Abu Simbel

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (April 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

| Location | Aswan Governorate, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Nubia |

| Coordinates | 22°20′13″N 31°37′32″E / 22.33694°N 31.62556°E |

| Type | Temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Ramesses II |

| Founded | Approximately 1264 BC |

| Periods | New Kingdom of Egypt |

| Official name | Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 88 |

| Region | Arab States |

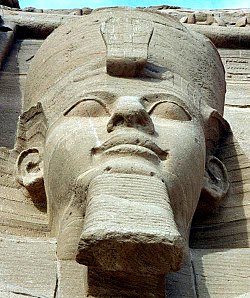

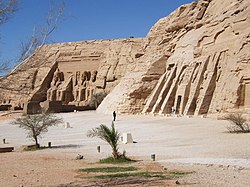

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel (Arabic: أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is located on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about 230 km (140 mi) southwest of Aswan (about 300 km (190 mi) by road). The twin temples were originally carved out of the mountainside in the 13th century BC, during the 19th Dynasty reign of the Pharaoh Ramesses II. Their huge external rock relief figures of Ramesses II have become iconic. His wife, Nefertari, and children can be seen in smaller figures by his feet. Sculptures inside the Great Temple commemorate Ramesses II's heroic leadership at the Battle of Kadesh.

The complex was relocated in its entirety in 1968 to higher ground to avoid it being submerged by Lake Nasser, the Aswan Dam reservoir. As part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, an artificial hill was made from a domed structure to house the Abu Simbel Temples, under the supervision of a Polish archaeologist, Kazimierz Michałowski, from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw.[1][2]

The Abu Simbel complex, and other relocated temples from Nubian sites such as Philae, Amada, Wadi es-Sebua, are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the Nubian Monuments.[2]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]During his reign, Ramesses II embarked on an extensive building program throughout Egypt and Nubia, which Egypt controlled. Nubia was very important to the Egyptians because it was a source of gold and many other precious trade goods. He, therefore, built several grand temples there in order to impress upon the Nubians Egypt's might and Egyptianize the people of Nubia.[3][4] The most prominent temples are the rock-cut temples near the modern village of Abu Simbel, at the Second Nile Cataract, the border between Lower Nubia and Upper Nubia.[4] There are two temples, the Great Temple, dedicated to Ramesses II himself, and the Small Temple, dedicated to his chief wife Queen Nefertari.

Construction of the temple complex started in c. 1264 BC and lasted for about 20 years, until 1244 BC.[citation needed] It was known as the Temple of Ramesses, Beloved by Amun.

Rediscovery

[edit]With the passage of time, the temples fell into disuse and the Great Temple eventually became mostly covered by a sand dune. By the 6th century BC, the sand already covered the statues of the main temple up to their knees.[citation needed] The temple was forgotten by Europeans until March 1813, when the Swiss researcher Johann Ludwig Burckhardt found the small temple and top frieze of the main temple.

When we reached the top of the mountain, I left my guide, with the camels, and descended an almost perpendicular cleft, cloaked with sand, to view the temple of Ebsambal, of which I had heard many magnificent descriptions. There is no road at present to this temple... It stands about twenty feet above the surface of the water, entirely cut out of the almost perpendicular rocky side of the mountain, and in complete preservation. In front of the entrance are six erect colossal figures, representing juvenile persons, three on each side, placed in narrow recesses, and looking towards the river; they are all of the same size, stand with one foot before the other, and are accompanied by smaller figures... Having, as I supposed, seen all the antiquities of Ebsambal, I was about to ascend the sandy side of the mountain by the same way I had descended; when having luckily turned more to the southward, I fell in with what is yet visible of four immense colossal statues cut out of the rock, at a distance of about two hundred yards from the temple; they stand in a deep recess, excavated in the mountain; but it is greatly to be regretted, that they are now almost entirely buried beneath the sands, which are blown down here in torrents. The entire head, and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues are yet above the surface; of the one next to it scarcely any part is visible, the head being broken off, and the body covered with sand to above the shoulders; of the other two, the bonnets only appear. It is difficult to determine, whether these statues are in a sitting or standing posture; their backs adhere to a portion of rock, which projects from the main body, and which may represent a part of a chair, or may be merely a column for support.[5]

In 1815 William John Bankes accompanied only by servants and guides travelled from Cairo up the Nile as far as the Second Cataract area. On the way he visited Abu Simbel, but was unable to enter the Great Temple.[6] He vowed to return with sufficient resources to investigate the site in detail.

In early 1816 the French ex-consul Bernardino Drovetti made an attempt to excavate at Abu Simbel leaving 300 piastres with the local sheikh to pay for dig out the temple entrance, before continuing upriver to Wadi Halfa.[7][8] Upon his return the sheikh returned the money to him as the local Nubians had been unable to comprehend what value these small pieces had metal had and so no work had been undertaken in order to receive them.[9]

A few months later in early September 1816 the Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni arrived, having heard about the site from Burckhardt. [10] He recorded that the Great Temple presented just: ‘one figure of enormous size, with the head and shoulders only projecting out of the sand.’ He was able to convince the sheikh that coins had value and agreed on a price of two piastres a day per man to work at the site. [11] Belzoni succeeded in exposing the figure over the doorway to the Great Temple, and the head and shoulders of the north-central colossi of Ramesses II, before having to abandon the effort to clear the façade of the Great Temple after six days due to a lack of food and money to pay the local Nubians.[9]

With the support of Henry Salt, Consul General of Egypt Belzoni returned in June 1817 to Abu Simbel accompanied by Henry William Beechey, Royal Navy captains Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangles, two servants, and the Italian Giovanni Finati (also known as Mahomet),who had been loaned to them by Salt; supported by what Belzoni considered at times a troublesome crew of five. Eventually after 22 days’ work, he and his party were able to enter the Great Temple on 1 August 1817.[9]

A detailed early description of the temples, together with contemporaneous line drawings, can be found in Edward William Lane's Description of Egypt (1825–1828).[12]

Traveling up the Nile from Cairo the Scottish painter David Roberts reached Abu Simbel on 9 November 1838, and spent time in the area making detailed sketches before returning downstream on 11 November.[13][14] Upon his return to London in 1839, Roberts created detailed watercolours from his sketches. Four watercolours of Abu Simbel were included as lithographs in volumes 4 and 5 of The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia.

- Illustrations created by David Roberts based upon sketches he made in 1865

-

The temples of Abu Simbel

-

The colossal figures in front of the Great Temple

-

The interior of Abu Simbel

-

The inner sanctuary of the Great Temple

Note that Robert's visit was approximately two decades after Belzoni had removed some of the sand to create an entrance to the Great Temple.

