in Alaska

- Transport in Russia

References

[edit]- ^ A Transcontinental Eurasia-America Transport Link via the Bering Strait, at the 1st International Conference "Megaprojects of the Russian East"

- ^ "InterBering".

- ^ "Russia wants a rail link to North America". Der Spiegel. April 20, 2007.

- ^ Cole, Dermot (April 1, 2019). "Is the world ready for a Bering Strait rail link between Alaska and Russia?". ArcticToday. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ "InterBering :: Thinking Big — Roads and Railroads to Siberia, by Terrence Cole. Visions of the Bering Strait Tunnel". www.interbering.com. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Kevin Starr. Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California, 330. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-510080-8

- ^ An excerpt from memoirs Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine of the Russian Empire Minister of Land Forces Aleksandr Rediger (in Russian)

- ^ Theodore Shabad and Victor L. Mote: Gateway to Siberian Resources (The BAM) pp. 70-71 (Halstead Press/John Wiley, New York, 1977) ISBN 0-470-99040-6

- ^ a b "Czar Authorizes American Syndicate to Begin Work". The New York Times. August 2, 1906. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

The Czar of Russia has issued an order authorizing the American syndicate, represented by Baron Loicq de Lobel, to begin work on the TransSiberian-Alaska ...

- ^ Burr, William H. (January 1907). "Around the World by Rail". Locomotive Engineers Journal. 41. Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers: 108–111.

- ^ Halpin, Tony (April 20, 2007). "Russia plans $65bn tunnel to America". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ "Airway to Russia via Alaska Urged; Foreign Policy Association Also Favors Northern Sea Route and Bering Link". The New York Times. July 20, 1942. p. 3. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Troitsky, M. S. (1994). "1.10.4 Bering Strait Bridge Project". Planning and design of bridges (illustrated ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-471-02853-6.

- ^ "Engineer feels Bering Strait Bridge Possible". The Bulletin. April 23, 1969. p. 12. Retrieved October 11, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pope, Gregory (April 1994). "Last Great Engineering Challenge: Alaska-Siberia Bridge". Popular Mechanics. 171 (4). Hearst Magazines: 56–58. ISSN 0032-4558.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (May 9, 2014). "China may build an undersea train to America". The Washington Post.

- ^ Shirk, Adrian (July 1, 2015). "A Superhighway Across the Bering Strait". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ About InterBering: "Our expertise includes the integration of information and management processes for the organization, financing and construction of an interhemispheric Bering Strait tunnel and joining the railways of two continents, North America and Asia."

- ^ "Beringia". Beringia.io. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Tim (January 6, 2015). "Here Is a Crazy Story About Jeb Bush's Brother and a $400 Billion Tunnel to Russia That Wasn't Meant to Be". Mother Jones. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Malgin, Andrei (October 24, 2025). "Here's Why Plans for a Tunnel Between Russia and Alaska Are Insane". The Moscow Times. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew. "Kremlin envoy proposes a 'Putin-Trump tunnel' to link Russia and US, with Elon Musk's help". USA TODAY. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Adrian Shirk, "A Superhighway Across the Bering Strait", The Atlantic, 1 July 2015: "The issue left unaddressed in both my conversations with Cooper and Soloview is that none of this would be possible unless current diplomatic tensions are resolved..."

- ^ Louis P. Bergeron, "The Bering Strait: Choke Point of the Future?", Second Line of Defense, 19 November 2015: "However, the geopolitics of the strait and the Arctic have turned frosty again since Russia’s involvement in Ukraine and now in Syria; the Bering Strait again has a front row seat to a declining Great Power relationship between the United States and Russia."

- ^ Riccardo Rossi, "The Bering Strait, an area of Russian-US geostrategic interest" Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598 Volume 16 Issue 1, SpecialEurAsia, 7 February 2022: "This concentration of interests has led Washington to identify the following political-strategic priorities in the Bering Strait: to ensure the defence of the State of Alaska, to preserve the freedom of navigation in the strait, to exploit the fossil resources present in the Chukchi Sea and to enhance its territory near the Bering Sea as a base to launch possible air-naval operations in the North Pacific Area."