In 1842 Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh and his party visited Abu Simbel and were able to enter the Great temple.[15] He reported that the exterior northernmost colossi of Ramesses II bore traces of whitewash having been applied by someone taking a cast of the face.[15]

The first European women to visit Abu Simbel was the English writer Isabella Frances Romer in December 1845, who marked the occasion by cutting her name into the throne of the southern colossus.[16]

The first photographs

[edit]

In 1849 Maxime Du Camp was commissioned by the Ministre de l'Instruction Publique to record monuments and inscriptions in the Middle East using the newly developed photography. Accompanied by his friend the novelist Gustave Flaubert he spent the years from 1849 to 51 completing the mission, which Flaubert recorded in journals and letters, which were later published in English in 1972 as in Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour.[17] After ascending the Nile as far as the second cataract, they stopped on their return downstream at Abu Simbel, arriving on 9am on 27 March i850 and departing on 30 March. [18] After docking he had his crew begin removing the sand from around the head of the fourth colossus of the Great Temple. He commenced taking photographs the following day, taking three of the facade of the Small Temple before on 29 March taking five of the Grand Temple as well as one of the entire complex from the other side of the Nile and dedicated photographs of various aspects of the Great Temple. In a number of photographs Du Camp had his servant and occasional laboratory assistant Louis Sasseti pose to provide scale.[18] At the end of his expedition Du Camp bought back to France 214 photographs of Cairo, Thebes, Philae, Abu Simbel as well as Palestinian and Syrian monuments and landscapes.[19]Of these, 125 calotypes (including 10 of Abu Simbel) were printed by Blanquart-Evrard and included in a book written by Du Camp upon his return to France called Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: Dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les annees 1849, 1850, 1851. Published by Gide and Baudry in 1852 it was the first French printed book to be illustrated with photographs and was a great success.[20]

Du Camp was followed by French civil engineer Félix Teynard (1817-1892) who photographed sites along the Nile River in 1851 and 1852. The resulting photographs were published in thirty-two installments of five plates, beginning in 1853 as Égypte et Nubie: sites et monuments les plus intéressants pour l'étude de l'art et de l'histoire. A complete edition was published in London in 1858. American John Beasley Greene, a Paris-based archaeologist photographed Abu Simbel in 1854.

The best known of the early photographers of Egypt was Englishman Francis Frith, who made three journeys to Egypt, Egypt and the Holy Land between 1856 and 1860, first photographing Abu Simbel in 1857. Other 19th century photographers of Abu Simbel included Pascal Sébah and Antonio Beato.[21]

In the winter of 1873–1874 the writer Amelia Edwards, accompanied by her friend Lucy Renshaw, and the painter Andrew McCallum toured Egypt journeying southwards from Cairo in a hired dahabiyeh (manned houseboat), ultimately reaching Abu Simbel on 31 January 1874, departing down river on 18 February after a four day excursion to Wadi Halfa.[22][23]

In 1874 Thomas Cook instituted a streamer service that operated between Aswan and Wadi Halfa, passing Abu Simbel. The 1892 Baedeker travel guide reported that "Cook's tourist-steamers usually reach Abu-Simbel in the evening of the third day, in time to permit of a visit to the temples before night. Next morning they proceed to Wadi Halfah. On the return-voyage they again spend the night at Abu-Simbel, starting next morning at 9 or 10 o'clock.”[24]

Protecting the great temple

[edit]In December 1892 the Egyptian Public Works Department (PWD) identified that there were insecure amounts of rock overhanging the façade of the Great Temple which if they fell would badly damage the colossi below.[25] At the insistence of William Willcocks of the PWD[26] a request was made to Army Headquarters for the Royal Engineers to undertake an operation to preserve the Great Temple. In response a 12 man detachment of the 24th (Fortress) Company under the command of Lieutenant James Henry L'Estrange Johnstone, arrived at Abu Simbel by the gunboat El Teb on 6 February 1893.[25][27] Arrangements were made for the engineers to be billeted on site in one of Thomas Cook's Post Boats.[25]

Upon arriving they found that a large fragment of rock above the left-hand colossus was found to be close to toppling over on to it while an even larger piece of overhanging rock near another colossus was cracked all round.[27] Many more tons of loose rock also required attention.[25] Great care had to be undertaken as much of the Great Temple was still partly buried under drift sand and the slope was extremely steep. Local Nubians were hired to create a path up a sand slope north of the temple’s façade and along the hillside above. [27]On 10 February a large loose rock poised on the cornice immediately above the temple entrance was removed by means of tackle attached to a holdfast. Two days later, work began on securing a 70 long tons (71 t) rock with a screw jacks and a four-inch steel wire rope attached via a holdfast of steel bars inserted into the level rock above. Once secure to took a week to break it up and remove.[27] On 27 February, while cleaning sand and stones from the rock face above the cornice they found a massive crack that severed an overhanging mass weighing approximately 650 long tons (660 t) from the solid cliff.[27] They made excellent progress breaking it up by mechanical means until they encountered a very hard layer, which would need explosives to break it up.[27] However as they had been forbidden from transporting explosives on the railway and steamboats, they sourced it from 9 pounder ammunition on the El Teb.[25] As each piece was broken off it was hauled up the slope by a winch and tackle, until all that remained was a block of approximately 100 long tons (100 t) weight, lying well back from the edge of a flat ledge.[27][28]

With the cliff face now secure, the removed rock was used to construct two walls at the head of the depression between the two temples to prevent buildup of more drift sand from burying the Great Temple again, and to construct a hard stone slope.[26] The engineers began on 5 April to remove the sand from the entrance to the temple.[27] The engineers also repaired a number of the remaining baboons figures on the cornice with cement and furnished one with a new leg.[27][26] The removal of the sand exposed the unsuspected grave at the southern end of the cutting in the rock, near the Chapel of Thoth. It contained Major Benjamin Tidswell of the Royal Dragoons who had died of dysentery on 18 June 1885, at Abu Simbel while serving with the Nile Expedition's Heavy Camel Regiment. The burial party had heaped sand on top of his grave to protect it from the elements and animals.[28] The engineers also cleared away the material which had become piled up in front of the entrance to the Chapel of Thoth.[26]

The project was completed and inspected by the PWD on the 9 April 1893. In all nearly 850 long tons (860 t) of dangerous material had been removed, with no accidents while working in a temperature of 107 °F (42 °C) in the shade, at a cost that was less than one-half the original estimated £1000.[25][27]

Removal of the sand drift and preservation

[edit]While the Royal Engineers had made efforts to prevent or at least slow the buildup of the great drift of sand in front of the Great Temple the Egyptian Department of Antiquities had for many years been concerned as it was slowly but steadily covering a large part of the façade, and threatening to block the doorway. They also suspected that it might be concealing other structures. Therefore between 1909 and 1910 under the leadership of Alessandro Barsanti they permanently cleared away the sand.[29]

The sand was disposed of down the slope in front of the temples so as to form a wide platform, which was held in place by a retaining wall along the riverbank.[29] The opportunity was also taken to install a flight of steps from the new platform down to the river.

When the drift was removed a row of statues was discovered along the terrace in front of the colossi.[29] These consisted of figures of the Pharaoh and of the sacred hawk of the sun alternating along the entire length. Also a previously unknown small building now known as the Chapel of Re-Harakhty was found.[29][28]

An examination of the colossi found that that they were in a very dangerous condition, which was stabilized by inserting cement into the cracks and cavities. Iron pins were used to hold together the smaller cracks.[29] In addition a numerous repairs were made in the inner halls of the Great Temple.[29]

Since its discovery in 1893 Gaston Maspero the head of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities, had arranged for the grave of Benjamin Tidswell to be maintained once a year. In 1908 it was noticed that the preceding Nile inundation had undermined the grave, and that the next flood would wash it away entirely.[28] Therefore in 1909 the remains were removed and laid in a lead coffin, which was placed in a wooden coffin, and temporary stored in a chamber within the Great Temple. On the 3 January 1910 the remains were permanently interred in the corridor to the south of the façade between the base of the southern most colossus and the rock face with a granite tombstone installed over it.[28]

In the early 1950s the only public transportation to Abu Simbel was the twice-weekly boat that carried passengers and cargo between Aswan and the Sudan.[30]

Relocation

[edit]In 1959, an international donations campaign to save the monuments of Nubia began: the southernmost relics of this ancient civilization were under threat from the rising waters of the Nile that were about to result from the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The resulting lake would raise the water level at Abu Simbel by up to 60 metres (200 ft).[31] Once submerged the water would cause the sandstone from which they were constructed to lose its strength and durability.[31]

A number of schemes were proposed in early 1962 from various institutions and individuals on how to save the temples.

One scheme to save the temples based on an idea by Irish film producer William MacQuitty was to leave them where they were and building a dam around them, containing crystal-clear filtered water kept at the same height as the muddy Nile water outside.[32] Visitors would then have looked at the engulfed temples from curved observation galleries on three levels.[33] He envisaged that in time the dam would be outdated by atomic power and the water level lowered, restoring the temples to their original state. As they considered that raising the temples ignored the effect of erosion of the sandstone by desert winds the idea was taken up and turned into a proposal by architects Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, working with civil engineer Ove Arup.[34] Unfortunately as sandstone is porous the water would eventually cause the temples to crumble.

Another scheme proposed by an American construction executive was to construct concrete barges under the temples and then allow the rising lake water to raise them.[33]

Short listed proposals

[edit]Eventually two proposals were identified as being technical feasible. One from André Coyne and Jean Bellier, from the French engineering firm of Coyne et Bellier (now Tractebel Engineering) was for the temples to remain in position, protected by a curved 240 feet (73 m) high thin-walled concrete dam with a reflecting pool in front of the temples. Visitors would arrive by boat and disembark at the top of the dam. Pumps would be required to permanently manage the seepage of water from the lake through the dam.[33] This idea was dismissed due to the risks of the extensive drainage system failing but also due to its expected due to an estimated cost of $82 million),[35] high ongoing operating costs and the believe that temples would slowly be damaged by damp arising from capillary attraction.[36] The second was from the Italian firm of Italconsult, following an idea by Pierre Gassola. They proposed cutting away the top of the cliff above the temples, before cutting behind them to sever them from the cliff.[36] A reinforced concrete platform would then be inserted under them and after enclosing each in a massive concrete box they would then be raised on hydraulic jacks up 200 feet (61 m) to a higher location.[33] The Great Temple was estimated to weigh 250,000 tons while the combined estimated weight of the Small Temple and its concrete box was 100,000 tons.[33] No structure of this weight had ever been lifted before,[37] and as well as its significant cost it would take three years before it would be possible to actually commence raising the temples, despite the reservoir was expected to begin being raised in the autumn of 1964. This proposal was estimated to cost $62 million.[35] Despite this UNESCO announced on 10 June 1962 that it was their preferred option and commissioned the Swedish engineering consulting firm Vattenbyggnadsbyrån (VBB) to oversee the project.[33]

VBB's proposal

[edit]While attempts were being made to raise the funds need to undertaken the project the Egyptian Minister of Culture Tharwat Okasha had secretly commissioned VBB to investigate a possible backup to the French and Italian proposals. After solving various problems VBB proposed disassembling the temples into blocks as large as possible and lifting them up to a higher location and reassembling them. There were concerns however that as sandstone is made of grains of quartz that are weakly connected any cutting and lifting would lead to cracking and breaking of blocks with the possibly of up to a third being ruined.[38] By early June 1963 Egypt had adopted the VBB proposal as not only had it a realistic chance of being able to save the temples before they were flooded but was estimated to cost US$36 million, half the cost of the other proposals.[38] Max McCullough a special assistant for educational and cultural affairs in the State Department, who was the American representative on the UNESCO committee stated, "This means that for the first time we have a plan acceptable to everybody and, secondly that we are within striking distance of the money required for the project."[39]

By 14 June 1963 agreement had been also been reached on how to finance the work.[39] Egypt would contribute $11.5 million, 43 UNESCO member states another $7.7 million with United States in addition intending to fund up to a third of estimated cost.[39] It was hoped that private contributions would make up the reaming amount. Prior to committing to its contribution the United States had canvased 11 engineers, archaeologists and Egyptologists, who all supported VBB’s proposal.[39] Two weeks later the government of Egypt invited bids from firms wishing to work on the project to be submitted by 15 September 1963. At the time it was expected that approximately 40 companies would submit bids.[39] The publicity about the potential loss of the temples had by this time increased the number of visitors over the previous three years from approximately 50 a year to as many as 150 a day.[39]

Assembling of the project team

[edit]Having already successfully relocated the Temple of Kalabsha the German construction company Hochrief,[40] was appointed to lead the team of contractors, which was called “Joint Venture Abu Simbel” (JVAS). Walter Jurecha was appointed project manager, with Carl Theodar Mackel in charge of site activities.[38] Joining Hochrief in the joint venture were the Egyptian firm Atlas, the French construction company Grands Travaux de Marseille, the Italian civil construction company Impresit-Girola-Lodigiani (Impregilo) and from Sweden Skånska cementgjuteriet (Skanska) and Svenska Entreprenad AB (Sentab). The evolvement of Swedish companies in JVAS led to orders being given to Atlas Copco (to supply pneumatic powered drilling equipment) and Sandvik AB (to develop and manufacture the required saws).[41][42] VBB led by Karl Fredrick Ward (as the project’s head engineer) was retained as the project’s consulting engineers and architects.[43] Their involvement was to last for approximately 10 years.