- ^ "Google Maps".

- ^ khwang562 (August 11, 2025). "Proposal for a Bering Strait Peace Tunnel". UPF International. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Russia Connection: Historical Proposals to Reestablish a Land Link across the Bering Strait | Readex". www.readex.com. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Friedrich, Doris (August 9, 2022). "Past, Present, and Future Themes of Arctic Infrastructure and Settlements". The Arctic Institute - Center for Circumpolar Security Studies. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ "How To Build Infrastructure in Extreme Cold Climate -". January 27, 2025. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Box 1343Yellowknife, Contact Information Up Here PublishingP O.; Email, NTX1A 2N9 Canada (November 20, 2025). "Fixing The North's Melting Highways". Up Here Publishing (in Catalan). Retrieved November 22, 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Proulx, André (April 8, 2020). "Permafrost thaw and northern infrastructure". ArcticNet. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Wright, Emily (November 1, 2024). "The incredible £50.3bn tunnel that would link two continents". Express.co.uk. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ "Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ^ "Trip from Russia to USA may take one hour soon". April 8, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ "Google Earth". earth.google.com. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Project to build road from Kolyma to Anadyr drawn up". TASS (in Russian). June 23, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Cockerham, Sean (January 27, 2010). "Nome road could cost $2.7 billion". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "Tanana Road opens". Alaska Public Media. September 5, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Humber, Yuriy; Bradley Cook (April 18, 2007). "Russia Plans World's Longest Tunnel, a Link to Alaska". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Report: Tunnel linking US to Russia gains support". NBC News. August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Russia Green Lights $65 Billion Siberia-Alaska Rail and Tunnel to Bridge the Bering Strait!". August 23, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Nicola; Hutchins, Chris (March 30, 2008). "Bridgebuilding Vladimir Putin wants tunnel to US". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Logistics concept for the Chinese growth market". Deutsche Bahn. March 2014. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014.

- ^ Tharoor, Ishaan (May 9, 2014). "China may build an undersea train to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Politi, Daniel (May 10, 2014). "Report: China Mulls Construction of a High Speed Train to the U.S." Slate. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ "China Wants To Build An 8,000-Mile Underwater Train Line To The USA". IFLScience. May 28, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ "China mulls high-speed train to US: report". China Daily. May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ Mutai, Noah (March 5, 2025). "China's Debt to Africa: A Balancing Act Between Development and Dependency | Democracy in Africa". Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ "China's Debt-Trap Diplomacy in Central Asia". www.cacianalyst.org. Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Simon, Dorian. "Will the Western Balkan countries fall for China's "debt-trap diplomacy"? | United Europe". Retrieved November 22, 2025.

- ^ Stone, Jon (March 25, 2015). "Russia unveils plans for high speed railway and superhighway to connect Europe and America". The Independent. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Russian, China's trans-Asia programs complementary: railway chief". Archived from the original on August 5, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Oliver, James A (2006). "The Bering Strait Crossing". Information Architects. ISBN 0-9546995-6-4. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Russians dream of tunnel to Alaska". BBC News. January 3, 2001. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- "Russia Considering Tunnel Between Asia and North America". VOA. April 19, 2007. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- Oliver, James A.; Podderegin, Andrey; Mashin, Dmitiri (2007). ICL World Link: Intercontinental Eurasia-America Transport Corridor Via the Bering Strait. The Company of Writers. ISBN 978-0955663802.

External links

[edit]- Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering

- World Peace King Tunnel Archived 2014-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Trans-Global Highway

- The Bering Strait Crossing

- Alaska Canada Rail Link - Project Feasibility Study

- The Bridge Over the Bering Strait by James Cotter

- A Superhighway Across the Bering Strait, The Atlantic

- BART's Underwater Tunnel Withstands Test

- InterBering, LLC - Alaskan company, founded in 2010 by Fyodor Soloview, promoting a tunnel under the Bering Strait and a railroad between North America and Asia: InterBering.com