The actual cutting and a reassembly of the temples was entrusted to the Impreglio, who intended to employ marmisti (stone cutters) who had learnt their trade cutting marble in the Carrara quarries to undertake the actual cutting.[38] Two international committees containing archaeologists, architects and engineers provided technical advice to the joint venture, while the Egyptian government interests was represented on site by their own resident engineer who was supported by archaeologists from the Department of Antiquities. By the spring of 1964 approximately 1,000 people were being employed by the project at Abu Simbel.[38] For the first year of the project they lived in houseboats, tents and huts until by 1965 a proper construction village could be established, complete with a mosque, cafeteria, cinema, sports facilities and a swimming pool. As there was no school, children were taught by correspondence. Supplies and equipment from Cairo took four to six weeks to reach the site, while it took five months from Europe.[38]

Construction of a temporary cofferdam

[edit]Based on the proposed construction schedule for the Aswan Dam it was necessary for the temples to be removed from their existing location by 15 August 1966 if they were not to be inundated by the raising lake level.[38] As it was expected that by the winter of 1964 that the lake level would be 16 feet (4.9 m) higher than the base of the Small Temple and 4 feet (1.2 m) higher than the base of the Great Temple.[38] As a result not all of the contracts being signed the first task was in November 1963 to commence constructing a 82 feet (25 m)[38] high temporary cofferdam formed around steel sheets that were filled with earth from both sides.[44] This material was sourced from the excavations above behind the temples. Work continued in three 12-hour shifts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week until the 370 metres (1,210 ft)[44] long dam was finished and it then had to be increased in height to 27 metres (89 ft)[44] when higher floodwaters in 1964 than expected threatened to overtop it. Water seeping through the dam forced the installation of three drainage tunnels connected to a pumping station which used 25 pumps to remove 750,000 US gal (2,800,000 L) of water an hour.[38][45] it was then found that water was seeping up via the soil under the cofferdam. To prevent it reaching the temples, drilling rigs were bought in to drill 15 deep wells in each of which an underwater pump was installed to remove any seepage.[45]

Cutting free the temples

[edit]In parallel with the creation of the cofferdam initial work at the temples themselves began with removing any loose rocks from between the two temples and deposited 5,000 truckloads of sand[46] totalling 34,000 short tons (31,000 t)[45] in front of their facades in protect them from any falling stones during the removal of the cliff face above them. The sand reached as high as the bottom of the uppermost frieze, which was itself protected by the construction of a temporary structure overtop of it. Steel tunnels were installed through the sand to allow workers to access the interior chambers of the temples. Inside they installed scaffolding to support the ceilings and walls, during removal of the cliff above them. Initially excavators were used to removal the cliff from the uppermost 190 feet (58 m) of the cliff, before with the risk of damage from vibrations increasing pneumatic hammers were used to remove the remaining 60,000 short tons (54,000 t)[45] to within 2.5 feet (0.76 m) of the ceiling and walls.[46] In total approximately 300,000 tons of rock were removed to free the temples from the cliff.[46]

To assist in assessing where to make the required cuts the project team had the use of detailed drawings of the facades of the two temples which had prepared in 1959 by French National Geographic Institute.[31] The cuts were intended to be only 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) wide which will assist in ensuring that they would be as close to invisible as possible once the temples were reassembled. After numerous tests to determine the best means of holding the delicate sandstone of the blocks together Egyptian workers spent seven months injecting the surface indentations and cracks of the interiors and facades with a epoxy resin.[46] Tests had already been conducted with various types of powered and manual saws to determine the best way of cutting the stone. With a few exceptions it was determined that only handsaws would be employed on the facades and interiors. The most common types used were Novello saws (which had diamond -tipped teeth) and helicoidal saws. Once the sandstone had been strengthened with epoxy, work commenced on reducing the stresses that would occur when the rock above the temple’s ceilings was removed. This was accomplished by using chain saws to insert approximately 3.5 feet (1.1 m) deep cuts inside the temples at the junction of the ceilings and walls.[46] At the same time work commenced using handsaws to cut grooves as thin as possible into the ceiling, which was supported by felt tipped steel scaffolding. Rubber sheets were installed to protect the decoration while the cutting was undertaken.[44] The activities inside the cramped dust filled temples required the Italian stonecutters to work in temperatures of 100 °F (38 °C) and higher.[46] The Joint Venture’s contract specified that that the weight of the individual blocks was not to exceed 20 tons for the temple chambers and 30 tons for the facades. To meet this requirement and to minimise the impact of any cuts considerable amount of work had gone into selecting where the cuts were to made but as they undertook the cutting the stonecutters would often use their innate feeling for stone to deviate. Once the cuts had been completed steel pins where inserted via holes drilled in the cuts to allow the workers on the exterior to other side of the stone to determine where to make the cuts that would join with the interior cuts. As they would not be seen these exterior cuts were wider as they were made with power saws.

Holes were drilled in the separated blocks and steel lifting pins were inserted and epoxied in place on each block with which to lift each block. To further protect the blocks from cracking each was coated with a protective coating. Any blocks with decorated interior were wrapped in linen. After nine months of continuous work by 500 workers the first block was lifted out on 21 May 1965.[46] To lift the blocks two guy-rope derricks were installed at each temple, one with 20 ton and the other a 30 ton lifting capacity.[47] Each block was given a unique identification code (which identified its exact position) and carefully transported on a sand cushion in a slow-moving trailer to one of two temporary holding areas with a total area of 44,000 square metres (470,000 sq ft).[47] By the time of the first block's removal 3,000 people[48] were living in the construction village, of whom 1,850 were working on site.[40] As work progressed on extracting the interiors, the sand was removed from the front of the facades. As the heads of figures of the pharaohs on the front of the Great Temple exceeded the 30-ton lifting limit, the weight was reduced by cutting their crown off and removing them. Then on 15 October, the most experienced stone cutters commenced cutting the first face away from behind their ears.[48] After this was completed, on the next day the first 19-ton face was removed by the crane. To protect them from sandstorms during storage, each block was covered in straw mats, and if necessary given additional applications of resin.

On 16 April 1966, two weeks ahead of schedule and six months after the disassembly had commenced the last block was removed, with none having been seriously damaged.[48] In total the temples were cut into 1,036 blocks.[35] Some of the rock and sand used to construct the cofferdam was removed for reuse in creating the new cliff behind the relocated temples, before the rest of the dam was pushed into the rising waters of the lake in late August 1966. The smallest individual block weighed seven tons.[49]

Reassembling the temples

[edit]

Meanwhile in January 1966,[48] work had commenced on constructing the foundations for the relocated temples: 208 m (682 ft) further inland and vertically 65 m (213 ft) higher for the Great Temple, and 67 m (220 ft) for the Small Temple.[31] The temples were oriented at the new location to duplicate the two occasions each year that the rising sun penetrated the innermost sanctum at the rear of the Great Temple. To ensure the correct orientation, the permitted deviation when reassembling the Great Temple was plus or minus 5 mm.[42] The inner walls and ceilings of the temple were reassembled first. The interior joints were filled in by specialists from the Department of Antiquities, using a sand paste mixed to match the existing colours; while the wider cuts at the rear were filled in with a cement-based mortar.

The facade of the temples were then reassembled, with the first face of the 67 feet (20 m) high statues pharaoh Ramses on the Great Temple reunited with its body on 14 September 1966.[48] By the end of 1966, the reassembly of the 235 blocks[49][44] making up the Small Temple was completed; and six weeks later, the reassembly of the 807 blocks[49][44] making up the Great Temple.[48] Once this was done, to ensure that there was no weight on the temple interiors and to reduce the amount of backfilling required, a reinforced protective dome was constructed by Hünnebeck GmbH over the rear of each temple. The dome for the Great Temple had a span of 55 metres (180 ft) and a height of 19 metres (62 ft), with a loading of 20 tons per square metre at the apex.[47] To construct this dome, 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) SL 15 girders were installed to support the formwork for the concrete. The dome for the Small Temple had a span of 21 metres (69 ft) and a height of 6.6 metres (22 ft).[47]

Over top of these domes, an artificial hill was constructed using 300,000 tons of material removed from the original site to recreate a close approximation of the original setting.[50] Prior to the project, visitors had to bring their own lamps with them to inspect the interiors of the temples. As it was expected that visitor numbers would increase, permanent electric lighting and a mechanical ventilation system hidden in the domes were installed, both for the comfort of visitors and to protect the interior decoration from the effects of temperature and humidity.

On 22 February 1966, members of the team gathered at sunrise to confirm that the statues of Rameses, Amun and Ra-Horakhty housed 63.1 metres[44] inside the innermost sanctum of the Great Temple were illuminated by the sun’s rays, while that of Ptah was not. A further check was made on the other significant date, 22 October.

Completion

[edit]By the early summer of 1968 the project was completed, 18 months ahead of schedule.[48]

On 22 September 1968, 500 people attended the official inauguration of the relocated complex. Prominent among the guests were the Egyptian Minister of Culture Tharwat Okasha, Egyptologist and leading preservation advocate Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, UNESCO Director-General René Maheu, and Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, who was a significant fundraiser.[51][52] At the time, the relocation was considered one of the greatest challenges of archaeological engineering in history.[53] The success of the relocation of Abu Simbel helped the United Nations to introduce a convention establishing the UNESCO World Heritage List.[54]

The project had cost $41.7 million or 18.5 million Egyptian pounds (equivalent to $425.81 million in 2024), of which half was borne by Egypt and half provided by international contributions from 48 countries.[35] This was approximately 10% higher than the VBB's original estimate.[31]

Today, hundreds of tourists visit the temples daily. Most visitors arrive by road from Aswan, the nearest city. Others arrive by plane at Abu Simbel Airport, an airfield specially constructed to serve the temple complex, with year-round flights to nearby Aswan International Airport and limited seasonal flights to Cairo International Airport.

Description

[edit]The complex consists of two temples. The larger one is dedicated to Ra-Horakhty, Ptah and Amun, Egypt's three state deities of the time, and features four large statues of Ramesses II in the facade. The smaller temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, personified by Nefertari, Ramesses's most beloved of his many wives.[55] The temple is now open to the public.

Great Temple

[edit]

The Great Temple at Abu Simbel, which took about twenty years to build, was completed around year 24 of the reign of Ramesses the Great (which corresponds to 1265 BC). It was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, as well as to the deified Ramesses himself.[56] It is generally considered the grandest and most beautiful of the temples commissioned during the reign of Ramesses II, and one of the most beautiful in Egypt.

Entrance

[edit]

The single entrance is flanked by four colossal, 20 m (66 ft) statues, each representing Ramesses II seated on a throne and wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. The statue to the immediate left of the entrance was damaged in an earthquake, causing the head and torso to fall away; these fallen pieces were not restored to the statue during the relocation but placed at the statue's feet in the positions originally found.

Next to Ramesses's legs are a number of other, smaller statues, none higher than the knees of the pharaoh, depicting: his chief wife, Nefertari Meritmut; his queen mother Mut-Tuy; his first two sons, Amun-her-khepeshef and Ramesses B; and his first six daughters: Bintanath, Baketmut, Nefertari, Meritamen, Nebettawy and Isetnofret.[56]

The façade behind the colossi is 33 m (108 ft) high and 38 m (125 ft) wide. It carries a frieze depicting twenty-two baboons worshipping the rising sun with upraised arms and a stele recording the marriage of Ramesses to a daughter of king Ḫattušili III, which sealed the peace between Egypt and the Hittites.[57]

The entrance doorway itself is surmounted by bas-relief images of the king worshipping the falcon-headed Ra Horakhty, whose statue stands in a large niche.[56] Ra holds the hieroglyph user and a feather in his right hand, with Maat (the goddess of truth and justice) in his left; this is a cryptogram for Ramesses II's throne name, User-Maat-Re.

Interior

[edit]The inner part of the temple has the same triangular layout that most ancient Egyptian temples follow, with rooms decreasing in size from the entrance to the sanctuary. The temple is complex in structure and quite unusual because of its many side chambers. The hypostyle hall (sometimes also called a pronaos) is 18 m (59 ft) long and 16.7 m (55 ft) wide and is supported by eight huge Osirid pillars depicting the deified Ramesses linked to the god Osiris, the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life and vegetation, to indicate the everlasting nature of the pharaoh. The colossal statues along the left-hand wall bear the white crown of Upper Egypt, while those on the opposite side are wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt (pschent).[56] The bas-reliefs on the walls of the pronaos depict battle scenes in the military campaigns that Ramesses waged. Much of the sculpture is given to the Battle of Kadesh, on the Orontes river in present-day Syria, in which the Egyptian king fought against the Hittites.[57] The most famous relief shows the king on his chariot shooting arrows against his fleeing enemies, who are being taken prisoner.[57] Other scenes show Egyptian victories in Libya and Nubia.[56]

From the hypostyle hall, one enters the second pillared hall, which has four pillars decorated with beautiful scenes of offerings to the gods. There are depictions of Ramesses and Nefertari with the sacred boats of Amun and Ra-Horakhty. This hall gives access to a transverse vestibule, in the middle of which is the entrance to the sanctuary. Here, on a black wall, are rock cut sculptures of four seated figures: Ra-Horakhty, the deified king Ramesses, and the gods Amun Ra and Ptah. Ra-Horakhty, Amun Ra and Ptah were the main divinities in that period and their cult centers were at Heliopolis, Thebes and Memphis respectively.[56]

Solar alignment

[edit]

It is believed that the axis of the temple was positioned by the ancient Egyptian architects in such a way that on October 22 and February 22, the rays of the sun would penetrate the sanctuary and illuminate the sculptures on the back wall, except for the statue of Ptah, a god connected with the realm of the dead, who always remained in the dark. People gather at Abu Simbel on these days to witness this.[56][57][clarification needed]

These dates are allegedly the king's birthday and coronation day, respectively. There is no direct evidence to support this. It is logical to assume, however, that these dates had some relation to a significant event.[citation needed] In fact, according to calculations made on the basis of the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (Sothis) and inscriptions found by archaeologists, this date must have been October 22. This image of the king was enhanced and revitalized by the energy of the solar star, and the deified Ramesses the Great could take his place next to Amun-Ra and Ra-Horakhty.[56]

Because of the accumulated drift of the Tropic of Cancer due to Earth's axial precession over the past 3 millennia, the event's date must have been different when the temple was built.[58] This is compounded by the fact that the temple was relocated from its original setting, so the current alignment may not be as precise as the original one.

The phenomenon was first reported by Amelia Edwards in 1874:

It is fine to see the sunrise on the front of the great temple; but something still finer takes place on certain mornings of the year, in the very heart of the mountain. As the sun comes up above the eastern hill-tops, one long, level, beam strikes through the doorway, pierces the inner darkness like an arrow, penetrates to the sanctuary and falls like fire from heaven upon the altar at the feet of the gods. No one who has watched for the coming of that shaft of sunlight can doubt that it was a calculated effect and that the excavation was directed at one especial angle in order to produce it. In this way Ra, to whom the temple was dedicated, may be said to have entered in daily and by a direct manifestation of his presence to have approved the sacrifices of his worshipers.[59]

Greek graffito

[edit]A graffito inscribed in Greek on the left leg of the colossus seated statue of Ramesses II, on the south side of the entrance to the temple records that:

When King Psammetichus (i.e., Psamtik II) came to Elephantine, this was written by those who sailed with Psammetichus the son of Theocles, and they came beyond Kerkis as far as the river permits. Those who spoke foreign tongues (Greek and Carians who also scratched their names on the monument) were led by Potasimto, the Egyptians by Amasis.[60]

Kerkis was located near the Fifth Cataract of the Nile "which stood well within the Cushite Kingdom."[61]

Small Temple

[edit]

The temple of Hathor and Nefertari, also known as the Small Temple, was built about 100 m (330 ft) northeast of the temple of Ramesses II and was dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Ramesses II's chief consort, Nefertari. This was in fact the second time in ancient Egyptian history that a temple was dedicated to a queen. The first time, Akhenaten dedicated a temple to his great royal wife, Nefertiti.[56] The rock-cut facade is decorated with two groups of colossi that are separated by the large gateway. The statues, slightly more than 10 m (33 ft) high, are of the king and his queen. On either side of the portal are two statues of the king, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt (south colossus) and the double crown (north colossus); these are flanked by statues of the queen.

Remarkably, this is one of very few instances in Egyptian art where the statues of the king and his consort have equal size.[56] Traditionally, the statues of the queens stood next to those of the pharaoh, but were never taller than his knees. Ramesses went to Abu Simbel with his wife in the 24th year of his reign. As the Great Temple of the king, there are small statues of princes and princesses next to their parents. In this case they are positioned symmetrically: on the south side (at left as one faces the gateway) are, from left to right, princes Meryatum and Meryre, princesses Meritamen and Henuttawy, and princes Pareherwenemef and Amun-her-khepeshef, while on the north side the same figures are in reverse order. The plan of the Small Temple is a simplified version of that of the Great Temple.

As in the larger temple dedicated to the king, the hypostyle hall in the smaller temple is supported by six pillars; in this case, however, they are not Osiris pillars depicting the king, but are decorated with scenes with the queen playing the sistrum (an instrument sacred to the goddess Hathor), together with the gods Horus, Khnum, Khonsu, and Thoth, and the goddesses Hathor, Isis, Maat, Mut of Asher, Satis and Taweret; in one scene Ramesses is presenting flowers or burning incense.[56] The capitals of the pillars bear the face of the goddess Hathor; this type of column is known as Hathoric. The bas-reliefs in the pillared hall illustrate the deification of the king, the destruction of his enemies in the north and south (in these scenes the king is accompanied by his wife), and the queen making offerings to the goddesses Hathor and Mut.[57] The hypostyle hall is followed by a vestibule, access to which is given by three large doors. On the south and the north walls of this chamber there are two graceful and poetic bas-reliefs of the king and his consort presenting papyrus plants to Hathor, who is depicted as a cow on a boat sailing in a thicket of papyri. On the west wall, Ramesses II and Nefertari are depicted making offerings to the god Horus and the divinities of the Cataracts—Satis, Anubis and Khnum.

The rock-cut sanctuary and the two side chambers are connected to the transverse vestibule and are aligned with the axis of the temple. The bas-reliefs on the side walls of the small sanctuary represent scenes of offerings to various gods made either by the pharaoh or the queen.[56] On the back wall, which lies to the west along the axis of the temple, there is a niche in which Hathor, as a divine cow, seems to be coming out of the mountain: the goddess is depicted as the Mistress of the temple dedicated to her and to queen Nefertari, who is intimately linked to the goddess.[56]

Climate

[edit]Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as hot desert (BWh).

| Climate data for Abu Simbel | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

26 (79) |

30.2 (86.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

39.1 (102.4) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

40.2 (104.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

36 (97) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

33.7 (92.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27 (81) |

31 (88) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

28.8 (83.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23 (73) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

18.7 (65.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Average rainy days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org[62] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather to Travel[63] for sunshine and rainy days | |||||||||||||

In popular culture

[edit]The temples appear in the 1978 film Death on the Nile based on the book of the same name by Agatha Christie. The temples also appear in the 2001 film The Mummy Returns as part of the road to Ahm-Shere.

Gallery

[edit]Historic pictures

[edit]- Temple of Ramesses II

-

The façade of the Great Temple in 1854 by John Beasley Greene

-

Abu Simbel between 1905 and 1907

-

Genevese architect Jean Jacquet, a UNESCO expert, makes an architectural survey of the Great Temple of Rameses II

-

Front view of the Great Temple before 1923

-

Interior of the Great Temple, before cleaning

-

Interior of the Great Temple, after cleaning

-

People standing at the entrance to the Great Temple, sometime before 1923

-

View of the Great Temple from the west, photo credited to William Henry Goodyear, before 1923

-

Facade of the Great Temple from before 1923

-

View of the rightmost statue at the Great Temple, partially excavated, with a person (possibly William Henry Goodyear) for scale

-

View of the Great Temple's colossal statues from the right, partially excavated

-

Colour photo of the Great Temple from the right, partially excavated, from before 1923

-

The Great Temple from the right, from before 1923

- Temple of Nefertari

-

Earliest photo of Small Temple, 1854 by John Beasley Greene

-

Stele adjacent to Small Temple, 1854 by John Beasley Greene

-

The Small Temple from below and left, before 1923

-

Interior of Nefertari's (queen's) temple at Abu Simbel, with graffiti

-

The Small Temple in context, before relocation. Goodyear Brooklyn Museum Archives

Modern pictures

[edit]- Temple of Ramesses II

-

Aerial view of Abu Simbel in September 2004

-

Facade of the Temple of Ramesses II, photo taken in 2007

-

Close-up of the leftmost statue at the temple of Rameses II

-

Central, inset statue of Ra-Horakhty at the Great Temple

-

The carvings of baboons on the cornice above the heads of the statues of Ramesses at the Great Temple

-

A close-up of one of the colossal statues of Ramesses II wearing the double crown of Lower and Upper Egypt

-

Frieze inside the Great Temple of Abu Simbel

- Temple of Nefertari

-

Closer view of the Small Temple, 2007

-

Ramesses offering to seated god Ptah. Frieze inside the Small Temple.

See also

[edit]- Cave temples in Asia

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

- List of archaeoastronomical sites sorted by country

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

References

[edit]- ^ "Abu Simbel". pcma.uw.edu.pl. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ a b Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2013). Temple of the Word: Sanctuaries, Cults and Mysteries of Ancient Egypt (Hardcover). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774165634.

- ^ a b Hawass, Zahi (2001). The Mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Sun. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-623-3.

- ^ Burckhardt, John Lewis (1819). Travels in Nubia. London: John Murray. pp. 88–9. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2020). A World Beneath the Sands: Adventurers and Archaeologists in the Golden Age of Egyptology (Hardcover). London: Picador. pp. 96. 97, 239, 240, 336. ISBN 978-1-5098-5870-5.

- ^ Belzoni, ‘‘Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries…’’, p. 132

- ^ Bickerstaffe, Dylan (12 December 2023). "The rescue of Abu Simbel: A history of restoration, exploration, and resurrection". The Past. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ^ a b c "Giovanni Battista Belzoni". Ancient Egypt and Archaeology Web Site. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Belzoni, ‘‘Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries…’’, pp. 124

- ^ Belzoni, ‘‘Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries…’’, p. 132

- ^ Lane E, "Descriptions of Egypt," American University in Cairo Press. pp.493-502.

- ^ "The Temple at Dendur, Nubia". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 September 2025.

- ^ "David Roberts, R.A. (1796 - 1864)". Ancient Egypt and Archaeology Web Site. Retrieved 20 September 2025.

- ^ a b Viscount Castlereagh, Robert Stewart (1847). Journey to Damascus through Egypt, Nubia, Arabia Petraea, Palestine and Syria (Hardcover). Vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn. pp. 88, 96–99.

- ^ Romer, Isabella Frances (1846). A Pilgrimage to the Temples and Tombs of Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine, in 1845-6 (Hardcover). Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 204–214.

- ^ Flaubert, Gustave (1996). Flaubert in Egypt: A Sensibility on Tour (Softcover). Translated by Steegmuller, Francis. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140435824.

- ^ a b McCauley, Anne (1982). "The Photographic Adventure of Maxime Du Camp". In Oliphant, Dave; Zigal, Thomas (eds.). Perspectives on Photography. Austin: Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. pp. 19–51. ISBN 9780879590987.

- ^ Lyons, Claire L.; Papadopoulos, John K.; Stewart, Lindsey S.; Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew (2005). Antiquity Photography - Early Views of Ancient Mediterranean Sites (PDF) (Hardcover). Los Angeles: Getty Publications. pp. 9, 11, 39, 94. 95. ISBN 978-0-89236-805-1.

- ^ Chernick, Karen (23 December 2019). "The Writer Who Pioneered Travel Photography". Art & Object. Retrieved 7 October 2025.

- ^ Smith, Moya; Tunmore, Heather (2007). "Imaging Ancient Egypt: Abu Simbel Old and New" (PDF). Western Australian Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2025.

- ^ O'Neill, Patricia (2009). "Destination as Destiny". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 30: 52–53.

- ^ Edwards, ‘‘A Thousand Miles up the Nile’’, p. 284

- ^ Upper Egypt and Nubia as far as the Second Cataract (Hardcover). Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1892. pp. 331–339.

- ^ a b c d e f MLC (August 1993). "Early days" (PDF). The Royal Engineers Journal. 107 (2). The Institution of Royal Engineers: 193.

- ^ a b c d Budge, E. A. Wallis (1906). Cook’s Handbook for Egypt and the Sudan (Hardcover) (2nd ed.). London: T. Cook & Son. pp. 729–733.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Edwards, A. B. D. (September 1967). "The Corps and the Rock Temple at Abu Simbel" (PDF). The Royal Engineers Journal. LXXXI (3). The Institution of Royal Engineers: 256–257.

- ^ a b c d e Budge, E. A. Wallis (1921). Cook’s Handbook for Egypt and the Sudan (Hardcover) (4th ed.). London: Thomas Cook & Son. pp. 530–537.

- ^ a b c d e f "Remarkable Discoveries Made Through Excavations at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel in Egypt, with a Reconstruction of the Temple of Vesta at Rome Founded on Data Provided by Coins", New York Times, New York, 10 December 1911, retrieved 1 October 2025

- ^ Walzspecial, Jay (23 January 1960). "Cairo Seeks Means to Save Temple Above Aswan; Scheduled Flooding of Nile May Erase Art of Pharaoh". New York Times. New York. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Berg, Lennart (1978). "The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples". International Council on Monuments and Sites. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Pioneering director of 'A Night to Remember'". Irish Times. 21 February 2004. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, pp. 219–221

- ^ Fry, Drew, Knight and Creamer, Architecture, 1978, London, Lund Humphries

- ^ a b c d Mohamed, Shehata Adam (March 1980), "Victory in Nubia: Egypt", UNESCO Courier: 5–15

- ^ a b Vattenbyggnadsbyrån, ‘‘The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples: Concluding Report’’, p. 24

- ^ Vattenbyggnadsbyrån, ‘‘The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples: Concluding Report’’, p. 28

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, pp. 223, 247-251

- ^ a b c d e f Grose, Peter (16 June 1963), "HOPES OF SAVING ABU SIMBEL GAIN; U.A.R. to Invite Bids Soon for Work on Temples Swedish Plan Approved", New York Times, New York, retrieved 18 September 2025

- ^ a b Vattenbyggnadsbyrån, ‘‘The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples: Concluding Report’’, p. 31

- ^ "Egypt and Sweden celebrate 50th anniversary of joint rescue of Abu Simbel temples". Sweden Aboard. 21 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ a b Copco, Atlas. "Abu Simbel – Unparalleled relocation project". Atlas Copco. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, pp. 250, 257

- ^ a b c d e f g Ibrahim, Medhat Abdul Rahman (22 February 2018). "Saving Abu Simbel: 50 Years On". Egypt Today. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d de Carvalho, George (2 December 1966), "The Sun Rises as Pharaoh Planned", Life, vol. 61, no. 23, pp. 38–39

- ^ a b c d e f g Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, pp. 253-258

- ^ a b c d Pallini, Cristina; Scaccabarozzi, Annalisa (2012). "Imagination, design, technique: Three European projects for Abu Simbel". In Piaton, Claudine; Godoli, Ezio; Peyceré, David (eds.). Building Beyond The Mediterranean: Studying The Archives of European Businesses (1860-1970). Arles: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art. pp. 184–195. doi:10.4000/books.inha.12774. ISBN 9791097315016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, pp. 259-258

- ^ a b c "A salvage operation that inspired the world: Abu Simbel and the World Heritage". Sarat. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Vattenbyggnadsbyrån, ‘‘The Salvage of the Abu Simbel Temples: Concluding Report’’, p. 125

- ^ Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, p. 268

- ^ Abu Simbel: Addresses delivered at the ceremony to mark the completion of the operations for saving the two temples, UNESCO, 22 September 1968

- ^ Spencer, Terence (2 December 1966), "The Race to Save Abu Simbel Is Won", Life, vol. 61, no. 23, pp. 32–37

- ^ Olson, ‘‘Empress of the Nile’’, p. 275

- ^ Fitzgerald, Stephanie (2008). Ramses II: Egyptian Pharaoh, Warrior and Builder. New York: Compass Point Books. ISBN 978-0-7565-3836-1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Alberto Siliotti, Egypt: temples, people, gods,1994

- ^ a b c d e Ania Skliar, Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten, 2005

- ^ "NASA Space Math Abu Simbel Alignment problem with answers" (PDF).

- ^ Edwards, ‘‘A Thousand Miles up the Nile’’, pp. 303, 304

- ^ "king Psammetichus II (Psamtik II)". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ Britannica, p.756

- ^ "Climate: Abu Sinbil – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ "Abu Simbel Climate and Weather Averages, Egypt". Weather to Travel. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Abd el Hamied Ebrahim, Hossam Elden Aboud (2025). "Publication and study of the scenes and texts of the western wall of the chapel of Thoth at the Temple of Abu Simbel". Journal of Aswan Faculty of Arts. 18 (2). Aswan Faculty of Arts: 188–207. doi:10.21608/mkasu.2024.337530.1401.

- Allais, Lucia (2013). "Integrities: The Salvage of Abu Simbel" (PDF). Grey Room (50). Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: MIT Press: 7–45.

- Bankes, William John, ed. (1830). Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Giovanni Finati (Hardcover). Vol. 2. London: John Murray. pp. 193–208.

- Belzoni, Giovanni Battista (1822). Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries within the pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations, in Egypt and Nubia; and of a journey to the coast of the Red Sea, in search of the ancient Berenice; and another to the oasis of Jupiter Ammon (Hardcover) (2nd ed.). London: John Murray.

- De Simone, Maria Costanza, ed. (2024). Remembering the Nubia Campaign. Recollections and Evaluations of the 'International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia' After Fifty Years (Hardcover). Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 141. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-71393-2.

- Edwards, Amelia (1890). A Thousand Miles up the Nile (Hardcover) (2nd ed.). London: George Routledge and Sons. pp. 284–310, 325–353.

- Fernández-Toribio, Salomé Zurinaga (2013). "Rescue Archaeology and Spanish Journalism: The Abu Simbel Operation" (PDF). AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology. 3. Spain: JAS Arqueología S.L.U.: 46–73. doi:10.23914/ap.v3i0.29.

- Howe, Kathleen Stewart (1994). Excursions along the Nile: The Photographic Discovery of Ancient Egypt (Hardcover). Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Museum of Art. ISBN 0-89951-088-4.

- Irby, Charles Leonard; Mangles, James (1823). Travels in Egypt and Nubia, Syria, and Asia Minor; during the years 1817 & 1818. London: Printed for Private Distribution by T. White & Co.

- Lindström, Sune; Bygdén, Alf; Waters, Roger (1962). Abu Simbel: Salvage of the temples, landscaping and general layout; architects' views on restoration, landscaping and general plan (Report). Stockholm: Vattenbyggnadsbyrån.

- Luxor, Natasa Zivaljevic; Pasternak, Hartmut (2021). "The 60th anniversary of the Great Temple of Abu Simbel salvage". PROHITECH 2020, 4th International conference on protection of historic construction. Athens, Greece. pp. 1206–1215. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-90788-4_93. ISBN 978-3-030-90787-7. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- Okasha, Sarwat (2010). "Rameses Recrowned: The International Campaign To Preserve The Monuments Of Nubia, 1959-68". In D’Auria, S. (ed.). Offerings to the Discerning Eye. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 38. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 223–244. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004178748.i-362.74. ISBN 9789047441090.

- Olson, Lynne (2023). Empress of the Nile: The Daredevil Archaeologist Who Saved Egypt's Ancient Temples from Destruction (Hardcover). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0525509479.

- Prakash, Tara (2024). "Emotions and the Manifestation of Ancient Egyptian Royal Power: A Consideration of the Twin Stelae at Abu Simbel". Arts. 13 (6). Basel, Switzerland: MDPI: 174. doi:10.3390/arts13060174.

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny (1987). Temples and Tombs of Ancient Nubia: The International Rescue Campaign at Abu Simbel, Philae and Other Sites. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-92-3-102383-5. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- Prakash, Tara (2024). "Emotions and the Manifestation of Ancient Egyptian Royal Power: A Consideration of the Twin Stelae at Abu Simbel". Arts. 13 (6). Basel, Switzerland: MDPI: 174. doi:10.3390/arts13060174.

- Spencer, Terence (2 December 1966), "The Race to Save Abu Simbel Is Won", Life

- "A salvage operation that inspired the world: Abu Simbel and the World Heritage". Sarat. 1 October 2018.

- "Abu Simbel: Now or never", UNESCO Courier: 4–5, October 1961

External links

[edit]- "Abu Simbel archeological site" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Abu Simbel at the website of Egypt State Information Service

- Salvage of Abu Simbel: estimate of cost. The estimate provided to the Egyptian government in 1962.

- of the first stage of the project for saving Abu Simbel

- Financial aspects of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia Paper dated 30 November 1962 from the 12th UNESCO General Conference.

- The World Saves Abu Simbel. A 29 minute long film produced by UNESCO in 1972 on the relocation of Abu Simbel.

- Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae. A short film produced by UNESCO on Abu Simbel.

- Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie: dessins photographiques recueillis pendant les années 1849, 1850 et 1851 accompagnés d'un texte explicative. The digitized images of the photographs taken by Maxime Du Camp of Abu Simbel which are housed in The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs collection of the New York Public Library.